Am crescut deja. Corp și scară - viziune și perspectivă corporală

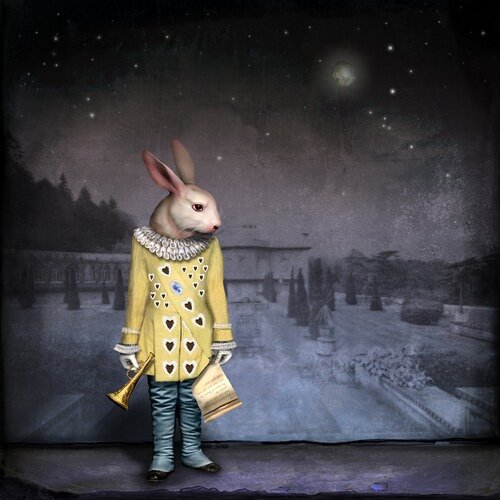

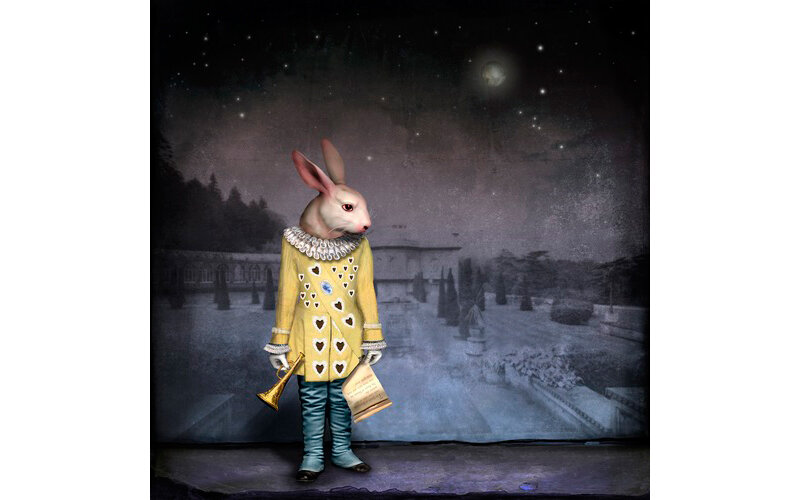

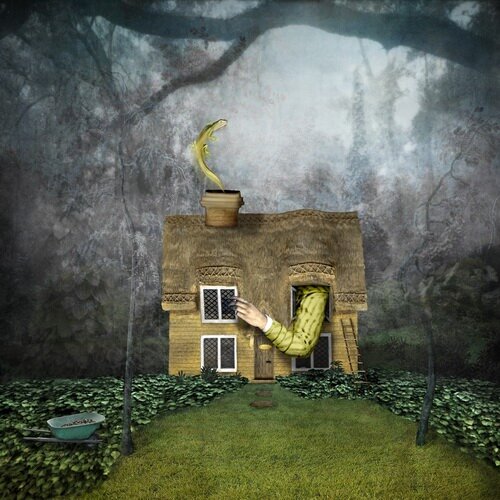

ilustrații: Maggie Taylor

I’M ALL GROWN UP NOW Body and Scale - Vision and Corporal Perspective

| „Primul lucru pe care trebuie să-l fac, își spuse Alice ei înseși - în timp ce hoinărea prin pădure - este să cresc din nou la mărimea mea corectă, al doilea lucru este să-mi găsesc drumul în această grădină minunată. Cred că acesta ar fi cel mai bun plan.”Lewis Carroll, Alice în Țara Minunilor |

|

Ilustrațiile sunt lucrări de artă digitală care fac parte din seria Almost Alice, realizată în anul 2008, incluse în ediția Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll, Modernbook Gallery, Palo Alto, 2008 |

| Ce factori determină dimensiunea uzuală a arhitecturii într-o cultură dominată de imaginile HD?

În fața imaginii Îngerului atașat, de Jean Nouvel, pe întreaga înălțime a Turnului situat în intersecția Smichov1, din Praga, suntem pierduți între scara micșorată a propriului corp și supradimensionarea orașului. Asistăm la o detașare a scării arhitecturale de la conceptele de MACRO și MICRO, influențată simultan atât de determinarea vizuală, cât și de percepția senzorial corporală. Ce semnificații mai au gradațiile mic sau mare, când singura entitate stabilă rămane corpul și unica variabilă este arhitectura? În confruntarea cu ordinul colosal retrăim senzațiile primilor ani ai vieții, când nu puteam escalada o bancă și trăiam într-o lume prea mare. Dincolo de funcțiunea de reprezentare a monumentalului, regăsim o percepție primară a dimensiunilor și materialelor incerte. Afluența vizuală a fantasticului ultimelor decenii contribuie la această stare în care corpul poate fi la fel de mic/mare cât un iepure sau o cană. Juhani Pallasmaa observa că arhitectura ar trebui să „domesticească spațiul nelimitat și să ne faciliteze ocuparea sa”, concomitent să ne ajute „să domesticim timpul și să locuim continuumul temporal”2. Timpul și spațiul redevin cuplul determinant al arhitecturii, în defavoarea imaginii, construitul fiind o traducere subiectivă a propriilor rapoarte cu mediul, arhitectura redeterminându-se în baza percepțiilor experiențiale. Repoziționarea omului modern și contemporan în spațiu reia vechile întrebări filosofice legate de casă și corp: casa ca dimensiune interioară, casa - proiecție a experiențelor spațiale, casa - alegoric in corpore, casa - cadru în percepția scenografică, spațialitatea determinată/asimilată corporal. De-a lungul istoriei, teoriile au pus frecvent în relație corpul și spațiul într-o determi-nare matematică a părților, cu o reprezentare specifică a proporțiilor dintre om și construit. Omul apare în reprezentările religioase ale Evului Mediu ca entitate dominantă a spațiului/cadrului printr-un artificiu de manipulare psihologică, personajele din prim-plan având scara amplificată pe măsura importanței. Imaginile picturale redau aparent în „secțiune” obiectul arhitectural și personajele la o scară mult mai mare decât cea reală. Giotto di Bondone reintroduce spațialitatea-cadru în care sunt inserate perso-najele în defavoarea arhitecturii pasive tip fundal în lucrările de referință în Bazilica de Sus din Assisi și în Santa Croce, din Florența. În Legenda Sfântului Francis - Miracolul crucifixului, Giotto amplifică proporția omului în casă, minimalizând importanța cadrului arhitectural. O relație directă de subordonare o constatăm în lucrarea Ognissanti Madonna, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (cca. 1310). Regăsim o expresie similară din punct de vedere al raportului corp-casă și în lucrările lui Ambrogio Lorenzetti, printre care Alegoria bunei și relei guvernări și efectele lor asupra orașului și zonelor câmpenești3 (1337-’39). Rudolf Arnheim remarca, în Arta și perceția vizuală4, tipologia particulară a reprezentării: construcțiile reprezentate fiind tăiate (secționate), arhitectura rămâne un înveliș al corpului, cu unic rol de contextualizare - „Invenția copilului dăinuie de-a lungul veacurilor, astfel că, până și în arta foarte realistă a unui Dürer sau Altdorfer, Sfânta Familie se adăpostește într-o clădire fără peretele din față, care este camuflat neconvingător ca o ruină prăbușită”. Reprezentările arhitecturale evoluează către Renaștere și Baroc, aducând la scară omul și integrându-l în spațiu ca parte constitutivă. Casa în sensul spațial tridimensional începe să se dezvolte în reprezentare ca proiecție corporală în termenii antropometriei. Mergând pe tradiția inițiată de Vitruvius în secolul 1 î.H., omul a redevenit pe deplin măsura universului în secolul al XV-lea, prin lucrările lui Leone Battista Alberti5. Pe de-o parte, el este omul universal (vitruvian) din 1490 al lui Leonardo da Vinci, omul perfect, pe de altă parte - model al simetriei și proporțiilor în ecranizarea Frankenstein, a lui Mary Shelley. Omul stă la baza geometriei planimetrice în Renaștere și devine, în 1948 și în 1955, modulorul lui Corbusier, unitate antropometrică a lucrurilor. În particular, remarcăm accentul lui Leo-nardo da Vinci, dincolo de ajustarea formulelor lui Vitruvius și Alberti, dubla îns-criere a omului în cerc și pătrat - două centre diferite ale corpului, de „mărime/magnitudine” și „gravitație”… respectiv două relaționări arhitectural distincte6. Magnitudinea ține de ocuparea spațială, contrar gravitației care așază corpul într-o rela-ție indestructibilă cu planul orizontal. Nu întâmplător, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, în Micul Prinț7, descria poziționarea vizavi de acasă prin primul atribut spațial al mărimii - „la mine acasă e atât de strâmt” - deși se găsea pe suprafața infinită, orizontală, a asteroidului B621. Aceeași spațialitate redusă era metaforic ilustrată de Omul Copac, în tripticul pictural Grădina Edenului8. Hieronymus Bosch interpreta pântecul atât prin relația de includere, cât și prin cea de agresivitate torționară, amintind de mecanismele de tortură folosite în Evul Mediu - taurul de bronz -, respectiv, de colivia supradimensionată. Cam- pania publicitară pentru Lavazza în 2011, într-un joc al imaginii comerciale care speculează mărimea coordonând-o impor-tanței, reabordează personajul scalat al lui Lewis Carroll (Alice) ca om vitruvian, înscris într-o cană. Subordonarea spațială este, în interpretare iconică, măsură a tuturor lucrurilor. Omul vitruvian este reinterpretat în sensul originar al geometriei, măsura lucrurilor care-și modifică substanța în funcție de el. Întreaga campanie mizează pe acest joc al scării umane, după moda altor versiuni publicitare care, în ultimul deceniu, reactualizează lumea fantastică din „Alice în Țara Minunilor”, exemplu: editorialul semnat de Annie Leibovitz pentru Vogue US, din decembrie 2003. În 1865, în nuvelele Alice în Țara Minunilor9, Ce a găsit Alice10 și Alice în Țara Oglinzilor11, Lewis Carroll își vedea personajul principal crescând și descrescând, având o dimensiune fantastică raportată la spațialitatea arhitecturală (planul real). Raportul corp-scară apare într-o ipostază tipică în imaginar, unde - în contextul creșterii - corpul real se raportează la o machetă a casei. Schimbarea de optică produsă la sfârșitul secolului al XIX-lea era determinată de fascinația pentru curiozități, așa cum remarcăm în seria de lucrări a lui Joseph Cornell, lucrări care reiau arhitectura în sensul lumilor miniaturale: Palatul Roz (Pink Palace, 1946-'48), Scenografie pentru o lume de poveste (Setting for a Fairy Tale, 1942). Ilustrațiile semnate de Maggie Taylor pentru ediția Modernbook Gallery a Alice în Țara Minunilor12 reiau în fundal o tipologie a casei victoriene pe care aproape toate ecranizările după Lewis Carroll le-au utilizat. Atmosfera obscură a casei rigide se pliază pe starea interioarelor întunecate în casa Antony13, construită la începutul secolului al XVIII-lea, locație a filmărilor din Alice în Țara Minunilor, în regia lui Tim Burton14. Cu puternice surse în viziunea secolului al XIX-lea (Lewis Carroll), cinematografia (frecvent în filmele horror) vede casele de păpuși cel mai adesea în forma lor originară, a machetelor caselor victoriene. Aluzia vizuală încorporează frica inconștientă a omului care nu își mai găsește locul în lume, pentru care scara lucrurilor se schimbă odată cu maturizarea. Spațiul arhitectural autentic, în contextul deformărilor corpului, adesea în urma creșterii, devine neîncăpător, strâmt. În 1920, Le Corbusier aducea în arhitectură scara vagonului de dormit ca scară necesară, suficientă, igienică a locuinței, un manifest al modernismului, al interiorului minimal. În desenele sale se constată o fragmentare, o îngrămădire repetitivă a elementelor care trebuie să încapă într-un spațiu, într-o ramă (Căderea Barcelonei - Chute de Barcelone I, 1939/1960). Modulorul, ca scară interioară a lucrurilor, determină unul din conflictele reale ale arhitecturii, care nu face diferența între scara minimală și cea confortabilă în Unitatea de locuit de la Marsilia15 din 1952. Într-o varinantă timpurie, în complexul de la Weissenhof16 din 1927, Le Corbusier aborda funcțiunea compresată ca artificiu vizual de dilatare spațială. Într-o minimalizare a spațiului „inutil”, dormitorul era redus la o unitate mobilă, pliabilă și spațiul de zi amplificat. O serie de exemple ale arhitecturii contemporane speculează spațiul strâmt ca fiind esențial, necesar. MVRDV, în viziunea casei arhetipale, proiectează interioarele locuințelor sociale ca având o spațialitate minimă. Întreaga locuință Didden Village17 din Rotterdam, Olanda (2002-2006), funcționea-ză pe principiul spațiului comprimat, ideea fiind reprezentativ ilustrată în dormitoarele copiilor. Camera copiilor materializează spațiul „strâmt” ca unul de extensie a locului de dormit. Dormitorul devine în utilizarea celor mici o cutie, geamul supradimensionat acționează ca o trapă care dă pe acoperiș. În contextul imaginar spațial al cuplului corp-casă, Alice în Țara Minunilor constituie referința care descrie maturizarea ca o creștere agresivă spațial, în care construcția devine neîncăpătoare. Nuvela, ulterior versiunea cinematografică regizată de Tim Burton, dezvoltă imagini arhitecturale arhetipice, reluate și de Guillermo del Toro în Labirintul Faunului18. Așa cum am amintit anterior, proiecția imaginară arhitecturală cuprinde, de cele mai multe ori, propria percepție corporală, ca o reflexie spațial subiectivă a poziției în lumea construită. Casa nu apare în Alice în Țara Minunilor în sensul de personaj principal, dar este mediul în care fantasticul este introdus de cuplul casă-corp. Dimensiunea poveștii debutează odată cu creșterea și descreșterea fetiței în spațiul interior - într-o cameră - respectiv odată cu distorsionarea percepției comune despre scara umană. Psihiatrul John Todd remarca, în 1955, modificările „imaginare” ale percepției - vizuale, auditive, tactile - descrise de Lewis Carroll ca fiind mai mult decât o iluzie spațială. De amintit este și că scriitorul suferea de migrene și era familiarizat cu interpretarea psihiatrică a tulburărilor de percepție. Sindromul AIWS (Alice in Wonder Land) descrie tulburarea psihiatrică prin dubla alterare a percepției, corporale și vizuale, în sensul modificării scării obiectelor/membrelor. Imaginea corporală distorsionată, percepția eronată a diverselor părți ale corpului, supradimensionarea mâinilor și a capului, frecvent însoțită de pierderea simțului timpului, amintite de John Todd și de Lewis Carroll, sunt asociate stării de disconfort spațial și psihologic. Mijlocul secolului al XX-lea proiectează intenționat mitul Alice în Țara Minunilor în sensul perspectivelor psihedelice, în cinematografia alb-negru și în fotografie; ne referim, în particular, la ecranizarea din 1966 în versiunea regizorului Jonathan Miller. Influența se manifestă ca o preferință vizuală certă, pe fondul experimentărilor în fotografie și a textelor vremii: Uși ale percepției (Doors of Perception) -- de Aldous Huxley, Experiențe psihedelice (Psychedelic Experience) - de Timothy Francis Leary, Cartea Tibetană a Morților (The Tibetan Book of the Dead). Viziunea arhitecturală, după cum o va reproiecta și regizorul Tim Burton în 2010, este aceea a casei victoriene văzută în sensul spațiilor dominate de clarobscur, a experimentelor fotografice, a spectacolului curiozităților. Spațiul interior, în termenii casei, este văzut de Miller în ecranizarea sa ca o închisoare20, o cutie care se strânge imperceptibil în jurul copilului care crește și nu mai vede lumea înconjurătoare cu ochii inocenței. „Pe mâini sigure (ale lui Miller) Alice în Țara Minunilor nu este o simplă poveste fantastică despre omizi, șoareci și regine sângeroase ce caută să-și decapiteze supușii, ci este mai degrabă călătoria unei tinere fete britanice prin care aceasta devine conștientă de sine și se maturizează, în condițiile în care este prizonieră în cadrul unui coșmar victorian…”21, remarca Scott Thill în Bright Lights Film Journal. Interpretarea regizorului trimite către schimbarea de scară, care se declanșează odată cu creșterea - „umbrele casei-închisoare încep să se închidă în jurul copilei în creștere, și asta mi se pare că a fost exact la ceea ce se gândea Dogdson atunci când descria cele două aventuri ale lui Alice, una în Țara Oglinzilor, cealaltă în Țara Minunilor”22. În contextul modificărilor percepției, asistăm la o dinamică atipică: parcugerile imposibil temporale ale spațiului sunt depășite de noile căi de acces - trecerile prin oglindă -, de permeabilitatea materialelor, de modificarea spațială a arhitecturii construite în funcție de artificiile perspective (vizibilă în cinematografie). Una din succesiunile tipice ale intrigii din Alice în Țara Minunilor este abandonarea spațiului. Cel interior nu crește simultan și nu își modifică rapoartele determinate, păstrându-și aparența reală și scara obiectelor de mobilier. Casa devine o cutie inutilă și, ca urmare, arhitectura încetează să mai conțină corpul care nu o mai poate ocupa, orientându-se spre noi repere ale realității. Aparent antitetic lumii lui Alice, universul asteroidului B621 pe care trăiește Micul Prinț este prea strâmt, descris prin atributele spațiale ale cadrului contruit, deși, paradoxal, pe noua planetă nu există nicio casă, doar „acasă”. „Unde e «acasă la tine»? [...] Micul Prinț rosti atunci cu multă seriozitate: - Nu-i nimic. La mine-acasă e atât de strâmt. Și, cuprins de-o ușoară me-lancolie, adăugă: - Unde-oi vedea cu ochii nu poți ajunge prea departe... ”23 Povestea Micului Prinț despre copilărie, inocență și singurătate pleacă de la aparențele vizibile ale reprezentării24 și vorbește despre o claritate specifică copilăriei de a percepe lumea și rapoartele cu ceilalți, de a-și apropia spațiul, de a se identifica cu obiectele. Diferența dintre casă și acasă, așa cum o proiectează Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, se traduce în excluderea cojii construite - acasă devine spațiul deținut, marcat într-un sens aproape originar de activitățile zilnice. Universul asteroidului B62125 este concentrat, „strâmt”, descris paradoxal prin atri-bute spațial senzoriale. Micul Prinț aduce spațiul arhitectural existențial la un minim abstract, simbolic. Spațiul, deși deschis, are o „intimitate” proprie singularului, a spațiului neîmpărtășit care aparține unei singure persoane. Spațialitatea condiționată de măsura corpului în sensul constrângerii este o categorie aparte, formală, definită prin cuplul conținut-conținător. Spațiul suficient nelimitat din Micul Prinț și cel insuficient din Alice în Țara Minunilor, ambele croite pe măsura omului, sunt ipostaze radicale ale imaginarului corporal-spațial care reflectă proiecția arhitecturală prin prisma stărilor interioare. Casa se traduce ca o materializare a limitărilor personale, o reinterpretare a dasein-ului heideggerian. Ea este cadrul originar cu care corpul intră în contact într-o percepție senzorială privilegiată, casa strâmtă a cărei conștientizare este amplificată de constrângerea spațială. Omul ca scară a lucrurilor își modifică dimensiunile raportat la cadrul arhitectural în Alice în Țara minunilor, devenind intrigă a dimensiunii fantastice. Simbolic, el depășește măsura lucrurilor care nu i se mai potrivesc, lumea devine prea mică - problema percepției contemporane în progresie. Camera fizică, ce este depășită, nu mai este condiționată matematic de scara omului, nu crește în sensul modulorului, nu explodează, nu se descompune; devine doar insuficientă, limitată în sensul constrângerii. Dimensiunea fantastică este dată de diferența vizuală dintre cadru si conținut - Alice crește dilatându-se într-o cameră, ajungând să nege determinarea construcției. Casa devine prea mică pentru a mai cuprinde corpul și aspirațiile sale. Complementar, spațiul arhitectural devine un cadru tactil, haptic, într-o suprasensibilizare a corpului vizavi de limite. „Curând ochii (fetiței) se opriră asupra unei cutii mici de sticlă, care stătea sub masă: ea o deschise și descoperi înăuntru o prăjitură foarte mică, pe care scria cu afine MANÂNCĂ-MĂ. «Ei, o să o mănânc», spuse Alice, «și dacă mă va face să cresc mare, voi putea să ajung la cheie, dacă mă va micșora, voi putea să mă strecor pe sub ușă: în ambele cazuri voi reuși să intru în grădină și nu-mi pasă în ce fel.»”(Lewis Carroll, Alice în Țara Minunilor) |

| * Ana Maria Crișan

este doctor arhitect, asistent în cadrul Departamentului Sinteză de Proiectare, la Universitatea de Arhitectură și Urbanism „Ion Mincu”, București.

** Maggie Taylor (născută în 1961) este fotograf și artist digital, cunoscută pentru viziunea particulară exprimată în fotomontaje, din Gainesville, Florida, Statele Unite. Pe fondul dublei specializări în filosofie (Yale, 1983) și fotografie (Universitatea din Florida,1987), lucrările sale prezintă influențe suprarealiste. Acestea se găsesc în diverse colecții printre care: The Art Museum, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ; The Center for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ; The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA; The Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, AL; Musee de la Photographie, Charleroi, Belgium; Museet For Fotokunst, Odense, Denmark; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX; NationsBank, Charlotte, NC; and the Prudential Insurance Company, Newark, NJ e.t.c. www.maggietaylor.com |

| NOTE:

1. Jean Nouvel, Turnul Îngerului de Aur, Praga, 2000. Jean Nouvel, speculând folclorul local al îngerului păzitor, a încorporat imaginea pe fațada de colț a clădirii, străjuind râul Vltava și ruinele Vysehrad,. Reproducerea îl înfățișează pe actorul Bruno Ganz, „îngerul” din filmul Wings of Desire, de Wim Wenders, 1987. Clădirea a propus unificarea a patru construcții existente sub o fațadă cortină, înaltă de 32,5 m, fiind receptată critic sub aspectul scării, materialelor și iconografiei. 2. Juhani Pallasmaa - The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. West Sussex: Academy Press; 2nd edition, U.K., 2005. 3. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Effetti del Buon Governo in città, 1338-1339, Sala della Pace, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. 4. Rudolf Arnheim - Arta și percepția vizuală. O psihologie a văzului creator, ediția a II-a, traducere de Florin Ionescu, Polirom, București, 2011, p. 198. 5. Alberti, Leon Battista - On the Art of Building. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1991. 6. cf. Keele apud Michael John Gorman - STS 102: „Leonardo: Science, Technology, and Art” , Stanford University, accesat 05.12.2011 - http://leonardodavinci.stanford.edu /submissions/clabaugh/history/leonardo.html 7. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au ebooks03/0300771h.html, accesat 02.03.2012. 8. Hieronymus Bosch, The garden of Earthly delights (Grădina Edenului), sau The Millennium, ulei pe lemn, triptic, 220×389cm, 1503-1504, Muzeul Prado, Madrid. 9. Lewis Carroll - Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, ilustrații: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1865, PDFreeBooks.org; Carroll, Lewis - Alice în Țara Minunilor. Traducere: Elisabeta Gălățeanu, ilustrații: Mabel Lucie Attwell. București: Editura Tineretului, 1958. 10. Lewis Carroll - What Alice Found There, ilustrații: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1871, PDFreeBooks.org. 11. Lewis Carroll - Through the Looking-Glass, ilustrații: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1871, PDFreeBooks.org. 12. Ilustrații: Maggie Taylor pentru Lewis Carroll‘s Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, autor: Lewis Carroll, Modernbook Gallery, Palo Alto, 2008. 13. Antony Estate, Torpoint, Cornwall, PL11 2QA; datat la începutul sec. al XVIII-lea. Amenajare peisagistică semnată de Reginald Pole Carew, Humphry Repton (c. 1790), accesat 03.02.2012 - http://www.gardensofcornwall.com/outdoor-kids/antony-house-and-garden-p133063 14. Alice in Wonderland, regie: Tim Burton, scenariu: Linda Woolverton, după nuvelele lui Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865, și Through the Looking-Glass, 1871, producție: Walt Disney Pictures, Roth Films, Team Todd, Zanuck Company, 2010. 15. Le Corbusier, Unitatea de locuire (Unité d‘habitation, Cité Radieuse), Marsilia, Franța, 1952. 16. Le Corbusier, Complex Weissenhof, Stuttgart, 1927. 17. MVRDV, Didden Village, Rotterdam, Olanda, 2002-2006. 18. El Laberinto del Fauno, regie, scenariu: Guillermo del Toro, coproducție: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, în asociere cu: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM; 2006; 19. Alice in Wonderland, regie: Jonathan Miller, productie: BBC, Jonathan Miller Adaptation, scenariu Jonathan Miller, după o nuvelă de Lewis Carroll, 1966. 20. „Umbrele casei-închisoare încep să se închidă în jurul copilei în creștere, și asta mi se pare că a fost exact la ceea ce se gândea Dogdson atunci când descria cele două aventuri ale lui Alice, una în Țara Oglinzilor, cealaltă în Țara Minunilor” - Jonathan Miller, apud Scott Thill, Bright Lights Film Journal, noiembrie 2003 | Issue 42, http://brightlightsfilm.com/42/alice.php, accesat 02.03.2012. 21. Scott Thill - Bright Lights Film Journal, noiembrie 2003 | Issue 42, http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/42/alice.php, accesat 01.02.2011; 22. Jonathan Miller, apud Scott Thill, ibidem. 23. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, accesat 02.03.2012, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html. 24. Ironia din introducerea cărții, parabola reprezentării unui șarpe Boa, face trimitere la propria experiență a autorului și, respectiv, la studiile eșuate în arhitectură din tinerețe. 25. „Planeta de pe care venea Micul Prinț e asteroidul B612”- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry - Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accesat 02.03.2012. Alberti, Leon Battista - On the Art of Building. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1991. Arnheim, Rudolf - Arta și percepția vizuală. O psihologie a văzului creator. Traducere: Ionescu, Florin. București: Editura Meridiane, 1979. Carroll, Lewis - Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, ilustrații: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1865, PDFreeBooks.org. Carroll, Lewis - Alice în Țara Minunilor. Traducere: Elisabeta Gălățeanu, ilustrații: Mabel Lucie Attwell. București: Editura Tineretului, 1958. Carroll, Lewis - What Alice Found There, ilustrații: John Tenn, Macmillan, PDFreeBooks.org, 1871. Carroll, Lewis - Through the Looking-Glass, ilustrații: John Tenn, Macmillan, PDFreeBooks.org, 1871. Crișan, Ana Maria - Anagrama arhitecturii imaginare. Metamorphosis - reevaluarea paradigmei temporale în arhitectură, teză de doctorat, 2012 Pallasmaa, Juhani - The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. West Sussex: Academy Press; 2nd edition, U.K., 2005. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accesat: 02.03.2012. Thill, Scott - Bright Lights Film Journal, noiembire 2003 | Issue 42, http://brightlightsfilm.com/42/alice.php, accesat: 02.03.2012. |

| “«The first thing I’ve got to do», said Alice to herself, as she wandered about in the wood, «is to grow my right size again; and the second thing is to find my way into that lovely garden. I think that will be the best plan.”1 |

|

Illustrations: Digital artwork, Copyright Maggie Taylor, Almost Alice Series, 2008; illustrations included in the Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland edition, Lewis Carroll, Modernbook Gallery, Palo Alto, 2008. |

| What are the factors that determine the usual size of the architecture in a culture dominated by HD images?

In front of the Jean Nouvel’s The Golden Angel image, stretched over the entire height of the Tower located in Smichov2, Prague, we are suspended between the reduced scale of the body and the over-dimensioning of the city. We are witnessing a detachment of the architectural scale from the MACRO and MICRO concepts, simultaneously influenced by the visual determination as well as by the sensory perception. What meanings may hold the small or large graduations, when the only constant entity refers to the body and the only variable is the architecture? In dealing with the order of colossal, we relive the early years of our life, when we could not escalate a bench and we were living in a world too big for us. Beyond the function of the representation of the monumental, we find a primary perception of the dimensions and of the uncertain materials. The visual influx of the fantastic from the last decades contributes to this condition where the body may be as large/small as a rabbit or a cup. Juhani Pallasmaa notices that architecture should “tame the unlimited space and facilitate its occupation”, while helping us “to tame the time and dwell in a temporal continuum”3. Time and space becomes the determining couple in architecture, being preferred to the image; the built environment is a subjective translation of the personal connections with the environment as architecture re-determines itself according to the experienced perceptions. The reposition of the modern and contemporary human in space resumes the old philosophical questions related to house and body: the House as an inner dimension; the House as a projection of spatial experiences; the House - allegorically in corpore; the House - a frame in the scenery design perception, where the spaciousness is corporeally determined/assimilated. Throughout history, the theories put frequently in relationship the body and the space in a mathematical determination to the parts, with a specific representation of the proportions between the man and the built environment. In the religious representations of the Middle Age, man appears as the dominant entity of the space/framework through an artifice of psychological manipulation, where the characters in the foreground are magnified according to their importance. The pictorial images apparently illustrate in “transaction” the architectural object and the characters at a much larger scale than they are in reality. Giotto di Bondo-ne reintroduces the spaciousness-setting, where the characters are inserted over the background-type passive architecture, as in his reference works in the upper Basilica of Assisi and Santa Croce, in Florence. In the Legend of St. Francis - the Miracle of Crucifixes, Giotto amplifies the human proportion in the house, minimizing the importance of the architectural fra-mework. We find a direct relationship of subordination in Ognissanti Madonna, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena (c. 1310). We find a similar phrase in terms of the body-house in the works of Ambrogio Lorenzetti, for instance, in Effects of Bad Government in the City4, (1337-' 39). In Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye5, Rudolf Arnheim remarks the particular typology of representation: the represented constructions are being clipped (cut off) while architecture remains a body layer with an unique contextual role - "The Invention of the child endures throughout the ages, so that even in the very realistic art of Dürer or Altdorfer, the Holy Family houses in a building without the front wall, which is camouflaged in a non-persuasive way as a collapsed wreck". Architectural representations evolve to-wards Renaissance and Baroque, bringing man to his proper scale and integrating him into space as a constituent part. The House, as a three-dimensional space, begins to develop in the representation as a corporeal projection in terms of anthropometry. Following the tradition initiated by Vitruvius in the 1st century B.C., in the 15th century, man has become the complete measure of the universe, through the work of Leone Battista Alberti6. On the one hand, he is Leonardo da Vinci’s universal man - the Vitruvian Man - in 1490, the perfect man; on the other hand, he is the model of symmetry and proportions in Mary Shelley’s film Frankenstein. The man is behind the plan type geometry in Renaissance and becomes once again, in 1948 and 1955, Le Corbusier’s Modulor, the anthropometric unit of things. In particular, we note the focus of Leonardo da Vinci beyond adjusting the formulae of Vitruvius and Alberti, the double framing of man in a circle and a square - two different centers of the body “size/magnitude” and “gravity”, two distinct architectural relationships7. The magnitude depends upon space occupation, contrary to the gravity that places the body in an indestructible relationship with the horizontal plane. Not incidentally, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in The Little Prince8 described the position opposite to home through the first attribute of space-size "at home is so tight" - although it was on the infinite, horizontal surface of the B621 asteroid. The same reduced tridimensionality was metaforicaly illustated by the Tree Man in the three painting set The Garden Of Eden9. Hieronymus Bosch was interpreting the belly both as inclusion relation and as tortionary aaggression, reminding such the torture mecanisms used in Middle - Ages the bronze taurus -, respectively, the oversized birdcage. The advertising campaign for Lavazza in 2011, in a game of the commercial image that speculates the size according to its importance, approaches the scaled character of Lewis Carroll (Alice) as a Vitruvian Man, inscribed in a cup. In an iconic interpretation, the spatial subordination is the measure of all things. The Vitruvian Man is reinterpreted in the originar sense of geometry; it is the measure of things that change their substance according to him. The whole campaign rests on this game of human scale, following the trend set by other advertising versions that update the fantastic world of „Alice in Wonderland”, for instance: the column signed by Annie Leibovitz for Vogue US, in December 2003. In 1865, in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland10, What Alice Found There11 and Through the Looking-Glass12, Lewis Carroll sees the main character growing and shrinking, having a fantastic dimension, related to the architectural spaciousness (real plan). The ratio body-scale appears in a typical stance in the imaginary, where - in the context of growth - the real body relates to a form of the House. The optical shift produced at the end of the 19th century is determined by his fascination for curiosities, as we note in the works of Joseph Cornell, that include architecture in miniature worlds: Pink Palace (1946-’48), Setting for a Fairy Tale, (1942). The illustrations, signed Maggie Taylor for the Modern book Gallery edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland13, retrace as a background the typology of the Victorian house that is to be found in almost all film adaptations after Lewis Carroll. The dark atmosphere of the rigid house folds on the dark interiors in Antony House14, built at the beginning of the 18th century, the location of the filming of Alice in Wonderland, directed by Tim Burton15. With deep roots in the 19th century (Lewis Carroll), the cinematography, in its horror productions, usually sees dollhouses most frequently in their originate form, as Victorian house forms. The visual hint incorporates the unconscious fear of man that cannot find his place in the world, for whom the scale of things changes alongside with his growing up process. In the context of distortions of the body, often as a result of growth, the authentic architectural space becomes tight, lacking spaciousness. In 1920, Le Corbusier brought in architecture the scale of the sleeping wagon as the proper scale for the necessary, sufficient, hygienic housing, a manifesto of modernism, of the minimal Interior. In his designs we can perceive a fragmentation, a scrimmage of the repetitive elements that must fit into a space, in a frame (The Fall of Barcelona-Chute de Barcelone, 1939/1960). The Modulor, as the inner scale of things, determines one of the real conflicts of architecture that does not make the difference between the minimal scale and the comfortable scale in the Living Unit at Marseilles16 in 1952. In an earlier vision, in the Weissenhof Complex17 from Stuttgart, in 1927, Le Corbusier interpreted the compressed function as a visual artifice of spatial expansion. By minimizing the „useless” space, the bedroom was reduced to a mobile unit that could be folded, while the living space was amplified. A number of examples from the contemporary architecture speculate the tight space as being essential, necessary. In the archetypal House vision, MVRDV designs the interiors of social housing as having a minimum widening. The entire Didden Village18 dwelling in Rotterdam, Netherland (2002-2006), works on the principle of the compressed space, the idea being representatively illustrated in children's bedrooms. The children's room materializes the "tight" space as an extension to the sleeping place. The bedroom used by the little ones becomes a small box, the oversized window acts as a trap door that gives onto the roof. In the context of the spatial imaginary of the body-house couple, Alice in Wonderland is the reference that describes the growing up as an aggressive process in space, where the built environment becomes small. The novel, and subsequently the film version directed by Tim Burton, develops archetypal architectural images, later replayed by Guillermo del Toro in El Laberinto del Fauno19. As I have previously mentioned, the architectural imaginary projection comprises, most of the times, its own corporeal perception as a spatially subjective reflection of one’s position in the built world. The House does not appear in the Alice in Wonderland as the main character, but it is the environment where the fantastic is introduced by the couple body-house. The story starts with the growing and shrinking of the little girl in the inner space, a room that is the distortion of the common perception about the human scale. In 1955, the psychiatrist John Todd remarks the “imaginary” changes of the perception - visual, auditory, tactile - described by Lewis Carroll as being more than a spatial illusion. Remember that the writer was suffering from migraines and he was familiar with the psychiatric interpretation of perception disorders. AIWS syndrome (Alice in Wonder Land) describes the psychiatric disorder by the double alteration of perception, both corporeal and visual, as the scale of objects/limbs modifies. The distorted corporeal image, the erroneous perception of the various parts of the body, the oversized hands and head frequently accompanied by the loss of sense of time mentioned by John Todd and Lewis Carroll, are associated with the state of spatial and psychological discomfort. In the mid-20th century, the Alice in Wonderland myth is designed on purpose from psychedelic perspectives in black and white cinematography and photography; we refer, in particular, to the 1966 film version of director Jonathan Miller20. The influence is manifested as a definite visual preference, amid the experiments in photography and literature of the time: Doors of Perception by Aldous Huxley, Psychedelic Experience by Timothy Francis Leary, The Tibetan Book of the Dead. The architectural vision, as it will be redesigned by director Tim Burton in 2010, is that of the Victorian house seen as a space dominated by chiaroscuro, it is a world of photographic experiments, a display of curiosities. In terms of the House, the inner space is seen in Miller’s film as a prison, a box that cuddles imperceptibly around the child that grows and no longer sees the surrounding world with the eyes of innocence. Scott Thill, in Bright Lights Film Journal, wrote: “In his assured hands, Alice in Wonderland is not merely a fantastical tale of caterpillars, mice, and bloodthirsty queens looking to off some heads, but rather a journey of self-realization and maturation for a young British girl locked in a Victorian nightmare filled with, […]adults executing matters of consequence....”21. The director›s interpretation sends to the change of scale, which operates alongside with Alice’s growth: «The house-prison shadows begin to close around the growing child, and it seems to me that was exactly what Dodgson was thinking when he described the two adventures of Alice, one in the Mirror Land, the other in Wonderland”22. In the context of changes in perception, we are witnessing an atypical dynamics: the time-impossible space crossings are outdated by new roadways-crossings through the looking glass, by the permeability of the materials, by the spatial changing of the built architecture according to the artifices of the perspective (visible in the film industry). One of the typical successions in the Alice in Wonderland plot is abandonment of the space. The interior does not increase simultaneously and does not change their determined reports, while retaining the real appearance and the scale of the objects and the furniture. The House becomes a pointless box and, as a result, the architecture ceases to bear the body that no longer can dwell in it, directing it towards new milestones of reality. Apparently antithetical to the world of Alice, the universe asteroid B621 where the Little Prince lives is too tight, is described by the spatial attributes of the built frame, although, paradoxically, there is no house on the new planet, it is just “home”. “Where’s «home to you»? [...] The little Prince utter then with much seriousness: - It’s nothing. In my home it’s so tight. And, a slight melancholy, he added: -Where the sheep see with your eyes can’t get too far...”23 The story of the Little Prince about his childhood, innocence and solitude starts from the visible appearances of representation24 and speaks about a type of clarity typical for the childhood to perceive the world and relate to others, to approach the space, to identify with the objects. The difference between House and Home, as described by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, is interpreted as the exclusion of the built shell; the home becomes the owned space, marked, in an almost originate sense by the daily activities. The universe of B62125 asteroid is focused, "tight", described paradoxically through spatial attributes. Little Prince brings the existential architectural space at a minimum abstract, symbolic. The space, although opened, has the “Privacy” proper to the singular, to the unrequited space that belongs to a single person. The spaciousness conditioned by the dimensions of the body for the purposes of constraint is a distinctive category, formally defined by the couple container- content. The more than enough unlimited space of Little Prince and the insufficient one of Alice in Wonderland, both tailored by the measure of man, are radical depictions of the corporeal-spatial imaginary which reflects the architectural projection through the prism of inner moods. The House is interpreted as a materialization of one’s personal limitations, a reinterpretation of Heidegger’s Dasein. It is the originating frame the body comes into contact with, in a privileged sensory perception, the tight House whose awareness is amplified by the spatial constraint. Man, as the scale of things, changes his substantiality reported to the architectural environment in Alice in Wonderland, becoming the plot line for the fantastic dimension. Symbolically, he overcomes the measure of the things that may no longer fit him, the world becomes too small - the issue of the contemporary perception in progression. The material room, that is surpassed, is no longer subject to human scale; it does not increase within the meaning of the Modulor, it does not explode or break down; it merely becomes insufficient, limited for the purposes of constraint. The fantastic dimension is given by the visual difference between the frame and the content - Alice grows expanding in a room - in the end, denying the determination of the construction. The House becomes too small to include both the body and its aspirations. Complementary, the architectural space becomes a tactile, haptic frame, where the body becomes overly-sensitive in front of its limits. “Soon her eye fell on a little glass box that was lying under the table: she opened it, and found in it a very small cake, on which the words «EAT ME» were beautifully marked in currants. «Well, I’ll eat it», said Alice, «and if it makes me grow larger, I can reach the key; and if it makes me grow smaller, I can creep under the door: so either way I’ll get into the garden, and I don’t care which happens!»”26 |

| * Ana Maria Crișan is doctor architect, assistant in the Department of Engineering Synthesis, University of Architecture and Urbanism «Ion Mincu», Bucharest.

** Maggie Taylor (born 1961) is a photo-grapher and digital artist, settled in Gai-nesville, Florida, United States. Her specific perspective expressed in photo-montage have strong surrealistic influences developed over a double major in Philosophy (Yale 1983) and Photography (University of Florida 1987). The works can be found in various collec-tions including: The Art Museum, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, The Centre for Creative Photography, Tucson, AZ, The Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, The Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, AL, Musée de la Photographie, Charleroi, Belgium; Museet for Fotokunst, Odense, Denmark, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX, NationsBank, Charlotte, NC, and the Prudential Insurance Company, Newark, NJ, etc. www.maggietaylor.com |

| NOTES:

1. Lewis Carroll - Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan,1865, PDFreeBooks.org. 2. Jean Nouvel, Golden Angel Tower, Prague, 2000. Jean Nouvel, specula-ting the local folklore, embedded the guardian angel image on the building corner facade looking over the river Vltava and Vysehrad ruins. The reproduction depicts the actor Bruno Ganz, the „angel“ of the Wings of Desire movie, by Wim Wenders, 1987. Critically perceived in terms of scale, materials and iconography, the building has proposed the unification of four existing buildings under a large curtain, with a high of 32.5 m. 3. Juhani Pallasmaa - The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. West Sussex: Academy Press; 2nd edition, U.K., 2005. 4. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Effetti del Buon Governo in città, 1338-1339, Sala della Pace, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. 5. Rudolf Arnheim - Arta și percepția vizuală. O psihologie a văzului creator, 2nd edition, translation: Florin Ionescu, Polirom, București, 2011, p. 198. 6. Alberti, Leon Battista - On the Art of Building. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1991. 7. cf. Keele apud Michael John Gorman - STS 102: „Leonardo: Science, Technology, and Art”, Stanford University, accessed: 05.12.2011 - http://leonardodavinci.stanford.edu /submissions/clabaugh/history/leonardo.html 8. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02.03.2012. 9. Hieronymus Bosch, The garden of Earthly delights (Grădina Edenului), sau The Millennium, ulei pe lemn, triptic, 220×389cm, 1503-1504, Muzeul Prado, Madrid. 10. Lewis Carroll - Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1865, PDFreeBooks.org; Carroll, Lewis - Alice în Țara Minunilor, translation: Elisabeta Gălățeanu, illustrations: Mabel Lucie Attwell. București: Editura Tineretului, 1958. 11. Lewis Carroll - What Alice Found There, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1871, PDFreeBooks.org. 12. Lewis Carroll - Through the Looking-Glass, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1871, PDFreeBooks.org. 13. Ilustrations Maggie Taylor for Lewis Carroll‘s Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, author: Lewis Carroll, Modernbook Gallery, Palo Alto, 2008. 14. Antony Estate, Torpoint, Cornwall, PL11 2QA; early 18th century. Peisagistic resort signed by Reginald Pole Carew, Humphry Repton (c. 1790), accessed: 03.02.2012 - http://www.gardensofcornwall.com/outdoor-kids/antony-house-and-garden-p133063 15. Alice in Wonderland, directed: Tim Burton, screenplay: Linda Woolverton, after novels by Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865, and Through the Looking-Glass, 1871, production: Walt Disney Pictures, Roth Films, Team Todd, Zanuck Company, 2010. 16. Le Corbusier - Unité d’habitation, Cité Radieuse - Marseilles, France, 1952. 17. Le Corbusier, Complex Weissenhof, Stuttgart, 1927. 18. MVRDV, Didden Village, Rotterdam, Netherlands, 2002-2006. 19. El Laberinto del Fauno, directed, screenplay: Guillermo del Toro, coproduction: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, in association with: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM; 2006; 20. Alice in Wonderland, director: Jonathan Miller, production: BBC, Jonathan Miller. Screenplay Jonathan Miller, after a Lewis Carroll novel, 1966. 21. Scott Thill - Bright Lights Film Journal, November 2003 | Issue 42, http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/42/alice.php, accessed 01.02.2011; 22. Jonathan Miller, apud Scott Thill, Bright Lights Film Journal, November 2003 | Issue 42, http://brightlightsfilm.com/42/alice.php, accessed: 02.03.2012. 23. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02.03.2012. 24. The irony in the introduction of the book, the Boa snake representation parable, refers to the author’s own experience, respectively youth failed studies in architecture. 25. „The little prince’s home planet is the asteroid B612ˮ- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry - Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02.03.2012. 26. Lewis Carroll - Alice‘s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan,1865, PDFreeBooks.org. Alberti, Leon Battista - On the Art of Building. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press, 1991. Arnheim, Rudolf - Art and Visual percetion. O psycology of creative sight. Translation: Ionescu, Florin. Bucharest; Meridiane Printing House, 1979. Carroll, Lewis - Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan, 1865, PDFreeBooks.org. Carroll, Lewis - Alice în Țara Minunilor. Translation: Gălățeanu Elisabeta, illustrations: Mabel Lucie Attwell. Bucharest: Tineretului printing House, 1958. Carroll, Lewis - What Alice Found There, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan, PDFreeBooks.org, 1871. Carroll, Lewis - Through the Looking-Glass, illustrations: John Tenn, Macmillan, PDFreeBooks.org, 1871. Crișan, Ana Maria - The Anagram of the Imaginary Architecture. Metamorphosis - Revaluing the Time Paradigm in Architecture, Phd thesis, 2012. Pallasmaa, Juhani - The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. West Sussex: Academy Press; 2nd edition, U.K., 2005. Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le Petit Prince, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0300771h.html, accessed: 02.03.2012. Thill, Scott - Bright Lights Film Journal, November 2003 | Issue 42, http://brightlightsfilm.com/ 42/alice.php, accessed: 02.03.2012. |

The great puzzle. 2006, serie: Almost Alice, copyright: Maggie Taylor

A curious feeling. 2006, serie: Almost Alice, copyright: Maggie Taylor

Call the next witness. 2008, serie: Almost Alice, copyright: Maggie Taylor

It’s always tea-time. 2006, serie: Almost Alice, copyright: Maggie Taylor

I’m grown up now. 2006, serie: Almost Alice, copyright: Maggie Taylor