Le Corbusier și arhitectura în România | Le Corbusier and Architecture in Romania

| Charles-Édouard Jeanneret ajunge la București – venind de la Giurgiu – în seara lui 16 iunie 1911. Este însoțit de prietenul său, August Klipstein, care poate fi considerat „cauza” sosirii la București. La începutul primăverii 1911, Charles-Édouard lucrează în biroul lui Peter Behrens – la Berlin Neubabelsberg – unde, contrar legendei, nu i-a întâlnit nici pe Walter Gropius, nici pe Mies van der Rohe, care terminaseră deja stagiul. Este nemulțumit de situația sa: „Patronul nu plătește... Autocrat teribil, regim de terorism... Este o vastă exploatare...”. În același timp, recunoaște: „...Este totuși un tip. Pe care îl admir, de altfel”1. Pe un alt plan, progresele în germană nu sunt pe măsura așteptărilor, iar nivelul artelor în Austria și Germania – unde își petrecuse deja luni de zile – i se pare inferior „Geniului latin” și capitalei acestuia, Parisul, unde lucrase la frații Perret, între jumătatea lui iunie 1908 și noiembrie 1909.Știm că între 1907 și părăsirea biroului Behrens (sfătuit și ajutat de profesorul său de la Școala de Arte din La Chaux-de-Fonds, Charles l’Eplattenier), Charles-Édouard vizitează nordul Italiei, Roma, Budapesta, Viena, Londra, Parisul, Germania (în lung și în lat).

Șansa și relațiile îi permiseseră să aibă deja la activ realizarea (împreună cu arhitectul René Chapallaz) vilelor: Fallet, Stotzer și Jaquemet, pentru care își încasase onorariile. La 23 de ani, venise momentul să-și încheie perioada de formare, pentru a păși „cu dreptul” în cariera de arhitect. Se conturează astfel proiectul a ceea ce se va numi „Le voyage d’Orient”: coborârea Dunării cu vaporul, Bulgaria, Grecia (cu obiectiv principal Acropola Atenei), Istanbul și urcarea „cizmei” italiene pentru a se întoarce în Elveția. Să-l lăsăm să ne explice: „Mă mângâiam de mult cu acest vis... Prietenul Klipstein își făcea doctoratul în Filosofia artei cu teză despre primitivii spanioli. Zece tablouri de El Greco la Curtea Regală a României. Pentru că trebuie să meargă la București, de ce nu și la Istanbul. Atunci, în ianuarie, i-am răspuns da și am început să pregătim călătoria”2. În realitate, „pregătirea călătoriei” începuse mai devreme, grație unei alte prietenii, cea cu Ritter. William Ritter – fiul unui înstărit inginer de origine alsaciană, trăind la Neuchâtel – era considerat, la începutul secolului, un scriitor și un critic de artă important. Este cel care – pe un bun fond – a făcut din Charles-Édouard Jeanneret „scriitor”: în jur de patruzeci de cărți și o sută de articole scrise în cursul vieții. Invitat de bibliotecarul Casei Regale române (elvețianul Léo Bachelin) la București, în 1890, Ritter „este prins de o dublă pasiune pentru poporul român, în toate manifestările culturale și folclorice (arte decorative, arhitectură vernaculară, costume, tradiții, povești și legende etc.)...”3. Este prieten cu Nicolae Grigorescu, cu Alexandru Vlahuță și cu Ion Luca Caragiale și nu va ezita să-l recomande pe Charles-Édouard acestora. Iată contextul Să-l lăsăm pe tânărul voiajor să ne relateze impresiile: „Bucureștiul este un oraș foarte monden, foarte interesant datorită splendidelor toalete pe care le vezi. Căldura este, de două zile, formidabilă...”4. Deja excelent comunicator, Charles-Édouard se angajase să trimită o serie de corespondențe de voiaj gazetei locale din La Chaux-de-Fonds. Bucureștiul are dreptul la un articol aparte („Vers l’Orient. Bucarest”, „Feuille d’Avis de La Chaux-de-Fonds”, din 19 octombrie 1911), intitulat „Lettre à une dame qui me dit un jour son admiration pour Carmen Sylva, reine de Roumanie”. După ce face un portret măgulitor reginei-poetă, el se scuză că va trebui să demoleze idolul doamnei căreia îi adresează scrisoarea. Cauza: vizitarea Castelului Peleș (unde se găseau tablourile lui El Greco) pe care îl consideră „foarte urât”, într-o dezordine remarcabilă și cu un al patrulea El Greco fals... Alt punct de vedere, însă, când vorbește de București: „Bucureștiul este plin de Paris; mai mult decât atât. Femeile, sub lumina teribilă, se fardează, sunt frumoase și îmbrăcate în toalete rafinate. Ele nu vă par străine, cu ținute bizare care ar crea ele însele o barieră. În trăsurile ce revin de la plimbare, în această lungă defilare pe Calea Victoriei, ele șed alungite leneș și toaletele lor de la Paris, din stofe somptuoase sobre, marile pălării negre, gri sau albastre agitate de o enormă pană – sau, de asemenea, micile toci pe părul invadator – fardul ochilor sau al gurii, pe un ten palid, formele mobile ale frumoaselor corpuri mângâiate de stofe – totul ne îndeamnă să le admirăm... și să ne amintim, cu aceeași melancolie, cuceritoarele viziuni ale Parisului șic”. În 1911, Jeanneret nu este încă militantul cu verbul tăios. Ochii îi sunt, însă, bine deschiși. El își încheie articolul: „Ce să vă spun despre acest oraș plin de arbori, care se întinde departe, dar oferind tot timpul aspectul închis al unui cartier de «petits-maîtres»? Etajele nu depășesc pe al doilea și străzile se închid repede”5. În drum spre Peleș, vizitează casa lui Nicolae Grigorescu la Câmpina, este primit de Mitropolitul Ghenadie la Mănăstirea Căldărușani, schițează și comentează planul reședinței, face câteva crochiuri și fotografii. În același timp, dă impresia că asociază ce a văzut în cele patru zile efective de vizită, mai degrabă, Occidentului. Balcanii și Orientul încep cu Bulgaria, cu nenumăratele desene și impresii consemnate în carnete. Ceea ce nu este decât adevărat. În corespondența trimisă ulterior de la Istanbul sau din Grecia există câteva foarte scurte referiri la România, dar nimic complementar celor de mai sus. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 6 / 2015 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| Note:

1 Rémi Baudouï, Arnaud Dercelles (ed.), Le Corbusier. Correspondance, Tome I, Lettres à la famille 1900-1925, InFOLIO éditions, 2011, pag. 329, 330. 2 Ibidem, pag. 359. 3 Marie-Jeanne Dumont (ed.), Le Corbusier, W. Ritter, Correspondance croisée 1910-1955, Paris: Éditions du Linteau, 2014, pag. 15. 4 Rémi Baudouï, Arnaud Dercelles (ed.), op. cit., pag. 373. 5 Philippe Duboy (ed.), Le Corbusier. Croquis de voyages et études, Paris: La Quinzaine Littéraire/ Louis Vuitton, 2009, pag. 74, 76. |

| Charles-Édouard Jeanneret arrived in Bucharest – coming from Giurgiu – on the evening of June the 16th, 1911. He was accompanied by his friend, August Klipstein, who may be considered the “cause” for his arrival in Bucharest. In the early spring of 1911, Charles-Édouard was working in the office of Peter Behrens – in Berlin Neubabelsberg – where, contrary to the legend, he did not meet either Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe, as they had already completed their traineeship. He was unhappy with his status: “The employer does not pay... He’s a terrible autocrat; this is a regime of terror... Sheer exploitation...” At the same time, he admitted: “... However, there is this man whom I totally admire”.1 On another scale, his knowledge of German was not advancing according to expectations, and he found the practice of arts in Austria and Germany, where he had spent several months already, to be inferior to that of the “the Latin Genius” and its capital, Paris, where he had worked with the Perret brothers, between half-June, 1908 and November, 1909.It is known that between 1907 and his leaving the Behrens office (advised and aided by Charles l’Eplattenier, his professor at the Art School in La Chaux-de-Fonds), Charles-Édouard visited northern Italy, Rome, Budapest, Vienna, London, Paris and Germany (far and wide).

His luck and relations had allowed him to already build (along with architect René Chapallaz) the Fallet, Stotzer and Jaquemet villas, for which he had also cashed his fees. At the age of 23, it was time to put an end to his traineeship and to fully embrace his career as an architect. Thus took shape the project of what was to be called “Le voyage d’Orient”: going down the Danube on a steamship, through Bulgaria, Greece (with Acropolis of Athens as main objective), and Istanbul and then up the Italian “boot” to return to Switzerland. In his own words: “I had been cherishing this dream for a long time... My friend Klipstein was taking his PhD degree in Art Philosophy with a thesis on Spanish primitives. Ten paintings by El Greco at the Royal Court of Romania. He had to go to Bucharest, why not Istanbul as well. Then, in January, I told him yes and we began to plan the trip”.2 In reality, the preparations for the trip had begun earlier, thanks to another friendship, with Ritter. At the beginning of the century, William Ritter – the son of a prosperous engineer of Alsatian origin, who lived in Neuchâtel – was considered an important writer and art critic. He was the one who, while benefitting from good input, managed to turn Charles-Édouard Jeanneret into a “writer”: around forty books and one hundred articles written during his lifetime. As a guest of the librarian of the Romanian Royal House (the Swiss Léo Bachelin) in Bucharest, in 1890, Ritter “became extremely fond of the Romanian people, in all its cultural and folklore manifestations (decorative arts, vernacular architecture, costumes, traditions, stories and legends etc.)...”.3 He was a friend of Nicolae Grigorescu, Alexandru Vlahuță and Ion Luca Caragiale and would readily recommend Charles-Édouard to them. Here is the context Let us discover the impressions of the young voyager himself: “Bucharest is a very fashionable, very interesting city, thanks to the wonderful outfits one can see. The heat has been formidable in the past two days...” 4 An excellent communicator already, Charles-Édouard had undertaken to dispatch a number of voyage letters to the local gazette in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Bucharest was entitled to a separate article (“Vers l’Orient. Bucarest”, “Feuille d’Avis de La Chaux-de-Fonds“, dated October the 19th, 1911), entitled “Lettre à une dame qui me dit un jour son admiration pour Carmen Sylva, reine de Roumanie” (Letter to a lady who once confessed to me her admiration for Carmen Sylva, queen of Romania). After a flattering portrait of the queen-poetess, he apologized for having to demolish the idol of the lady to whom the letter was addressed. The reason: he had visited the Peleș Castle (hosting paintings by El Greco), which he found “very ugly”, in remarkable disorder and possessing a fourth fake El Greco... His standpoint was altogether different when it came to Bucharest: “Bucharest is as filled with Paris as can be, and more. Under the terrible light, the beautiful women put on make-up and dress in refined gowns. They do not appear foreign to one, or wearing strange costumes which might in themselves constitute a barrier. They lie idly, returning from their stroll, in carriages which form a long line on Calea Victoriei, and their costumes from Paris, made of elegant sumptuous wool, their large black, grey or blue hats stirred by an enormous feather – also their small toques on their thick rebellious locks –, the make-up on their eyelids or mouth, on a pale complexion, the mobile forms of their beautiful bodies caressed by woollen fabrics – everything urges us to admire them, and to recall, with the same nostalgia, the charming visions of a chic Paris…” In 1911, Jeanneret still wasn’t the militant brandishing a sharp verb. His eyes were, nevertheless, wide open. This is how he ended his article: “What can I tell you about this city full of trees, which spreads far and away, while offering the viewer on a permanent basis the closed appearance of a district of «petits-maîtres»? The buildings do not boast more than two floors, and the streets end quite abruptly”. 5 On his way towards Peleș, he visited Nicolae Grigorescu’s house in Câmpina, was received by Metropolitan Bishop Ghenadie of Căldărușani Monastery, sketched and commented the plan of the residence, drew a couple of sketches and took several photographs. At the same time, he gave the impression that he was associating what he saw in his four days of visit with the West. The Balkans and the Orient began with Bulgaria, with the innumerable drawings and impressions noted down in his notebooks. And this was very true. In the correspondence subsequently sent from Istanbul or Greece, there are several very brief references to Romania, but nothing in addition to the above. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |

| Notes:

1 Rémi Baudouï, Arnaud Dercelles (ed.), Le Corbusier. Correspondance, Tome I, Lettres à la famille 1900-1925, InFOLIO éditions, 2011, pp. 329, 330. 2 Ibidem, p. 359. 3 Marie-Jeanne Dumont (ed.), Le Corbusier, W. Ritter, Correspondance croisée 1910-1955, Paris: Éditions du Linteau, 2014, p. 15. 4 Rémi Baudouï, Arnaud Dercelles (ed.), op.cit, p. 373. 5 Philippe Duboy (ed.), Le Corbusier. Croquis de voyages et études, Paris: La Quinzaine Littéraire/ Louis Vuitton, 2009, pp. 74, 76. |

Horia Creangă, Imobil Malaxa-Burileanu/ Malaxa-Burileanu Building, București (1935-1937) © Arhiva fotografică a UAR

G. M. Cantacuzino, Vilă pentru prințul George Valentin Bibescu/ Prince Bibescu Villa, Eforie Nord (1931) © Editura Simetria, București

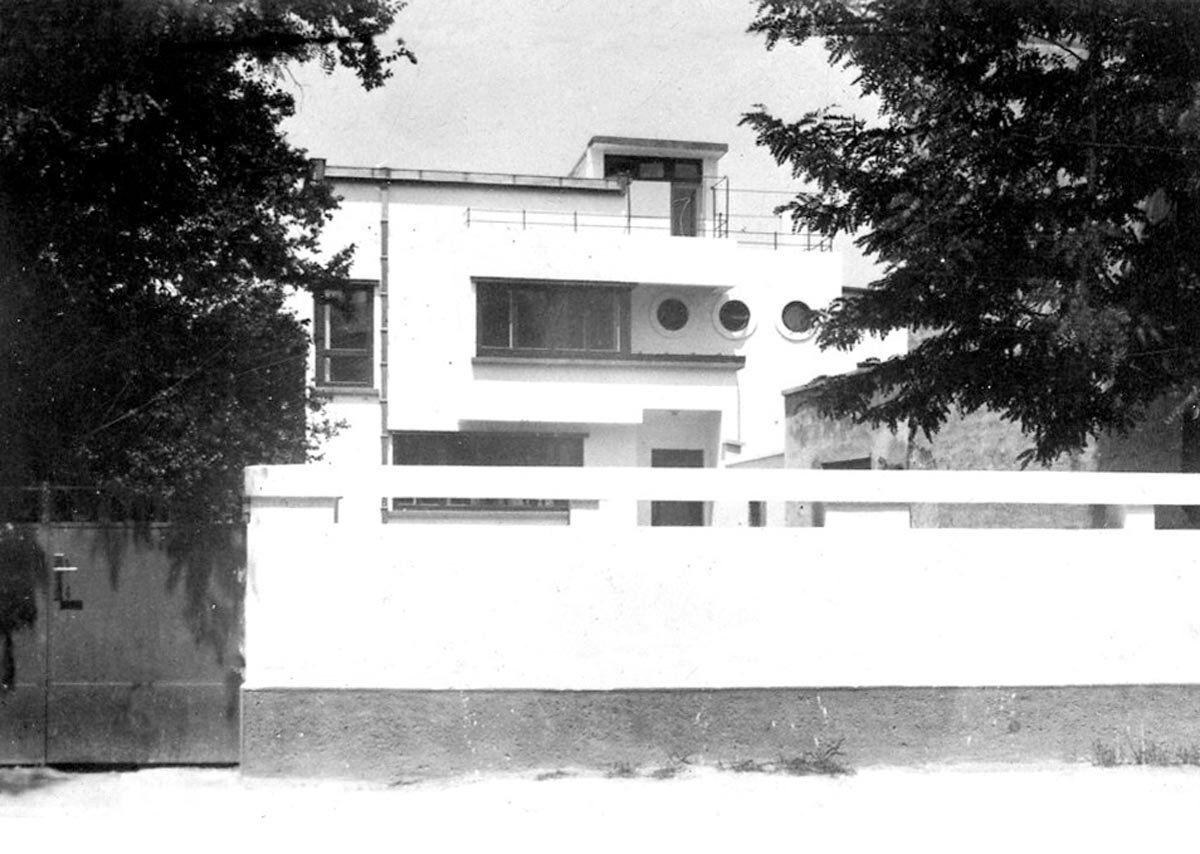

Marcel Iancu, Vila Fuchs/ Fuchs Villa, București (1927) © Editura Simetria, București

Horia Creangă, Imobilul Elena Ottulescu/ Ottulescu Building, București (1934-1945) © Gheorghe Dumitru, UAR, 1992

Cezar Lăzărescu, Lucian Popovici, N. Stopler și colectiv, Restaurantul „Perla Mării”/ „Perla Mării” Restaurant, Eforie Nord (1958) © Arhiva fotografică a UAR