Traditional Housing in England

England’s traditional housing is a rich tapestry of architectural heritage, shaped by centuries of evolution, regional craftsmanship, and cultural influences. From the distinctive black-and-white timber-framed Tudor homes to the honey-hued stone cottages of the Cotswolds, each style embodies the character of its time and place. These homes not only reflect the materials available in their regions but also offer a glimpse into England’s social history, craftsmanship, and enduring aesthetic charm.

1. Architectural Styles of Traditional English Homes

A. Timber-Framed Tudor Houses: An Icon of British Architecture (15th - 17th Century)

Timber-framed Tudor houses represent an iconic architectural style that flourished in England from the late 15th century to the early 17th century. Characterised by their distinctive black-and-white exteriors, exposed wooden beams, and steeply pitched roofs, these buildings remain among the most recognisable and cherished in British architectural history.

The interiors of these houses typically feature exposed wooden beams, with dark-stained timbers contrasting against white plaster to create a striking aesthetic. Large brick chimneys, often adorned with ornate twisted or patterned designs, became prominent architectural elements. Fireplaces were central to Tudor homes, as advancements in chimney construction improved heating efficiency, while large open hearths provided warmth and served as the primary means of cooking.

Wooden floors, usually made from oak planks, were a common feature, while wealthier households often included elaborately crafted spiral wooden staircases. Decorative plaster ceilings and wall tapestries were also popular in affluent Tudor homes, adding both insulation and a sense of grandeur to interior spaces.

Timber-framed Tudor houses can still be found in historic towns such as Shrewsbury, Cheshire, Suffolk, and Stratford-upon-Avon, where they continue to stand as enduring testaments to Britain’s rich architectural heritage.

B. Thatched Cottages: A Quintessential Form of English Rural Architecture (Medieval - 19th Century)

Traditionally inhabited by peasants, farmers, and rural communities from the Middle Ages all the way through to the 19th century, thatched cottages represent one of the most quintessentially English forms of vernacular architecture. Designed with steeply pitched roofs to facilitate efficient rainwater drainage and prevent leaks, these cottages were built to withstand the elements. The thickness of the thatch, which could reach up to 30 centimetres, provided excellent thermal insulation, ensuring homes remained warm in winter and cool in summer. Many thatched roofs also featured decorative ridging, which varied by region and served both an aesthetic and functional purpose.

The primary structural framework of early thatched cottages was constructed from oak or elm beams, valued for their strength and longevity. Walls were traditionally formed using wattle and daub, a technique that involved weaving wooden strips together and coating them with a mixture of clay, mud, and straw. As building methods evolved during the Tudor and Georgian periods, brick and stone gradually replaced timber framing, particularly in wealthier households.

Windows in thatched cottages were typically small and deep-set, designed to minimise heat loss and enhance structural integrity. Mullioned windows, constructed from stone or wood, divided the glass panes, which were traditionally lattice-leaded due to the high cost of glass before the late 17th century. The thickness of the stone or timber-framed walls often resulted in deep window sills, which served both decorative and functional purposes.

Early thatched cottages were centred around a large open hearth, which was essential for heating, cooking, and baking. Initially, smoke was vented through a simple smoke hole in the thatch, but by the 16th century, stone or brick chimneys became more common, significantly improving air quality and heat retention within the home.

To protect wattle and daub from moisture and weathering, many thatched cottages were whitewashed with lime-based plaster, which also provided a degree of pest resistance. In some regions, exposed timber framing was combined with plaster, brick, or flint infill, creating the distinctive half-timbered aesthetic that remains closely associated with traditional English architecture.

Thatched cottages remain an enduring symbol of English rural heritage, admired for their historical significance, aesthetic appeal, and environmental sustainability. Despite their decline following the Industrial Revolution, conservation efforts and heritage listings continue to preserve these charming dwellings, ensuring they remain an integral part of Britain’s architectural landscape.

Types of Thatched Cottages

Medieval Hall Houses (12th–16th Century)

Medieval hall houses, which emerged in England between the 12th and 16th centuries, were among the most common forms of domestic architecture during the medieval period. These buildings were typically timber framed, with wattle and daub or stone infill, and featured steeply pitched roofs designed to withstand the elements.

At the heart of the medieval hall house was the great hall, a large open space that served as the primary living and communal area. This hall was often double height, with an open timber roof supported by exposed beams. A central hearth provided warmth and was used for cooking, with smoke initially escaping through a louvre in the roof before chimneys became more common in the later medieval period.

Rooms were arranged around the great hall, with service quarters such as kitchens and storage areas located at one end and private chambers at the other. In wealthier homes, an upper floor was later added, creating a solar—a private living space for the family. As architectural styles evolved, hall houses were gradually modified with the addition of chimneys, fireplaces, and more defined room divisions, leading to the development of the fully storeyed houses seen in the Tudor and Elizabethan periods.

Many medieval hall houses survive today, particularly in historic towns and rural areas across England. Examples can be found in counties such as Suffolk, Kent, and Herefordshire, where they continue to be admired for their craftsmanship and historical significance.

Yeoman’s Cottages (16th–18th Century)

Yeoman’s cottages, built between the 16th and 18th centuries, represent a significant shift in English rural architecture, reflecting the growing prosperity of yeoman farmers—landowners who occupied a social class between peasants and the gentry. These cottages were more substantial than the simple dwellings of peasants, often constructed from timber framing, brick, or stone, depending on regional availability.

Unlike earlier medieval hall houses, yeoman’s cottages typically featured a more structured floor plan, with defined rooms and separate living spaces. The central hall remained a focal point, but advancements in construction allowed for the inclusion of fireplaces and chimneys, improving warmth and air quality within the home. Many cottages had upper storeys with bedrooms, accessed via wooden staircases, providing greater privacy and comfort for families.

Roofs were commonly thatched in earlier examples, though wealthier owners often used clay tiles or slate as materials became more accessible. Windows were larger than those found in earlier medieval homes, sometimes featuring mullions and leaded glass panes, though glass remained an expensive commodity until the late 17th century.

The interiors of yeoman’s cottages were modest yet practical, with exposed timber beams, wooden floors, and plastered walls. Large open hearths with inglenooks were a central feature in kitchens, serving both cooking and heating purposes. Over time, as agricultural wealth increased, some yeoman’s cottages were expanded or converted into small manor houses, reflecting their owners’ rising social status.

Many yeoman’s cottages survive in England’s rural landscapes, particularly in counties such as Suffolk, Norfolk, and the Cotswolds, where they remain a testament to the country’s agricultural and architectural heritage.

Chocolate Box Cottages - Early 16th – Early 20th century

Chocolate box cottages epitomise the romantic vision of the English countryside, with their quaint, picturesque charm and timeless aesthetic. The term originated in the early 20th century, when these cottages became popular subjects for illustrations on chocolate boxes, evoking a sense of nostalgia and rural tranquillity.

Typically found in historic villages across England, chocolate box cottages are characterised by their steeply pitched thatched roofs, whitewashed or pastel-coloured walls, and exposed timber beams. Many feature casement windows with leaded glass panes, often framed by climbing roses or wisteria, enhancing their storybook appearance. Decorative thatch ridging is a common feature, adding both artistic detail and practical reinforcement to the roof’s structure.

Constructed primarily between the 16th and 18th centuries, these cottages were originally built for rural labourers and farmers. Their interiors were traditionally modest, with low beamed ceilings, inglenook fireplaces, and wooden or flagstone floors. Over time, many have been carefully restored and modernised while preserving their historic character.

Chocolate box cottages remain a highly sought-after property type, admired for their charm, heritage, and association with England’s pastoral landscape. They can be found in regions such as the Cotswolds, Devon, and the Lake District, where they continue to define the timeless beauty of the British countryside.

Tudor Thatched Cottage, 15th – 17th century

Source: https://www.facebook.com/ukabandoned

Tudor thatched cottages represent a harmonious blend of medieval craftsmanship and the evolving architectural styles of the Tudor period (1485–1603). These cottages, often found in rural villages across England, are distinguished by their steeply pitched thatched roofs, exposed timber framing, and whitewashed wattle-and-daub or brick infill.

Thatched roofs, made from straw or reeds, provided excellent insulation, keeping cottages warm in winter and cool in summer. The steep pitch of the roof was essential for effective rainwater drainage, preventing moisture from seeping into the structure. Many roofs also featured decorative thatch ridging, which varied by region and added both aesthetic appeal and reinforcement to the roof’s durability.

The interiors of Tudor thatched cottages were typically modest yet functional. Low ceilings with exposed wooden beams, open hearths with large inglenooks, and simple wooden floors defined the living spaces. The cottages were often centred around a main hall, which served as the communal area for cooking, dining, and socialising. Over time, as construction methods advanced, additional rooms and upper storeys were added, accessed via wooden staircases.

Windows in Tudor thatched cottages were small and deep-set, designed to retain heat and provide structural stability. Mullioned windows, made from wood or stone, divided the glass panes, which were traditionally lattice-leaded due to the high cost of glass. Thick walls, often a combination of timber framing and wattle-and-daub, contributed to the cottage’s rustic yet sturdy construction.

Tudor thatched cottages remain an enduring symbol of England’s rural heritage. Many can still be found in historic regions such as Suffolk, Wiltshire, and the Cotswolds, where they continue to be cherished for their architectural charm and historical significance.

Cotswold Thatched Cottages: Charm in the Heart of England - 16th to 18th centuries

Cotswold thatched cottages are among the most picturesque and recognisable dwellings in the English countryside, renowned for their honey-coloured limestone walls, steeply pitched thatched roofs, and quaint, storybook appeal. Nestled within the rolling hills and historic villages of the Cotswolds, these cottages embody the region’s rich architectural heritage and enduring craftsmanship.

Constructed primarily from locally quarried Cotswold stone, these cottages blend seamlessly with their natural surroundings. The distinctive golden hue of the limestone deepens over time, adding to the character and warmth of the buildings. Thatched roofs, traditionally made from wheat straw or long-stemmed reed, provide excellent insulation and are carefully crafted to withstand the region’s varied climate. Many feature decorative thatch ridging, an artistic touch that reflects local craftsmanship and traditions.

The interiors of Cotswold thatched cottages are often characterised by low, beamed ceilings, inglenook fireplaces, and flagstone or wooden floors. Windows are typically small and deep-set, designed to retain warmth and enhance structural stability. Mullioned stone windows with leaded glass panes are a common feature, adding to the rustic charm of these historic homes.

Originally built for rural workers and smallholders, many of these cottages have been lovingly restored and modernised while preserving their period features. Today, they are highly sought after as idyllic countryside retreats, admired for their historic charm and timeless beauty. Villages such as Bibury, Bourton-on-the-Water, and Chipping Campden remain some of the best places to find these cottages, where they continue to be a defining feature of the Cotswold landscape.

C. Stone Cottages: Enduring Symbols of English Rural Life (16th - 19th Century)

Stone cottages, built between the 16th and 19th centuries, are an enduring feature of the British countryside, particularly in regions where local stone was abundant. These cottages were constructed using limestone, sandstone, or granite, depending on the geological characteristics of the area. Their solid masonry walls provided excellent durability and insulation, making them well-suited to the British climate.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, many stone cottages were built with simple, functional layouts, often consisting of a single storey with a central hearth. Over time, as building techniques advanced and prosperity increased, additional rooms and upper storeys were added, accessed via wooden staircases. By the 18th and 19th centuries, stone cottages had become more refined in design, incorporating symmetrical façades, larger windows, and pitched roofs covered with slate or thatch, depending on regional traditions.

The interiors of stone cottages were typically modest yet practical. Exposed stone walls, wooden beams, flagstone or timber floors, and inglenook fireplaces were common features. Thick stone walls provided excellent insulation, keeping the interiors cool in summer and retaining warmth in winter. Windows were usually small and mullioned, with lattice-leaded glass panes in earlier examples, while later cottages benefited from advancements in glass production, allowing for larger openings.

Many of these cottages were originally built as homes for agricultural workers, miners, and craftsmen, particularly in areas such as the Cotswolds, Yorkshire Dales, Cornwall, and the Lake District, where local stone was readily available. Today, they remain highly desirable properties, admired for their charm, historical significance, and resilience against time.

England’s rich geological diversity has influenced the construction of various types of stone cottages, each reflecting the regional character and traditional building techniques of its location.

Types of Stone Cottages

1. Cotswold Stone Cottages

Source: https://www.cotswoldtoursandexecutivetravel.com

Cotswold stone cottages are among the most iconic and picturesque homes in England, built using the region’s distinctive honey-coloured limestone. This locally quarried stone gives the cottages their characteristic warm tones, which deepen over time, blending harmoniously with the rolling hills and idyllic villages of the Cotswolds.

These cottages typically feature steeply pitched roofs, mullioned windows, and stone chimneys, reflecting the medieval and Tudor architectural influences that shaped the region. Many have stone-tiled roofs, which, like the walls, are made from Cotswold limestone, creating a cohesive and natural aesthetic. Interiors often include exposed timber beams, flagstone floors, and large inglenook fireplaces, adding to their rustic charm and timeless appeal.

Originally built for weavers, farmers, and craftsmen, these cottages remain a cherished part of the Cotswolds’ historic villages, such as Bourton-on-the-Water, Bibury, and Stow-on-the-Wold. Today, they continue to be highly sought after for their beauty, heritage, and seamless integration into England’s rural landscape, preserving a centuries-old tradition of craftsmanship and local materials.

2. Yorkshire Dale Stone Cottages

Yorkshire Dale stone cottages are an enduring feature of the region’s picturesque valleys and rolling hills, built using locally quarried limestone to withstand the harsh northern climate. Their thick, weather-resistant walls provide excellent insulation, making them well-suited for the often cold and windy conditions of the Dales. The distinctive grey limestone gives these cottages a natural, understated charm that blends seamlessly into the surrounding countryside.

Traditionally, these cottages have stone-flagged roofs, deep-set mullioned windows, and sturdy wooden doors, designed to retain warmth and offer protection from the elements. Interiors typically feature low beamed ceilings, stone or wooden floors, and large open fireplaces, creating a cosy and welcoming atmosphere. Many were originally built as homes for farmers and shepherds, reflecting the Dales’ strong agricultural heritage.

Found in historic villages such as Grassington, Malham, and Hawes, Yorkshire Dales stone cottages continue to be a beloved part of the region’s rural character. Their combination of durability, practicality, and rustic charm makes them a sought-after architectural feature, preserving the traditions and craftsmanship of northern England.

3. Cornish Granite Cottages

Source: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk

Cornish granite cottages are a defining feature of Cornwall’s rugged landscapes, built to endure the region’s harsh coastal winds and moorland weather. Constructed from locally quarried granite, these cottages are known for their thick, solid walls, which provide excellent insulation and resilience against the elements. The coarse texture and natural hues of granite give these cottages a distinctive, weathered charm that blends seamlessly into the surrounding countryside.

Typically found in coastal villages, fishing communities, and moorland settlements, Cornish granite cottages often have small, deep-set windows to minimise heat loss and withstand strong winds. Many feature low ceilings, slate or thatched roofs, and large open fireplaces, designed to retain warmth in the often cool and damp climate. The interiors are traditionally simple yet cosy, with exposed wooden beams and stone flag floors contributing to their rustic appeal.

Historically built for miners, fishermen, and farmers, these cottages reflect Cornwall’s rich industrial and maritime heritage. Today, they remain a cherished part of the region’s architectural identity, seen in historic villages such as St Ives, Zennor, and Boscastle, where they continue to be admired for their durability, charm, and connection to Cornwall’s unique landscape.

4. Lake District Slate Cottages

Lake District slate cottages are a distinctive feature of the region’s dramatic landscapes, built using locally quarried blue-grey slate to withstand the area’s frequent rainfall and harsh weather conditions. The natural durability and water-resistant properties of slate make it an ideal building material, giving these cottages their characteristic solid and weatherproof appearance.

These cottages typically have thick stone walls, deep-set windows, and pitched slate roofs, designed to shed heavy rain efficiently. Many feature whitewashed or lime-rendered exteriors, contrasting beautifully with the dark slate, while interiors often include exposed timber beams, flagstone floors, and large fireplaces, creating a warm and inviting atmosphere.

Originally built for farmers, quarry workers, and rural communities, Lake District slate cottages remain an iconic part of the region’s architectural heritage. Found in villages such as Grasmere, Ambleside, and Keswick, they continue to be admired for their rustic charm, historical significance, and seamless integration into the mountainous landscape.

5. Dartmoor Granite Cottages

© Derek Harper, CC BY-SA 2.0

Dartmoor granite cottages are a defining feature of the wild and windswept landscapes of Dartmoor, built to withstand the region’s harsh weather conditions. Constructed from locally quarried granite, these cottages are characterised by their thick, durable walls, which provide excellent insulation and protection against strong winds and heavy rainfall. The robust nature of granite gives these cottages a solid, timeless appearance, blending seamlessly with the rocky terrain.

Traditional Dartmoor cottages often have low ceilings, deep-set windows, and central hearths, designed to retain warmth in the cold upland climate. Many feature thatched or slate roofs, with small chimneys that help regulate heat and prevent downdrafts. The interiors are typically modest yet cosy, with exposed timber beams, flagstone floors, and large open fireplaces that served as the heart of the home.

These cottages were historically occupied by farmers, miners, and moorland dwellers, reflecting the self-sufficient lifestyle of rural Dartmoor communities. Today, they remain an iconic part of Devon’s architectural heritage, valued for their rustic charm, historical significance, and connection to the region’s rugged landscape.

6. Norfolk Flint Cottages

Norfolk flint cottages are a defining architectural feature of Norfolk, Suffolk, and parts of Kent and Sussex, where flint—a naturally occurring, hard, and durable stone—has been used for centuries in construction. These cottages are particularly distinctive for their knapped flint walls, often combined with brick or stone quoins for added structural support and aesthetic contrast.

Flint is abundant in the chalk-rich soils of East Anglia, making it a readily available and durable building material. Norfolk flint cottages typically have steeply pitched thatched or pantile roofs, deep-set casement windows, and sturdy timber doors, reflecting their rural origins. Interiors often feature exposed wooden beams, brick or flagstone floors, and large fireplaces, creating a warm and traditional atmosphere.

Historically built for farmers, fishermen, and rural workers, these cottages remain a cherished part of Norfolk’s heritage. Villages such as Blakeney, Cley-next-the-Sea, and Walsingham showcase fine examples of flint cottages, preserving their timeless charm and historical significance within the region’s unique landscape.

Each type of stone cottage reflects the unique geology and architectural heritage of its region, showcasing the timeless craftsmanship that has shaped England’s rural landscape for centuries.

Building and Renovating

Whether you're considering building a new cottage or renovating an existing one, several online resources provide detailed blueprints and design inspirations such as Houseplans.com who offer a collection of English cottage house plans, showcasing whimsical and storybook designs. Dream Home Source provides a variety of English cottage style house plans, including storybook and fairytale designs and Eplans.com features English cottage floor plans, ranging from small, cozy designs to larger manors with stone exteriors.

When selecting a blueprint, factors such as the size, layout, and specific architectural features that align with your vision are important. It's also essential to ensure that the design complies with local building regulations and suits the specific characteristics of your site. For personalized guidance, consulting with an architect experienced in English cottage designs is invaluable. They can help tailor a plan to meet your needs while adhering to local building codes and regulations.

By exploring these resources and seeking professional advice, you can find or create a blueprint that captures the essence of an English cottage, blending traditional charm with modern functionality.

Renovating a traditional cottage in Shropshire involves navigating various regulations and guidelines to preserve the architectural and historical integrity of the building.

1. Listed Building Consent: If your cottage is a listed building, any alterations that affect its character, fabric, or appearance require listed building consent from Shropshire Council. This process is separate from standard planning permission and typically takes about eight weeks. It's highly advisable to consult with the council's conservation officers before commencing any work.

2. Building Regulations Compliance: All renovation work must comply with the Building Regulations as amended, who set minimum standards for construction, including aspects like structural integrity, fire safety, and energy efficiency. Even if planning permission isn't required, adherence to these regulations is mandatory.

3. Use of Traditional Materials: The use of traditional materials is often encouraged to maintain the building's historical character. For instance, sourcing local materials such as bricks, tiles, or stone can be beneficial. Employing local craftsmen skilled in traditional building techniques can also enhance the authenticity of the renovation.

4. Conservation Principles: When renovating, aim to retain as much of the original material as possible. Repairs should be prioritized over replacements, and any new additions should be sympathetic to the building's character. For example, if you're repairing stone walls, using stone that matches the original in colour, texture, and size is recommended.

5. Energy Efficiency and Sustainability: Improving energy efficiency in historic buildings should be approached carefully to avoid compromising their character. Options like installing insulation, heat pumps, or renewable energy sources can be considered, but it's essential to seek advice to ensure these modifications are appropriate for traditional structures.

6. Pre-Application Engagement: Engaging with conservation officers before submitting applications can provide valuable insights and increase the likelihood of approval. They can offer guidance on appropriate alterations and extensions, ensuring that your renovation plans align with preservation standards.

By adhering to these guidelines and collaborating with local authorities and experts, you can successfully renovate your Shropshire cottage while preserving its historical significance.

Stone Walls in England: History, Types, and Regulations

Stone walls are an enduring symbol of the English countryside, weaving through fields and villages with a history stretching back centuries. Built from locally sourced stone, they serve as boundaries, agricultural enclosures, and structural foundations for traditional buildings. Beyond their practicality, these walls reflect regional craftsmanship, historical land use, and England’s rural heritage, standing as a testament to the skill and resilience of past generations.

1. Types of Stone Walls in England

Different regions in England have their own distinct styles of stone walls, depending on the locally available materials:

Dry Stone Walls: Traditional Craftsmanship Without Mortar

Volunteers using a 'through stone' to repair a dry stone wall on the estate at Lyme, Cheshire

© National Trust Images/Arnhel de Serra

Dry-stone walls are masonry structures built without mortar, relying on careful stone placement, weight, and friction for stability. They are one of the oldest construction techniques, found in rural, agricultural, and defensive structures worldwide. Common in Yorkshire, the Cotswolds, the Lake District, and the Peak District. It is built primarily for agricultural enclosures and property boundaries.

Types of Dry-Stone Walls

1. Single-Skin Wall

Source: Dave Purvis, Galloway in Scotland, https://www.ydswg.co.uk/gallery/collections/walls-in-the-landscape

A single-skin wall is built with just one row of stones in width, making it a simpler and less labour-intensive structure compared to double-skin walls. Commonly used for smaller boundary walls and garden features, it provides a functional yet aesthetically pleasing way to define spaces. Although less stable than thicker dry-stone walls, careful stone placement ensures durability, making it a popular choice for decorative and low-structural applications.

2. Double-Skin Wall

A double-skin wall consists of two parallel rows of stones with smaller stones, known as hearting, packed tightly in the centre to enhance strength and durability. This construction method creates a robust and stable structure, making it particularly well-suited for field boundaries and retaining walls. By distributing weight evenly and allowing for natural drainage, double-skin walls have been a longstanding feature of rural landscapes, offering both practicality and longevity.

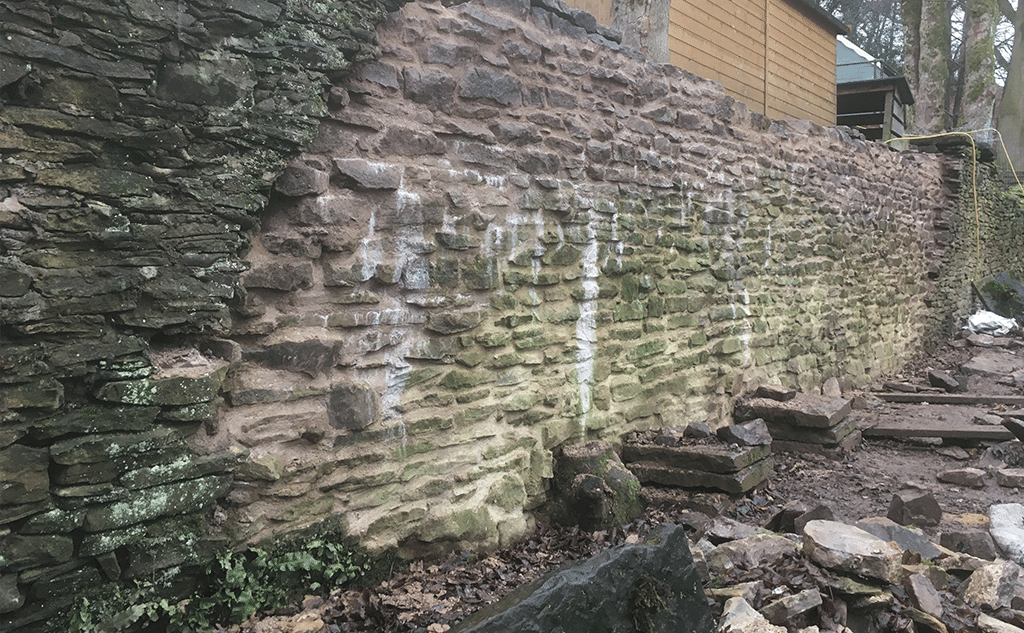

3. Retaining Dry-Stone Walls

Source: https://www.ydswg.co.uk/gallery/collections

Constructed to hold back soil on slopes, preventing erosion and stabilising the landscape. Built using the battered construction technique, where walls lean slightly backward for added strength, they are commonly found in terraces, gardens, and road embankments. Without the use of mortar, these walls rely on the careful placement of interlocking stones to ensure stability, making them a sustainable and long-lasting solution in both rural and engineered settings.

4. Clapper Walls

Source: https://www.ydswg.co.uk/gallery/2021/taster-session/practice-meet-at-high-lodge-farm-scawton-18-july-2021

Clapper walls are constructed using large, flat slabs of stone stacked horizontally without mortar, creating a dry-stone structure that is both durable and weather resistant. This traditional building technique is particularly common in the rugged landscapes of Dartmoor, Devon, and Cornwall, where local stone is readily available. Clapper walls have been used for centuries to enclose fields, define boundaries, and support rural infrastructure, reflecting the region’s long history of stone masonry and vernacular architecture.

5. Hollow Dry-Stone Walls

© Benjamin Andrews via Flickr

Hollow dry-stone walls are designed with internal spaces that allow for natural drainage while also creating habitats for wildlife, supporting biodiversity in rural and garden landscapes. These walls provide shelter for insects, small mammals, and birds, making them an environmentally beneficial alternative to solid masonry. Their porous structure helps regulate moisture levels, reducing the risk of water damage while blending seamlessly into natural surroundings.

Famous Examples of Dry-Stone Walls

-

Yorkshire Dales & Lake District (UK) – Extensive networks of field walls.

-

Hadrian’s Wall – Originally mortared, but now partially dry-stone.

B: Mortared Stone Walls: Strength and Durability in Masonry

Source: https://heritagestonemasonedinburgh.co.uk/the-art-of-stone-walling-exploring-rubble-walling-and-rubble-masonry/

A mortared stone wall is a masonry structure built by binding stones together using mortar (a mixture of cement, lime, sand, and water). This method provides greater stability and longevity compared to dry-stone walls, making it suitable for both structural and decorative purposes. Found in cottages, churches, and historical buildings. Typically seen in traditional construction and restoration projects.

Types of Mortared Stone Walls

1. Rubble Masonry Walls

Source: https://heritagestonemasonedinburgh.co.uk/the-art-of-stone-walling-exploring-rubble-walling-and-rubble-masonry/

Rubble masonry walls are constructed using irregularly shaped stones fitted together with mortar, commonly seen in historic buildings and rural landscapes. There are two main types: coursed rubble, where stones are arranged in horizontal layers for a more structured appearance, and uncoursed rubble, where stones are placed randomly, creating a natural, rustic look.

2. Ashlar Masonry Walls

Source: https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/Ashlar

Constructed using precisely cut and shaped stones, resulting in a uniform, smooth, and polished appearance. This refined masonry technique has been widely used in historic buildings, cathedrals, and classical architecture, where precision and elegance were essential. The tightly fitted stones, often without the need for excessive mortar, create a seamless and durable structure that exemplifies high craftsmanship. Ashlar masonry remains a hallmark of sophisticated stone construction, adding grandeur and permanence to both historical and contemporary architecture.

3. Fieldstone walls

Source: https://www.rootscrafts.com/pendlehill/

Built using naturally occurring stones gathered from the landscape, making them a defining feature of rural areas, farms, and country estates. Their irregular shapes and varied textures give them a distinctive, rustic appearance that blends seamlessly with the natural environment. Traditionally constructed without mortar, some fieldstone walls incorporate mortar to enhance durability while preserving their organic aesthetic. These walls have been used for centuries to define boundaries, enclose fields, and provide structural support, remaining a timeless element of vernacular architecture.

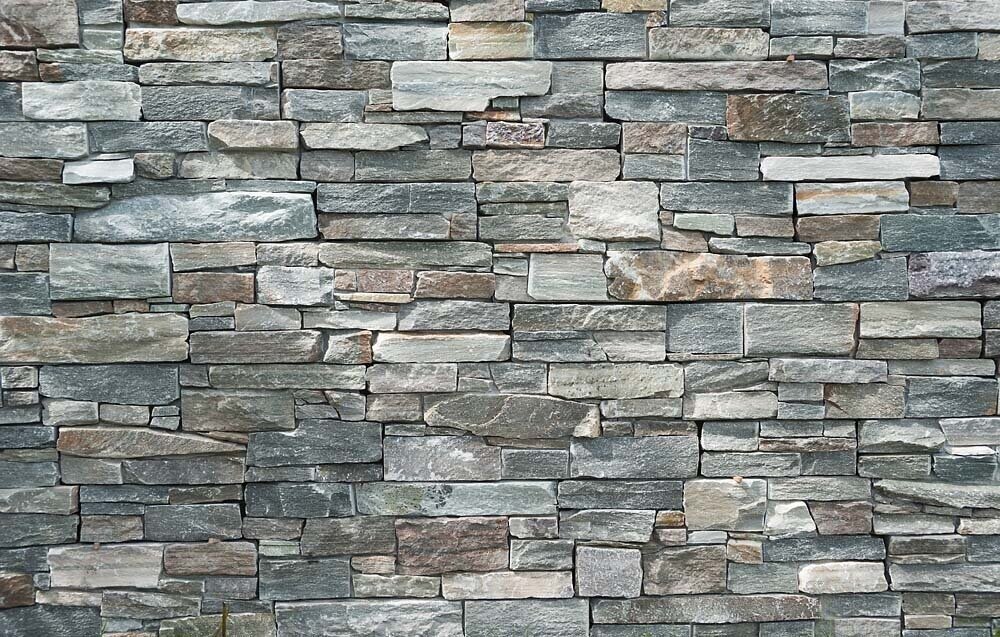

4. Veneer tone walls

Source: https://www.realbrickcladding.co.uk/shop/Stone-Panel-System-Nordic-Real-Stone-Cladding-Quoins-Corners-p590067119

Consisting of a thin layer of stone attached to a structural backing, serving as a decorative façade rather than a load-bearing element. Commonly used in homes and commercial buildings, they enhance architectural aesthetics while providing the appearance of solid stone construction. Veneer can be made from either natural stone or manufactured stone, offering a versatile and cost-effective alternative to traditional masonry. With their ability to replicate the look of full-depth stone walls, veneer stone installations remain a popular choice for both interior and exterior design.

Famous Examples

-

Hadrian’s Wall (UK) – Originally mortared, now partially dry-stone due to erosion.

-

Great Wall of China – Used lime-based mortar to bind stone and brick.

-

Castles & Cathedrals in Europe – Many medieval structures used ashlar masonry with mortar.

C. Field Walls: Traditional Agricultural Boundaries

Field walls are low boundary walls traditionally used to enclose agricultural land, demarcate property, and protect crops or livestock. These walls vary in construction style depending on the region, available materials, and local building traditions. Used in agricultural lands to separate pastures and fields. Often built from local limestone, sandstone, or granite.

Types of Field Walls

1. Limestone or sandstone walls

Limestone or sandstone walls are built using regionally available sedimentary rock, making them a defining feature of many historic and rural landscapes. Commonly found in areas such as the Cotswolds, Ireland, and New England in the USA, these walls are valued for their durability, natural aesthetics, and ability to blend seamlessly with the surrounding environment. Their construction often reflects local building traditions, with carefully fitted stones creating strong, long-lasting structures that require minimal maintenance.

2. Brick or Cob Walls

Brick or cob walls are constructed using either fired bricks or cob, a mixture of clay, sand, and straw, making them particularly common in regions where stone is less abundant. These walls are well-suited to warmer climates, as the materials provide excellent thermal mass, helping to regulate indoor temperatures by keeping buildings cool in summer and warm in winter. Found in traditional architecture across areas such as Tuscany in Italy and Provence in France, brick and cob walls reflect the rich heritage of vernacular construction, blending practicality with regional aesthetics.

3. Hedged Stone Walls

Hedged stone walls combine traditional dry-stone construction with hedgerows or vegetation, creating a reinforced boundary that enhances both stability and biodiversity. Commonly found in Devon, Cornwall, and parts of Wales, these walls serve as natural enclosures for fields and pastures while providing habitats for wildlife. The combination of stone and hedgerows not only strengthens the structure but also integrates seamlessly into the rural landscape, offering an environmentally friendly and long-lasting method of land division.

Famous Examples

-

Dartmoor & Yorkshire Dales (UK) → Extensive networks of dry-stone walls.

-

Burren (Ireland) → Unique limestone walls adapted to rocky terrain.

-

Hadrian’s Wall (UK, Roman-era) → Though not a field wall, it influenced later stone walling techniques.

D. Rubble Walls: Traditional Masonry with Irregular Stones

Rubble walls are masonry structures built using irregularly shaped, rough, or uncut stones, either bound together with mortar or dry-stacked without a binding agent. This construction technique has been used for centuries in various cultures, particularly for rural and vernacular buildings, where locally available materials dictated architectural styles. Their rugged appearance and durability make them a practical choice for agricultural enclosures, field boundaries, and rustic dwellings. Found in regions where quarried or dressed stone was less accessible, rubble walls remain an enduring feature of traditional craftsmanship and landscape architecture.

Types of Rubble Walls

1. Dry rubble walls

Constructed without the use of mortar, relying on the careful selection and precise fitting of irregular stones to create a stable and durable structure. Common in agricultural landscapes, these walls have been a traditional method of enclosure for centuries, particularly in regions such as the UK, Malta, and Ireland. Their interlocking design provides both strength and flexibility, allowing them to withstand environmental pressures while blending harmoniously into the natural surroundings. Often used for field boundaries and rural enclosures, dry rubble walls remain a testament to the enduring skill of traditional masonry.

2. Coursed Rubble Masonry

Coursed rubble masonry is a construction technique in which stones are arranged in roughly horizontal layers, or courses, creating a more structured and uniform appearance than random rubble masonry while still maintaining an irregular shape. This method improves stability and visual consistency while preserving the rustic character of the stone. Commonly used in rural buildings, retaining walls, and traditional masonry structures, coursed rubble masonry strikes a balance between natural aesthetics and structural integrity, making it a durable and time-honoured construction style.

3. Uncoursed (Random) Rubble Masonry

Uncoursed rubble masonry, also known as random rubble masonry, is a traditional construction technique where stones are placed without a strict order or uniform pattern. This method results in a more rustic and natural-looking appearance, often seen in historic rural buildings, boundary walls, and vernacular architecture. While seemingly irregular, the careful selection and skilled placement of stones are essential for ensuring structural integrity. The gaps between larger stones are often filled with smaller stones or mortar to enhance stability, making this technique both practical and visually distinctive.

4. Polygonal Rubble Masonry

Polygonal rubble masonry is a construction technique that utilises multi-sided stones carefully shaped and fitted together in an interlocking pattern. This method enhances structural stability by distributing weight evenly and minimising gaps, reducing the need for mortar in some cases. Often seen in ancient stone construction, particularly in Incan, Roman, and Mediterranean architecture, polygonal masonry showcases the skill of early builders in creating durable and earthquake-resistant structures. Its unique aesthetic, with irregular yet precisely joined stones, continues to be admired for both its engineering ingenuity and timeless craftsmanship.

Traditional Materials Used in English Stone Walls

The type of stone used in English walls varies by region, reflecting the natural geology and local building traditions. Limestone is commonly found in the Cotswolds, Yorkshire Dales, and Peak District, where its warm tones and durability make it a popular choice. Sandstone is prevalent in Northumberland, Cheshire, and Lancashire, known for its strength and weather resistance. Granite, a highly durable and coarse-grained stone, is widely used in Cornwall and Dartmoor, where it withstands harsh coastal and moorland conditions. Slate, valued for its layered structure and natural resilience, is frequently used in the Lake District, Wales, and Cumbria, particularly in roofing and walling. Flint, a distinctive and hard-wearing material, is characteristic of Norfolk, Sussex, and Kent, where it has been traditionally used for both decorative and structural purposes. These regional variations highlight the deep connection between England’s natural resources and its historic masonry techniques.

3. Laws & Regulations for Renovation and New Builds

If you’re planning to renovate or build a stone wall in England, several laws and guidelines apply:

A. Planning Permission

In most cases, you don’t need planning permission for repairing or rebuilding existing stone walls. However, if the wall is in a conservation area or part of a listed building, consent may be required. For new walls over 1 meter (adjacent to a highway) or 2 meters elsewhere, planning permission is necessary.

B. Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas

If your property is Grade I, II, or II listed, any alteration to a stone wall may require Listed Building Consent. Historic England and local councils regulate changes in Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and National Parks.

C. Dry Stone Wall Protection

Many dry stone walls are considered heritage features and protected under local and national policies.

The Countryside Stewardship Scheme provides funding for maintaining traditional walls.

D. Public Rights of Way

If a stone wall borders a public footpath or bridleway, there may be restrictions on changes that impact public access.

4. Restoration & Traditional Building Methods

A. Repairing a Dry Stone Wall

Use original stone as much as possible to maintain authenticity. Rebuild using traditional dry stone techniques without cement or mortar. Ensure proper drainage to prevent erosion and collapse.

B. Mortared Walls and Lime Mortar

Older stone walls often used lime mortar, which is breathable and allows for moisture movement. Using modern cement mortar in a historic wall can cause damage over time.

C. Sourcing Stone

If additional stone is needed, it should be sourced locally to match the existing structure. Many traditional quarries provide reclaimed stone for restoration projects.

Conclusion:

Stone walls are an essential part of England’s rural and historic landscape. Whether you’re restoring a dry stone wall or building a new mortared one, it’s crucial to follow local conservation laws and use traditional materials where possible. Consulting with local experts and authorities will help ensure that your project respects the heritage and remains structurally sound for future generations.

When considering the renovation or construction of such features, it is essential to follow local building regulations, conservation guidelines, and best practices for traditional materials. For listed buildings and properties in conservation areas, obtaining the appropriate permissions from Historic England or the local planning authority ensures that changes respect the integrity of these historic sites. Likewise, using traditional techniques—such as lime mortar for stone cottages and dry stacking for walls—maintains the aesthetic and functional quality of the structures while enhancing their durability.

Beyond legal considerations, there is an increasing emphasis on sustainability and energy efficiency in traditional construction. While historic buildings were not designed with modern insulation or heating methods in mind, sensitive retrofitting—such as sheep’s wool insulation, breathable plasters, and discreet renewable energy solutions—allows these homes to be both comfortable and environmentally friendly.

For those looking to restore a stone wall, preservation over replacement is key. Reusing original stones, rebuilding with traditional stacking methods, and ensuring proper drainage can extend the lifespan of a wall for centuries. Similarly, when designing a new structure in a historic area, matching local stone and architectural styles helps to blend the new with the old seamlessly.

Ultimately, protecting and maintaining England’s traditional stone walls and cottages is a responsibility shared by homeowners, conservationists, and builders alike. By honouring the past through skilled craftsmanship while adapting for the future with sustainable solutions, these structures can continue to be cherished for generations to come. Whether restoring an existing feature or building anew, careful planning and respect for traditional methods will ensure that the beauty and heritage of England’s rural and historic landscapes remain intact.

5. Resources for Stone Wall Restoration

Dry Stone Walling Association (DSWA) – Offers training and guidance on traditional walling techniques. Historic England – Provides legal advice and best practices for conservation. National Trust – Supports the maintenance of traditional stone walls in protected areas. Local Planning Authorities – Check with your council for specific restrictions.