Turist pe front, selfie-uri la Bienală | Tourist on the Front, selfies at the Biennale

| În 2014 o eră se stingea și alta se năștea. Cel puțin așa se credea în momentul desemnării arhitectului chilian Alejandro Aravena drept curator al celei de-a cincisprezecea Bienale venețiene de Arhitectură. Omul momentului, omul arhitecților combatanți, în egală măsură însă și al establishmentului (ce altceva poate fi Premiul Pritzker recent primit decât o astfel de recunoaștere), primea sarcina de a pune în scenă cea mai importantă expoziție pe care câmpul arhitecturii, în ansamblul lui, îl oferă lumii. Desemnarea lui Aravena semnala, mai ales în zona cercurilor de stânga, o schimbare de paradigmă, o posibilă deplasare a discursului arhitectural din zona fluxurilor globalului înapoi spre teritoriile concrete și trăite ale localului. În 2014, era lui Rem apunea și odată cu ea elitismul și top-down-ul. Bottom-up-ul și corectitudinea politică erau aici. Un pic prea târziu am zice, pentru că Aravena nu este un stângist. Este suficient să-l ascultăm pentru a înțelege asta: „Problemele complexe și dificile necesită calitate profesională și nu caritate”. Momentul devine cu atât mai important cu cât conștientizăm felul în care realitatea lumii corecte politic este transformată astăzi de revirimentul brusc și neașteptat al populismului și chiar al fascismului, de falimentul aparent al multiculturalismului, de o evidentă și înfricoșătoare întoarcere la Realpolitik. Omenirea se află, neîndoielnic, într-un moment de răscruce. Arhitectura nu este scutită, la rândul ei, de aceste schimbări și ne putem întreba dacă Aravena nu este, la rândul lui, un populist, un agitator agățat de valul acestor schimbări, speculând tocmai criticile aduse câmpului arhitecturii. Aveau, oare, temele lui să răspundă acestor noi provocări sau aveau, din contră, să se adreseze acelorași idiomuri și discursuri pe care ultimul deceniu ni le-a servit, din păcate, până la refuz? Putea Aravena să se ridice la nivelul așteptărilor câmpului sau urma ca ambițioasa lui temă să fie, la rândul ei, trădată de formatul inadecvat și oarecum depășit al evenimentului. Din acest punct de vedere, Bienala este, de cele mai multe ori, o experiență, dacă nu frustrantă, atunci, în mod cert, epuizantă. Pentru toți cei ce-i trec pragul, ce o străbat la pas sau, din contră, o aleargă necontenit, chitiți să bifeze cu sârguință concepte, pavilioane, experiențe, de-a lungul unei vizite de două zile, răsfirați în spațiu între două puncte principale și o multitudine de expoziții secundare, Bienala se scrie, nu de puține ori, ca o supraîncărcare senzorială.Ce putem înțelege, așadar, din starea arhitecturii contemporane în urma unei simple vizite a Bienalei la trei luni de la marea ei inaugurare, când, ca simplii turiști, lipsiți de prea multe informații asupra dezbaterilor din jurul ei, am ales să o vizităm? Aceasta ne-a fost cheia de lectură. Ne-am asumat această poziție, considerând că acum, poate mai mult ca niciodată, era important ca arhitecții să transmită un mesaj clar și responsabil, mai puțin estetic și mai mult etic. Ce impresie ne-a lăsat?

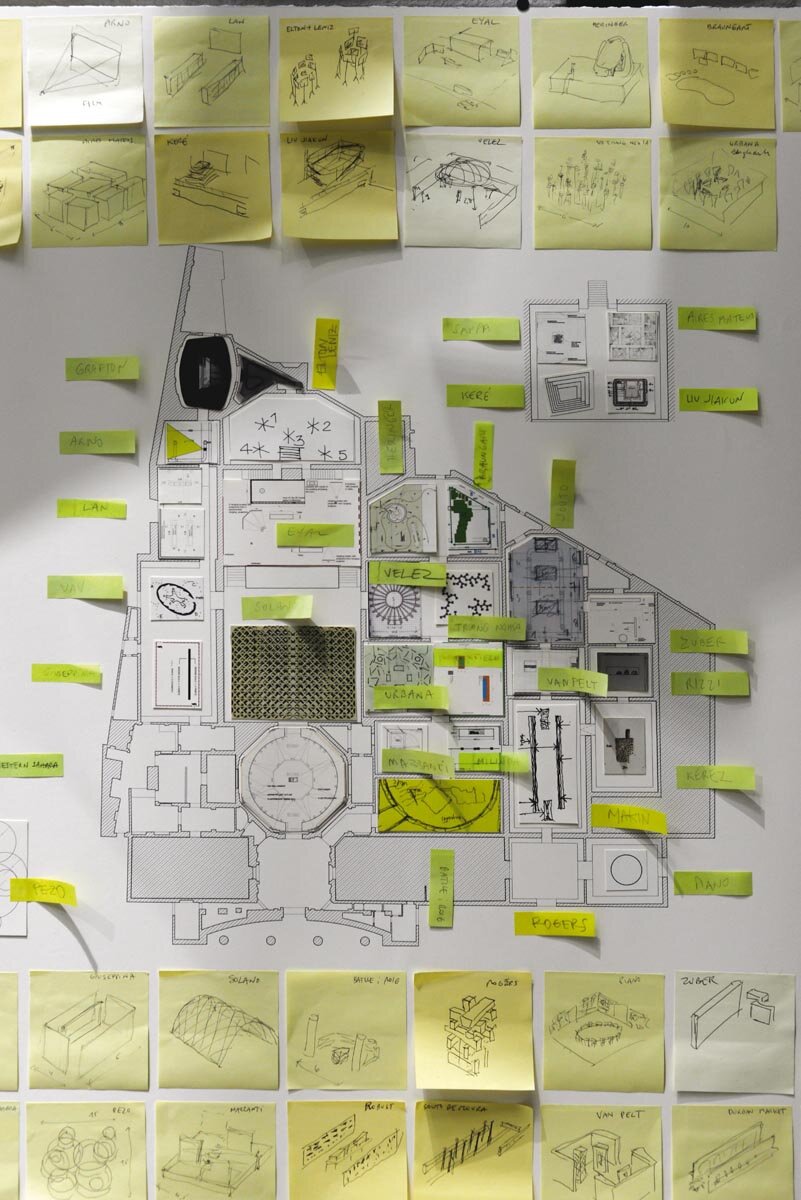

Pentru început să observăm, folosind chiar argumentul lui Aravena, că frontul este o condiție a lumii noastre, o luptă dialectică în jurul unor probleme globale precum calitatea vieții, inechitatea, locuințele, durabilitatea, periferiile, traficul, legislația, deșeurile, dezastrele naturale, infracțiunile, segregarea, poluarea, comunitățile și migrarea. Toate aceste chestiuni nu pot fi observate însă și înțelese decât din puncte de privire adecvate, sensibile în fața acestor necesități (astfel se explică afișul Bienalei cu a lui doamnă în capot căutând cu privirea, la distanță, liniile deșertului, de la înălțimea unei scări metalice). Fiecare dintre aceste teme este un front. Fiecare front – în disperată nevoie de trupe și resurse. Ce fel de trupe? Arhitecți „buni”. Exact așa ne spune Aravena într-o declarație ușor fariseică, însă plină de certitudini, ce-i încheie argumentul. Aici sunt numai arhitecți buni... iar noi, în mod sigur, suntem niște turiști norocoși. Ziua 1, Arsenale Ne-am început turul prin Bienală așa cum îl încep majoritatea arhitecților, pornind din Arsenal, considerând că acesta este locul în care tema e cel mai bine reprezentată spațial. Aici am trișat oarecum, deoarece știam că, tocmai prin configurația lui, Arsenalul are o abordare mai didactică ce permite o construcție graduală a argumentului, fiind astfel diferit de colecția aleatorie de săli a Pavilionului Italiei din Giardini. Nu știm însă dacă aceasta a fost și intenția lui Aravena. Odată intrat în prima sală, vizitatorul este întâmpinat de ceea ce pare a fi o instalație de artă conceptuală realizată printr-o atentă redefinire a planului tavanului. Acolo, deasupra capului, o rețea densă și apăsătoare de profile de gipscarton aduce spațiul la dimensiunea omului, într-o asemenea măsură încât toată greutatea și încărcătura simbolică a spațiului e așezată pe umerii vizitatorilor. Gestul lui Aravena subliniază nevoia de a recicla, toată încăperea fiind construită din materiale recuperate din Bienalele anterioare. Scenografia nu se poate debarasa însă de plasticitatea gestului – profilele par noi, fără fir de praf, fără amprente, nefolosite, iar deformările sunt toate în aceeași zonă. Arhitecții știu cum arată un profil recuperat… Etică 0 – Estetică 1. Schițele conceptuale pe care Aravena le prezintă pe lateralele acestui spațiu nu ajută nici ele. Par, mai de grabă, a trăda adevăratele motivații ale curatorului care, covârșit parcă de ideea organizării Bienalei, se surprinde într-un veritabil selfie alături de colaboratorii lui: așa am făcut noi Bienala. La rândul lor, schițele nu par a fi decât produsul unor decizii pure de design. Dar, pentru că suntem turiști, ne lăsăm convinși de toată această punere în scenă și alegem să ne mântuim de păcate în aura altfel cool a sălii. Trebuie să reciclăm! Să mergem mai departe. Primele săli sunt un puzzle. Expoziția debutează cu instalația, extrem de grăitoare, a biroului Al Borde, ce discută pe marginea valorii reale a proiectelor în termeni de timp, bani, dar mai ales de energie personală investită, ținând seama de dimensiunea, amplasamentul geografic, funcția și misiunea socială a proiectului, continuă didactic cu materialitățile reciclate aduse de Wang Shu direct de pe șantierul Muzeului Național din Fuyang, contemplă lumea tactilă, dar mai ales olfactivă a iurtei mongole reimaginate în proiectele de cercetare aparținând grupului Rural Urban Framework în colaborare cu Universitatea din Hong Kong, pentru a naufragia, în final, în etalările neinspirate ale biroului rus Bernaskoni și în blocurile de beton exagerat de monumentale ale biroului marte.marte. Sincer vorbind, dramatismul modelului imaginat de Bernaskoni, ce prin structura spațială de matrioșka sugerează nu participarea, cât simbolismul relațiilor de putere – cine este înăuntru și cine este afară – destabilizează sala într-o asemenea măsură, încât celelalte exponate aproape că dispar. Întrebați orice turist cu o cameră de fotografiat în mână. Din păcate, nu este singurul proiect care are acest efect: proiectul Punta della Dogana, al lui Tadao Ando, fiind un alt exemplu în acest sens. Fascinant ca design, dar controversat prin demers, proiectul este salvat doar de calitatea intrinsecă deja oricărui gest arhitectural făcut de Tadao Ando. Prezentarea proiectului însă alunecă fără voia ei într-o zonă artificial idilică. În fapt, ea este chiar pe linia frontului trasată intre Ando și Veneția. Ceea ce ne este prezentat sub forma unei povești de dragoste nu este, în fapt, decât o declarație formală, albumul cu poze mincinoase al familiei disfuncționale, atent pus spre văzul lumii doar de una dintre părți, locul fiind altfel presărat cu nenumărate mesaje de gherilă anti-Ando. Și pe bună dreptate. Văzând macheta coloanelor din beton pe care Ando urmează să le ridice în fața vechii vămi a Veneției mai că îți vine să semnezi o petiție. Oare ce s-o fi întâmplat cu frumosul Băiat cu broască al lui Charles Ray? Expoziția cunoaște o anumită revigorare atunci când încearcă să evite aceste controverse axându-se în schimb pe mijloacele prin care limbajul arhitectural poate fi redefinit tocmai de o anumită insuficiența a resurselor. Acest limbaj angajant social nu este lipsit de semnificații: poetice – instalația realizată de Transsolar (Mathias Schuler) împreună cu Anja Thierfelder, ce subliniază rolul luminii în constituirea imaterialului – sau tehnice – căutările formale ale Grupului de cercetare Philippe Block, din cadrul ETH Zürich, ce subliniază rolul materialului, dar și beneficiile designului computațional în edificarea construcțiilor experimentale de cărămidă, nămol sau lut. Cele două spații funcționează în tandem și constituie, probabil, apogeul întregii expoziții, ele făcând referire la ceea ce ar trebui să fie limbajul arhitectural într-un viitor construit cu ajutorul unor resurse finite. Tema este reluată în sălile următoare, în cadrul pavilionului la fel de interesant, chiar dacă ușor didactic, al biroului Anupama Kundoo Architects, care discută calitatea plastică a materialelor prefabricate moderne realizate, de această dată, din resurse naturale biodegradabile, precum și în instalația informativă a lui Hugon Kowalski și Marcin Szczelina, care documentează puțin cunoscutul avânt pe care a luat-o în India economia informală de reciclare a deșeurilor. Între aceste prezentări se inserează proiecte de mai mică anvergură, care pot fi multe dintre ele, din nefericire, trecute cu vederea,din cauza ambiguității formelor de prezentare. Ele fie aleg să își transmită mesajul sub forma unor prezentări video (cine are, în fapt, timp pentru a viziona așa ceva, având în vedere timpul limitat?), fie să se piardă în formele de discurs ermetice ale artei conceptuale. Și instalația Hilariopolis, a biroului ADNBA, este în acest sens, din păcate, parțial eșuată, în ciuda importanței subiectului pe care îl tratează. Echipa ADNBA a ales să vorbească despre oraș ca loc al memoriei copilăriei, al experienței formatoare, ca resursă narativă a propriilor proiecte, alegând să prezinte un fragment utopic al acestui oraș posibil. Un mash-up de vechi și nou, ce ne este înfățișat la persoana întâi, pentru că aici privitorul își asumă poziția naratorului, privind orașul din lumea acestuia, de la înălțimea apartamentului pe care îl ocupă. Macheta pusă în lumina reflectoarelor este însă atât de fotogenică, de minunată, încât transferă atenția de pe conținut și narațiune – calitatea îndoielnică a proiectelor imobiliare recent realizate din România – pe conținător și pe broderia bizantină ce îl definește. În ciuda acestui fapt, dacă e să judecăm după ce am văzut cu ochii noștri, a fost unul dintre cele mai fotografiate obiecte de la Arsenal. În mod evident, o serie de expuneri au operat la scara orașului sau chiar a teritoriului. Comparând proiectele top-down ale statului wellfare cu procedurile anarho-sindicaliste de tip DIY ale prezentului, BeL Sozietät für Architektur își imaginează un scenariu de creștere, conform căruia grupurile de imigranți așezate în spațiul Germaniei pot fi ajutate să își construiască propriile cartiere utilizând manuale și modele standardizate. Mai departe, Grupo EPM, își prezintă proiectele din Bogota, în timp ce Rahul Mehrotra și Felipe Vera documentează urbanismul efemer sau, mai bine-zis, fenomenul conurbațiilor temporare de tip „pop-up”, apărute în întreaga lume din varii motive: migrație, schimburi, festivaluri, catastrofe. Discuția pornită de toate aceste expuneri este continuată în afara Arsenalului, în expoziția „Report from the Cities: Conflicts of an Urban Age” (Reportaj din orașe: conflictele unei ere urbane), ce oferă o privire de ansamblu asupra provocărilor ce ne așteaptă: de la suprapopulare și creștere necontrolată, la lipsa spațiului, dar mai ales a resurselor fizice necesare pentru susținerea acestei dezvoltări. Vă întrebați ce părți din lume se extind cel mai rapid? Poate ar fi mai important să observăm care sunt sistemele politice și formele de guvernare ce stau în spatele acestor mega-orașe deja suprapopulate? Expozițiile din Arsenal continuă cu o combinație de pavilioane naționale și expoziții realizate de birouri invitate. Din rândul celor din urmă, selecția este aiuritoare, s-ar putea spune chiar neinspirată, și surprinde lucrări de Kengo Kuma, Ensamble Studio sau Peter Zumthor. Exponatele nu contribuie cu nimic la tema Bienalei, fiind mai degrabă ca o bilă de plumb la piciorul lui Aravena. Ce altceva poate fi gestul făcut de Ensamble Studio, care a ales să își prezinte ultimul proiect de landscape art, în care literalmente toarnă beton peste gropile deșertului numai pentru a crea ARTĂ. Doar Shigeru Ban mai reînzestrează cu semnificație această selecție, alegând să prezinte cu subtilitate urmele de viață biologică apărute de-a lungul celui mai vechi front real al lumii, și anume zona demilitarizată dintre cele două Corei. Expoziția din Arsenal se încheie glorios cu patru machete de tip mock-up: cea a organizației ORG Permanent Modernity care investighează, prin intermediul panourilor prefabricate din beton, puterea limbajului arhitectural de a opera încă simbolic cu formele platonice; excelenta școală plutitoare realizată de biroul NLÉ care a și câștigat Leul de Argint; interpretarea la fel de interesantă a spațiilor prefabricate propusă de biroul SUMMARY sub forma modulului din beton care se poate extinde în manieră metabolică; și, la final, bolta experimentală cu dublă curbură realizată de Norman Foster în colaborare cu Institutul Federal de Tehnologie ETH, din Zürich, pentru proiectul Future Africa al Universității EPFL, din Lausanne. După estetica formală și oarecum lipsită de conținut afișată de Zumthor, spre exemplu, aceste exponate au avut suficientă putere pentru a ne oferi o imagine asupra a ceea ce poate fi arhitectura responsabilă a viitorului. Ea se scrie formal, cu materiale simple, abundente, ce sunt puse în operă, nu de puține ori, folosind tehnici de construcție tradiționale, augmentate digital. Forma urmărește nu doar funcția, ci și nevoia și resursa. În concluzie, prima zi a fost oarecum dezamăgitoare și neconvingătoare. Felul în care au fost dispuse părțile a părut confuz. Ca turist am putut, într-adevăr, să dobândesc mai multe cunoștințe cu privire la diferitele practici utilizate în prezent pe mapamond, dar numai acolo unde acestea erau explicate suficient de didactic. Chiar și așa, a durat foarte mult până am parcurs toate exponatele. Deși am folosit cele opt ore disponibile, pot să spun că am fost mereu pe fugă și am reușit chiar să ratăm o expoziție în totalitate, „A World of Fragile Parts” (O lume din bucăți fragile). Spre finalul traseului eram deja epuizați. Ajuns în fața pavilionului final, cel al Italiei, pur și simplu, nu-ți mai pasă; tot ce vrei este să-ți iei un spritz, pe un canal venețian și să te uiți la marea de oameni care se mișcă în toate părțile: oameni ai lumii. Sunt încă multe de învățat despre calitatea vieții, inegalitate, locuințe, durabilitate, periferii, trafic, nerespectarea legilor, deșeuri, dezastre naturale, infracțiuni, segregare, poluare, comunități, migrare privind străzile și piețele Veneției decât în orice alt eveniment de acest fel. Zi sau noapte, Veneția le are pe toate. Poate a doua zi avea să fie mai bună. Ziua 2, Giardini Pentru a doua zi am vrut să concluzionăm bătăliile lui Aravena, astfel încât, așa cum era firesc, am ales să pornim incursiunile în Giardini cu pavilionul Italiei. Dacă Arsenalul a fost, în mare măsură, o experiență didactică ce a evidențiat tehnici, metode și procese, așa cum ne și așteptam, de altfel, aici, în pavilionul Italiei, accentul urma să fie pus pe arhitecți, pe povestea oarecum eroică a fiecăruia dintre ei. Iar în unele cazuri, dacă nu chiar în majoritatea lor, aceste povești meritau să fie spuse și regizate astfel, dar, să nu mă înțelegeți greșit, au fost, din nefericire, și expuneri care păreau a se referi mai mult la promotorii lor, arhitecții, decât la orice altceva. Pavilionul Giardini te întâmpină cu imaginea impresionantă a bolții din cărămidă armată realizată de Gabinete de Arquitectura. Proiectul este, în primul rând, un omagiu adus puterii arhitecturii, capacității spațiului arhitectural de a ne uimi necontenit, chiar și prin cele mai simple materiale și forme. Instalația, care a câștigat Leul de Aur pentru cea mai bună participare din expoziția Reporting from the Front, ne amintește de toate acele lucruri pe care le-am pierdut în favoarea tehnologiei: meșteșugul practicat cu artă și o anumită mentalitate ce ne permitea, până nu demult, să construim cu mâinile noastre, în afara regulilor sau a normelor impuse de producători și dezvoltatori. Din acest punct de vedere, instalația continuă argumentul prezentat de Sir Norman Foster, punând accentul pe acele resurse ce sunt la îndemâna oricui, în acest caz argila și nămolul, precum și pe modul în care ele pot fi transformate nu doar într-un material de construcție ieftin și rezistent, ci și într-o formă de expresie a prezentului. Evident, nimeni nu își închipuie că bolta prezentată de Gabinete, așa goală cum este ea, are vreun alt scop în afară de acela de a prezenta frumusețea inerentă a acestor structuri. Nimeni, cred, nu se așteaptă să construiască astfel de case la scară mare. Proiectul expus prezintă, totuși, o anumită ambiție dincolo de gestul său expresiv. El constituie apogeul unei practici care s-a bucurat de apreciere mai ales în rândul oamenilor ce au folosit-o de-a lungul timpului. Nu este nici singurul proiect de acest fel, și aici trebuie să menționăm și alte proiect la fel de expresive prezentate în pavilionul Italiei, și anume spațiile din argilă realizate de Anna Heringer și Lehm Ton Erde Baukunst sau structurile tectonice din bambus realizate de Simón Vélez sau de Vo Trong Ngia Architects. Pe un front similar, dar de această dată operând la scară urbană, descoperim cercetarea lui Christian Kerez și Hugo Mesquita, ce abordează problema ordinii și dezordinii în favelele braziliene, sau gesturile reparatorii implementate de designworkshop : sa în aglomerata și improvizata principală piață agroalimentară a orașului Johannesburg, apărută spontan într-o joncțiune de autostrăzi, neterminate la finele anilor 2000. Ambele proiecte funcționează ca soluții de sus în jos pentru problemele apărute de jos în sus. Primul dintre ele studiază DNA-ul structurilor favelas, încercând să identifice tipare și modele pe care să le poată replica ulterior în mod ordonat, în timp ce al doilea aduce corecții asemenea unui chirurg care coase capetele rupte ale unei artere, reîntregind astfel structuri spațiale neterminate. Unul dintre puținele proiecte de la această Bienală care a abordat nevoia de a reconsidera arhitecturile deja existente a fost cel al biroului francez LAN, care și-a îndreptat atenția asupra blocurilor de locuințe moștenite din perioada modernismului târziu. Exercițiul lor începe printr-o atentă examinare a vieților subiecților puși în discuție, într-o manieră aproape voyeuristică, ce încearcă să abandoneze schema tipică a dezvoltatorului în favoarea unei abordări mai personalizate ce pune, astfel, accentul pe nevoi personale specifice. În mod similar, Richard Rogers și Renzo Piano adresează, la rândul lor, problema locurilor comune, readucând în prim-plan ideile de factură futurist metabolică ce le-au articulat discursul în deceniul 7. Tema patrimoniului recent este, din păcate, insuficient abordată pe parcursul Bienalei, cel puțin nu în cadrul conceptului curatorial al lui Aravena. În rest, de fiecare dată când accentul cade și pe prima lume, discuția tinde să alunece, de cele mai multe ori, spre simple decizii de lifestyle. Frugalul, reîntoarcerea temporară la natură, la o esență pierdută, par a fi temele puse în discuție de SANAA, birou ce, încercând să-și găsească pacea interioară după atâtea proiecte urbane, a ales să se purifice operând participativ pe o mică și izolată insulă a arhipelagului japonez. Într-un mod similar, Aires Mateus pare a vorbi doar despre propria-i căutare a frumuseții ideale. Ce altceva poate fi altfel fabulosul lor spațiu înecat în întuneric. Astfel, nu de puține ori, expoziția pare a fi o colecție de supereroi, fiecare dintre ei venind dintr-o altă lume, din alt oraș sau univers paralel, fiecare luptând împotriva propriilor „răufăcători”, făcând uz de superputeri specifice, unele mai spectaculoase decât altele. Unii au ales să se prezinte prin proiecte tipice „de sus în jos”, realizate în etapa târzie a carierei lor, expuse aici, mai degrabă, pentru calitatea lor compensatorie (de exemplu, lucrările lui David Chipperfield sau ale lui Norman Foster, din Africa). Alte proiecte se scriu ca manifeste veritabile ale unor căutări susținute și de durată ale unor arhitecți ce operează participativ, din mijlocul propriilor comunități. Cu toate acestea, nu există o linie de demarcație clară între actele autentice de eroism și cele care sunt doar o spoială menită să epateze. Vizitatorul este, astfel, păcălit, el acceptă imaginea de grup a acestor cavaleri înfășurați în mantie albă. Albă precum camera probelor (The Evidence Room), ce așteaptă în liniște în chiar miezul acestui construct imagistic. Acolo, în mijlocul acestei lumi de supereroi, descoperim cu stupoare o bombă cu ceas ce vine din trecut încă ticăind. Aici, un cu totul alt gen de erou alb ne stă în față, un antierou, înarmat cu mijloace de distrugere simple, dar eficiente. Ușa văruită, cu a ei clanță doar pe exterior, scara sprijinită instabil lângă ferestruica de verificare a carnajului, coloana dublă din sârmă de oțel utilizată pentru administrarea canistrelor de gaz, toate, banale prin formă, dar îngrozitoare prin conținut. Mașinării ale morții născute din obiectele vieții de zi cu zi, o ușă, o clanță, o scară, transformate prin ceea ce Hannah Arendt a denumit banalitatea răului. În varianta lor ultimă, perfecționată, coloanele de coborâre prin tavan a canistrelor de Zyklon B puteau asigura nimicirea rapidă a 2.000 de suflete în fiecare zi. Există numeroase dovezi în sală că toate aceste obiecte neînsuflețite, aceste instrumente, au fost planificate și concepute cu atenție de către cineva. Există, în primul rând, schițele trasate cu claritate și semnate toate de către arhitecți. Iar apoi, există și o fotografie. Stând în picioare lângă ofițerii lagărului de concentrare, în fața proiectului lor, baia comunală, arhitecții par niște oameni împliniți. Este poza lor finală, de recepție. Privitorului i se îngreunează în mod deliberat sarcina de a distinge trăsăturile acestor oameni. Ele pot fi observate numai prin examinarea atentă a reliefului filigranat al hârtiei albe, prin jocul deliberat de lumini și umbre care nu permite decât o idee vagă asupra modului în care toți acești „oameni” arătau. În esență, sunt toți la fel; arhitecți, ofițeri și funcționari ai lagărelor, tuturor le revine aceeași responsabilitate. Unii încă mai doresc să uite acest trecut, dacă nu chiar să îl nege cu totul, precum autoproclamatul istoric și contestatar al existenței Holocaustului, David Irwin. În fapt, toate aceste dovezi au fost adunate cu migală, documentate și recreate în machete 1:1 de către profesorul Robert Jan van Pelt și studenții săi, de la Școala de Arhitectură din Waterloo, tocmai ca o susținere împotriva procesului de calomnie pe care Irwin i l-a intentat istoricului american Deborah Lipstadt și Editurii Penguin Books. Lipstadt îl catalogase pe Irwin drept contestatar al holocaustului, iar acum acesta dorea să își apere teoriile. Până la final, s-a dovedit a fi cel mai complex exercițiu de arhitectură criminalistică realizat vreodată. Irwin a pierdut procesul. Contestatarii însă, cei care vor să uite istoria, cei care vor „să facă din nou lucrurile mărețe”, sunt încă mulți, iar 2016 este, într-un fel, anul revenirii lor în scenă. Unii dintre ei sunt cu siguranță arhitecți, aici nu suntem diferiți, demografic vorbind, de restul lumii, și să nu uităm că pentru ei răul este banal, o simplă sarcină ce trebuie îndeplinită. Expozițiile exterioare Am părăsit Pavilionul Italiei prin lumina albă a acestor revelații, nu însă fără a vizita și ultima sa expoziție-mărturie, cortul de refugiați realizat de Manuel Herz împreună cu Uniunea națională a Femeilor Sahrawi. Cortul, ce străjuiește chiar intrarea pavilionului Italiei, poate trece neobservat pentru cea mai mare parte a vizitatorilor, tocmai datorită banalității lui. Înăuntru însă tapiseriile de mari dimensiuni, țesute manual chiar de femeile Sahrawi, spun o poveste mai mult decât relevantă pentru tema Bienalei, pentru că aici suntem din nou în fața unei povești spuse la persoana întâi, direct de pe front. Aici, femeile și-au țesut propria poveste, surprinzând hărțile propriului exil din calea războiului civil vest-african, hărțile taberelor de refugiați. Ele vorbesc despre noul lor cămin, cortul nomad care, sub aceste auspicii, devine o casă împământenită artificial în noile teritorii ale refugiului. Dacă ați ratat acest pavilion, ați ratat Bienala, iar noi am fost foarte aproape să îl ratăm. Din perspectiva noastră, aproape că nici nu exista acolo, îl vedeam, dar nu îl conștientizam. Și ce altceva era acest pavilion dacă nu tocmai o lume în mișcare, imaterială, textilă, pierdută printre structurile împământenite și monumentale ale lumii dezvoltate, un cort printre clădiri, un artefact al frontului real amplasat lângă reprezentările abstracte ale unor fronturi imaginate. Lumea dezvoltată nu este însă lipsită de probleme. Cu puține excepții, pavilioanele naționale au adoptat o viziune pozitivistă față de o serie de probleme ce, în ciuda particularităților contextuale, pot fi catalogate a fi universal valabile primei lumi. Printre acestea putem nota: discuțiile pe marginea definirii unei posibile noi estetici născute dintr-o asumare eroică a insuficienței resurselor (Belgia), analiza repercusiunilor încă vizibile ale colapsului sistemic al anului 2008 (Spania, SUA), evidențierea problemelor sociale și politice create de noile valuri de imigranți ce își caută casa în spațiul european (Germania, Austria), problema locuințelor și a costului vieții (Anglia, Franța), încrederea aproape religioasă în tehnologie și în soluțiile pe care industriile cunoașterii le pot oferi spațiului construit (Israel), aprecierile pe marginea rolului arhitectului în societate (Ungaria, România), radiografiile unor teme-program aflate în continuă schimbare (Australia, țările nordice), încercările de reinterpretare a istoriei recente și a artefactelor sale construite (Rusia, Cehia, Slovacia). Leul de Aur a fost acordat pavilionului Spaniei, „Unfinished” (Neterminat). Curatorii au ales să evidențieze efectele pe care criza economică prelungită le-a avut asupra sectorului locativ din Spania, utilizând cu precădere limbajul fotografiei. Sala principală utilizează exclusiv acest mediu, într-un exercițiu care seamănă în multe privințe, din punct de vedere al formei, conținutului și tipului de comentariu, cu proiectul Mândrie și Beton, realizat de Petruț Călinescu și Ioana Hodoiu. Imaginile prezentate înfățișează proiecte de infrastructură abandonate, loturi vacante și peisaje mutilate, dar, în special, case neterminate ce sunt totuși, în lipsa accesului la infrastructură, la cele mai de bază utilități, locuite. Sunt imagini care ar fi putut fi surprinse în oricare dintre dezvoltările suburbane ce au destructurat peisajul extravilan al orașelor românești. În fapt, prin extrapolare, aceste situații sunt intrinsec legate între ele. Bula de săpun spaniolă odată spartă a pulverizat nu doar șantierele Spaniei, ci și pe cele ale României. Astfel, pavilionul Spaniei face referire nu doar la peisajul andaluz sau galician, ci și la multe alte locuri, cum ar fi Maramureșul sau Moldova, indirect afectate. A doua parte a expoziției oferă soluțiile, printr-o expunere metodică și conștiincioasă a unor proiecte care au reușit să își ajusteze mijloacele și gesturile arhitecturale, adaptându-se astfel problemelor generate de criză. Această selecție prezintă, fără îndoială, o arhitectură de calitate, al cărei principal merit transpare tocmai din modul în care reușește să transforme insuficiența resurselor într-o opțiune expresivă, fidelă, în continuare, minimalismului iberic. În aceeași zonă a argumentației găsim pavilionul Belgiei, care mută însă atenția pe detalii și componente, pe acele elemente constructive ce, în ciuda banalității lor, se pot transforma sub bagheta arhitecților, cu bravură, în veritabile forme ale expresiei arhitecturale. Dar dacă pavilionul Spaniei se adresează vizitatorului într-un mod cât se poate de clar prin diagrame și fotografii, cel belgian rămâne eliptic fiind, mai degrabă, asimilabil artei sărace. Pentru un ochi neantrenat, detaliile expuse pot fi banale, eludând orice categorie estetică în sensul clasic. Este, poate, o recunoaștere onestă a faptului că, de cele mai multe ori, mediul nostru construit nu este decât forma unor nevoi, circumstanțe sau opțiuni economice. Un pic mai jos pe aceeași stradă, pavilionul Olandei stabilește o serie de conexiuni neintenționate cu cortul femeilor Sahrawi adus de Manuel Herz, oferindu-ne imaginea cosmetizată a taberei de refugiați văzută de acesta din perspectiva căștilor albastre olandeze, aflate în misiuni de menținere a păcii în mai multe țări africane. Amintindu-ne însă „reușitele” misiunilor de pace olandeze în Bosnia și, recent, chiar și în Africa, nu putem să nu notăm optimismul oarecum inadecvat al întregii expuneri, care fără să vrea readuce în prim-plan mitul eroului alb, mitul misionarului civilizator. Să mai spunem și că întreg pavilionul este scăldat într-o lumină albastru-neon, ce dă întregului o notă tehno-șic? O instalație la fel de „cool” este și spațiul-obiect pe care Christian Kerez îl propune vizitatorilor pavilionului Elveției. Structura prezentată ce ilustrează cu succes cele mai recente cercetări ale ETH în domeniul studiului formei, reușește să ofere întregului pavilion o atmosferă specific elvețiană, „venită parcă din afara acestei lumi”. Kerez, ce a avut ocazia să atace câteva din temele Bienalei în studiul pe Favelele din Sao Paulo, se concentrează aici pe emoția pură pe care forma arhitecturală ne-o poate transmite, un aspect altfel puțin abordat de celelalte expoziții din Giardini. Tema spațiului sensibil este reluată într-o anumită privință în pavilionul țărilor nordice unde vizitatorilor li se oferă pentru prima dată ocazia de a atinge, la propriu, deja legendarele grinzi lamelare ale lui de Svere Fehn. În interiorul pavilionului, o enormă piramidă din lemn ocupă cea mai mare parte a spațiului. Pe treptele ei, urmărind stratificația piramidei lui Maslow, vizitatorii, ce fie își trag sufletul, fie admiră structura de beton a tavanului, găsesc fișate cele mai relevante proiecte venind din spațiul nordic. Lângă ele, la baza piramidei, găsim zona de terapie. Aici, întins pe patul de terapie, turistului îi sunt prezentate problemele arhitecturii nordice, pentru că nordicii, fideli propriilor modele culturale, nu au știut să facă altceva decât să își ducă clădirile la psihanalist. În imediata vecinătate, Danemarca oferă, probabil, pavilionul ideal al oricărui turist, vizitatorul fiind efectiv înecat într-o mare de machete arhitecturale ce înfățișează ultimele proiecte de orientare socială ale acestei țări. Totul este însoțit de un material video dedicat cui altcuiva decât lui Jan Gehl. Pavilionul Rusiei este, din nou, opulent prin tehnologia utilizată, dar mai ales prin ideologia afișată. El vorbește despre nevoia Rusiei de a-și reconsidera perioada realismului socialist, încercând parcă să stabilească legături între iconografia pozitivistă, utopică a stalinismului și nevoile similare ale regimului putinist. Este, astfel, în mod evident, discursul cel mai consistent subvenționat de o ideologie de stat dintre toate celelalte prezentate în cadrul acestei Bienale. Să anticipeze el, oare, viitorul Bienalei? Prin comparație cu pavilionul Rusiei cu ai săi pereții acoperiți cu ecrane video și machete costisitoare, pavilioanele Germaniei, Angliei și Franței par insignifiante ca arie de cuprindere și resurse. Nu putem, totuși, să trecem la ele fără să menționăm că recent renovatul pavilion japonez se înscrie în lina cu care Japonia ne-a obișnuit la ultimele Bienale. De acesta dată, Japonia a pus în scenă birouri tinere ce operează în zona locuințelor sociale la scară mică. Pavilionul german, probabil printre cele mai ieftine, subliniază atât tema resurselor finite, cât și problema deșeurilor rezultate în urma acestei Bienale, oferind vizitatorului un spațiu ce este în cea mai mare parte gol. Povestea Germaniei este spusă prin afișe, diagrame și info-grafice afișate exclusiv pe pereții pavilionului. După cum era de așteptat, Germania și-a îndreptat atenția asupra problemelor imigrației, prezentând o serie de studii de caz ce au urmărit de sus în jos situația câtorva orașe, cartiere și chiar familii. Curatorii germani au ales astfel să nu vorbească despre nevoia de a construi, cât despre modul în care contexte deja construite se redefinesc astăzi prin nevoile noilor ocupanți, imigranții, punând accent atât pe condițiile spațiului lor locuibil, cât și pe cea a spațiului comunal, public. Într-o manieră similară, de cealaltă parte a parcului, pavilionul Austriei abordează, la rându-i, problema imigrației și modurile în care migranții ocupă ilegal spațiile unor clădiri de birouri nefolosite. Expoziția este construită la propriu în jurul câtorva familii de imigranți, cea mai mare parte a bugetului fiind consumată pe câteva intervenții arhitecturale ce au avut menirea de a le îmbunătăți acestor familii condițiile de locuit. Procesul este documentat fotografic, prin postere și un ziar disponibil gratuit. Pavilionul Marii Britanii abordează, la rândul lui, problema locuințelor, însă într-un mod specific Londrei. Expoziția analizează criza locuințelor cu care Londra se confruntă de când s-a transformat dintr-un oraș locuit de oameni într-o Mecca globală a investitorilor speculativi. Conform estimărilor actuale, aproape niciun locuitor al Londrei nu obține un câștig proporțional cu valoarea proprietății sale. Se speculează că o astfel de tendință va conduce, pe termen lung, la prăbușirea întregii structuri sociale a Londrei, pe măsură ce locuitorii săi de drept vor fi forțați să se mute și să facă loc agenților avuți ai „gentrificării” din lumea întreagă. Pavilionul încearcă astfel să analizeze problema într-un mod artistic, propunând spații 1:1 ale căror dimensiuni și dotări pot fi personalizate în funcție de timpul pe care locuitorii îl petrec în el: ore, zile, luni, ani. Pavilionul ce comentează astfel pe marginea felului în care producem spațiu, dar mai ales despre felul în care irosim spațiu, ne propune și o soluție: tot așa cum ne dezvoltăm propriile noastre vieți, cum evoluăm de la indivizi la cupluri și chiar la familii, tot așa ar trebui să evolueze și spațiul din jurul nostru. Pavilionul recent construit al Australiei este, probabil, cel mai surprinzător, oferind o bine-meritată pauză de la seriozitatea Bienalei, sub forma unei piscine în care vizitatorii își pot răcori picioarele. Ca în orice piscină, spațiul miroase bineînțeles a clor, există o terasă și chiar și un ziar ce poate fi lecturat pe marginea apei. Ce poate fi mai australian? Pe fundal, vocile unor naratori, înregistrați în prealabil, discută pe marginea disoluției acestui program public, cândva un veritabil locus al vieții comunitare. În pofida atitudinii sale relaxate, instalația reușește să își coordoneze vorbele cu faptele. Ea doar vorbește despre felul în care arhitectura publică de calitate facilitează interacțiunea între persoane aparținând unor categorii, origini etnice și grupe de vârstă diferite, dar îi și aduce pe aceștia efectiv laolaltă, fiind, probabil, unul dintre cele mai căutate locuri de la Giardini. Pavilionul Poloniei nu este un loc la fel de relaxat, alegând să dezvăluire la propriu eșafodajul ce stă în spatele spectacolului arhitectural. Solidarnosc!, par a striga polonezii, ce au ales să prezinte în manieră sindicalistă situația constructorilor ce făuresc capitalismul. Pavilionul ne reamintește că, în special în țările în curs de dezvoltare, așa cum este și a noastră, proiectele spectaculoase sunt construite, nu de puține ori, fără respectarea normelor de protecția muncii, de muncitori remunerați la negru, lipsiți de protecție socială sau contracte echitabile. Așa ajungem la proiectul Selfie Automaton. Proiect ce vorbește la rândul lui despre producătorii spațiului construit, cu observația că, de această dată, cei ce sunt puși literalmente sub lumina reflectoarelor, actorii spațiului, sunt arhitecții. Se pot spune multe despre expoziția pe care Tibi Bucșa și echipa sa, alcătuită din arhitecți, maeștri păpușari și artiști plastici, au montat-o în pavilionul național al României. Primul lucru care ne-a atras atenția a fost cât de impecabil funcționa ca piesă de final de traseu. După atâtea discursuri ceremonios didactice, pavilionul României oferea o abordare care, înainte de toate, era fascinantă. Explicația întregului concept este mai mult ascunsă pe unul din pereții holului principal de intrare, astfel încât intri fără a ști la ce să te aștepți. În momentul vizitei, am fost suficient de norocoși ca toate broșurile explicative să fie la rândul lor epuizate. Mai mult, pentru a rămâne întrucâtva fideli modului în care am ales să vizităm Bienala, am ales să citim cât mai puțin despre povestea pavilionului. Dincolo de imaginile ce au circulat pe rețele de socializare, singurele canale relevante de măsurare a notorietății, eu – și aici trebuie să mă credeți pe cuvânt – nu știam aproape nimic. Pentru început am fost furați de calitatea picturală a punerii în scenă. De cum intri, luminile scenografice pun întreaga atenție pe forța expresivă a marionetelor. Scena te imploră să o fotografiezi și, ca și în cazul machetei ADNBA, sunt convins că Selfie Automaton a fost printre cele mai imortalizate instalații ale Bienalei. Acest lucru în sine reprezintă un succes. Cadrul atent construit ascunde însă alte secrete, iar pentru a le desluși, cele trei instalații-mecanism ale pavilionului îl momesc pe vizitator să le pună în mișcare. De îndată ce amesteci în castronul cu mămăligă, marionetele încep să se miște: una își izbește constant capul de o farfurie, fără a putea să-și ridice privirea spre orizont; o alta se prosternează încontinuu la cele două fețe ale aceleiași monede, una înfățișând Casa Poporului, a doua Catedrala Mântuirii Neamului (numai românii vor înțelege aluzia), o alta interacționează cu un câine supus care așteaptă obedient resturile mesei, majoritatea însă te fixează pe tine, manipulatorul. Trăiți într-o țară semi-funcțională, guvernată prin comitete și comisii?... ați înțeles imediat despre ce este vorba aici. Instalația este o reprezentare miniaturală a sistemului, a felului în care sunt și vor fi lucrurile. Sistemul de marionete, de automatoni lipsiți de orizont funcționează, însă doar dacă alegem să îl punem în mișcare. Din acest motiv, viziunea propusă este oarecum pesimistă. Sistemul nu poate fi schimbat, el funcționează perfect și în mod automat, și chiar dacă alegem să stăm pe margine, să nu îl punem în mișcare, altcineva așteaptă la rând ca să o facă. Iar această observație nu este o metaforă. Ea s-a întâmplat chiar sub ochii noștri, în pavilion, cu toți vizitatorii lui. Ca piesă a acestui angrenaj de ițe și rotițe te poți chiar admira în oglinda atent plasată pe partea opusă. Acolo, această scenă aproape biblică se scrie ca un selfie. La stânga și la dreapta pavilionului, alte dispozitive explorează tema mai în amănunt. Masa comitetului, cu perspectiva sa răsturnată, poate părea o scenă desprinsă din Kafka numai cuiva care nu a compărut niciodată în fața unei astfel de comisii. Marionetele ce te privesc de la înălțimea mesei sunt, în ciuda trăsăturilor caricaturale, cât se poate de reale. Ele angajează temerile și emoțiile noastre cele mai profunde. În expoziția înrudită de la Galleria Nuova, din cadrul Institutului Cultural Român din Veneția, regăsim alte marionete automatizate, de această dată sub forma unui peștișor de aur sau a unei găini care face ouă de aur. În acest Imaginarium diferit, și totuși similar, nu sistemul, cât dorințele și tentațiile noastre cele mai adânci par a fi mecanizate. Și aici, ele ne așteaptă în semiîntuneric să le insuflăm viață iluzorie. Am părăsit Giardini având în minte marionetele automatizate, Galleria Nuova, gândindu-ne la menajeria ei de dorințe. Peștișorul de aur, ouăle de aur, masa comitetului. Acestea au fost imaginile ce ne-au condus pe drumul spre ieșire, amintindu-ne cumva că lumea noastră plină de dorințe și supervizori era acolo, undeva, așteptând să ne întoarcem... frontul nostru. |

| In 2014 an age was dying out as a new one was being born. At last this is what everyone thought when Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena was announced as curator of the 15th Venice Biennale. The man of the moment, the man of every activist architect, but equally of the establishment (for what else is the Pritzker if not such a recognition) was given the important task of organising the greatest show that the architectural field gives upon the world every two years. Aravena nomination signaled, especially in the more leftist circles of the field, a possible paradigm shift, hijacking the architectural discourse from the global flux towards more localised territories. The top-down, age of Rem was out, in was the bottom-up and political correctness. A bit too late one might say for not even Aravena is a committed leftist, as some might erroneously think. On the contrary, and one only has to listen carefully to how he builds his argument: “difficult complex issues require professional quality, not professional charity,” The moment for this biennale couldn’t be any better or worse for that matter, as we have to simply acknowledge the way in which the realities of our PC world are being overturned by the unexpected rise of populism and even fascism the world over, signalling the failure of multiculturalism and a return to old school Realpolitick. Mankind is certainly at a turning point. Architecture is not spared of this moment and one has to ponder if Aravena is not a populist agitator himself, riding a wave of general discontent with the profession as a whole. So, was his build-up of ideas and solutions going to be facing these new challenges, or was it to revisit the same themes and idioms that we have been seeing this past decade ad nauseam? Was it going to raise itself to the level of expectations surrounding it? Or was its more than ambitious theme going to be betrayed by the format itself? In this, the Biennale is most of the time if not frustrating then surely an exhausting experience. By walking, sometimes even running, rapidly ticking away, concepts, pavilions, experiences through a two-day show dispersed between two main sites and many other affiliated locations, the Biennale can amount to nothing but sensory overload.Moreover, what is one to make of the state of contemporary architecture by just visiting the Biennale grounds three months after its grand opening, as a tourist, without too much prior information on either the exhibitions or the debate around them? This was our lecture key. We chose it considering that now, more than ever, it was important for architects to deliver a clear and responsible message, less aesthetic and more ethic. And what did we make out of it?

To begin with Aravena’s main argument, the front is a condition of our world, a dialectical struggle around; quality of life, inequality, housing, sustainability, peripheries, traffic, informality, waste, natural disasters, crime, segregation, pollution, communities, and migration, that can be addressed only through a proper vantage point. (Enter the lady scrutinising the desert from the height of a ladder- the image of this year’s biennale). Each theme a front, each front in dire need of troops and resources. What type of troops? Good architects. At least this is what Aravena is trying to imply in a somewhat holier than thou statement, written in his argument. Only good architects be here. We must be lucky tourists, for this show is full of certitudes. Day 1, Arsenale We started our visit as most architects do at the Arsenale, considering that it is the place where the curated theme is best represented spatially. Here we somehow cheated, since we knew that through its layout the Arsenale has a more didactic approach, slowly building up the argument instead of presenting a random collection of rooms, as the Italian Pavilion in the Giardini does. We don’t know if Aravena intended it also to be so. Upon entering, the visitor is greeted with what seems to be a carefully conceived art installation, the redefines the overhead. There, above your head, a dense grid of vertical steel struts shrinks the space to the human scale, not without placing the entire weight of the room on the shoulders of the on looker. Aravena’s gesture emphasises the need to recycle, as the whole room is built with materials salvaged from the previous biennale. It feels however a bit staged, as all the carefully contorted lack any real dust or particles. Architects should know how a recycled profile looks like… Ethics 0–Aesthetics 1. The conceptual sketches depicting the build-up process of the biennale don’t help either. They speak more of an overwhelmed curator that in the end manages to capture himself in a selfie saying: LOOK! This is how we did the whole thing. But we are tourists, so we buy it, it’s visually cool and it speaks of our collective guilt of not doing enough about our waste. Let’s recycle! We are redeemed. Let’s move on. The first few rooms are a bit of a puzzle. They start with a very indicative installation by Al Borde discussing the price in time and money, but mostly personal energy imbedded in projects, considering their size, geographical locus, function, and social mission. It continues with Wang Shu’s didactic 1:1 display of recycled surfaces taken from his project for the Fuyang National Museum in China, and continues with the similarly sensual tactile and olfactory world of the Mongolian yurt, as reimagined by the research project of Rural Urban Framework and The University of Hong Kong, only to sink in the uninspired displays of the Russian practice Bernaskoni and the monumental and overtly pretentious displays of marte.marte architects. To be honest, the Bernaskoni dramatic model of a Matrioska building set within a pyramid structure literally expressing power is hacking the room to such an extent that no one is even looking at the other displays. Just ask any vistor with a photocamera. It is sadly not the only project that works in just such a way, Tadao Ando’s Punta della Dogana being another similar example. Fascinating as a model in itself, yet highly controversial as a project, it is saved only by the imbedded quality that any Ando gesture by now has attached to it from the start. Despite this, it is however nothing more but a show off of Tadao’s own front line with the city of Venice. The presentation of the project unfortunately slips into an idyllic and somewhat artificial stance. What is presented as a love affair is in nothing more than lip service, a picture album of a partially dysfunctional relationship, for the place is filled with guerrilla anti Ando messages. And for good reason, as one has to see the size of the concrete columns that he is to erect in front of Punta della Dogana. My first reaction was too look around for the petition against it. What ever happened to Charles Ray’s beautiful Boy with Frog? The show picks up again however when it tries to avoid these controversies and focuses on the architectural language that scarcity brings about. There, it is engaging and meaningful, either in its more poetic form as in Transsolar (Mathias Schuler) with Anja Thierfelder’s installation, emphasising the role of light in establishing immaterial quality, or as in the form finding studies done by the Philippe Block Research Group of ETH Zürich, highlighting the role of material and the benefits of computational aids in building with mud and clay bricks. These two spaces work in tandem and are perhaps the best part of the entire show, for they speak of what the architectural language can be, and should be, in a future built on finite resources. This theme is carried through in the next rooms in the similarly interesting if didactic pavilion by Anupama Kundoo Architects that discusses the plastic quality of modern prefab materials made however of natural biodegradable resources, and even later on in the informative installation of Hugon Kowalski and Marcin Szczelina, documenting the little known recycling industry that has sprung up in India. In between are a series of smaller scale projects that unfortunately get lost by choosing to speak their message either in overly long video presentations, (who really has time for those while running between places), or losing themselves in the language ambiguities of conceptual art. Neither of those, ADNBA’s Hilariopolis is unfortunately also a partial misfire, if only a minor one, in spite of its very important subject matter. ADNBA choses to speak of their town as a repository of childhood memories, past formative experiences and finally as their projects ultimate narrative resource. This city is presented as a fragment, a possible utopia that mashes up old and new. It is present in first person for the onlooker gazes upon it from the height of the apartment windows that serve as vantage points. As a well-crafted installation, the light drenched model, it is so pretty that it shifts the tone from the entire argumentation from the narrative content, concerning the general lack of quality in Romania’s newly established property market, to the byzantine embroidery of its container. It was none the less, judging by what we saw while studying it ourselves, one of the most photographed objects in the Arsenale. And of course there were several shows highlighting problems of a more urban or even territorial scale. Comparing the top–down projects of the welfare state with the anarcho-sindicalist, DIY procedures and tactics of the present BeL Sozietät für Architektur envisage a growth pattern in which migrant groups settled on German lands are assisted in building their own quarters with the help of standardised models and building manuals. Further on Grupo EPM highlight their work in Bogota, while Rahul Mehrotra and Felipe Vera present their scientific research of ephemeral urbanism, represented by the impromptu settlements popping up around the world for various reasons such as: migration, famine, economic change, festivals and catastrophes. The Arsenale’s general focus on cities is further augmented by the exhibition “Report from the Cities: conflicts of an Urban Age”, an exhibition that somewhat offers a measure of the challenges ahead of us: from overpopulation to uncontained growth, lack of physical space and resources to sustain this growth. Guess what parts of the world are growing fastest. Guess through what political systems these overpopulated mega cities are spatially, socially and culturally governed. The Arsenale continues with a combination of national pavilions and shows by well-established architects. Of the latter, one is faced with interpreting the baffling, one might even say severely mishandled selection of Kengo Kuma, Ensamble Studio and Peter Zumthor. They bring virtually nothing to the argument, and drag the whole thing into the ground, as Ensamble Studio clearly does by pouring concrete into the desert only to create ART. Only Shigeru Ban brings some sense to this selection with his subtle piece showcasing the natural life sprung across a real front: the Korean demilitarised zone. The Arsenale ends on a high note, outside, with four large scale mock-ups beginning with ORG Permanent Modernity, investigating the power of formal language in industrialised prefabricated concrete panels, NLÉ brilliant floating school that won the Silver Lion, SUMMARY’s equally interesting take on prefabrication proposing a low-cost concrete living module that can grow in metabolic fashion, and ending with Norman Foster’s spectacular low cost fan brick vault built together with ETH for the Future Africa EPFL project. After the somewhat vacuous formal aesthetics put on display by Zumthor and the rest, this exterior part serves as somewhat of a conclusion on what responsible architecture can accomplish through retained yet powerful formal gestures, through use of material and back to basics building techniques. Form follows not only function but needs and resources as well. To conclude, day one was a bit underwhelming, unconvincing. The whole arrangement of parts seemed somewhat unfocused. As a tourist, I could indeed selectively enhance my knowledge on different practices around the world, but only where it was didactically explained, and even then the whole thing took too much time to go through. In fact, even using the eight available hours, the whole thing was done in quite a rush and we even accidentally managed to completely miss out on an entire show: a world of fragile parts. In the end one comes out exhausted. Reaching the final exhibits like The Italian Pavilion you simply don’t care anymore, and all you want is to get yourself a spritz on some Venetian canal and look at the sea of people moving back and forth: world people. Unfortunately, there is still more to be learned about quality of life, inequality, housing, sustainability, peripheries, traffic, informality, waste, natural disasters, crime, segregation, pollution, communities, migration from the streets and piazzas of Venice than from any such show. Day and night, Venice has it all. Perhaps the second day would be better. Day 2, Giardini For the second day we wanted to conclude Aravena’s battle so it was only natural that we start our incursions into the Giardini through the Italian pavilion. If the Arsenale was, as expected, in most of its parts a didactic experience, highlighting techniques and processes, I for one felt that here, in the Italian Pavilion the emphasis was put on the architects themselves, each with his or her own saviour narrative. And some, if not most things were worth saving and worth the antics, don’t get me wrong, but somehow there were also things that felt like that they were saying more about their promoters, the architects, then about anything else. The Pavilion starts with the powerful two-story high image of Gabinete de Arquitectura lattice brick vault. It is first and foremost a testament of the power of architecture, of the space built to amaze us, using the simplest of materials, the most basic of shapes. The installation which won the Golden Lion for the best participation in the exhibition Reporting from the Front speaks poetically of things that we have lost to technics: craftsmanship, and a DIY mentality that allows us to take matters into our own hands and thus gain independence from developers and manufacturers. In this respect, it continues the argument set up by the Sir Norman Foster, Peter Rich and the ETH research team and focuses on readily available resources: clay and mud in this case, and how they can be turned not only into a cheap labour intensive building material, but into a newly rediscovered expressive force. No one of course imagines that the vault presented by Gabinete, empty as it is, has any other true purpose than presenting the beauty that still lays in such structures. No one expects, I think, to build such houses on a large scale. The project on display is none the less ambitious beyond its expressive gesture. It is the culmination of a practice that has flourished mainly for the people it has engaged with over time. And it is not the only project of the sort, as one may take note of the similarly expressive Studio Anna Heringer and Lehm Ton Erde Baukunst clay spaces, or of the expressive bamboo tectonics done by Simón Vélez or by Vo Trong Ngia Architects. On a similar front, but this time working on a more urban scale, we find the work of Christian Kerez and Hugo Mesquita addressing the issues of order and disorder in the Brazilian Favelas, and the reparatory gestures implemented by designworkshop : sa on a highly congested makeshift market organically sprung up in one of Johannesburg’s unfinished highway junctions. Both of these two projects work as top-down solutions for bottom up risen problems. The first studies the DNA of favelas trying to find patters and models that it can later replicate orderly, while the second remedies like an operating surgeon, stitching together clogged arteries and completing in this case unfinished spatial instances. Perhaps one of the few entries in this year’s Biennale that addresses the need to reconsider the existing architecture, French studio LAN’ focus their attention on retrofitting a series of collective housing units inherited from late modernity. Their exercise begins by looking intimately into the lives of their subjects, in a voyeur like exercise that tries to abandon the typical developer scheme in favour of a more tailored approach, emphasising specific personal needs. In a similar manner, Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano addressed this issue by rehashing some of their older metabolic housing schemes. However, by all means this should have been a more present theme in the Biennale, and one feels that not enough attention was given, at least in Aravena’s curatorial concept, to the fate of our already existing built context, to the way in which architecture has the potential to transform itself, according to our needs, either through upgrading or downgrading. Unfortunately, whenever the focus is shifted towards our own so called developed world, the issues relapse, most of the time, into presenting simple aesthetic living choices. The frugal, a temporary return to nature, to a world that is lost seem to define SANAA’s quests for inner peace, after the weight of all their globetrotting urban projects. They choose to shrug it off by operating with small gestures on a small and isolated island of the Japanese archipelago. In similar fashion Aires Mateus speak of their own battle in search of beauty, for what else can their fabulous dark room be? In many of its parts, the exhibition thus looks like a superhero team up, each superhero coming from a parallel world, city, context, some more real than others, fighting his own villains, using specific superpowers, some more spectacular than others. Some are present with typical top-down projects made late in their careers, displayed here mainly for their redeeming quality (David Chipperfield and Norman Foster’s work in Africa come to mind). Other projects are genuine statements of bottom-up, DIY, socially infused work ethic. There is no thin red line however between genuine heroics and outright posturing and the regular visitor is to a certain extent manipulated into white washing the whole group. This is entirely the literally whitewashed Evidence Room, thinking that everybody’s conscience is impeccably white. Set deep within this superhero layer, right in its core, one finds to his total astonishment a time bomb of sorts, coming from the past, still ticking. It confronts us with a different kind of white hero, an anti-hero armed with simple yet effective means of destruction. The whitewashed door with handles only on its exterior face, the leaning ladder carefully placed near the gazing window through which a guardian would check on the carnage, the double steel wire column used for the deployment of canisters, all banal in their form yet dreadful in their content. Contraptions devised from simple everyday objects, a door and a handle, a ladder, transformed as Hannah Arendt might say by the banality of evil. In their final improved design, the Zyklon B canister deployment shafts would ensure the rapid disposal of 2000 souls every single day. And what of the men? There is plenty of evidence in the room that these inanimate objects, these tools were carefully planned and designed by someone. First off the blueprints, all clearly drawn, all signed by architects. And then there is their picture. Standing next to their camp officers, in front of their achievement – the communal bath house – the architects seem accomplished. Their final reception pose. There is a deliberate difficulty assigned onto the onlooker in making it all out, in distinguishing the features of all these men. They come out only through a careful observation of the filigree relief of the white paper upon which a deliberate play of light and shade gives only a vague notion of what they looked like. In essence, they are all alike, architects, officers, camp bureaucrats, all share the same responsibility. Some might want to forget this past, or even contradict it all together as the self-proclaimed historian and holocaust denier David Irwin did. It was exactly against his high profile libel trial opened against American historian Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books that all this evidence was meticulously gathered, documented and recreated in 1 to 1 mock-ups by Professor Robert Jan van Pelt and his students at the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture. In the end, it turned out to be the most complex exercise of forensic architecture ever assembled. He has lost his case, but the deniers, those who wish to forget history, those who wish to “make things great again”, are still there, at large, and 2016 was in many ways their comeback. Some are definitely architects for we are no different when it comes to demographics. Lest we forget, for some, evil is banal, just the next commission. Outside We left the Italian Pavilion with a bitter taste of what the future might bring, but not without visiting its final piece of evidence, Manuel Herz and the National Union of Sahrawi Women’s refugee tent. As a neutral structure guarding the entrance to the Italian Pavilion it can be simply overlooked and we nearly did so. Inside it is poetically adorned with handmade tapestries made by the Sahrawi women themselves, speak of their plight. Here the women have sawn their own tragic story, for each tapestry is depicting a specific map of the displacement caused by the civil war ravaging Western Africa. In these circumstances, the artificially grounded tent, becomes a new long term home. IF you missed this tent you missed out on one of the best things in this Biennale. We almost this. And how cold we not, for in our eyes it really wasn’t there. We were not prepared to acknowledge its immaterial presence, its world in motion, set among the grounded monumental structures of the first world: a tent among pavilions, an artefact from the front next to abstract representations of imagined fronts. The first world though is not without its problems, and the national pavilions, with few exceptions chose to reveal them each in their own specific way. Most of the issues on display are however, in spite of their contextual particularities, universal in their scope. The issues of scarcity and its aesthetic qualities (Belgium), of systemic failure in the aftermath of an economic crisis (Spain, USA), the social and political problems concerning immigration (Germany, Austria), of housing and cost of living (England, France), the faith in technology and knowledge based solutions (Israel, USA), the role and position of the architect in the social structures that he is operating in (Hungary, Romania), the fate of buildings and their ever-changing psychosocial narratives (Australia, Nordic Countries), the reinterpretation of recent history and its built artefacts (Russia, Czech and Slovak Republics), all are clearly issues that to a certain extent could have been addressed by either of these countries. They never the less give a snapshot of the different battles each of these nations is currently engaged in. The Golden Lion for the best national participation was awarded to Spain’s “Unfinished” pavilion. Its curators chose to highlight the effects the prolonged economic crisis had on Spain’s building sector using mainly the language of photography. The main room uses only this medium, in an exercise that in many ways resembles in both form, content, and type of commentary, Petrut Calinescu and Ioana Hodoiu’s own Pride and Concrete project. The images on display depict abandoned infrastructure projects, empty parcels and mutilated landscapes, mainly unfinished houses that are still somehow inhabited in spite their lack of access to any basic infrastructure or utility. They are images that could have very easily be taken in any of the suburban growths that sprung out around most Romanian cities in the past two decades. In fact, by extensio-n, these projects are unwillingly related, for what is the main source of failure and abandonment in the case of Romanian developments if not the crisis in Spain, Italy or France. Thus, in many ways, the Spanish pavilion speaks not only of the Andalusian or Galician landscape, but of many other similar places from Maramures or Moldova, equally hit by the economic meltdown of the last decade. The second part of the Spanish exhibition offers a certain degree of optimism, in its methodical and thorough display of projects that managed to recalibrate their means and gestures in the wake of the crisis. This selection is by all means showcasing quality architecture that has managed to reconsider the problems of resources, participation, and DIY solutions. The Spaniards were thus able to further distil their already excellent school of restrained minimalism, turning scarcity into an expressive choice. It is a theme similarly addressed in the Belgian pavilion, this time through mock-ups that instead of focusing on actual projects, move the attention on the most trivial details and materials that an architect has at his or her disposal. However, if the Spanish pavilion speaks through its drawings diagrams and photos to the regular visitor or tourist, the Belgian one is more elliptical. The things on display are beyond banal to the untrained eye, bordering any aesthetic definition. It is perhaps a statement that most of the time our environment is not modelled by these aesthetic decisions, but by other economic circumstances or choices. Moving on the same street, the Dutch pavilion creates all sorts of unwilling subliminal connections to Manuel Herz refugee tent. It offers an almost make-believe vision of the Dutch blue helmets operating as pacifiers in several African nations. It is by all means a highly tailored optimistic vision, which in the light of previous notorious Dutch failures in Bosnia as well as more recent ones in stopping genocides, seems seriously misplaced. Did I mention that the whole pavilion is glamorously lit in a neon blue light? A similarly artistic installation is to be found in the form of Christian Kerez’s immersive space designed for the Swiss Pavilion. It is a structure that works well both in showcasing the latest research in form finding done by ETH, as well as in establishing a typical out of this world Swiss tone to the whole pavilion. Since Kerez already had the opportunity to tackle the main theme of the Biennale in the Italian Pavilion, here he shifted the attention on the emotion given by pure architectural form, a gesture that few of the curated shows have managed to do up to that point. The theme is somewhat followed in the Nordic Pavilion with a similarly poignant installation that for the first time offers the visitor access to the now iconic Svere Fehn concrete lamellar roof. The pavilion is inhabited by a large wooden pyramid that takes most of its space. On steps, following Maslow’s hierarchy, the visitors looking for a moment’s rest or simply looking at the ceiling, find several flyers depicting the most relevant project coming from the north. Next to them, at the base of the pyramid we find the therapy area. Here, while resting on the installed sofa beds, the visitor is presented with modern architecture psychological issues. Faithfull to their cultural models, the Northerners new nothing better but to take their latest built projects to the psychoanalyst. Further on, Denmark offers perhaps the ideal pavilion for any tourist since it is literally drowned in a sea of architectural models depicting the latest socially oriented buildings done in the country… and a video of Jan Gehl. The Russian pavilion is again opulent in its use of technology and ideology. It speaks of the need to reconsider the cultural heritage of social realism, trying to establish a creative link between that utopian cornucopian image favoured by Stalinism and the themes rehashed by what one might call Putinism. It is thus by far the most obvious state sponsored discourse put forth by any nation. Is it also anticipating the future of such shows? Compared to its expensive video walls and mock-ups, the German, British and French pavilions seem dwarfed in scope and resources. We cannot however address them without mentioning that the newly refurbished Japanese pavilion is again a typical, by the numbers, affair show-casing young practitioners operating in the area of small scale social housing. The exhibition feels however somewhat stale, since there is no real strong undercurrent to link all the projects. Literally one of the cheapest, the German pavilion has used the concept of scarcity and waste management to its fullest extent by offering an almost empty pavilion. Its narrative is presented through posters, diagrams and catch phrases that are operating solely on the surface of the walls. As expected, Germany has focused its attention on the issue of immigration, presenting a series of case studies that encompass cities, neighbourhoods, and families. It thus chooses not to speak of new architecture but of already existing contexts, of how these contexts are reshaped and modelled by their new inhabitants. It speaks of the conditions of both habitable space as well as of public, communal space. In similarly restrained manner, on the other side of the park the Austrian pavilion tackled the issue of immigration, by actually building the whole exhibition around a few immigrant families on which it spent most of its budget. Thus the exhibition is documenting through take away posters and newspapers the several different small scale interventions that have helped make the life of a few families of immigrants, squatting empty office buildings in and around Vienna, more worthwhile. Also addressing the problems of habitation, the UK pavilion uses a different approach. The exhibition considers the housing problems that London has been facing ever since it turned from a proper inhabited city into a magnet for global speculative investors. It is estimated that by now almost nobody in London really earns according to the value of their property. It is speculated that this will lead on the long term to a collapse of the entire social structure of London as its rightful inhabitants will be forced to move out in the face of wealthy global gentry. The pavilion tries to look at this problem in an artistic way by proposing full scale 1 to 1 spaces that can be tailored in size and amenities according to the time that their inhabitants spend in them: hours, days, months, years. It argues that just as we develop our own lives, as we grow from individuals to couples or even families, so does the space around us, and that perhaps we should be more careful to how flexible we therefore design especially our social housing projects. It thus tackles the issue regarding the production of space and with it of the spaces that we waste. Australia’s newly built pavilion is perhaps the most surprising, for if offers a much needed break, in the shape of a pool that the visitors can dip their feet in. The pool comes with a sundeck, chlorine scent, and a newspaper detailing the concept, that can be casually read by its side. Typically Australian! Several pre-recorded narrators are discussing how Australia’s pools are currently trying to regain their status as once powerful community centres. In spite of its typical Australian care free attitude, the installation manages to put its money where its mouth is. It not only narrates on how good public architecture enables the meeting of classes, ethnicities, age groups and so on, but actually acts as such an enabler, being perhaps one of the most sought after places in the Giardini. The Polish pavilion may not be such a leisurely place, choosing instead to show the scaffolding behind the spectacle of architecture. Solidarnosc! It seems to cry out, as the Poles decide to show the cost in labour that building capitalism requires. It works as a reminder, that especially in developing countries such as ours, our well designed spectacular projects are built often times without any regard towards building safely, fair and equitable pay for high risk jobs, or social protection for the builders. And then we reach the Selfie Automaton. It also speaks of the makers of architecture, only this time it is the architects themselves that are put in the spotlight. A lot can be said about the exhibition that Tiberiu Bucșa and his team of designers, puppeteers and artists has put forth in the Romanian National Pavilion. The first thing that struck us, was how well it works as an end piece, for the whole Biennale. After all the ceremony and didactic utopianism of the previous pavilions, the Romanian pavilion offers an approach that is first and foremost mesmerising. The explanation of the whole concept is somewhat hidden behind the main entrance hall, so one enters without knowing much what to expect. We were also lucky that by the time that we visited the Biennale the flyers explaining the concept also ran out. Moreover, to remain faithful to our mode of visiting the Biennale, we chose to read as little as possible about it. Aside from the images that were circulated on social networks - the only relevant chanels for measuring notoriety - I for one knew almost nothing, and you’ll have to trust me on that. For starters, one has to notice how picture friendly the whole thing is. As soon as you enter, the stage-like lighting and expressive automatons beg you to take their pictures. It surely must have been one of the most photographed installations of this year’s Biennale. In this alone it is a success. However, there are deeper secrets hidden behind the picture perfect settings, and the three setups entice the onlooker to engage with them in order to gain access to their true meaning. As you turn the spoon in the polenta cauldron, the automatons start moving: one constantly bashes his head against a plate unable to rise his eyesight toward the horizon, another continuously prostrates to two sides of the same coin, depicting either the People’s House or the People’s Redemption cathedral in Bucharest (only Romanians will understand), another one engages with an obedient dog waiting for scrubs at the side of the table, but most of them point at you, the manipulator. If you live in a partially functional country such as ours you immediately understand this is a miniature symbolic re-enactment of the much revered SISTEM, or of the way things are. However, the system that we so despise only works if we choose to let it work, to put it in motion, the exhibition seems to tell us. Therefore, the vision put forth is somewhat bleak. The system cannot be changed, it’s automated to perfection, and even if you choose not to turn it someone else is waiting in line to do it. This is no metaphor, as you can literally see it unfolding right in front of your eyes. And as you do this, you are even allowed to see yourself in the mirror carefully placed on the opposite side, in which this whole almost biblical scene unfolds, with you in its entrapments. To the left and right other devices explore this theme further. The committee table, with its overturned perspective seems like a scene from Kafka, only to someone who has not been before in such a commission. The automata here are as real as they can get, for they ultimately work with our deepest fears and emotions. In its sister exhibition at the Galleria Nuova at the Romanian Cultural Institute in Venice, different kind of automata take shape in the form of a gold fish or a hen laying eggs. In this different yet similarly darkened Imaginarium, it is not the system but our deepest desires and temptations that seem mechanical. Again, they wait for our intervention. We left the Giardini with the automata in mind – Venice just as we existed the Galeria Nuova with its fleeting desires. These grotesque images were our last companions, showing us on our way out, and somehow telling us that our world of wishful thinking and overseers was out there waiting for our return. There was our front. |

foto: Ovidiu MICȘA

Tadao Ando, Punta della Dogana Museum in Venice

Rural Urban Framework, The University of Hong Kong, Joshua Bolchover, John Lin, Settling the Nomads

Wang Shu’s and Lu Wenyu’s Amateur architecture studio, Fuyang National Museum, Hangzhou

Block Research Group at ETH Zurich and Ochsendorf, DeJong & Block with The Escobedo Group/ Beyond Bending

Block Research Group at ETH Zurich and Ochsendorf, DeJong & Block with The Escobedo Group/ Beyond Bending

Transsolar + Anja Thierfelder, Lightscapes

ADNBA, Hilariopolis

ADNBA, Hilariopolis

BeL Sozietät für Architektur, NEUBAU

Marcin Szczelina and Hugon Kowalski, Let’s talk about Garbage

NLÉ, Floating School

ORG Permanent Modernity, Platonic Panels

Gabinete de Arquitectura, Breaking the Siege

Norman Foster Foundation, Future Africa EPFL, Ochsendorf, DeJong & Block Research Group, ETH Zürich, Droneport Prototype

Anne Bordeleau, Sascha Hastings, Donald McKay, Robert Jan van Pelt, Evidence Room

Anne Bordeleau, Sascha Hastings, Donald McKay, Robert Jan van Pelt, Evidence Room

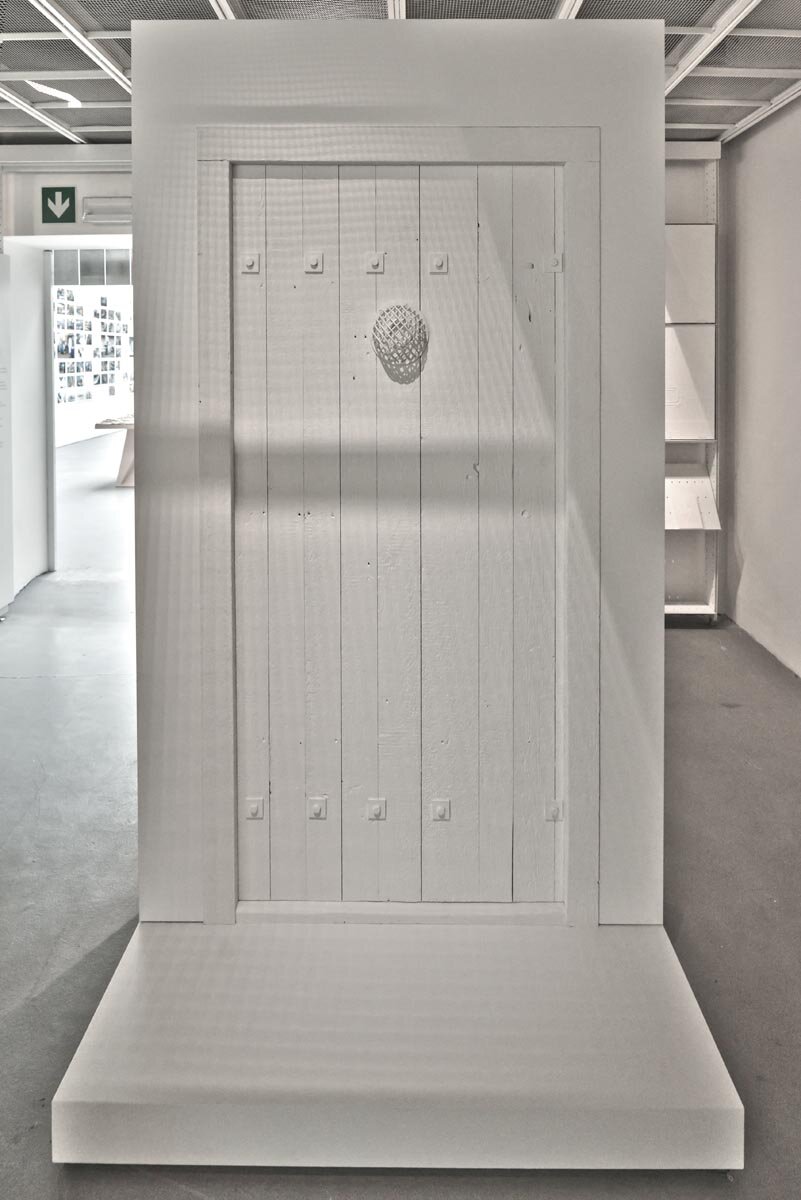

Anne Bordeleau, Sascha Hastings, Donald McKay, Robert Jan van Pelt, Evidence Room

Anne Bordeleau, Sascha Hastings, Donald McKay, Robert Jan van Pelt, Evidence Room

Iñaqui Carnicero & Carlos Quintáns, Spanish Pavilion, Unfinished

Iñaqui Carnicero & Carlos Quintáns, Spanish Pavilion, Unfinished

Architecten de Vylder Vinck Taillieu - Doorzon InterieurArchitecten - Filip Dujardin, Belgian Pavillion, Bravoure,

Manuel Herz with the National Union of Sahrawi Women and Iwan Baan, Pavilion of the Western Sahara

Malkit Shoshan, Dutch Pavilion, BLUE: architecture of UN peacekeeping Missions

Christian Kerez, Sandra Oehy, Swiss Pavilion: Incidental Space

Aileen Sage Architects, Michelle Tabet, Australian Pavilion: The Pool – Architecture, Culture and Identity in Australia

Jack Self, Shumi Bose, Finn Williams - British Pavilion: Home Economics

David Basulto, James Taylor-Foster . The Nordic Pavilion, In Therapy

Petr Hájek, Ján Studený, Marián Zervan, Monika Mitášová - Czech and Slovak Pavilion: The Care for Architecture

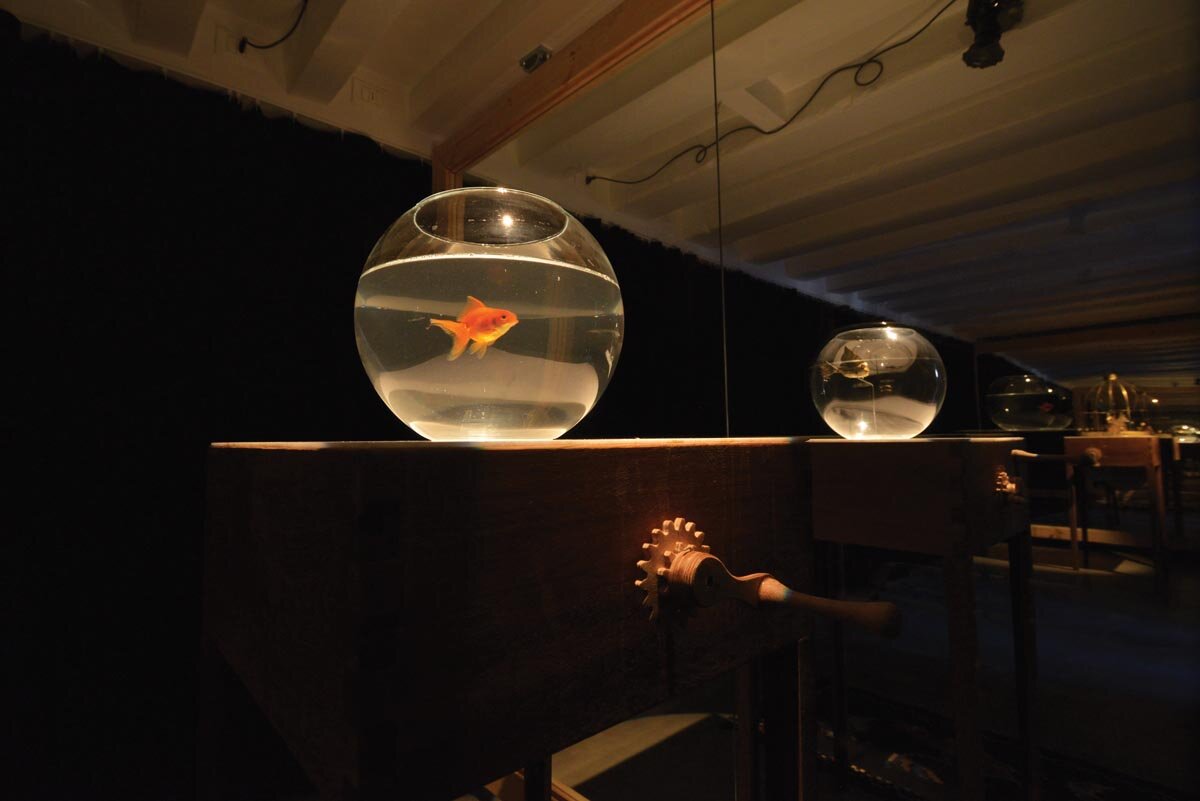

Tiberiu Bucșa, Gál Orsolya, Stathis Markopoulos, Adrian Aramă - Romanian Pavilion: Selfie Automaton,

Tiberiu Bucșa, Gál Orsolya, Stathis Markopoulos, Adrian Aramă, Romanian Pavilion: Selfie Automaton

Tiberiu Bucșa, Gál Orsolya, Stathis Markopoulos, Adrian Aramă, Romanian Pavilion: Selfie Automaton

Tiberiu Bucșa, Gál Orsolya, Stathis Markopoulos, Adrian Aramă, Romanian Pavilion: Selfie Automaton