El Laberinto del Fauno. Arhitectura, între pierdere temporală și manipulare spațială

5 Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,

Berlin, 2003-2004

©Fotografii: Vlad Eftenie

El Laberinto del Fauno

Architecture in-Between Temporal Loss and Spatial Handling

| „Cu mult timp în urmă, pe tărâmul subteran unde nu există minciuni sau durere, trăia o prințesă care a visat lumea umană. A visat cerul albastru, briza blândă și soarele strălucitor. Într-o zi, înșelându-și temnicerii, Prințesa a scăpat. Odată ajunsă afară, strălucirea a orbit-o și i-a șters orice amintire din memorie. A uitat cine era și de unde venea. Suferea de frig, boală și durere. În cele din urmă a murit. Cu toate acestea, tatăl ei, regele, a știut întotdeauna că sufletul Prințesei va reveni, poate în alt corp, în alt loc sau în alt timp. Și el va fi continuat să o aștepte până când și-a tras ultima suflare, până când lumea a încetat să se învârtească.”1

(Guillermo del Toro/ Pan, El Laberinto del Fauno) |

| Introducerea din pelicula cinematografică El Laberinto del Fauno2 anticipează drumul fetiței Ofelia, pierdută în realitate. Spațiul-cheie introdus de regizorul și scenaristul Guillermo del Toro este labirintul faunului - punctul de confluență al realității Italiei lui Franco cu o lume magică originară.

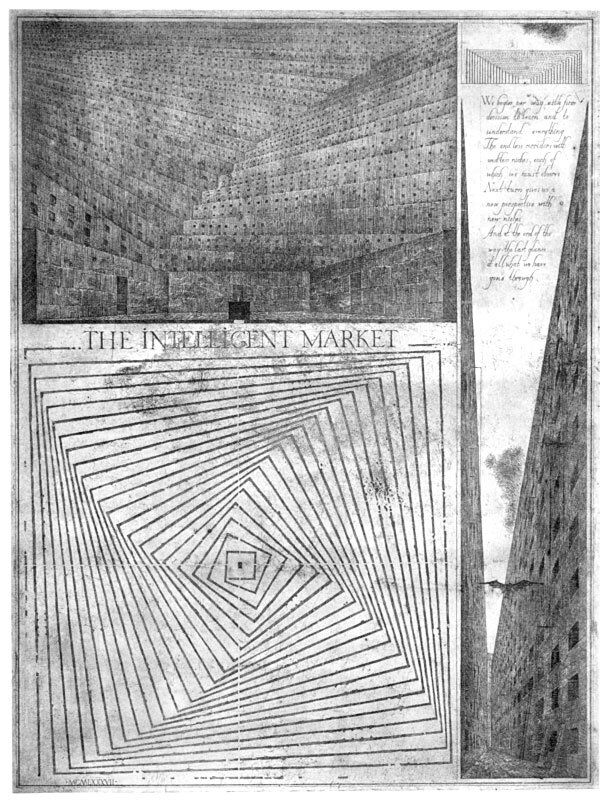

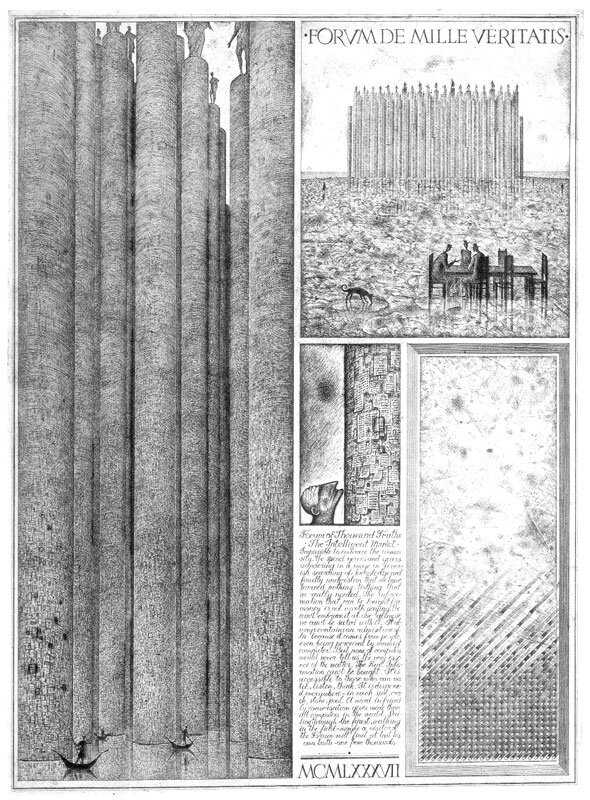

Paradoxal, angoasele perioadei istorice (premergătoare celui de-al Doilea Război Mondial3) determină o fractură a poveștii, dezvoltată de regizor în două planuri - pe de o parte realitatea luptelor de gherilă, și pe de alta fantastica lume reimaginată de copii. Cele două planuri se întâlnesc în punctul nodal al labirintului - acces într-o altă unitate temporală, loc al inițierii, descoperirilor, al trecerii, reîntoarcerii într-o lume pură a poveștilor, o lume a timpului pierdut „fără minciuni, fără durere”. Remarcabilă este abilitatea de a introduce entitatea labirintică, pe o frecvență care reunește percepțiile arhitecturale ale elementului. Guillermo del Toro compune un sistem concentric, recurent, cuplând două dintre formele tipice, referențiale ale labirintului4 - construiește o lume edificată ierarhic în straturi succesive. La nivelul solului, intriga spațială se desfășoară în grădină, amintind de circuitele vegetale romantice, respectiv în subteran, reluând tipologia originară a labirintului/maze, circuit planimetric. Poveștile reiau frecvent tipologia grădinilor dezvoltând modelul pădurilor sacre, fermecate, în mijlocul cărora regăsim templul sau urmele unei arhitecturi în ruină, mistuită de vegetație. Deseori asociate în amenajările peisajiste ale secolelor XV-XIX, labirintul și fântâna sunt, în fanteziile cinematografice, părți ale aceluiași sistem metaforic. Mizând pe complexitatea sistemului constructiv - scări, pereți, stâlpi - labirintul exploatează spațialitatea orizontală atât la nivelul solului, în El Laberinto del Fauno, cât și în subteran, în Interview with a Vampire5. Tipologia fântânii (puțul) dezvoltă axul vertical al descen- siunii-ascensiunii - speculează puritatea formei săpate ad invertum și forța centrului, ipostaza simbolică a arhitecturii subpământene ca acces punctual într-o altă lume. „Labirintul este un semn foarte, foarte puternic” - „este un simbol primordial, aproape iconic. Din punct de vedere cultural, poate însemna atât de multe lucruri, în funcție de aria de interpretare. Dar principalul lucru pentru mine este faptul că, spre deosebire de un labirint vegetal, labirintul reprezintă, în fapt, o trecere continuă spre a găsi, și nu de a te pierde. Este vorba despre găsirea, nu pierderea drumului tău. Acest lucru a fost foarte important pentru mine.”6 Peter Zumthor materializează labirintul în termenii parcursului și struc-turii introvertite. Metafora regăsirii stă la baza proiectului Serpentine Gallery Pavilion7 - Grădina ascunsă (hortus conclusus) sub cota coroanelor arborilor din Grădinile Kensington în Londra, este aparent un volum paralelipipedic, opac, scund, concentrând metaforic lumina și vegetația în atriumul central. În interpretarea cromatică, centrul este pozitiv, luminos, dominant spațial, antitetic construcției propriu-zise - o incintă, telurică, gravitațională, lestată de cromatica închisă și deschiderile minimale. „Conceptul este hortus conclusus, o cameră contemplativă, o grădină într-o grădină. Clădirea acționează ca o scenă, un fundal pentru grădina interioară de flori și lumină. Prin întuneric și umbră se intră în clădire de pe peluză și se începe tranziția către grădina centrală, un loc retras/sustras din lumea zgomotului, traficului și mirosurilor londoneze - un spațiu interior, în care poți să stai, să te plimbi, să contempli florile. Această experiență va fi intensă și memorabilă, asemeni materialelor - ele însele pline de memorie și timp.”8 Construcția este o grădină în grădină, o lume în altă lume, în aceeași manieră în care își proiecta și Umberto Eco labirintul9. În spiritul teoriilor postmoderniste (Il Nome della Rosa), Eco susține ciclicitatea poveștilor și raportarea acestora la alte povești, în întreg sau parte: „cărțile vorbesc întotdeauna despre alte cărți și fiecare poveste spune o alta, care deja a fost spusă” - o recurență pe care o aplică și construcției arhitecturale. Similar, pentru Jorge Luis Borges, universul din Library of Babel este descris ca o bilbiotecă infinită, adăpostind nesfârșite camere simetrice, conținând același număr de cărți, conținând același număr de simboluri10. Anticipând jocurile contemporane, arhitecții de hârtie Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin reinterpretau și transpuneau geometria labirintică concentrică prin multiplicarea incintelor, compunând, în lucrarea grafică The Intelligent Market, o structură aparent în continuă creștere prin autogenerare celulară - gravură, Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition, 1987. Dintr-o perspectivă complementară, teoreticianul Gilles Deleuze sublinia interpretarea planurilor succesive: „Exteriorul nu este o limită fixă, ci un subiect în mișcare animat de mișcările peristaltice, falduri și pliuri care alcătuiesc împreună un interior: nu sunt nimic altceva decât exteriorul, chiar interiorul exteriorului”11. Într-un gest de compresie materială, Peter Zumthor înghesuia pavilionul din Grădinile Kensington în grosimea pereților perimetrali, minimalizând lățimea structurii edificate și amplificând proporția centrului-grădină. Analog structurilor lui Umberto Eco, rezolvarea înclină către tipologia labirintică prin perspectivele obturate, introducerea fragmentată a luminii, cromatica obscură, traseul ciclic-concentric, raportat continuu la un centru, oferind frustrantele perspective similare. Drumul este identificat ca factor prim structurant spațial, elementele constructive subordonându-se parcursului, traseului. Pereții în context devin limită, remarcându-se, în primul rând, ca planuri direcționante. „Ne vom începe drumul cu decizia fermă de a învăța și de a înțelege totul. Coridoarele nesfârșite cu nișe fără sfârșit, pe care trebuie să le respectăm pe fiecare în parte. Rândul următor ne oferă o nouă perspectivă cu noi nișe. Și la sfârșitul drumului - ultima privire a întregului parcurs.”12 (Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin) Revenind asupra labirintului din El Laberinto del Fauno, remarcăm relevanța drumului în sensul finalității. Grădina este proiectată integrând labirintul ca spațiu ritualic și de sacrificiu, pe baza componentelor religioase/astrologice13, este cadrul central al corespondenței dintre lumea pământeană și cea subterană. Ofelia parcurge labirintul terestru, edificat volumetric, găsește puțul central, coboară și, în ultimul stadiu al descoperirii, se confruntă cu un „maze” planimetric14 incizat în piatră. Regizorul speculează semnificația descensiunii asociind tipologiile arhitecturilor subterane cu modelul columbarium și semnificația necropolelor, reunindu-le stilistic. Împlinirea spirituală, maturizarea15, conștientizarea eului ca finalitate a testelor sunt cheia drumului din El Laberinto del Fauno; nefinalizarea labirintului, abandonarea drumului, implică pierderea sensibilității, a inocenței copilăriei. „Spiritul tău va rămâne de-a pururi printre oameni. Vei îmbătrâni asemeni lor, vei muri asemeni lor. Și toate amintirile cu privire la tine vor păli în timp. Iar noi ne vom duce odată cu acestea.”16 (Faunul în discuție cu Ofelia, El Laberinto del Fauno) Despre pierdere, spirit și timp, în termenii labirintului spațial vorbesc monumentele dedicate Holocaustului proiectate de Peter Eisenman și Daniel Libeskind la Berlin: Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, 2003-2004, și respectiv Garden of Exile and Emigration, Jewish Museum, 1999. Reactualizarea modelelor labirintice-grădină, ca spații monumental arhitecturale, se realizează în interpretarea contemporană ca structură matricial-labirintică prin uniformitate (Daniel Libeskind), multiplicare stroboscopică a volumelor paralelipipedice - covor-cimitir alcătuit din pietre de mormânt17 (Eisenman) - sau câmp acoperit de fragmente colțuroase la Treblinka (Haupt & Dyszenko). „Scufundarea” în labirintul progresiv din Berlin Holocaust Memorial18 induce pierderea spațială ca o stare atemporală. Cei 2.700 de stâlpi din beton, stelae, sunt aranjați pe o planimetrie grid desfășurată pe 19.000 mp, speculând panta terenului; în parcursul dinamic, vizibilitatea este redusă imperceptibil, omul pierzându-se în structura repetitivă. Două artificii determină descreșterea disimulată a înălțimii pietonilor, respectiv panta imperceptibilă a terenului, corelată majorării progresive a înălțimii volumelor - o progresie stroboscopică care se joacă cu percepția scării umane. Rememorarea este stimulată de inducerea stărilor de pierdere individuală, angoasă spațială. „Știi, dacă te duci și intri în (labirint), te simți nesigur! Aceste lucruri sunt covârșitoare. Nu știu unde mă duc. Oare am să mă pierd? Sunt singur. Nu pot ține pe nimeni de mână. Și aceste lucruri, atunci când se întâmplă, te fac să simți ceea ce însemna să fii evreu în Germania anilor ’30.”19 (Peter Eisenman) Eisenman susținea traseul în scopul implicării pietonilor într-o posibilă experiență zilnică. „Vreau să fie o parte din viața ordinară, de zi cu zi. Oamenii care au mers pe lângă el spun că este foarte modest... Îmi place să cred că oamenii îl vor folosi pentru a scurta drumul, ca o experiență de zi cu zi și nu ca pe un loc sfânt.”20 Empatia generată de transpunerea simpatetică a percepției senzoriale a fost cauza primară a abstractizării, deși ulterior atacată de critici pentru gradul implicit de generalizare și lipsa simbolismului religios, determinând compromisul arhitectului și construirea unui centru de informare subteran21: „Am luptat ca să nu fie trecute numele decedaților pe pietrele comemorative, pentru că altfel s-ar fi transformat într-un cimitir.”22 O imagine conexă este aceea a memorialului din Treblinka23, de data aceasta fără o planimetrie labirintică. Precedând monumentul proiectat de Eisenman, cel de la Treblinka (1988), situl taberei de concentrare este acoperit într-o explozie metaforică de sute de pietre cu contur neregulat, aparent ruine, cu trimitere către istoria sitului dinamitat de localnici, în căutarea bijuteriilor, după cel de-al Doilea Război Mondial. Elementele punctuale la o scară mai mică decât cea amintită evocă ordinea/dezordinea, pierderea, proiectând spațialitatea arhitecturală ca un dialog între orizontală și verticală prin prisma percepției vizuale. Matricea repetabilă a construitului, labirintul gestionat ca suită a perspectivelor identice, a deschiderilor vizuale constrânse o găsim clar determinată de Daniel Libeskind în amenajarea exterioară a Grădinii Exilului24 de la Muzeul evreiesc din Berlin. 49 de coloane umplute cu pământ susțin grădina suspendată de stejari, având o spațialitate/tramă similară celei create ulterior de Eisenman, determină disimularea percepției la nivelul solului ca o recepție subterană angoasantă. Complementar abordării lui Peter Zumthor, labirintul ascunde/suspendă o grădină intangibilă, aduce în discuție o percepție a arhitecturii în termenii regăsirii, descoperirii. Drumul, în ultimă instanță, duce către adevăr și, ca atare, formele pe care arhitectura le îmbracă activează transpunerea acestuia. Determinarea ideologică derivă din vechea translație de semnificații între adevăr și frumos: splendor veri (platonicieni), splendor ordinis (Sfântul Augustin), splendor formae (Toma d’Aquino), ceea ce ne place fără concept (Kant), întruchiparea sensibilă a ideii (R. Bayer). Nu întâmplător Alexander Brodsky și Ilya Utkin25, în lucrarea grafică Forum de Mille veritatis (1987-1990), discutau imensitatea incomensurabilă, asociau spațialitatea, timpul și perceptia imediată, într-o angoasă a rătăcirii printre elemente similare - o arhitectură a substanței multiplicate, a stâlpilor într-un forum al celor 1.000 de adevăruri. Guillermo del Toro descria Labirintul faunului prin iluzia pierderii și mișcarea continuă. „Este un loc unde cotești brusc și poți avea iluzia de a te fi pierdut, dar, în fapt, ești într-un tranzit continuu spre centrul inevitabil. Aceasta este diferența. Un labirint vegetal are nenumărate fundături; labirintul poate avea iluzia unui terminus, dar întotdeauna continuă. În film îi pot atribui două sensuri concrete înțelesurilor labirintului. Unul este tranzitul fetei spre propriul centru; celălalt este parcursul ei în cadrul realității, acesta fiind real.”26 Sensibilitatea prezentă în El Laberinto del Fauno este în esență o reflexie a timpului, nu a spațiului, așa cum deducem dacă analizăm sursele de influență recunoscute27 (ne referim, în special, la Jorge Luis Borges, și percepția temporal-infinită). De referință este, în acest sens, un alt film produs de Guillermo del Toro - Cronos. Interviurile date de arhitecții P. Eisenman și D. Libeskind reflectă organizarea structurilor ca implementare a empatiei, a memoriei - fenomen temporal - implicit atrăgând noțiunea de labirint: o astfel de construcție, în metaforă sau în realitate, nu manipulează, de fapt, spațiul, ci timpul. Jocul în care te prinde un labirint este unul al memoriei, implicit motivat de interpretarea spațialității, ca o consecință a timpului. Octavian Paler discuta în Mitologii Subiective logica punctului nodal - labirint, timp, memorie. „... înainte de orice, labirintul ne vorbește, într-un fel nou, [...] despre dragoste și despre memorie. Pentru a ieși din coridoarele întortocheate, infidelul Tezeu își va aminti drumul parcurs, pentru că asta face, de fapt, Ariadna, îl ajută să nu uite în labirint... Lumea vorbește că Minotaurul nici n-a existat. Faptul că nu găseau ieșirea din labirint îi omora pe cei care erau împinși acolo”28. Într-o ultimă interpretare, labirintul se referă la structura interioară umană29. Interpretarea particulară care se desprinde este în legătură cu acest infinit al continuumului și al ciclicității. Construcția labirintică, ca sumă a elementelor, manipulează timpul investit în parcurgerea unei structuri, claustrante, este fantastică prin acest nesfârșit temporal și spațial - un cuplu care, în orice moment, poate fi definit prin celălalt element fără a-și pierde semnificația. Mișcarea ca tranziție de la o atitudine la alta30 stă în spatele percepției particular temporale. Arhitectura labirintică spelculează mișcarea stroboscopică, imaginarul senzorial în direcția pierderii spațiale, a tactilității inconfortabile (pietrele colțuroase de la Treblinka), a dinamicii agresive (Alexander Brodsky, Ilya Utkin). Compunerea și descompunerea devin mecanismele specifice spațialității inconfortabile, mizând pe repetiția elementelor constructive. „Labirintul reprezintă lumea în mod alegoric - larg/spațios pentru cei care intră în el, dar extrem de strâmt pentru cei care încearcă să se întoarcă”, afirmă inscripția din Biserica San Savino, în Piacenza, secolul al X-lea, citată și de Umberto Eco în Il Nome della Rosa. |

| Pentru sprijinul acordat în ilustrarea articolului, autoarea le mulțumește arh. Alexander Brodsky (Bureau Alexander Brodsky), arh. Vlad Eftenie, Pavilionului Serpentine Gallery. |

| 1.

Pan, în intriga filmului El Laberinto del Fauno (Labirintul Faunului), despre lumile duale.

2. El Laberinto del Fauno, regie, scenariu: Guillermo del Toro, co-producție: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, în asociere cu: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM; 2006; http://www.imdb.com /title/tt0457430/quotes, accesat: 02.03.2012; 3. Acțiunea are loc în Spania în 1944, precedând războiul civil cu cinci ani. 4. Expresia supraterană este un hibrid între recognoscibilul labirint de la Epidaur și structurile vegetale romantice. Proiecția planimetri* că subterană marchează centrul, axul ascensiunii/descensiunii, desenul incizat tip petroglifă amintind de una dintre cele mai vechi reprezentări din preistorie. De referință sunt desenele celtice, din mormântul megalitic, din insula Gavrinis, Larmor-Baden, Franța, datate cca. 3500 î.H. Reprodus și pe pardoseala Catedralei gotice din Chartre (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres, Franța, 1193-1250) desenul este unul frecvent întâlnit în Evului Mediu - un circuit tipic, cu 11 cercuri, divizat în 4 sferturi, mai precis, un maze. 5. Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (Interviu cu un Vampir), regizor: Neil Jordan, scenariu, nuvela: Anne Rice, producție: Geffen Pictures, 1994. 6. „Culturile occidentale fac diferența între realitatea interioară și cea exterioară, una având o greutate mai mare decât cealaltă. Eu nu. Am avut parte de o educație absolut nebună. Am avut o copilărie nenorocită. Și am descoperit că realitatea [interioară] este la fel de importantă ca aceea pe care o privesc chiar acum. Celălalt tranzit pe care pot să-l amintesc este acela parcurs de Spania, de la o prințesă care a uitat cine era și de unde venea la o generație care nu va cunoaște niciodată numele de fascist. Și celălalt este drumul Căpitanului căzut în propriul său labirint istoric. Acestea sunt lucruri pe care le-am pus eu. Dar apoi, așa cum am spus, labirintul este cu totul altceva. Fiecare cultură îi va atribui o greutate diferită” - Guillermo del Toro, apud Murray, Rebecca - Guillermo del Toro Talks About ”Pan‘s Labyrinth”, http://movies.about.com/ od/panslabyrinth/a/pansgt122206.htm, accesat: 02.03.2012. 7. Peter Zumthor (peisajist: Piet Oudolf) Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, Kensington Gardens, Londra, 2011. 8. Peter Zumthor, despre Serpentine Pavilion, apud Glancey, Jonathan - „Peter Zumthor unveils secret garden for Serpentine Pavilion”, The Guardian, Monday, 4 April 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/ artanddesign/2011/apr/04/ peter-zumthor-serpentine-gallery-pavilion ?INTCMP=ILCNETTXT3487, accesat: 02.02.2012. 9. Haft, Adele J. – „Maps, Mazes, and Monsters: The Iconography of the Library in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose”, Studies in Iconography 14, Arizona State University (1995), http://www.themodernword.com /eco/eco_papers_haft.html. 10. Borges, Jorge Luis - „Library of Babel”, Ficciónes- partea I, 1944-1946. 11. Deleuze, Gilles - Foucault, trans. Séan Hand. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1988, p. 96-97. 12. Alexander Brodsky & Utkin apud http://aminotes.tumblr.com/ post/426888285/ alexander-brodsky-utkin-the-intelligent-market. 13. Cf. Turner, Tom - Garden History: philosophy and design, Routledge, 2011. 14. Guillermo del Toro preferă tema labirintului planimetric, dezvoltată ca planimetrie în Hellboy și labirint grădină în El Laberinto del Fauno. Hellboy, regizor: Guillermo del Toro, scenariu: Guillermo del Toro, producție: Lawrence Gordon Productions, Starlite Films, în asociere cu Dark Horse Entertainment; 2004. 15. Semnificațiile drumului din „Labirintul” lui Del Toro, interpretate în conexiune cu un alt film al regizorului - „El espinazo del diablo”, trimit către identitatea dobândită prin maturizare. 16. Traducere liberă - El Laberinto del Fauno, regie, scenariu: Guillermo del Toro, coproducție: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, în asociere cu: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM; 2006. 17. „Intenția este aceea de a aduce cimitirul evreiesc în viața de zi cu zi a germanilor, de a-l aduce în mijlocul orașului” (traducere liberă) - Peter Eisenman, apud Marzynski, Marian - „A Jew Among the Germans” („Un evreu printre germani”), Frontline, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/ pages/frontline/shows/germans/ etc/script.html, accesat: 03.02.2012. 18. Peter Eisenman (inginer: Buro Happold), Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe - Holocaust Memorial (Memorialul evreilor uciși în Europa - Memorialul Holocaustului), Berlin, 2003-2004. 19. Peter Eisenman despre Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, 2003-2004, apud Marzynski, Marian - „A Jew Among the Germans“ („Un evreu printre germani”), Frontline, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/ frontline/shows/germans/etc/ script.html, accesat: 03.02.2012. 20. Peter Eisenman, traducere liberă, apud Rosh, Lea - „Berlin opens Holocaust memorial” („La Berlin se deschide Memorialul Holocaustului”) BBC News, 10 Mai 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/4531669.stm, accesat: 02.03.2012. 21. Un centru pentru vizitatori, în care elementele comemorative să facă legătura directă cu pierderile poporului evreu, suferite în timpul Holocaustului. „Va fi un memento pentru țara agresorilor” - jurnalista Rosh, Lea, op.cit. 22. Peter Eisenman, apud Rosh, Lea, op.cit. 23. Haupt & Dyszenko, Memorialul „Valley of Stones”, Treblinka, Radzilow, 1988. 24. Studio Daniel Libeskind, Garden of Exile and Emigration (Grădina Exilului și Emigrării), Jewish Museum Berlin, Germania, 1999 - amintind de evreii care au fost nevoiți să părăsească Berlinul, cf.*** Studio Daniel Libeskind - Proiect Brief, http://daniel-libeskind.com/ projects/jewish-museum-berlin, accesat: 08.11.2011. 25. Lucrările grafice ale arhitecților ruși: Alexander Brodsky, Ilya Utkin. Lois Nesbitt (ed.) - Brodsky & Utkin: The Complete Works, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2003. 26. „Culturile occidentale fac diferența între realitatea interioară și cea exterioară, una având o greutate mai mare decât cealaltă. Eu nu. Am avut parte de o educație absolut nebună. Am avut o copilărie nenorocită. Și am descoperit că realitatea [interioară] este la fel de importantă ca aceea pe care o privesc chiar acum. Celălalt tranzit pe care pot să-l amintesc este cel parcurs de Spania, de la o prințesă care a uitat cine era și de unde venea, la o generație care nu va cunoaște niciodată numele de fascist. Și celălalt este drumul Căpitanului căzut în propriul său labirint istoric. Acestea sunt lucruri pe care le-am pus eu. Dar apoi, așa cum am spus, labirintul este cu totul altceva. Fiecare cultură îi va atribui o greutate diferită” - Guillermo del Toro, apud Murray, Rebecca - Guillermo del Toro Talks About ”Pan‘s Labyrinth”, http://movies.about.com/od/ panslabyrinth/a/pansgt122206.htm, accesat: 02.03.2012. 27. „Printre lucrările care i-au servit drept sursă de inspirație se numără cele ale lui: Lewis Carroll seria «Alice», Jorge Luis Borges «Ficciones», Arthur Machen «The Great God Pan and The White People», Lord Dunsany «The Blessing of Pan», Algernon Blackwood «Pan‘s Garden» și lucrările lui Francisco Goya. În 2004, del Toro a declarat: «Pan este o poveste originală. Unii dintre scriitorii mei preferați (Borges, Blackwood, Machen, Dunsany) au explorat figura zeului Pan și simbolul labirintului. Găsesc aceste lucrurile foarte convingătoare și încerc să le amestec și să mă joc cu ele»! - „Influences”, Pan’s Labyrinth, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki /Pan%27s_Labyrinth#Influences, accesat: 03.02.2012. 28. Paler, Octavian - Mitologii Subiective, Editura Eminescu, ediția a II-a, București, 1976, p. 31. 29. A evada din labirint este o problemă de timp, nu de spațiu, fiindcă spațiul are relevanță doar în raport cu ceilalți, nu cu sinele. 30. Auguste Rodin apud Arnheim, Rudolf - Arta și percepția vizuală: o psihologie a văzului creator. Ediția a II-a, traducere de Florin Ionescu, Polirom, București, 2011, p.417. |

| Bibliografie

Arnheim, Rudolf - Arta și percepția vizuală: o psihologie a văzului creator. Ediția a II-a, traducere de Florin Ionescu, Polirom, București, 2011. Arnheim, Rudolf - Forța centrului vizual. București: Editura Meridiane, 1995. Barker, Jennifer M. - The Tactile Eye: touch and the cinematic experience. London: University of Califonia Press, Ltd., 2009. Borges, Jorge Luis - „Library of Babel”, Ficciónes, p. I, 1944-1946. Deleuze, Gilles – „The Fold-Leibniz and the Baroque: The Pleats of Matter”. Architectural Design Profile, No.102: Folding in Architecture, 1993. Deleuze, Gilles - Difference and Repetition. Tr.: Paul Patton, Columbia University Press, New York, 1994. Crișan, Ana-Maria - Anagrama arhitecturii imaginare. Metamorphosis - reevaluarea paradigmei temporale în arhitectură, teză de doctorat, 2012. Eco, Umberto - Arta și Frumosul în Estetica Medievală. București: Editura Meridiane, 1999. Eco, Umberto - Numele trandafirului. Hyperion, București, 1992. Eco, Umberto - Șase plimbări prin pădurea narativă. Constanța: Pontica, 1997. Eco, Umberto - Limitele Interpretării. Constanța: Pontica, 1996. Gombrich, E.H. - The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art (The Wrightsman Lectures, V. 9), Phaidon Press; 2nd edition, 1994. Hocke, Gustav Rene - Lumea ca labirint. Traducere de Victor H. Adrian. București: Editura Meridiane, 1973. Kern, Hermann - Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings over 5000 Years. Prestel, Verlag Munich, 2000. Paler, Octavian - Mitologii Subiective, Editura Eminescu, ediția a II-a, București, 1976. Turner, Tom - Garden History: philosophy and design, Routledge, 2011. Zumthor, Peter - Atmospheres: Architectural Environments - Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser Architecture, 5th Printing. Edition, 2006. Lucrări de referință: Haupt & Dyszenko, Memorialul „Valley of Stones”, Treblinka, Radzilow, 1988. Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, 2003-2004. Studio Daniel Libeskind, Garden of Exile and Emigration, Jewish Museum, Berlin, Germania, 1999. Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, Forum de Mille Veritatis, 1987/90, 30 3/8“ x 22 1/2“, gravură („The Intelligent Market”, Central Glass Co. Competition Japan Architect, Tokyo, Japan, 1987). Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, The Intelligent Market (Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition 1987), gravură. Peter Zumthor (peisajist: Piet Oudolf) Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, Kensington Gardens, Londra, 2011. El Laberinto del Fauno (Labirintul Faunului), regie, scenariu: Guillermo del Toro, coproducție: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, în asociere cu: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM; 2006; Hellboy, regizor: Guillermo del Toro, scenariu: Guillermo del Toro, producție: Lawrence Gordon Productions, Starlite Films, în asociere cu Dark Horse Entertainment; 2004. Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles (Interviu cu un Vampir), regizor: Neil Jordan, scenariu, nuvela: Anne Rice, producție: Geffen Pictures, 1994. |

| „A long time ago, on the underground realm where there are no lies or pain, lived a princess who dreamed of the human world. She dreamed of blue skies, breezes and bright sun. One day, deceiving her jailers, the Princess escaped. Once she was out, the brilliance blinded her and deleted any recollection of her memory. She forgot who she was and where she was. She suffered from cold, disease and pain. Finally, she died. However, her father, the King, always knew that the Princess’s soul would return, perhaps in another body, in another place or at another time. And ke kept on waiting until he pulled the last breath, until the world ceased to spin.”[1] – (Guillermo del Toro/ Pan, El Laberinto del Fauno)

The introduction of the cinematographic work El Laberinto del Fauno[2] anticipates the way of the little girl Ofelia, lost from reality. The key space introduced by the director and writer Guillermo del Toro is Pan’s labyrinth, representing the point of confluence between Franco’s Spain reality in a magical originating world. Paradoxically, the anxieties of the historical period (prior to World War II[3]) determine a fracture of the story developed on two levels – on one hand the reality of the guerrillas fighting, on the other a fantastic world imagined by the children. The two levels meet at the nodal point of the labyrinth – it offers the access to a different temporal unit, a place of initiation, discoveries, shift and return in a pure world, a world of fairy tales and of the lost time "without lies, without pain". The ability to introduce the entity of the labyrinth on a frequency that meets the architectural perceptions of the element is outstanding. Guillermo del Toro composes a concentric recurring system, by coupling two of the typical, referential forms of the labyrinth[4] - he creates a world built hierarchically in successive layers. At the ground level, the spatial plot develops in the garden space, reminiscent of the Romantic vegetal routes, while the underground recalls for the originating typology of the labyrinth / maze, following a planimetric circuit. Frequently, the fairy tales include the typology of the garden by developing the model of the charmed, sacred forests, where temples or traces of a crumbling architecture, consumed by vegetation, are to be seen. Often associated with the landscape facilities in the 15-19 centuries, the labyrinth and the fountain are parts of the same metaphorical system in the cinematographic fantasies. Staking on the complexity of the constructive system - stairs, walls, poles – the labyrinth exploits the horizontal spaciousness, operating both at ground level in El Laberinto del Fauno and underground in Interview with a Vampire[5]. The typology of the fountain develops the vertical descending – ascending spindle; it speculates the purity of the form dug ad invertum and the force of the centre, becoming a symbolic depiction of the underground architecture as an access point in another world. „The labyrinth is a very, very powerful sign,” - “It’s a primordial, almost iconic symbol. It can mean so many things, culturally, depending on where you do it. But the main thing for me is that, unlike a maze, a labyrinth is actually a constant transit of finding, not getting lost. It’s about finding, not losing, your way. That was very important for me.”[6] Peter Zumthor materializes the labyrinth in terms of sequence and of an introvert structure. The metaphor of the restoration is the basis for the Serpentine Gallery Pavilion[7] project; under the crown of the trees in Kensington Gardens in London, the Hidden Garden (Hortus conclusus) is apparently a parallelepiped, opaque, a much too short volume, metaphorically concentrating the light and the vegetation in the central atrium. In a chromatic interpretation, the Centre is positive, bright, dominant, antithetic to the building itself - a land-based enclosure, drawn by the constant gravitation, burdened by dark colours and minimal openings. "The concept is the hortus conclusus, a contemplative room, a garden within a garden. The building acts as a stage, a backdrop for the interior garden of flowers and light. Through blackness and shadow one enters the building from the lawn and begins the transition into the central garden, a place abstracted from the world of noise and traffic and the smells of London – an interior space within which to sit, to walk, to observe the flowers. This experience will be intense and memorable, as will the materials themselves – full of memory and time."[8] The building is a garden in the garden, a world in another world in the same manner in which Umberto Eco designed his labyrinth[9]. In the spirit of post-modernist theories (Il Nome Della Rosa), Eco supports the cycle of the fairy tales and their reporting to other stories, in whole or in part: "books always talk about other books and each story tells another story that has already been told." He applies the same recurrence to the architectural constructions. Similarly, for Jorge Luis Borges, the universe in Library of Babel is described as a library, harbouring endless symmetrical rooms, containing the same number of books, containing the same number of symbols.[10] Anticipating the contemporary games, the visionary architects, Alexander Brodsky & Ilya Utkin, reinterpreted and transposed the concentric geometry of the labyrinth by multiplying enclosures. In their graphic work, The Intelligent Market, they compose a seemingly growing by auto-generating cellular structure - engraving, Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition, 1987. In a complementary perspective, the theorist Gilles Deleuze highlights the interpretation of the successive plans: "the outside is not a fixed limit, but a moving subject animated by the peristaltic movements, folds and plies that together make up an interior: there are none other than the exterior, even the inside of the outside." [11] In a gesture of material compression, Peter Zumthor condensed the Kensington Gardens pavilion in the outer wall thickness; he minimizes the width of the built structure and amplifies the proportion of the garden-centre. Analog to Umberto Eco's structures, the solution calls for the labyrinthine typology, such as: sectioned perspectives, a fragmented admission of the light, obscure chromatisms, a cyclic-concentric route, offering similar frustrating perspectives. The road / route is identified as a primary spatial factor, as the constructive elements subordinate thereto. Within the context, the walls become borders, being primarily straightforward plans. „We begin our way with firm decision to learn and to understand everything. The endless corridors with endless niches, each of which we must observe. Next turn gives us a new perspective with new niches. And at the end of the way - the last glance at all what we have gone throwgh.”[12] ( Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin ) Returning to the labyrinth in El Laberinto del Faun, we note the relevance of the road in terms of purposefulness. The garden is designed based on the labyrinth interpreted as a ritual and sacrificial space; according to its religious / astrological components[13], it focuses on the transition between the Earth and the underground world. Ofelia follows the labyrinth, volumetrically built, finds the central shaft / fountain, descends and, in the last stage of discovery, faces a planimetric "maze"[14] incised in stone. The director speculates the significance of the descent by associating the typologies of the types underground architectures with the columbarium model and the significance of the necropolis; he reunites them stylistically. The spiritual fulfilment, the process of growing up[15], the self awareness as a result of the trials, is the key road from El Laberinto del Fauno; the abandon of the road and the impossibility to finish the maze involve loss of sensitivity, of the innocence of childhood. "Your spirit will remain forever among people. You will grow old too, you will die too. And all the memories about you will fade in time. And we will elapse with them.” (Pan discussing with Ofelia, El Laberinto del Fauno)[16] The monuments dedicated to Holocaust designed by Peter Eisenman and Daniel Libeskind in Berlin: the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, 2003-2004 and the Garden of Exile and Emigration, Jewish Museum, 1999, talk about loss, time and spirit, in terms of the spatial labyrinth. In the contemporary interpretation, the updating of the labyrinthine garden designs into monumental architectural spaces is done either through uniformity, as a matrix- labyrinthine structure (Daniel Libeskind), as a stroboscopic multiplication of the parallelepiped volumes - a grave stones’ carpet[17] in Eisenman’s memorial, or as a field covered by rocky fragments at Treblinka (Haupt & Dyszenko). The "sinking" into the progressive labyrinth of the Berlin Holocaust Memorial[18] induces the spatial loss as a timeless estate. The 2,700 concrete pillars, stelae, are placed on a grid planimetry deployed on 19,000 sq m, speculating the land slope; along the dynamic roadmap, the visibility is reduced imperceptibly, one losing himself in a repetitive structure. Two artifices induce a concealed decreasing of the pedestrians’ height, namely the imperceptible slope of the land correlated with a progressive increase of the height of the volumes - a stroboscopic progression that is playing with the perception of human scale. The recall is stimulated by inducing the states of individual loss, of spatial anguish. " You go and walk in it, and you will feel uncertain, you know? These things are tilting. I don't know where I'm going. Am I going to get lost? I'm alone. I can't hold anybody's hand. And that, when they get done, was what it felt like to be a Jew in Germany in the '30s. That all. Basta. That's the monument."[19] ( Peter Eisenman ) Eisenman supported the idea that, by following the undulating pathway, the pedestrians may be involved in a daily experience. "I want it to be a part of the everyday life. People that went on around it, say it is very humble... I like to think that people will use it for short cuts, as an everyday experience, not as a holy place."[20] The empathy generated by the transposition of the sympathetic sensory perception was the primary cause of abstraction. Nevertheless, the abstraction was later attacked by critics for the implied degree of generalization and the lack of religious symbolism, hence the architect’s compromise and his agreement for building an underground information centre[21]: "I fought to keep names off the stones, because having names on them would turn it into a graveyard."[22] A related image is that of the Valley of Stones Memorial[23], this time without a labyrinthine planimetry. Treblinka Memorial (1988) precedes the monument designed by Eisenman; the concentration camp site is covered in a metaphorical explosion by hundreds of stones with irregular edges, apparently ruins, with reference to the history of the site blown up by the locals that were looking for jewellery, after World War II. Specific items, at a smaller scale than the previously mentioned ones, evoke the order / disorder, the loss, by projecting the architectural spaciousness as a dialogue between horizontal and vertical plans, visually perceived. In his construction of the Garden of Exile[24] in Jewish Museum in Berlin, Daniel Libeskind clearly determines the repeatable matrix of the built area: the labyrinth is managed as a sequence of identical perspectives, of partially closed visual openings. clear of in the. 49 columns, filled with ground, support the suspended oak garden, with a widening area similar to the one further created by Eisenman, concealing the perception at ground level as an underground full of anguish reception. Complementary to Peter Zumthor’s approach, the labyrinth hides / suspends an intangible garden and brings into question a perception of the architecture in terms of retrieval and discovery. The road ultimately leads to the truth, and as such, the architectural forms activate its implementation. The ideological determination derives from the old translations of the meanings between truth and beauty: splendor veri (Plato’s doctrine), splendor ordinis (Saint Augustine), splendor formae (Toma d’Aquino), what we like without concept (Kant), the sensitive embodiment of the idea (R. Bayer). Not incidentally, Ilya Utkin and Alexander Brodsky[25], in the graphics Forum de Mille Veritatis (1987-1990), were discussing the immensity of the immeasurable, they associated spaciousness, time and immediate perception in an anguish of drifting among similar items - hence a substance multiplied by architecture, the pillars in a forum of the 1000 truths. Guillermo del Toro described Pan's labyrinth through the illusion of the loss and the continuous movement: „It is a place where you do sharp turns and you can have the illusion of being lost, but you are always doing a constant transit to an inevitable center. That’s the difference. A maze is full of dead ends, and a labyrinth may have the illusion of having a dead end, but it always continues. I can ascribe two concrete meanings of the labyrinth in the movie. One is the transit of the girl towards her own center, and towards her own, inside reality, which is real. ”[26] The sensitivity present in El Laberinto del Fauno is essentially a reflection of the time, not of the space, as we abstract from the works of influence[27] (we refer in particular to Jorge Luis Borges, and the infinite temporal perception). Reference in this regard is another film produced by Guillermo del Toro - Cronos. The interviews given by P. Eisenman and D. Libeskind reflect the organization of built structures as an implementation of the empathy, of the memory – a time-default phenomenon – hence the notion of the labyrinth: such a construction, in metaphor or reality, not actually handles space, but rather time. The labyrinth catches oneself in a special game of the memory, motivated by the interpretation of spaciousness in terms of time. In Mitologii Subiective (Subjective Mithologies) Octavian Paler discussed the logics of the focal point – labyrinth, time, memory: „...first of all, the labyrinth talks, in a new way, [...] about love and about the memory. To exit the twisting corridors, the unfaithful Theseus will remember the followed road, that is what Ariadna does in fact, she helps him to remember the maze ... The world speaks that the Minotaur did not exist. The fact they could not find out the exit killed those that were pushed down there”[28]. In a final interpretation, the labyrinth refers to the inner human structure [29]. A particular emerging interpretation is connected to this infinity of the continuum and of the cycles. The labyrinthine construction, as the sum of the elements, manipulates the time invested in travelling through a given claustrophobic structure; it is a fantastic construction in this endless time and space – a couple, which at any moment may be defined by the other element without losing its meaning. The adjustability , as a transition from one attitude to another[30], stands behind the particular temporal perception. The labyrinthine architecture speculates the stroboscopic mobility, the sensorial imaginary in terms of spatial loss, the uncomfortable tactility (the sharp edged stones in Treblinka), the aggressive dynamics (Alexander Brodsky, Ilya Utkin). Composition and decomposition become the specific mechanisms for the uncomfortable spaciousness, staking on the repetition of the construction elements. „Hunc mundum Laberinthus denotat iste: Intrati largus, redeunti set nimis artus ..." - „The labyrinth is the allegory of the world – largely wide for those who enter it, but extremely tight for those who try to come back" says the inscription in the Church of San Savino, in Piacenza (the 10th century), quoted by Umberto Eco in Il Nome della Rosa as well. |

| Special thanks for the support in illustrating this article goes to: architect Alexander Brodsky (Bureau Alexander Brodsky), architect Vlad Eftenie, Peter Zumthor (courtesy of Serpentine Gallery Pavilion).

llustratrations: Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion,2011, Photograph © Walter Herfst, courtesy of Serpentine Gallery Pavilion. Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, 2011, Photograph © John Offenbach, courtesy of Serpentine Gallery Pavilion Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, The Intelligent Market, (Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition 1987), courtesy of Bureau Alexander Brodsky. Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, Forum de Mille Veritatis, 1987/90, 30 3/8" x 22 1/2", engraving ("The Intelligent Market," Central Glass Co. Competition Japan Architect, Tokyo, Japan, 1987), courtesy of Bureau Alexander Brodsky. Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, 2003-2004. ©photo: Vlad Eftenie |

|

[1] Pan speaking about the dual worlds in El Laberinto del Fauno. [2] El Laberinto del Fauno (Pan's Labyrinth), director and script: Guillermo del Toro, co-production: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, in association with Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM, 2006. http://www.imdb.com/title /tt0457430/quotes, accessed: 02.03.2012. [3] The action takes place in the Fascist Spain in 1944, succeeding the Civil War with five years (1936-1939). [4] The over ground expression is a hybrid between the recognizable maze at Epidaurus and the Romantic vegetal structures. The underground planimetric projection marks the centre, the descending - ascending spindle, while the incised drawing, similar to petroglyphs, recalls one of the earliest depictions of prehistoric times. For reference are the Celtic drawings from the megalithic tomb on the island of Gavrinis, Larmor-Baden, France, dated c. 3500 B.C. Reproduced on the floor of the Gothic Cathedral of Chartres (Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres, France, 1193 – 1250), the drawing is one frequently encountered in the middle ages - a typical circuit with 11 circles, divided into 4 quarters, more precisely a maze. [5] Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles, director: Neil Jordan, script & novel: Anne Rice, production: Geffen Pictures, 1994. [6] „I think that Western cultures make a difference about inner and outer reality, with one having more weight than the other. I don’t. I come from an absolutely crazy upbringing. I had a f**ked up childhood. And I have found that [the inner] reality is as important as the one that I’m looking at right now. The other transit I can say is the transit that Spain goes through, from a princess that forgot who she was and where see came from, to a generation that will never know the name of the fascist. And, the other one is the Captain being dropped in his own historical labyrinth. Those are things I put in. But then, as I said, the labyrinth is something else. Each culture will ascribe a different weight to it.” - Guillermo del Toro, apud Murray, Rebecca - Guillermo del Toro Talks About "Pan's Labyrinth", http://movies.about.com/od /panslabyrinth/a/pansgt122206.htm, accessed: 02.03.2012. [7] Peter Zumthor, (landscape architect: Piet Oudolf) Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, Kensington Gardens, London, 2011. [8] Peter Zumthor, about Serpentine Pavilion, apud Glancey, Jonathan – „Peter Zumthor unveils secret garden for Serpentine pavilion”, The Guardian, Monday 4 April 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/ 2011/apr/04/peter-zumthor-serpentine-gallery-pavilion?INTCMP=ILCNETTXT3487, accessed: 02.02.2012. [9] Haft, Adele J. – "Maps, Mazes, and Monsters: The Iconography of the Library in Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose", Studies in Iconography 14, Arizona State University, (1995), http://www.themodernword.com/ eco/eco_papers_haft.html. [10] Borges, Jorge Luis -"Library of Babel”, Ficciónes- part I, 1944-1946. [11] Deleuze, Gilles - Foucault, trans. Séan Hand. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1988, p.96-97. [12] Alexander Brodsky & Utkin apud http://aminotes.tumblr.com/post/ 426888285/alexander-brodsky-utkin-the-intelligent-market [13] Cf. Turner, Tom - Garden History: Philosophy and Design, Routledge, 2011. [14] Guillermo del Toro prefers the theme of the planimetric labyrinth, developed as planimetry in Hell Boy, and a garden maze in El Laberinto del Fauno. Hellboy, director: Guillermo del Toro, script: Guillermo del Toro, production: Lawrence Gordon Productions, Starlite Films, in association with Dark Horse Entertainment, 2004. [15] The significances of the road in del Toro's El Laberinto del Fauno, interpreted in conjunction with his other film - El espinazo del diablo - send to the identity gained through growing up. [16] (free translation) El Laberinto del Fauno, director, script: Guillermo del Toro, co-production: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, in association with: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM: 2006. [17] “... And it's to bring the Jewish cemetery into the everyday experience of the German, in the middle of the city.” - Peter Eisenman, apud Marzynski, Marian - "A Jew Among the Germans" - Frontline, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/ frontline/shows/germans/etc/script.html, accessed: 03.02.2012. [18] Peter Eisenman, (engineer: Buro Happold), Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe - Holocaust Memorial, Berlin, 2003-2004. [19] Peter Eisenman about Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, 2003-2004, apud Marzynski, Marian - "A Jew Among the Germans"), Frontline, http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/ frontline/shows/germans/etc/script.html, accesed: 03.02.2012. [20]Peter Eisenman, apud Rosh, Lea - "Berlin opens Holocaust memorial" BBC news, May 10th, 2005, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/4531669.stm, accessed: 02.03.2012. [21] A visitors’centre, where commemorative items link directly with the Jewish people and their suffered losses during the Holocaust. “It will be a memento for the aggressors’ country.”- Journalist Rosh, Lea, quoted works. [22] Peter Eisenman, apud Rosh, Lea, quoted works. [23] Haupt & Dyszenko, „Valley of Stones” Memorial, Treblinka, Radzilow, 1988; [24] Studio Daniel Libeskind, Garden of Exile and Emigration Jewish Museum Berlin, Berlin, Germania, 1999 – in Memoriam of the Jews forced out of Berlin, cf.*** Studio Daniel Libeskind – Proiect Brief, http://daniel-libeskind.com/ projects/jewish-museum-berlin, accessed: 08.11.2011. [25] The graphic works of the Russian architects: Alexander Brodsky, Ilya Utkin. Lois Nesbitt (ed) - Brodsky & Utkin: The Complete Works, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2003. [26] „I think that Western cultures make a difference about inner and outer reality, with one having more weight than the other. I don’t. I come from an absolutely crazy upbringing. I had a f**ked up childhood. And I have found that [the inner] reality is as important as the one that I’m looking at right now. The other transit I can say is the transit that Spain goes through, from a princess that forgot who she was and where see came from, to a generation that will never know the name of the fascist. And, the other one is the Captain being dropped in his own historical labyrinth. Those are things I put in. But then, as I said, the labyrinth is something else. Each culture will ascribe a different weight to it.”- Guillermo del Toro, apud Murray, Rebecca - Guillermo del Toro Talks About "Pan's Labyrinth", http://movies.about.com/od/ panslabyrinth/a/pansgt122206.htm, accessed: 02.03.2012. [27] „Some of the other works he drew on for inspiration include: Lewis Carroll „Alice” books, Jorge Luis Borges „Ficciones”, Arthur Machen „The Great God Pan and The White People”, Lord Dunsany „The Blessing of Pan”, Algernon Blackwood „Pan's Garden” and Francisco Goya’s works. In 2004, del Toro said: << Pan is an original story. Some of my favourite writers (Borges, Blackwood, Machen, Dunsany) have explored the figure of the god Pan and the symbol of the labyrinth. These are things that I find very compelling and I am trying to mix them and play with them. >> ” - „Influences”, Pan's Labyrinth, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Pan%27s_Labyrinth#Influences, accessed: 03.02.2012. [28] Paler, Octavian - Mitologii Subiective, Ed. Eminescu, second edition, Bucharest, 1976 p. 31. [29] To elope from the labyrinth is a matter of time and not of space, as the space is relevant only reported to others and not to oneself. [30] Auguste Rodin apud Arnheim, Rudolf - Arta si perceptia vizuala: o psihologie a vazului creator. second edition, Polirom, Bucharest, 2011, p.417. |

| [1] Pan speaking about the dual worlds in El Laberinto del Fauno. |

BibliographyArnheim, Rudolf – Arta si perceptia vizuala: o psihologie a vazului creator. ediția a II-a, traducere de Florin Ionescu, Polirom, București, 2011 Arnheim, Rudolf – Forța centrului vizual. Bucuresti: Editura Meridiane, 1995. Barker, Jennifer M. – The Tactile Eye: touch and the cinematic experience. London: University of Califonia Press, Ltd., 2009. Borges, Jorge Luis -"Library of Babel”, Ficciónes, p. I, 1944-1946. Deleuze, Gilles – “The Fold-Leibniz and the Baroque: The Pleats of Matter.” Architectural Design Profile No.102: Folding in Architecture, 1993 Deleuze, Gilles – Difference and Repetition. tr: Paul Patton, Columbia University Press, New York, 1994. Crișan, Ana-Maria - Anagrama arhitecturii imaginare. Metamorphosis - reevaluarea paradigmei temporale în arhitectură, Ph.D. Thesis, 2012. Eco, Umberto – Arta si Frumosul in Estetica Medievala. Bucuresti: Editura Meridiane, 1999. Eco, Umberto – Numele trandafirului. Hyperion, Bucuresti, 1992. Eco, Umberto – Șase plimbari prin padurea narativa. Constanta: Pontica, 1997. Eco, Umberto – Limitele Interpretarii. Constanta: Pontica, 1996. Gombrich, E.H. – The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art (The Wrightsman Lectures, V. 9), Phaidon Press; 2 edition, 1994. Hocke, Gustav Rene – Lumea ca labirint. Traducere de Victor H. Adrian. Bucuresti: Editura Meridiane, 1973. Kern, Hermann – Through the Labyrinth: Designs and Meanings over 5000 Years. Prestel, Verlag Munich, 2000 Paler, Octavian – Mitologii Subiective, Ed. Eminescu, ed. a II-a, București, 1976. Turner, Tom – Garden History: philosophy and design, Routledge, 2011. Zumthor, Peter – Atmospheres: Architectural Environments – Surrounding Objects. Basel: Birkhäuser Architecture, 5th Printing. Edition, 2006. Reference Works: Haupt & Dyszenko, „Valley of Stones” Memorial, Treblinka, Radzilow, 1988. Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, 2003-2004. Studio Daniel Libeskind, Garden of Exile and Emigration, Jewish Museum, Berlin, Germania, 1999. Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, Forum de Mille Veritatis, 1987/90, 30 3/8" x 22 1/2", engraving ("The Intelligent Market," Central Glass Co. Competition Japan Architect, Tokyo, Japan, 1987). Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, The Intelligent Market, (Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition 1987), gravură. Peter Zumthor, (peisajist: Piet Oudolf) Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, Kensington Gardens, Londra, 2011. El Laberinto del Fauno, director, script: Guillermo del Toro, co-production: Estudios Picasso, Tequila Gang, Esperanto Filmoj, in association with: Sententia Entertainment, Telecinco, OMM; 2006; Hellboy, director: Guillermo del Toro, script: Guillermo del Toro, production: Lawrence Gordon Productions, Starlite Films, in association with Dark Horse Entertainment; 2004. Interview with the Vampire: The Vampire Chronicles, director: Neil Jordan, script / novel: Anne Rice, production: Geffen Pictures, 1994. |

1 Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion,

Kensington Gardens, Londra, 2011

© Walter HERFST prin amabilitatea Serpentine Pavilion

2 Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion,

Kensington Gardens, Londra, 2011

© Walter HERFST prin amabilitatea Serpentine Pavilion

3 Peter Zumthor, Serpentine Gallery Pavilion,

Kensington Gardens, Londra, 2011

© John OFFENBACH prin amabilitatea Serpentine Pavilion

4 Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, Forum de Mille Veritatis -

Forum of Thousand Truths,

Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition Tokio, Japonia, 1987/90

© Brodsky & Utin prin amabilitatea Bureau Alexander Brodsky

5 Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,

Berlin, 2003-2004

©Fotografii: Vlad Eftenie

6 Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,

Berlin, 2003-2004

©Fotografii: Vlad Eftenie

7 Peter Eisenman, Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe,

Berlin, 2003-2004

©Fotografii: Vlad Eftenie

8 Alexander Brodsky & Ilia Utkin, The Intelligent Market,

Central Glass International Architectural Design Competition

1987, Tokio, Japonia,

© prin amabilitatea BureauAlexander Brodsky.