Eye space vs Foot space

We are talking about the space of the city1; about the modern antagonism between the old city and the new city or about the postmodern or contemporary coexistence of these juxtapositions, a coexistence that is not, however, without its problems. In any city with a bit of history, and therefore in almost all European cities, we can observe the leap in scale that has taken place over the last hundred years which, due to the amount of built environment produced, has brought us to the point where we are now at the point where it is difficult to distinguish between a historic fabric and a modern or contemporary one.

This reveals a succession or an intermingling of the two, depending on the way in which the city has developed - linear or in leaps.

The low quality of contemporary and modern spaces is commonly discussed in contrast to the high quality of traditional fabric spaces. In Bucharest, which has undergone very violent transformations in leaps and bounds, this separation between old and new, which in most western European cities is highlighted by the center-periphery relationship, is less evident. This is transformed without too many questions into the good-good ratio when discussing the quality of city spaces. In 2005, I was confronted with the problem of building new on the boundary between the old city walls and the modern and contemporary expansion.

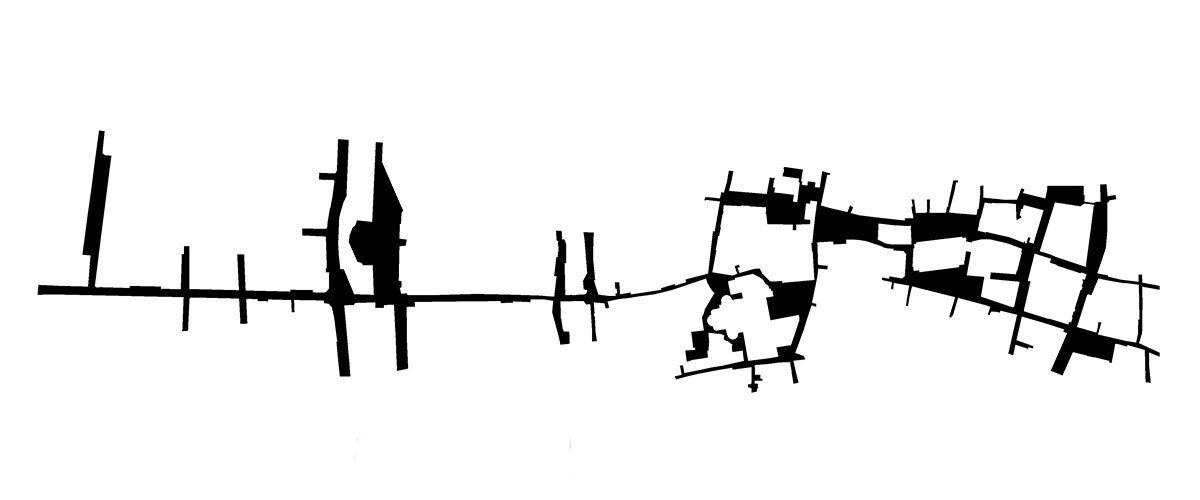

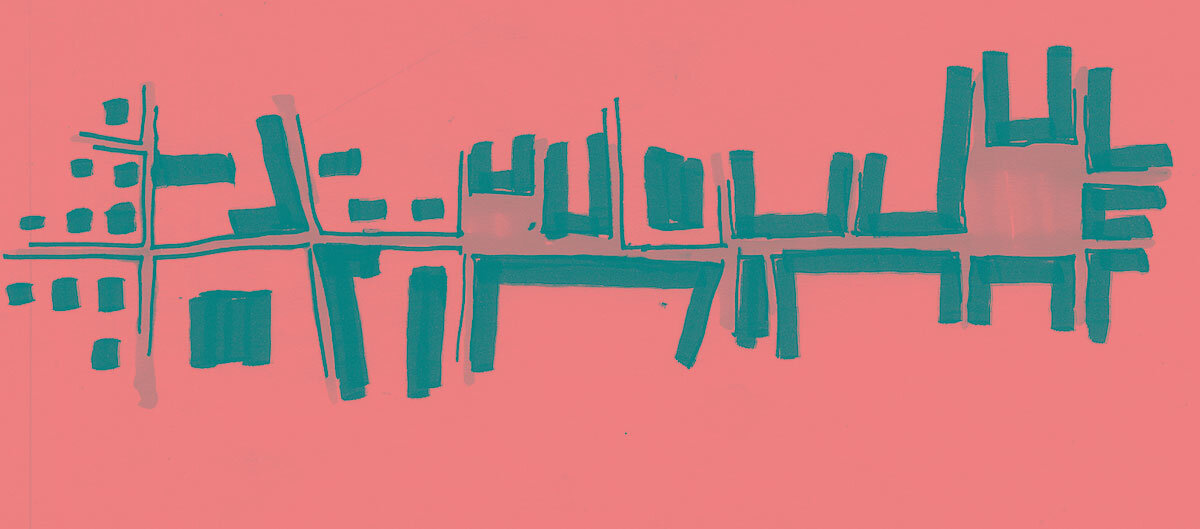

It was a diploma project, the city being Padua. It is a very clear city in terms of spatial separation of different historical periods. One can see in Fig. 1 both the separation between the old city and the periphery, but also within the old city the separation between the Medieval and the Renaissance period, when we witness a first jump of scale2.

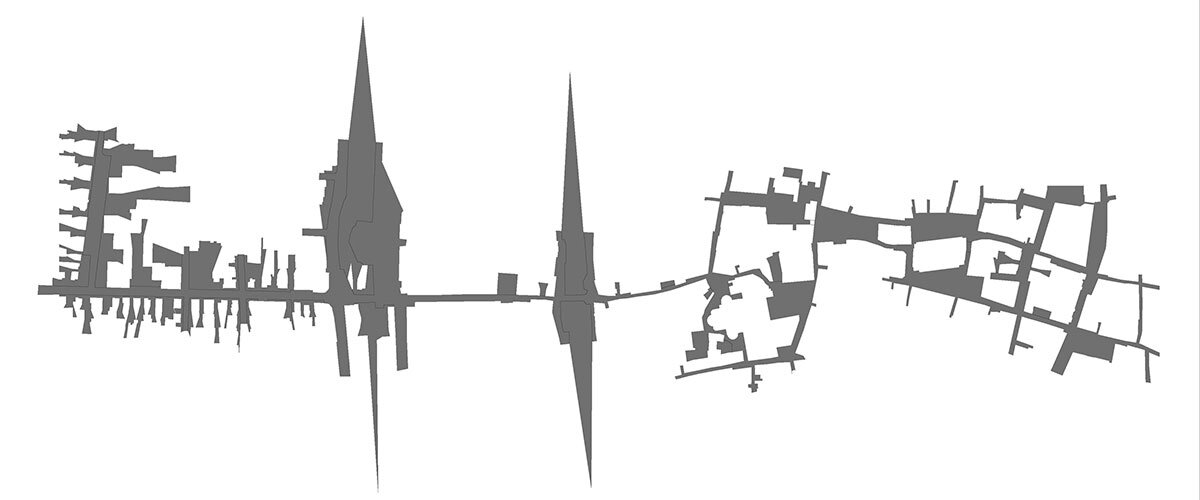

In an attempt to find a clue as to how the building required by the theme was to be designed and, implicitly, to redefine the urban space through this intervention, I took the pedestrian space as a reference point, because it was to this space that I had to refer in that case, as it is also the one to which we usually refer in the discourse on the quality of urban space. I sketched a cross-section through the city from the center (the old and compact city) to the periphery (the new and diffuse city3). We can see the compact morphology of the buildings in the historic center and the freestanding contemporary objects in the periphery (Fig. 2). This is something we have all noticed, and it is not enough to fuel an analysis that attempts to quantify the quality of space by quantitative criteria. As in any analysis, we are looking for a minimum of two key elements with values by which, by comparing them to some established normal values, we can establish a diagnosis. Because we did not know what normal values we were looking for, we started from the premise that the normal value, in fact the one we wanted, is the one found in the historic city.

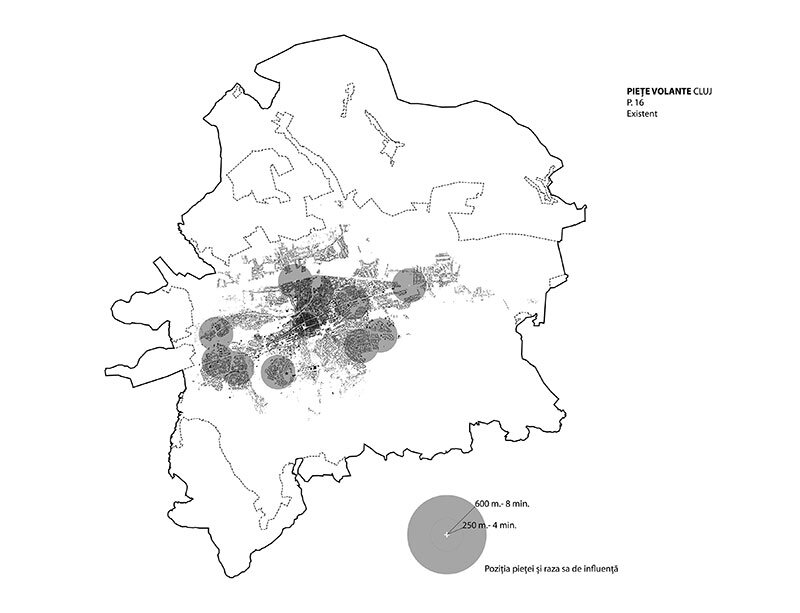

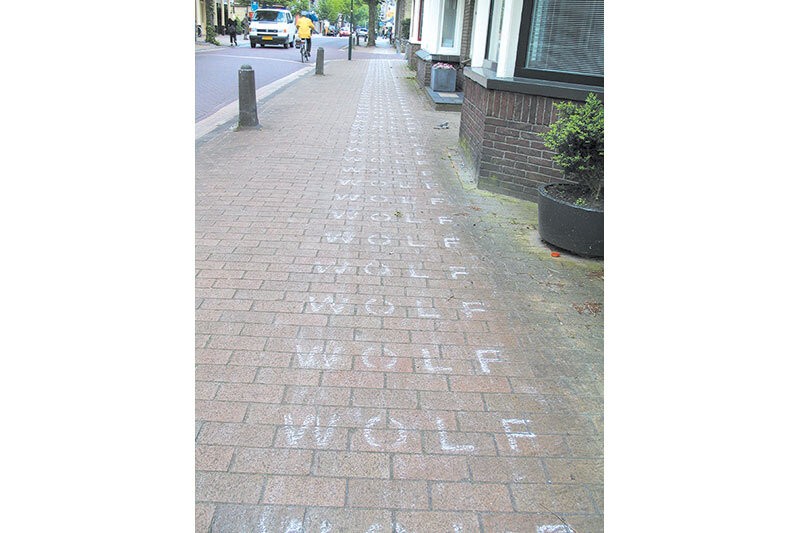

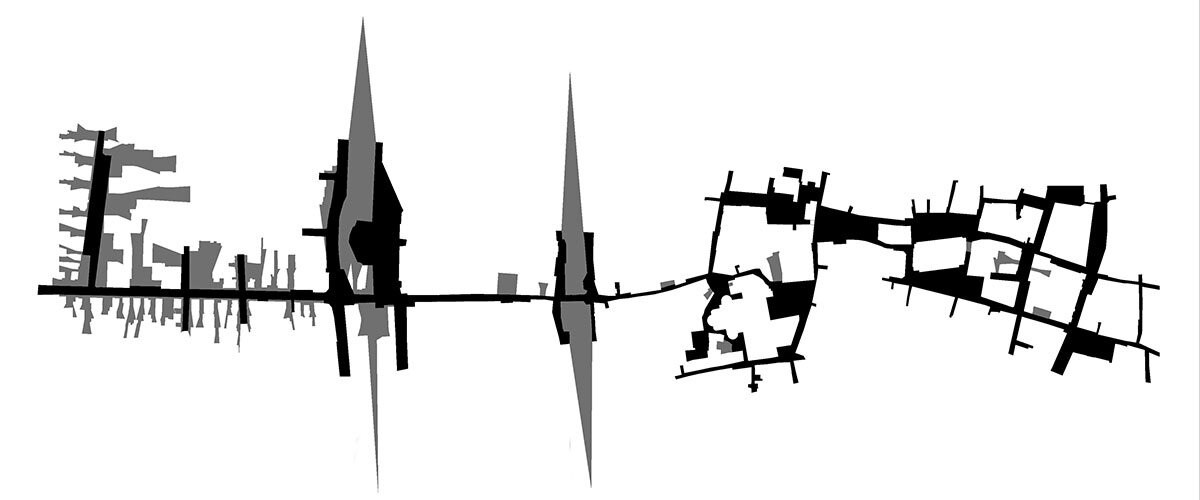

But establishing what would give us the values to compare was more difficult. Two contemporary architects - Luigi Snozzi and Michel W. Kagan - came to my aid. Luigi Snozzi, in an aphorism, says that architecture must be made with feet, that is to say that the space we want to define by architecture is measured by steps, it is always about human size and proportion. The other observation, made by Professor Michel W. Kagan on a project I was working on, criticized the too direct way in which space is revealed, this leaving too little room for the imagination - how much we can or should see directly and how much we can or should only intuit from a given space. The fact that the two architects are, to my mind, radical modernists only adds further power to the observations made. I have chosen two elements to help this deciphering: one - the space of the foot, the second - the space of the eye. The first - foot space - is what you can actually walk through as a pedestrian, and the second - eye space - is what you can see, how far, or more precisely, what defines the limits of your vision in the space you walk through. Taking the values of these two observations separately, we can observe the following: For the space of the foot we observe that, in the traditional semi-piéonized city, the street can be traversed from one end to the other in width, which makes that, although in absolute dimensions its width is smaller than that of streets with important car traffic, spatially they are perceived larger, due to our possibilities to traverse them completely. In the same vein, the city squares and arcades help to emphasize the fact that, in the historic center, the space through which we can walk is quantitatively clearly superior to the contemporary extension (Fig. 3).

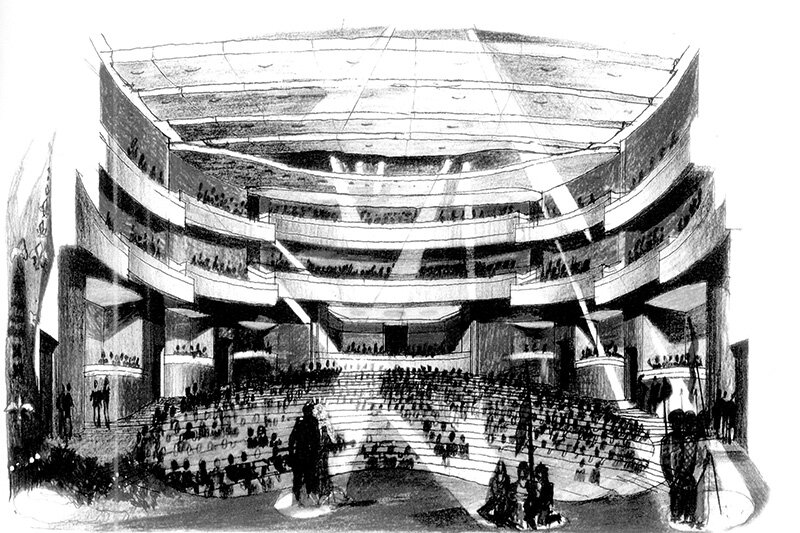

For the space of the eye, we note that in the traditional city, it is well defined by the continuous building, while in the periphery, the eye is lost among the houses, and it is unclear in which plane what we see ends (Fig. 4).

Put together, these observations and their values yield a surprising result (Fig. 5). In the old town, the space of the eye and the space of the foot largely coincide.

Read the full text in issue 6/2012 of Arhitectura.

NOTES:

1 In this text we discuss urban space with reference to public space but without the connotations that the word public implies. We will talk about the physical space in which people can move, which we will interpret as some kind of relief, a piece of territory, but which is a second nature - a built, artificial one.

2. Padua is a special case of study, being in the territory where Palladio carried out his extraordinary work in which he invented the program of the urban villa in the countryside - an expression of the mutations in Venetian society. On another note, Padua is home to the largest urban square - Prato della Valle, and the city is second only to Bologna in terms of the total length of its porticoes - another quality element in the urban space that we find in the common places of the quality of the built space.