J.R.R. Tolkien versus Italo Calvino

|

Autoarea multumește artistei Beatrice Coron pentru sprijinul acordat în ilustrarea articolului. LUCRĂRI: BEATRICE CORON FOTOGRAFII: ETIENNE FROSSARD

|

| IPOSTAZE ARHITECTURALE IMAGINARE |

| „Mintea omenească este în stare să creeze imaginea unor lucruri care nu există în realitate sau care nu sunt prezente. Numim «fantezie» capacitatea de a genera imagini și noțiuni. Dar în zilele noastre, termenul de «fantezie» a început să fie folosit (și nu în limbajul curent, ci chiar în jargonul profesional) în legătură cu ceva mult mai elevat decât creația propriu-zisă (aplicată la ceea ce era socotită drept un produs al imaginației) și a devenit o formulare mai concisă a ceea ce altă dată numeam «putere de creație». Este vorba despre o încercare ce, trebuie să vă mărturisesc, dorește să limiteze și totodată să deformeze noțiunea de «imaginație creatoare», dându-i înțelesul de «capacitatea de a împrumuta unor creații imaginare o serie de caracteristici reale ascunse» (notă: adică, tocmai ceea ce dirijează sau induce Credința Secundară)” - J.R.R. Tolkien… despre poveștile cu zâne, „FANTEZIA”, „On Fairy Stories”.(„Despre poveștile cu zâne”). Presented to Charles Williams, Clive Staples Lewis (ed.). Oxford University Press, London, 1947. |

| CONSTRUCȚIA ICONICĂ ÎNTRE DIMENSIUNEA ISTORICĂ ȘI CEA FANTASTICĂ

„WHAT THE PAST AND THE FUTURE HAVE IN COMMON IS OUR IMAGINATION, WHICH CONJURES THEM...”1 (JUHANNI PALLASMAA) Lumile imaginate (imaginare) edifică arhitectura ca imagine a timpului între realitatea unicei identități a omului modern și identitățile multiple ale celui postmodern. Cadrul construit al poveștilor este scenografia care contextualizează, induce dimensiunea fantastică, palierul vizual care articulează „întâlnirea lumii și a minții omenești”. El se adresează privitorului prin suma elementelor familiare, recognoscibile, prin ceea ce numim tradiție ca sumă a trasăturilor specifice. Urmărind procesul imaginar arhitectural ne întrebăm: ce transmite edificatul imaginat? Care este raportul tradiție-identitate? CONSTRUCȚIA ICONICĂ ȘI DIMENSIUNEA ISTORICĂ2 În context narativ, dimensiunea fantastică a trilogiei Stăpânul Inelelor (The Lord of The Rings), de J. R. R. Tolkien3, se bazează pe proiecția „poveștii” ca o întâmplare într-un alt timp istoric. Asimilarea stilurilor arhitecturale popoarelor, grupurilor, este o proiecție formală, tipică reprezentării cinematografice din LOTR4, care susține caracterul scenografic în sensul de încadrare și determinare. Regizorul Peter Jackson folosește iconicul în elaborarea cadrului arhitectural spre a amplifica conflictul epic caracteristic ficțiunii lui Tolkien, cu preferință clară către determinarea stilistic europeană. Cele patru stiluri care transpar din versiunea cinematografică dezvoltă arhitecturi vernaculare, naturaliste, grotești și, respectiv, arheologice5, așa cum remarcau și Ernest Mathijs și Murray Pomerance în From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. „Romanul lui Tolkien tinde să construiască într-o manieră mult mai apropiată de basm noțiunea de magic decât mulți dintre urmașii săi de gen. […] prin interesul pentru istorie, politică, război și eroul-rege, «Stăpânul Inelelor» datorează mai multe epicului și romanticului decât basmului.”6 Forma atașată funcțiunii, din punct de vedere al modelului istoric, străbate întreaga trilogie cinematografică. Ceea ce rămâne neschimbat este, în mod corect, praxiologic, materialul de construcție care dă o identitate definibilă geografic și, în consecință, funcțională. Universul pașnic din Shire este descris prin vocabularul vernacularului britanic. Confortul și domesticul transpar din stilul habitatului pastoral la o scară mică: poduri, mori de apă, case dezvoltate pe parter sau integrate în relieful dealurilor. Interioarele casei lui Bilbo sunt consecvente aceleiași linii ale vernacularului - interioare minimale, spații ample orizontale, goluri circulare. Lumina filtrată a interioarelor, texturile blânde ale lemnului și pământului, toate concurează, cu un puternic accent teluric, în determinarea atmosferică. Complementar, universul elfilor din Rivendell și Lothlorien, situat în pădure, mizează pe reinterpretarea stilistică a Art Nouveau-ului, de la sfârșitului de secol al XIX-lea, în forma sa cosmopolită cu influențe gotice. Departe de a fi un mimetism autentic, vocabularul contează pe structura-grafică a stilului, dezvoltând ideea biomorfismului - casele fiind suspendate pe trunchiurile copacilor. Filigranarea structurilor, limbajul fluid al liniilor, ramurile sinuoase cu care sunt îmbrăcate construcțiile concurează înspre camuflarea romantică și dematerializarea specifică naturalismului psihedelic și Art Nouveau-ului. Antitetic, răul devine goticul grotesc cu spațiile subterane, unghiurile ascuțite și răceala interioarelor în multiplele exemple: Isengard, Mordor, Barad Dûr, Minas, Morgul, Poarta Neagră, intrarea din Mount Doom. Monumentalul este reinterpretat în sensul greoi și opresiv, amplificat cromatic. În Midle Earth, limita dintre natural și fabricat se dizolvă într-un gest tectonic apăsător. Metalul este materialul pe care se construiește o întreagă estetică torționară, amintind de seriile lui G. B. Piranesi și de protomecanica goticului târziu. Mecanismele metalice transpun cinematografic reacția secolului al XIX-lea vizavi de revoluția materialului, respectiv repulsia lui Tolkien față de materialul rece al revoluției industriale, similară recepției negative a Turnului Eiffel în 1889. Orașele eroice se identifică cu elansarea volumetrică, cromatica albă a pietrei, asumându-și vestigiile stilului arheologic. Cadrele arhitecturale se disting clar în două categorii - de piatră și de lemn (nordice), cu trimiteri către monumentele medievale. Cel mai nordic, Rohanul regelui Theoden, face parte din a doua categorie, cu influențe scandinave tradiționale (fortăreața vikingă de secol al X-lea din Trelleborg) și anglo-saxone7. Minas Tirith și Helm’s Deep evocă influențe bizantine, vikinge, romanice și gotice timpurii. Asistăm la o dublă interpretare a modelui concentric al Babelului, pozitiv elansat, alb, cu o geometrie planimetrică ordonată radial și, respectiv, negativ, gotic, agresiv, cu o structură nefinalizată, în construcție, aparent haotică. Amplificarea monumentalului urmează schema tipică a scenelor filmice ample, în care cetățile sunt amplasate izolat. Cea mai spectaculoasă construcție, Minas Tirith este dezvoltată pe baza descrierii originare, „echivalent al Romei sau al Bizanțului Antic”8, cu o clară corespondență în modelul Babelului, de Pieter Brueghel. Tolkien, la rândul său, descria Minas Tirith ca o cetate cu 7 incinte concentrice, protejate de ziduri de apărare, dezvoltată în trepte, cu un singur acces, inspirându-se din descrierile lui Herodot raportându-se la orașele fortificate. Autorii criticii Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings, Steven Woodward și Kostis Kourelis, remarcau în analiza surselor din spatele LOTR: „Minas Tirith este o arhitectură fantastică, un tort de nuntă istoricist, cu o luminozitate italiană. Orice formă posibilă din Evul Mediu până în Renaștere este îndesată într-un oraș care se ridică piramidal”. Într-o apologie a compoziției concentrice stratificate, marea majoritate a modelelor create sunt încununate de clădirea reprezentativă (biserica-palat), în punctul piramidal maxim, Minas Tirith și Edoras nefăcând excepție. Consecvent stilului arheologic și desenelor lui Alan Lee, Jackson recreează interiorul palatului-catedrală din Minas Tirith prin reminescențele Bisericii San Lorenzo și ale Catedralei din Siena9. Armonia și estetica Renașterii italiene timpurii devin baza stilistică a tipologiei interioare, expresie a celei mai înalte forme de civilizație. Complementar, alte expresii, cum ar fi cea a vernacularului din Shire și a arhitecturii nordice din Edoras, reflectă o civilizație pură, autentică, la o scară familială, intimă. Aglomerarea stilistică se manifestă frecvent sub forma eclectică, o exacerbare a valorii de reprezentare. Abundența formelor arhitecturale nu mai susține un traseu în sensul parcursului de la Delphi, devine uzanță estetică, specifică ecletismului secolului al XIX-lea târziu. Stilul arheologic al lui P. Jackson traduce istoria în sensul timpului trecut, al materialelor îmbătrânite, al ruinelor orașului Osgiliath, cu trimitere directă către Piranesi și percepția romantică a vestigiilor Romei Antice. Tot în ruină, Mordor este starea ultimă a arhitecturii într-un echilibu static precar, cu arcele incomplete, expresie a forței distructive a lui Sauron. Jocul contrastelor, al stilurilor echilibrate, statice și elansate, al arhitecturii formelor primare și al ecletismului aglomerat, al cromaticii luminoase/întunecate contribuie la definirea tipologică arhitecturală prin raport și, respectiv, ajută coerența cinematografică. Partea centrală a trilogiei - Cele Două Turnuri - eșuează în a relua același contrast și, ca atare, Jackson a fost acuzat de lipsa de adâncime a modelelor create. Pe de altă parte, cadrele arhitecturale, așa cum reies din literatura lui Tolkien, reflectă clar acuza adusă construcțiilor ambițioase, polemica antiindustrială și regăsirea în spațialitatea privată. Scara intimă exclusivă în Shire lipsește din punct de vedere al interpretării cinematografice a lui Jackson, în sensul în care Minas Tirith este un oraș gol, lipsit de locuitori. Lipsa de adâncime a construcțiilor, de care este acuzată versiunea cinematografică, rezidă și în determinarea strictă a celor patru categorii conform considerentelor estetice. Pe de altă parte, coerența stilistică se transpune în scară, material, culoare, determinarea specifică, transformând construcțiile în adevărate unități tipologice. Specularea caracteristicilor, amplificarea lor, determină acea transformare iconică pe care o remarcăm și în cazul Las Vegasului, unde Jackson speculează imaginea arhitecturală în sensul acelui Yes is More10 exprimat critic de arhitectul contemporan Bjarke Ingels. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 2/2013 al revistei Arhitectura |

| Note:

1. Pallasmaa, Juhani - The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, U.K., 2011. 2. Crișan, Ana Maria - extras și adaptare din Anagrama arhitecturii imaginare. Metamorphosis - reevaluarea paradigmei temporale în arhitectură. Teză de doctorat, Universitatea de Arhitectură și Urbanism „Ion Mincu”, București, 2012. 3. J(ohn) R(onald) R(euel) Tolkien - autor al romanului monumental elaborat într-un interval de 12 ani. Primele ediții au apărut între 1954-1955: The Fellowship of The Ring: Being The First Part of The Lord of The Rings (Frăția Inelului), George Allen & Unwin, London, 1954; The Two Towers: Being The Second Part of The Lord of The Rings (Cele două turnuri ), George Allen & Unwin, London, 1954; The Return of the King: Being The Third Part of The Lord of The Rings (Întoarcerea regelui), George Allen & Unwin, London, 1955. Cf. împărțirii strict editoriale și de marketing, volumele au fost considerate trilogie. 4. The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, regizor: Peter Jackson, scenariu: Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Peter Jackson, după o nuvelă de: J.R.R. Tolkien, productie: New Line Cinema, WingNut Films, The Saul Zaentz Company, 2001. Abreviere: LOTR. 5. Cf. Mathijs, Ernest; Pomerance, Murray (ed) - From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 6. Haase, Donald (ed) - The Greenwood Encyclopedia Of Folktales And Fairy Tales, Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., e-book, 2008, p. 977. 7. Woodward, Steven; Kourelis, Kostis - „Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings”, From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Ernest Mathijs, and Murray Pomerance. (ed), New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 8. Alan Lee, apud Steven Woodward and Kostis Kourelis, în „Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings”, cf. Ernest Mathijs, and Murray Pomerance. (ed), From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 9. Conform observațiilor stilistice ale lui Steven Woodward and Kostis Kourelis în „Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings”, From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Ernest Mathijs, and Murray Pomerance. (ed), New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 10. Ingels, Bjarke - Yes Is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution. Köln: Evergreen, 2009. |

| Lucrările pot fi consultate la adresa: http://www.beatricecoron.com/

InvisibleCities.html

Next Solo Exhibition: “Stories in a Thousand Cuts” - Ridgefield, CT Watershed Gallery, 2013 Group Exhibitions: “The ART of Storytelling: Tall Tales, Whoppers & TRUTH!” - American Visionary Art Museum, Baltimore, 2013 “Above the Din: Unstructured Conversations” - New Bedford, Massachussets, 2013 “Shadow and Light: Contemporary Papercuts” - Tinney Contemporary, Nashville, Tennessee, 2013 “Papercuts”- Eleanor D. Wilson Museum, Roanoke, Virginia, 2013 “Festival Textile 2013” - Rosny-sur-Seine, France, 2013 “The First Cut”- Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham, UK, 2013 Galleries: Muriel Guépin gallery, 83 Orchard Street, Manhattan Tabla Rasa, Gallery 224 48th Street, Brooklyn Recent publications featuring Beatrice Coron art: “Art Fragments 4” <http://www.magcloud.com/ browse/issue/397689> “Playing with Paper” <http://books.google.com/books/ about/Playing_with_Paper.html? id=nzIq7HBNkvQC> “1000 Artists’ Books” <http://www.hamiltonbook.com/ Art-Books/1000-artists-books-exploring-the- book-as-art> “Paperworks 1” by Sandu publishing Art & Métiers du Livre n°291 <http://www.art-metiers- du-livre.com> TED : “Stories cut from Paper” http://www.ted.com/talks/ beatrice_coron_stories_cut_from_paper.html Animation trailer: “Daily Battles” <http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=6goUp45k-Lk> Upcoming workshops and talks: Macalaster College, Minneapolis. April 17, 7- 8:30 p.m. <http://www.macalester.edu> Minnesota Center for Book Arts, Minneapolis. April 20-21 <http://www.mnbookarts.org/workshops/ adult.html> ANE, Bennington, Vermont. July 27- August 3, 2013. <http://mart.massart.edu/ane> Denver Botanical Gardens, Colorado. Lecture November 6, November 8-10. <http://www.botanicgardens.org/ programs/classes/school-of-botanical-illustration> |

|

The author thanks artist Beatrice Coron for her kind support in illustrating the article. PAPER CUTTINGS: BEATRICE CORON PICTURE CREDITS: ETIENNE FROSSARD |

| THE IMAGINARY ARCHITECTURAL DEPICTIONS |

| “The human mind is capable of forming mental images of things not actually present. The faculty of conceiving the images is (or was) naturally called Imagination. But in recent times, in technical not normal language, Imagination has often been held to be something higher than the mere image-making, ascribed to the operations of Fancy (a reduced and depreciatory form of the older word Fantasy); an attempt is thus made to restrict, I should say misapply, Imagination to «the power of giving to ideal creations the inner consistency of reality».”

J.R.R. Tolkien “FANTASY”, “On Fairy Stories” Presented to Charles Williams, Clive Staples Lewis (ed.). Oxford University Press, London, 1947 |

| THE ICONIC CONSTRUCTION BETWEEN THE HISTORICAL AND THE FANTASTIC DIMENSION

„WHAT THE PAST AND THE FUTURE HAVE IN COMMON IS OUR IMAGINATION, WHICH CONJURES THEM...”1 (JUHANNI PALLASMAA) The imaginary worlds embody architecture as the image of time - a time captured in-between the reality of the unique identity of the modern human and his postmodern multiple definitions. The built frame of the tales is the scenery that contextualizes and induces a fantastic size; it is the visual landing that articulates “the encounter of the world and the human mind”. It addresses the viewer through the sum of the familiar, recognizable elements, where the total amount of the specific features represents tradition. Watching the imaginary architectural process, we ask ourselves: what is the message of the imagined edifice? What is the ratio between tradition and identity? THE ICONIC CONSTRUCTION AND THE HISTORIC DIMENSION2 Under the narrative context, the fantastic dimension of J. R. R. Tolkien’s3 trilogy The Lord of the Rings is based on the projection of the “plot” as a story from another historical time. The assimilation of peoples, groups, and architectural styles, is a formal projection, typical for the cinematographic representation from LOTR4, supporting the scenery character within frame limits and determination. Director Peter Jackson used the iconic architectural elaborate process in order to amplify the epic conflict characteristic in Tolkien’s fiction, with a clear preference for the European stylistic determination. The four styles available in the cinematographic version develop the vernacular, naturalistic, grotesque and respectively archaeological architectures5, as Ernest Mathijs and Murray Pomerance remarked in From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. “Tolkien’s novel tends to construct more of a fairy-tale notion of the magical than do many of his successors in the genre. […] Ultimately, in its interest in history, politics, war, and the hero-king, The Lord of the Rings owes more to the epic and the romance than it does to the fairy tale.”6 In terms of history, the form attached to its function develops along the entire trilogy. Correctly, in terms of praxeology, the building material remains unchanged giving accordingly a geographically definable and functional identity. The peaceful universe of Shire is described by the British vernacular vocabulary. The comfort and the domestic atmosphere emerge from the pastoral habitat style implemented at a small-scale: bridges, water mills, developed on the ground floor or integrated into the landscape houses. The interiors of Bilbo’s house are consistent to the same lines of the vernacular - minimal interiors, horizontal ample spaces, circular voids. The filtered light of the interiors, the soft textures of wood and Earth, all compete in determining the atmosphere with a strong telluric focus. Complementarily, Elves’ universe in Rivendell and Lothlorien, located in the Woods, relies on the stylistic reinterpretation of the late 19th century Art Nouveau, in its cosmopolitan Gothic-influenced form. Far from being an authentic mimicry, the vocabulary counts on the graphic-style structure, developing the idea of biomorphism - the houses are suspended on the tree-trunks. The filigree structures, the fluid language of the lines, the sinuous branches that dress up the buildings, concur towards the romantic conceal and the dematerialization specific for the psychedelic naturalism and Art Nouveau. Antithetically, the evil becomes the grotesque Gothic, with underground spaces, sharp angles and freezing interiors of so many examples: Isengard, Mordor, Barad Dûr, Minas Morgul, the Black Gate, the Mount Doom Entrance. The monumental is reinterpreted in terms of heavy and oppressive, chromatically boosted. In Middle Earth, the boundary between the natural and the manufactured dissolves into a tectonic oppressing gesture. A complete aesthetics, dedicated to torture and pain inflicting methods, is built based on Metal, recalling of G.B Piranesi’s series and the late Gothic proto-mechanics. The metallic mechanisms cinematographically transpose the 19th century reaction opposite to the revolution of the material, namely Tolkien’s repulsion against the cold material of the industrial revolution, similar to the negative reception of the Eiffel Tower in 1889. The heroic cities identify with the volumetric displacement and the colour of the white stone, assuming the remains of the archaeological style. The architectural frameworks are clearly distinguished in two categories - stone and wood (Nordic), with references to medieval monuments. The northernmost one, King Theoden’s Rohan, belongs to the second category, with traditional Scandinavian influences (the Viking fortress in the 10th century in Trelleborg) and Anglo-Saxon7. Minas Tirith and Helm’s Deep evoke Byzantine, Viking, Roman and early Gothic influences. We are witnessing a double interpretation of the concentric model of Babel: positively soared, white, with a planimetric geometry in a radial arrangement, versus a negative, Gothic, aggressive, under construction, apparently chaotic structure. The monumental is amplified following the typical procedures used in vast cinematographic scenes, where citadels are located in isolation. The most spectacular construction, Minas Tirith, is developed on the basis of the original description, “the equivalent of Rome or Byzantium”8 with a clear correspondence in Babel, by Pieter Brueghel. Tolkien, in turn, described Minas Tirith as a fortress with seven concentric enclosures protected by defensive walls, developed in stages, with a single access entrance, drawing its inspiration from Herodotus depictions referring to the fortified cities. The authors of the critical essay Urban Legend: Architecture critics in The Lord of the Rings, Steven Woodward and Kostis Kourelis, remarked in analysing the sources behind the LOTR: “Minas Tirith is a fantastic architecture, a historicist wedding cake, of an Italian limpidness. Any possible form, from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, is pressed down in a town built up in a pyramidal way”. In an apology to the concentric layered composition, the vast majority of the created models is completed in a maximum pyramidal point by the representative edifice: the Palace-Church; Minas Tirith and Edoras follow the same pattern. Consistent with the archaeological style and Alan Lee’s drawings, Jackson recreates the Interior of the Palace-Cathedral of Minas Tirith through the reminiscences of San Lorenzo Church and the Cathedral of Siena9. Harmony and aesthetics of early Italian Renaissance become the stylistic basis of inner typology, the expression of the highest forms of civilization. In addition, other expressions such as the vernacular in Shire and the Nordic architecture of Edoras, reflect a pure, authentic civilization, to a family, intimate scale. The stylistic agglomeration manifests itself frequently in an eclectic form, as an exacerbation of the represented value. The abundance of the architectural forms no longer maintains a trail within the meaning of the journey from Delphi, it becomes an aesthetic practice, specific to the late 19th century eclecticism. The archaeological style of P. Jackson translates the history in the sense of past time, of the aged materials, of the ruins of Osgiliath, with direct reference to Piranesi and the romantic perception of the vestiges of ancient Rome. All in ruins, Mordor is the latest condition of the architecture in a precarious, static equilibrium, with incomplete vaults, as the expression of Sauron’s destructive force. The game of contrasts, the balanced, static and soared architectural styles fulfilled in the primary forms versus the amassed eclecticism, the dark-light colour scheme, contribute to the typological definition of architecture through the report, and consequently help the cinematographic consistency. The middle part of the trilogy - The Two Towers - fails to resume the same contrast, and as such, Jackson was accused of lack of depth of the models created. On the other hand, the architectural frameworks, as specified by Tolkien in his literature, clearly reflect the accusation brought against ambitious constructions, the anti-industrial polemic, and the retrieve in the private spatiality. The exclusive intimate scale in Shire is missing from the point of view of Jackson’s cinematographic interpretation, as Minas Tirith is an empty town, devoid of inhabitants. The lack of depth of the constructions, charged with the film version, resides in the strict determination of the four categories according to aesthetic considerations. On the other hand, the stylistic coherence translates into scale, material, colour, specific determination, turning the buildings into real typological units. The characteristics are speculated and amplified, hence determining the iconic transformation noticed in Las Vegas case. Jackson speculates the architectural image following the Yes is More10 concept that is critically expressed by the contemporary architect Bjarke Ingels. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| Notes:

1. Pallasmaa, Juhani - The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture (Architectural Design Primer). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, U.K., 2011. 2. Crișan, Ana Maria - extracted and adapted from The Anagram of the Imaginary Architecture - Metamorphosis-Reassessment of the Temporal Paradigm on Architecture (Pd.D. Thesis) “Ion Mincu” Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism - Bucharest, Romania, 2012. 3. J(ohn) R (onald) R (euel) Tolkien - the author of a monumental novel written along 12 years. First editions were published between 1954-1955: The Fellowship of The Ring: Being The First Part of The Lord of The Rings, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1954; The Two Towers: Being The Second Part of The Lord of The Rings, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1954; The Return of the King: Being The Third Part of The Lord of The Rings, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1955. The volumes were considered a trilogy due to publishing and marketing policies. 4.The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, director: Peter Jackson, script: Fran Walsh, Philippa Boyens, Peter Jackson, after a J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel, production: New Line Cinema, WingNut Films, The Saul Zaentz Company, 2001. Abreviere: LOTR. 5. As per Mathijs, Ernest; Pomerance, Murray (ed) - From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 6. Haase, Donald (ed) - The Greenwood Encyclopedia Of Folktales And Fairy Tales, Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc., e-book, 2008, p.977. 7. Woodward, Steven; Kourelis, Kostis - „Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings”, From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Ernest Mathijs, and Murray Pomerance (ed), New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 8. Alan Lee, apud Steven Woodward and Kostis Kourelis, in „Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings”, cf. Ernest Mathijs, and Murray Pomerance (ed), From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 9. As per Steven Woodward’s and Kostis Kourelis’ stylistic remarks in „Urban Legend: Architecture in The Lord of the Rings”, From Hobbits to Hollywood: Essays on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings. Ernest Mathijs, and Murray Pomerance (ed), New York, NY, and Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006. 10. Ingels, Bjarke - Yes Is More: An Archicomic on Architectural Evolution. Köln: Evergreen, 2009. |

|

Lucrările pot fi consultate la adresa: http://www.beatricecoron.com/ InvisibleCities.html Next Solo Exhibition: “Stories in a Thousand Cuts” - Ridgefield, CT Watershed Gallery, 2013 Group Exhibitions: “The ART of Storytelling: Tall Tales, Whoppers & TRUTH!” - American Visionary Art Museum, Baltimore, 2013 “Above the Din: Unstructured Conversations” - New Bedford, Massachussets, 2013 “Shadow and Light: Contemporary Papercuts” - Tinney Contemporary, Nashville, Tennessee, 2013 “Papercuts”- Eleanor D. Wilson Museum, Roanoke, Virginia, 2013 “Festival Textile 2013” - Rosny-sur-Seine, France, 2013 “The First Cut”- Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham, UK, 2013 Galleries: Muriel Guépin gallery, 83 Orchard Street, Manhattan Tabla Rasa, Gallery 224 48th Street, Brooklyn Recent publications featuring Beatrice Coron art: “Art Fragments 4” <http://www.magcloud.com/ browse/issue/397689> “Playing with Paper” <http://books.google.com/books/ about/Playing_with_Paper.html? id=nzIq7HBNkvQC> “1000 Artists’ Books” <http://www.hamiltonbook.com/ Art-Books/1000-artists-books-exploring-the- book-as-art> “Paperworks 1” by Sandu publishing Art & Métiers du Livre n°291 <http://www.art-metiers- du-livre.com> TED : “Stories cut from Paper” http://www.ted.com/talks/ beatrice_coron_stories_cut_from_paper.html Animation trailer: “Daily Battles” <http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=6goUp45k-Lk> Upcoming workshops and talks: Macalaster College, Minneapolis. April 17, 7- 8:30 p.m. <http://www.macalester.edu> Minnesota Center for Book Arts, Minneapolis. April 20-21 <http://www.mnbookarts.org/workshops/ adult.html> ANE, Bennington, Vermont. July 27- August 3, 2013. <http://mart.massart.edu/ane> Denver Botanical Gardens, Colorado. Lecture November 6, November 8-10. <http://www.botanicgardens.org/ programs/classes/school-of-botanical-illustration> |

Dwarrowdelf. Extras din seria cinematografică _The Lord Of The Rings. _Producție, Copyright: New Line Cinema, Wingnut Films, The Saul Zaentz Company

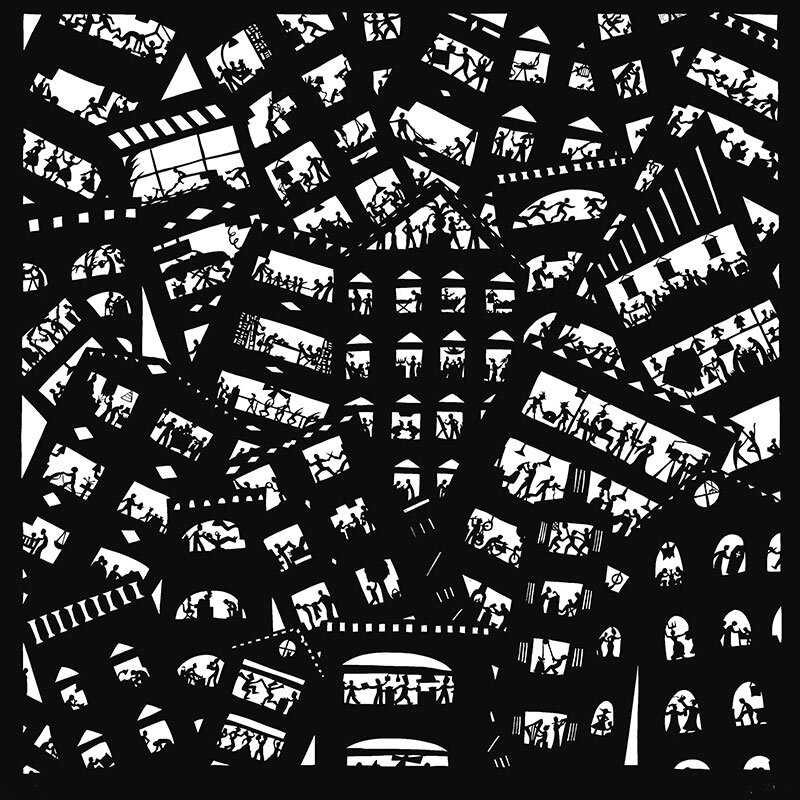

Chaos City, decupaj in Tyvek, 113 x 113 cm, 2010.

© Beatrice Coron

Fotografie:

Etienne Frossard

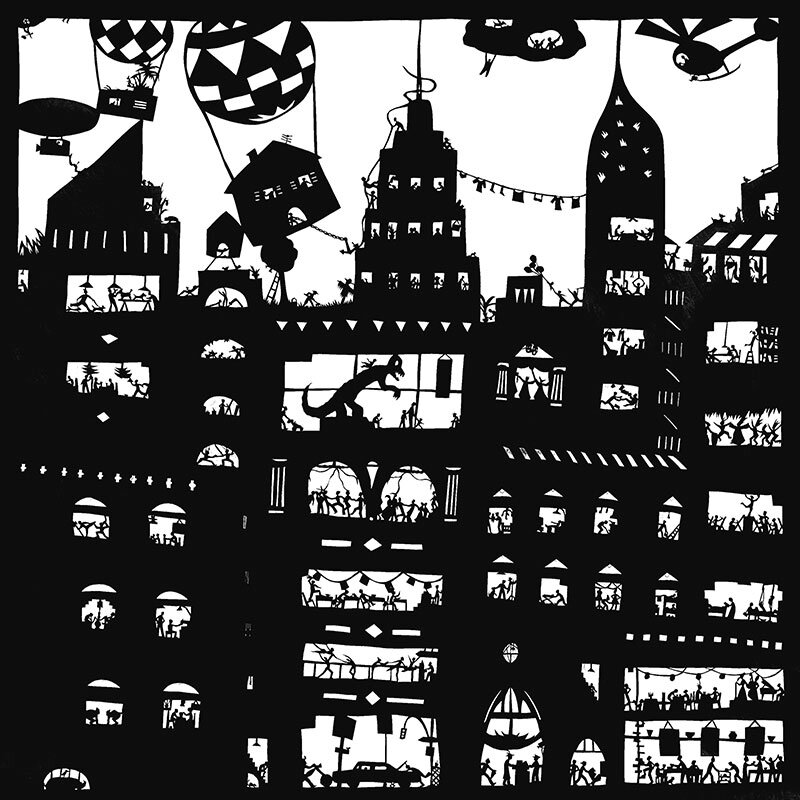

In the City, 115 x 115 cm, 2010. © Beatrice Coron

Fotografie:

Etienne Frossard