Interviu cu arhitectul Hagy Belzberg

Interview with architect Hagy Belzberg

| vorbitor principal invitat la expo-conferința GIS, București, 7-8 aprilie 2015 |

| Monica Lotreanu: Lucrarea cu care Biroul Belzberg Architects se face cel mai bine cunoscut în România, și cu siguranță și în lume, este Muzeul Holocaustului din Los Angeles (LAMOTH), inaugurat în 2010. American Institute of Architects (AIA) și alte instituții și organizații v-au premiat pentru această clădire, să menționăm numai Premiul de onoare pentru arhitectură acordat de AIA în 2014. Cum vi s-a încredințat această lucrare? A organizat Comunitatea Evreiască din Los Angeles un concurs, o selecție de propuneri sau ați fost invitat direct să proiectați clădirea muzeului?

Hagy Belzberg: Nu, a fost un comitet format din câteva organizații, printre care Departamentul Orașului pentru Parcuri și Recreere, care are în grijă toate parcurile publice din Los Angeles și se ocupă de recreere în parcurile publice, asta fiindcă muzeul este într-un parc public, Pan Pacific Park. A fost și reprezentantul districtului care deține parcul, și comunitatea care deținea Muzeul Holocaustului existent la acea dată – de fapt, Muzeul Holocaustului din Los Angeles este cel mai vechi muzeu de acest fel din Statele Unite, dar nu avea un sediu permanent, se muta de colo-colo, fiind un muzeu cu activitate educațională, dar și de cercetare academică (muzeul deține multe arhive). Aceste trei grupuri diferite au ales câțiva arhitecți și i-au intervievat, iar celor selecționați li s-a pus întrebarea care ar fi ideea lor de a pune un muzeu într-un parc public. Motivul amplasamentului în Pan Pacific Park era că acolo se afla un monument al Holocaustului, unde ei își țineau adunările anuale. Deci întrebarea lor era cum poți rezolva muzeul în parcul public, iar ideea noastră a fost de a nu avea o clădire măreață, eroică, ci una care conlucrează cu parcul, cu natura, fiindcă în Los Angeles nu avem mari spații deschise, avem multe clădiri de mici dimensiuni, dar nu parcuri mari. În opinia mea, parcurile fac parte din strategia urbană a protejării spațiilor publice. De aceea am avut ideea de a afunda parțial muzeul în teren și de a lăsa parcul să continue pe deasupra. Lor le-a plăcut ideea din multe perspective – din cea a parcului, pentru că îl pot folosi în întregime, din partea Comunității Evreiești și a Muzeului Holocaustului, fiindcă se crea oportunitatea unei narațiuni, a unei narațiuni foarte puternice. M.L.: Așadar, se pare că nu ați fost implicați în alegerea amplasamentului muzeului în parc... Care a fost relația cu clientul dumneavoastră pe parcursul proiectului? Puteți menționa pentru cititorii noștri problemele pe care a trebuit să le rezolvați? H.B.: Nu, nu noi am ales amplasamentul muzeului. A fost dificil să lucrăm cu mai mulți clienți deodată. Proiectarea și ceea ce noi numim aprobarea proiectului de a fi construit au durat cinci ani. Am făcut proiectul la început și apoi a trebuit să-l schimbăm ca să-i mulțumim pe toți. În acești cinci ani, trei directori ai muzeului s-au schimbat și a trebui să lucrăm cu toți. Au fost multe probleme legate de amplasament... dacă priviți fotografii vechi ale Los Angelesului, o să vedeți că se extrăgea petrol, așa s-a creat orașul, e mult petrol aici, iar amplasamentul este una din cele mai joase zone ale orașului, se numește un container care adună apele, astfel aveam în amplasament puțuri vechi de extracție a petrolului și apă stătătoare foarte murdară, apă contaminată. Dar aveam și mari pungi de gaz metan, care în Los Angeles e considerat foarte periculos, spunem că este gradul 5, cel mai ridicat. Am căutat mult suport tehnologic pentru a crea membrane pe măsură ce săpam în apă. Clădirea este proiectată ca o ambarcațiune, fără fundații, stă pe membrane care plutesc pe apă. Singura metodă de a nu lăsa clădirea să se ridice este greutatea, o masă foarte mare. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 2 / 2015 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| main keynote speaker in the expo-conference GIS, Bucharest, April 2015 |

| Monica Lotreanu: The most important work Belzberg Architects is known for in our country and internationally as well is the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust (LAMOTH). American Institute of Architects (AIA) and other institutions awarded you for this building, as to mention only the AIA Honor Award for Architecture in 2014. What was the way in which your office has been commissioned to do this project of the museum? Did the Jewish Community in LA organise a competition, a selection of proposals or did they address you directly an invitation to design the building?

Hagy Belzberg: No, it was a committee of several organizations that we call the City Department of Parks and Recreation that takes care of all the public parks in LA and the recreation use in the parks. There was the general county that owns the Pan Pacific Park, and there was the community that owns the existing Museum of the Holocaust – actually the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust is the oldest Holocaust museum in the United States, but they didn’t have a permanent home, they were moving around. It is an educational and scholarly research museum, they have a lot of archives, so scholars can go and research in the museum. Three different groups have chosen several architects to interview and they asked the selected architects what our idea would be given that the museum would be in a public park. The reason to be in the park is that they had the yearly gatherings nearby the Monument of the Holocaust, which is in the park. Their question was how do you deal with a museum in a public park, and our idea was not to have a grand building, a heroic building, but to have a building that works with the park, with the nature, because in Los Angeles we do not have a lot of open spaces, a lot of little buildings, but not big parks. In my opinion a park is part of an urban strategy to protect the open space. That is why our idea was to partially submerge the building and then allow the park to go over it. They liked the idea from many perspectives, because, from the park, you can use it, but for the Jewish Community and the Museum it created an opportunity for a narrative, a very heavy narrative. M.L.: It seems you didn’t have any involvement in choosing the site of the museum in the Park... What was the relation with your client during the design process? Can you mention for our readers the problems you had to solve in this project? H.B.: No, we didn’t choose the site. It was difficult to work with many clients. The design itself and what we call the entitlement to allow it to happen took five years. First we made the design and then we had to twist it every so often in order to make people happy. During these five years there were three different directors of the museum we had to work with. There were a lot of problems of the site… if you look at old pictures of Los Angeles you see they used to dig oil, there is oil in LA, the site is one of the lowest areas in LA, it is called a water containment area; so we had in the area old oil wells and heavy dirty water, contaminated water. But we also had large pockets of methane gas, which is very dangerous in LA, we call it level 5, which is the highest one. We had a lot of technological support in order to create membranes when we went down into the water. The building is designed like a boat, not with foundations; it stays on a membrane that floats on the water. The only way of not letting the building popping-up is the weight, a lot of weight. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |

Gores Grup Sediu/ Headquarters, Beverly Hlls, California, © Benny Chan;

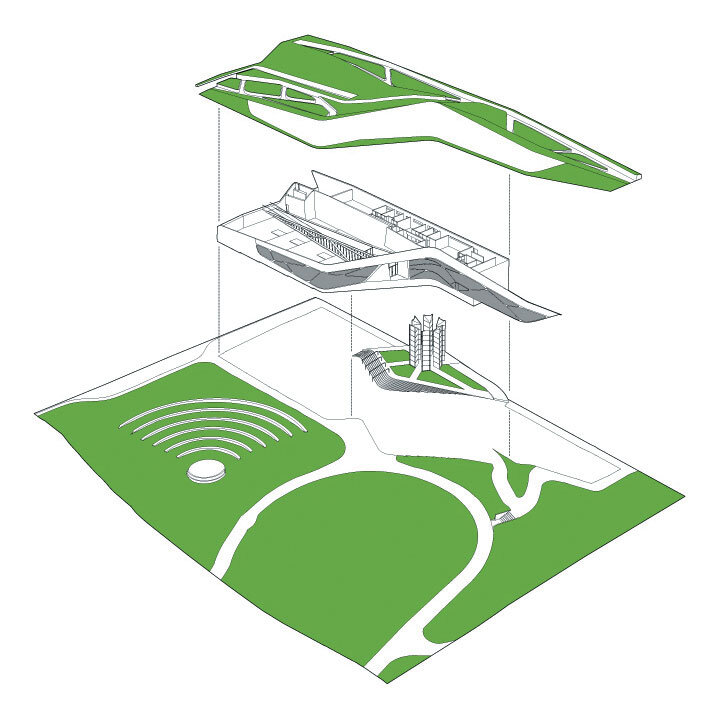

AMOTH, Axonometrie/ Axonometric scheme

LAMOTH, Expoziție/ Exhibition, © Iwan Baan;

LAMOTH, Vizitatori în camera monitoarelor/ Visitors in the monitor room, © Belzberg Architects

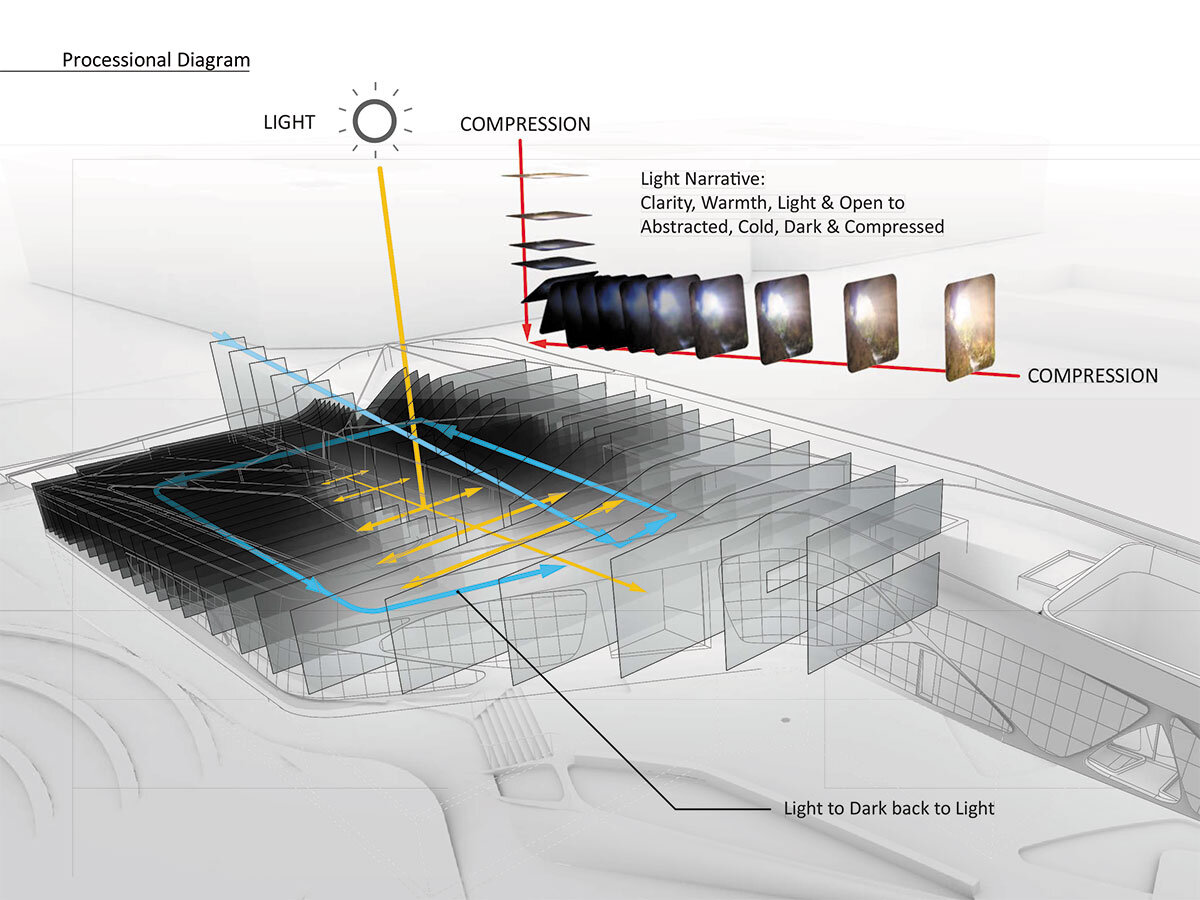

LAMOTH, Diagramă conceptuală/ Concept Diagram;

LAMOTH, Expoziție/ Exhibition, © Iwan Baan

LAMOTH, Hol intrare-ieșire/ Entrance/ Exit Hall © Iwan Baan;

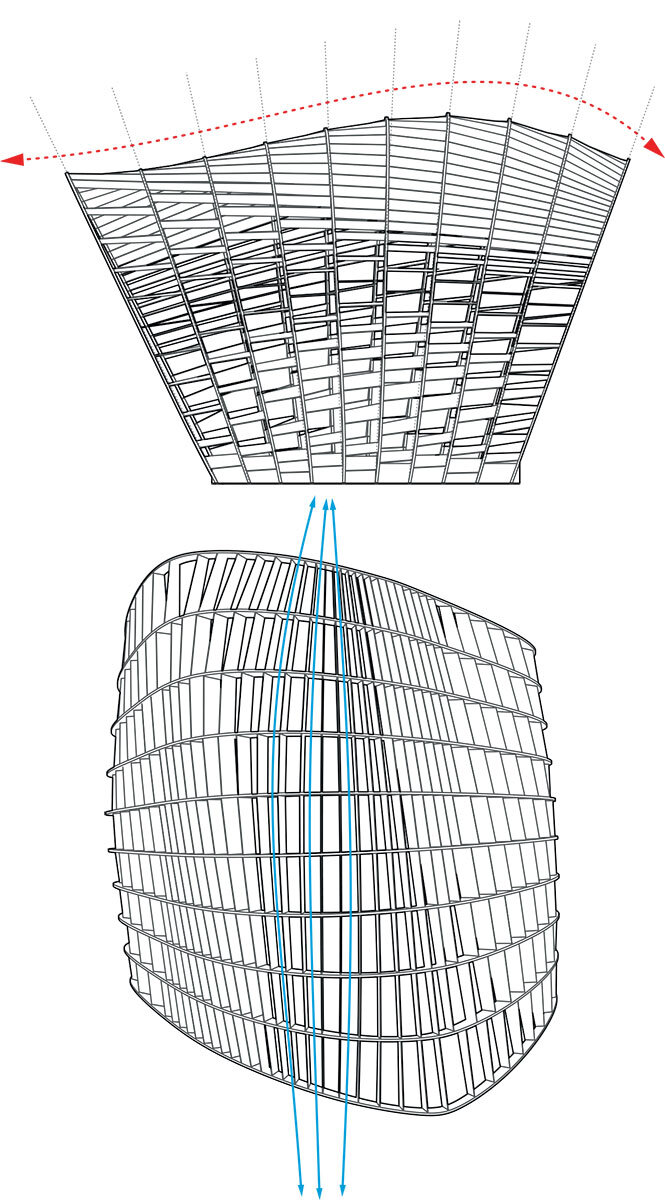

Kona Residence, Hawaii, Schițe pavilion intrare/ Entry Pavilion Drawings;

Camera mare/ Great Room © Belzberg Architects;

Pavilion intrare/ Entry Pavilion © Belzberg Architects