Ispita caselor posibile - Interviu cu arhitectul Șerban Sturdza

The Temptation of Possible Houses

An interview with architect Șerban Sturdza

| Despre relația proiect-șantier-clădire realizată și aportul de creativitate al șantierului în cadrul acesteia |

| Interviu cu arhitectul Șerban Sturdza realizat de Adrian Bălteanu, în luna februarie 2015 |

| Adrian Bălteanu: Pentru început, vă rog să ne spuneți câteva cuvinte despre posibilele relații între proiect, șantier și clădirea realizată?

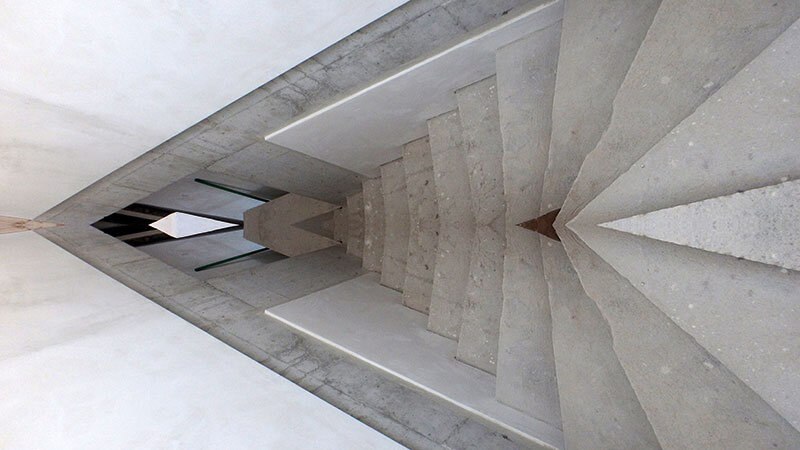

Șerban Sturdza: Un capitol sunt planșele, memoriul, avizele care fac parte dintr-o documentație și un altul sunt realitatea fizică, dorințele, posibilitățile, conflictele care deformează, într-o măsură mai mare sau mai mică, realitatea prestabilită. Există o diferență, o abatere și o suprapunere, mai mare sau mai mică, față de documentele inițiale, diferență care, bineînțeles, se încadrează în lege, pentru că există corecții pe parcursul șantierului prin note de constatare, note de șantier, acte administrative adiționale ș.a.m.d. Probabil că orice arhitect va putea explica, stând în fața unei case făcute de el, cât de mare este diferența față de proiectul inițial și cât de multe frustrări a trebuit să parcurgă în perioada în care proiectul a devenit realitate. În această perspectivă, există un anumit mod de a te comporta pe șantier mai puțin liber sau mai liber. Cred că, în cazul meu, șansa, pe care o consider foarte mare, a fost că am avut câteva proiecte destul de importante în perioada de dinainte de 1990, în care libertatea pe care o aveam era mare. Este un paradox. Șantierul era al statului și mai puțin controlabil decât ceea ce se face astăzi într-un șantier fie al unui stat ceva mai structurat după niște reguli capitaliste, fie al unui comanditar privat care își urmărește atent lucrările. Șansa mea a fost că am avut câteva șantiere care au durat foarte mult, părerile erau foarte împărțite, claritatea temei era discutabilă. Atunci mi-am luat libertatea să încerc să văd dacă pot să proiectez anumite porțiuni, nu chestiuni mari, detalii, fără să desenez. Adică să proiectez cam cum face un sculptor sau un pictor care se gândește, își face câteva scheme, după care improvizează. Faptul de a improviza arhitectură, volume e un lucru care cred că ar fi foarte normal, dar nu stă în logica a ceea ce înseamnă proiectare, începând din Renaștere și până acum. A face un proiect care are o anumită structurare și a-l transpune în realitate este regula normală, iar a sta în fața unui spațiu liber și a spune „fă un zid acolo, mai urcă așa, hai să punem și aici un perete, facem golul aici, revin după ce mă mai gândesc, mai dă jos în partea cealaltă” nu stau în firea lucrurilor. Dacă spui: „Aici ar fi bine să fie așa. Ce părere ai, tu, domnule zidar, despre chestia asta? Știi să o faci?”, iar el zice: „Păi, să încerc”, și se încearcă la fața locului, este un exercițiu complicat. Te pune într-o situație dificilă: cum hotărăști pe loc ceva atât de important, fără să ai gumă, creion, foiță sau calculator. Pe de altă parte, îți dă o satisfacție enormă pentru că vezi cum se nasc lucrurile fără ca desenul și proiectul să se interpună între gândul tău și realitate. Concluzia la care am ajuns nu este că unul dintre modurile de a acționa este mai bun decât celălalt, ci că ies lucrurile diferit, cu toate că ești același om. În sensul că un spațiu care este proiectat anterior e un spațiu rațional, simplificat și care are la bază un punct de pornire și o destinație, iar într-unul improvizat și care nu are un sistem pe care ți-l dă desenul planului, elevațiile, secțiunile, mintea este condusă de succesiunea și de seducția gestului imediat anterior. Atunci spațiul se naște din aproape în aproape, organic, cu justificări de alt tip. Nu discut dacă este mai bine sau mai rău, pentru că nu îmi dau seama, dar iese altceva. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 1 / 2015 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| On the relationship between design, site and constructed building and the site’s contribution thereto in terms of creativity |

| An interview with architect Șerban Sturdza conducted by Adrian Bălteanu, in February 2015 |

| Adrian Bălteanu: To start with, please tell us a few words on the possible relationships between the design, the building site and the actual building

Șerban Sturdza: On the one hand you have the drawing boards, the memorandum, the endorsements which are part of the documentation, and on the other hand, you have the actual reality, the desires, possibilities and conflicts which distort the pre-established facts to a larger or smaller extent. There is difference and deviation from, as well as a larger or smaller overlapping with the original documents, which difference must at all times comply with legal regulations, because corrections are constantly brought throughout the works via observation notes, building site notes, administrative addenda, and so on. Any architect standing in front of one of the buildings designed by him will probably tell you about the considerable difference between the original and the final design, and the frustrations he had to put up with during the process of materialization. From this perspective, there is a certain way of acting on the building site, more or less freely. I was fortunate enough to handle several quite important projects before 1990, in the context of which I enjoyed a lot of freedom. There is a paradox here. The building site was owned by the state and was less controllable than any building site nowadays, whether it is publicly owned by a state more closely structured by a number of capitalistic rules or privately owned by an entrepreneur who carefully monitors the works. It was my luck to be in charge of several building sites which lasted for a long time; the opinions were divided, the clarity of the brief was questionable. Then I took the liberty to see whether I was able to design several portions, details, without drawing first, i.e. to design more in the manner of a sculptor or painter who thinks, outlines a few sketches, then improvises. To improvise architecture and volumes would be fairly normal, in my opinion, but the truth is that it is not in keeping with the logic of design, as such term has been understood from the Renaissance until present. The usual rule is to create a design with a specific structure and to transpose it in reality; to stand in front of a vacant space and say “build a wall there, go up a little, let’s put a wall here as well and a gap here...no, we’ll put the gap here after I think it over a little more, let’s rather take from the other side a little” is not in compliance with the logic of things. If you say: “Here it had better be this way. What do you think about this, master stonemason? Do you know how to build it?”, and he says “Well, let me try”, and actually he tries it on site. This may turn out to be a strenuous exercise. It puts you in a difficult situation: how do you make such important decisions on the spot, without pen, drafting paper, rubber or calculator? On the other hand, it is enourmously satisfying to see things materialize without having the drawing and the design interfere between your thought and reality. The conclusion I have arrived at is not that one way of doing it is better than the other, but that things come out differently depending on the method, although you are still the same person. Basically, a space designed in advance is a rational, simplified space, relying on a starting point and a destination, while with an improvised space which does not benefit from a system consisting of layout, elevations, sections, the mind is led by the succession and the seduction of the immediately preceding gesture. Then the space comes to life step by step, organically, with a different justification. I cannot state for sure whether it is better or worse, but it is something else. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |