Moise și Aaron sau critica de arhitectură, cu alte cuvinte

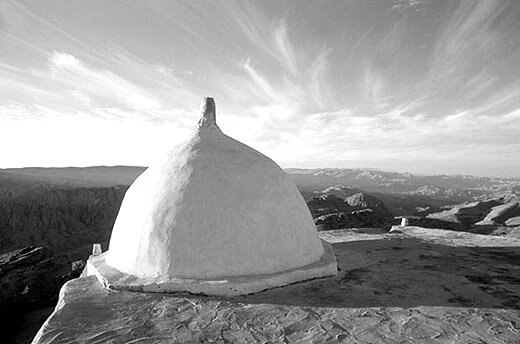

Mormântul lui Aaron

Aaron’s tomb

Moses and Aaron, or architectural criticism with other words

| Global Language of Architecture

În declarația sa de intenții, Bienala1 îndeamnă la o „platformă interactivă între autorități, arhitecți și beneficiari”. Păi, ăsta e un vis minunat, numai că așa va rămâne până când între acești parteneri de nevoie va exista măcar o limbă comună de comunicare, un fel de Global English a arhitecturii. E primul pas pentru ca actualul dialog al surzilor să se transforme într-o negociere constructivă, în ciuda backgroundului educațional și a scopurilor diferite ale părtașilor la acțiune. Arhitectul se află deci la mijloc, singur între două armate puternice de laici - una cu puterea politică, cealaltă cu puterea banului - fiecare cu tot felul de interese, cel puțin străine, dacă nu contrare calității pe care o dorește arhitectul. În plus, datoria primordială a arhitectului e slujirea interesului general al societății - adică un al treilea grup de laici implicați. Interesele arhitectului și ale publicului ar trebui să coincidă, numai că masiv, inerțial, heterogen și dezorientat, inocentul public e la fel de străin de valorile arhitectului ca și ceilalți doi. Teza mea e că n-avem totuși nicio șansă la nicio platformă interactivă cu oficialii și cu finanțatorii dacă nu ne facem din public un aliat. Dacă nu-i recâștigăm măcar o parte din simpatia și respectul de altădată. Dacă nu ne reabilităm în ochii lui. Putem reînvia vechea lui prețuire pentru artiști, dar mai putem profita și de slăbiciunea publicului față de cei slabi ca și el, în fața puterii oficiale și a puterii banilor. Din nevoia unei bune relații cu publicul a fost creat cândva, dar nu foarte de mult, un instrument democratic numit critică, pe care arhitectura și-a asociat-o în lupta contra necunoașterii și a intereselor potrivnice. A fost creat așa cum Moise, conștient de incapacitatea lui de bun comunicator și l-a creat pe Aaron, fratele lui, drept purtător de cuvânt în fața unei mase de evrei nefericiți și dezorientați și ei. Mișcarea a fost extrem de inteligentă și mulți profeți eroici și-ar fi salvat gâtul dacă ar fi avut această abilitate strategică - de la Grahi, trecând prin Savonarola și Thomas Műnzer, până la Ludovic al XVI-lea și Nicolai al II-lea. În 1754, Blondel a conștientizat și el problema și a susținut într-un discurs că prelegerile de la Academia sa sunt concepute în așa fel încât să poată fi urmărite și de laici. Pentru că - a explicat Blondel - „dacă arhitecții s-ar fi explicat permanent față de public pentru ceea ce produceau, n-ar mai fi nevoie astăzi de atâtea eforturi pentru a scuza lipsa puterii de judecată a oamenilor în fața arhitecturii”. Poate însă că momentul-cheie în care s-a născut critica de arhitectură a fost anul 1747 când, la Salonul Artelor de la Paris, un gânditor al artelor numit Etienne La Font de Saint-Yenne a invitat pe toată lumea, de orice profesie, să comenteze exponatele și „prin judecata sa să poată schimba evoluția faptelor”. Cert este deci că abia în secolul al XVIII-lea a fost arhitectura „iluminată” de înțelepciunea lui Moise. De ce nu s-a născut ea, critica, mai de mult, odată cu teoria, de exemplu? Pentru că abia în iluminism a apărut presa scrisă - instrument al democrației care a permis intrarea în joc a publicului. Deci critica s-a născut legată de public. De atunci, jurnalele au găzduit dezbateri libere despre arte și arhitectură. Iar ideile diseminate au atras o arie lărgită de comentatori interesați. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 6/2012 al revistei Arhitectura. |

| 1. Reproducem comunicarea pregătită de autoare pentru Bienala Națională de Arhitectură București 2012, dar care, dintr-o încurcătură, n-a mai fost prezentată (n.r.). |

| A Global Language of ArchitectureIn its declaration of intent, the Biennale1 advocates an “interactive platform between the authorities, architects and beneficiaries”. This is a wonderful dream, but it will remain just that, a dream, until a common language exists between these partners by necessity, a kind of global English of architecture. This will be the first step towards transforming the current dialogue between the deaf into a constructive negotiation, despite the differing educational backgrounds and aims of the separate parties in the process.

The architect is therefore caught in the middle, alone between two powerful armies of laymen - political power on the one hand and the power of money on the other - each with all kinds of interests that are at best alien, if not downright opposed, to the quality desired by the architect. In addition, the architect’s primordial duty is to serve the general interest of society, i.e. a third group of involved laymen. The interests of the architect ought to coincide with those of the public, but the massy, inert, heterogeneous, disoriented and innocent public is just as alien to the architect’s values as the other two. My theory is that we will have chance on any interactive platform with officials and sponsors unless we make the public an ally. Unless we win back at least a part of the public’s erstwhile sympathy and respect. Unless we rehabilitate ourselves in the public’s eyes. We can revive the public’s former esteem for artists, but we can also profit from the public’s sympathy towards those who are similarly helpless in the fact of official power and the power of money. Not very long ago, out of a need for good relations with the public, a democratic tool known as criticism was created, which architecture has taken up in its struggle against ignorance and hostile interests. It was created in the same way as Moses, aware of his lack of skill as a good communicator, made Aaron, his brother, his spokesman before the disgruntled and disoriented mass of the Jewish people. It was an extremely shrewd move and many heroic prophets would have saved their own necks if they had had the same strategic ability, from the Grachi to Savonarola, Thomas Münzer, Ludovic XVI and Nicholas II. In 1754, Blondel became aware of the problem and argued in a speech that the elections at his Academy were conceived in such a way as to allow laymen to follow them. For, explained Blondel, “if architects had always explained to the public what they built, there would not be any need of so many efforts today to pardon people’s lack of judgement in architectural matters”. But perhaps the key moment in the emergence of architectural criticism occurred in the year 1747, when at the Salon of Arts in Paris a thinker named Etienne La Font de Saint-Yenne invited people of all professions to comment on the exhibits and “by their judgement to be capable of changing the evolution of events”. What is certain is that it was not until the eighteenth century that architecture was “enlightened” by the wisdom of Moses. Why did criticism not emerge longer ago, at the same time as theory, for example? The reason is that it was not until the Enlightenment that newspapers appeared, a tool of democracy that allowed the public to enter the fray. The birth of criticism is therefore connected to the public. Ever since, newspapers have been home to free debate about art and architecture. And the ideas they have disseminated have attracted a wider field of interested commentators. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| 1. Wereproduce the communiqué the author prepared for the 2012 Bucharest National Biennale of Architecture, but which, due to a mix-up, was not issued (editor’s note). |