For a reconsideration of modernist methods of monument conservation as part of the architectural heritage of Hungary

Thematic Dossier

FOR A RECONSIDERATIONMODERNIST METHODS OF MONUMENT CONSERVATION AS PART OF THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE OF HUNGARY

text and photo: Arnóth Ádám

When we talk about 20th century architecture, we usually refer to the new buildings of the period. However, we should not neglect the fact that the restoration and conservation of historic buildings can also be a valuable testimony to the history of architecture, a segment of heritage that is also part of 20th century architecture and worthy of preservation.

These restorations have complied with the provisions of the Venice Charter, based on a historical-analytical approach and, at the same time, modern ideas in art and architecture. Such interventions should not be "corrected" just because our generation does not agree with them, but analyzed and evaluated in a similar way to the other layers of the history of the building, in order to preserve the authenticity of monuments in all historical stages.

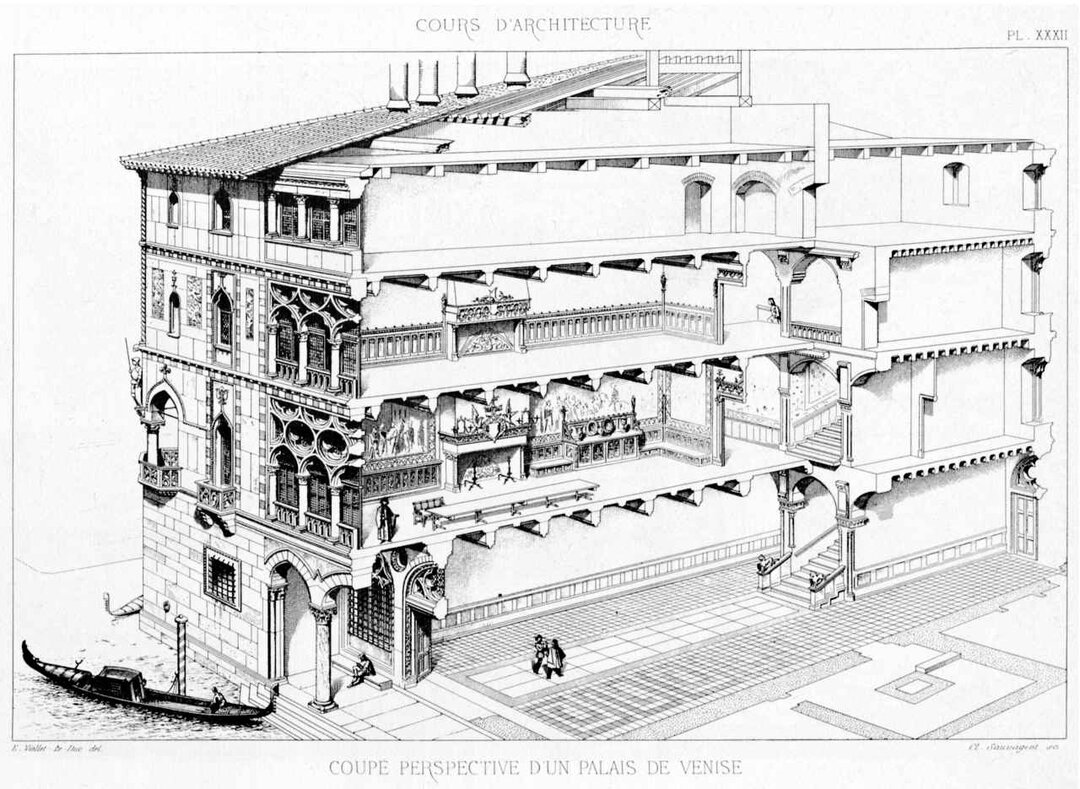

Historicist examples and prototypes of the modern thinking paradigm

Restoration concepts in Hungary in the second half of the 19th century are predominantly Romantic and historicist (as in Europe as a whole). Restorations are mainly impressive and highly ingenious, but they are not authentic for the most part because they represent hypothetical hypostases of the building in ideal conditions of realization and preservation.

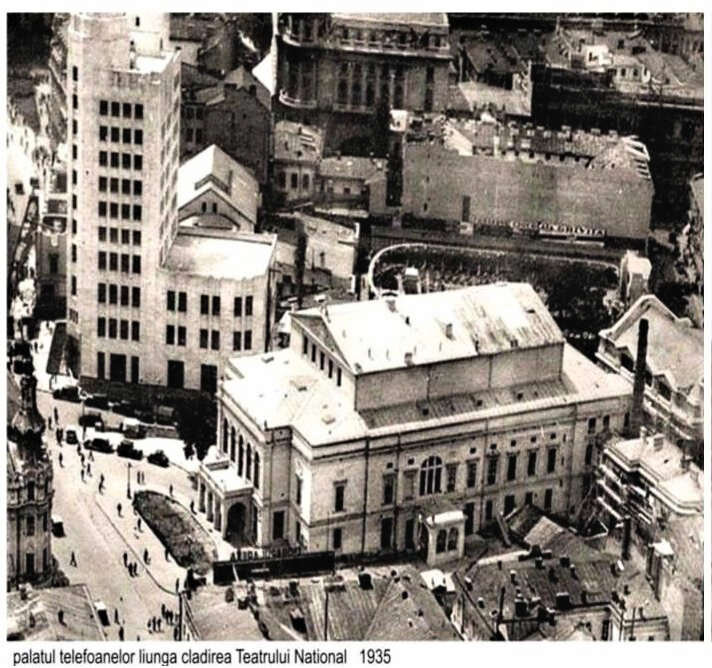

Before the restoration in the late 19th century, the buildings housing Matthias Church and Fishermen's Bastion (Budapest) were much simpler. They have become important landmarks of the urban landscape, but the monuments are not considered authentic in contemporary terms. Recent interventions on the building have restored the church to its 19th-century, not medieval, appearance. An 18th-century painting of Pécs Cathedral illustrates all its historical periods, from Romanesque to Baroque. Following restoration at the end of the 19th century, the church fulfills the conditions of a pure Romanesque style.

In the first half of the 20th century, a number of restoration works were carried out that can be considered authentic in today's terms. The earliest is the monastery church in Zsámbék, which survived in a state of ruin even after restoration more than 100 years ago. The new additions and unidentified or structurally motivated formal details are clearly distinguishable from the old original parts because the original stone was replaced by brick.

The remains of the chapel of the royal palace in Esztergom were uncovered by archaeological excavations. The anastylosis of the chapel was carried out using the excavated elements and according to scientific criteria. In this case, too, exposed brick was used for the reconstructed segments of the building during restoration in 1938. The exterior illustrates a delicate Italianate style - the Novecento, one of the specific architectural styles of the time.

A similar architectural language was applied to the Székesfehérvár basilica to frame the perimeter of the garden, which houses the ruins of one of the most important churches in medieval Hungary. The new arcaded buildings imitate medieval monastic buildings, with Italian Romanesque architecture having a major impact on the original church.

In the mid-16th century, the Turks built a mosque in the central square of Pécs; the building was converted in the 18th century and served as a metropolitan parish church for almost 300 years. Intervention in the 1940s restored the mosque, preserving the original Ottoman architecture, except for the extension of the rear façade, which was designed in a different contemporary architectural language, inside and out.

Modernist examples

After these early examples, a large number of restoration works were carried out in the spirit of modernist thinking by the National Inspectorate for the Protection of Historic Monuments (OMF), established in 1957. It has worked for 30 years and has enjoyed an international reputation. On the one hand, the restoration work has strictly adhered to the objectives of the Venice Charter, applying a historical-analytical approach; on the other hand, it has conformed to modern concepts in art and architecture. The coexistence of different periods is natural in the case of a historic building, but the existence of the temporal dimension in art is an idea of the 20th century, especially in the case of a heterogeneous composition made of a series of fragments, a collage resulting from the conflict of different elements.

This type of restoration uses elaborate methods, particularly in terms of identifying missing elements such as vaults, openings or even the original spatial configuration or size. It may be a type of abstraction - again, a notion specific to modern art. The new extensions use contemporary structures and materials in a creative way: they are in sympathy with the old building, generally deliberately isolated from the original entity.

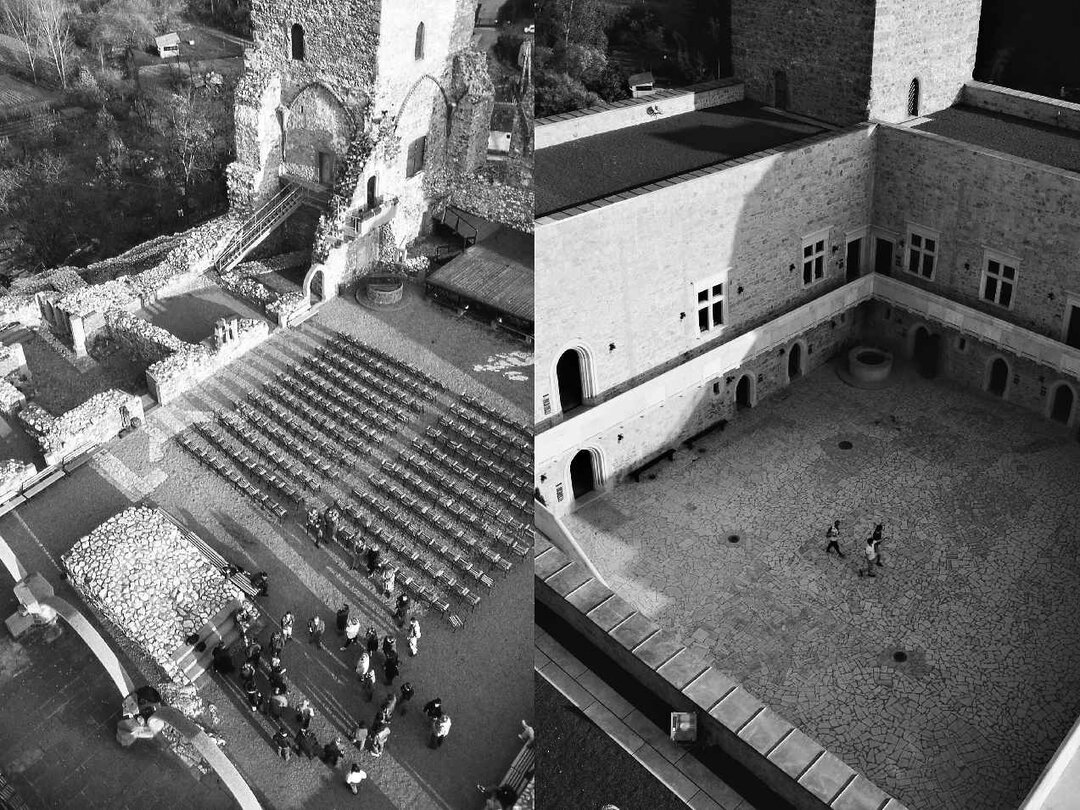

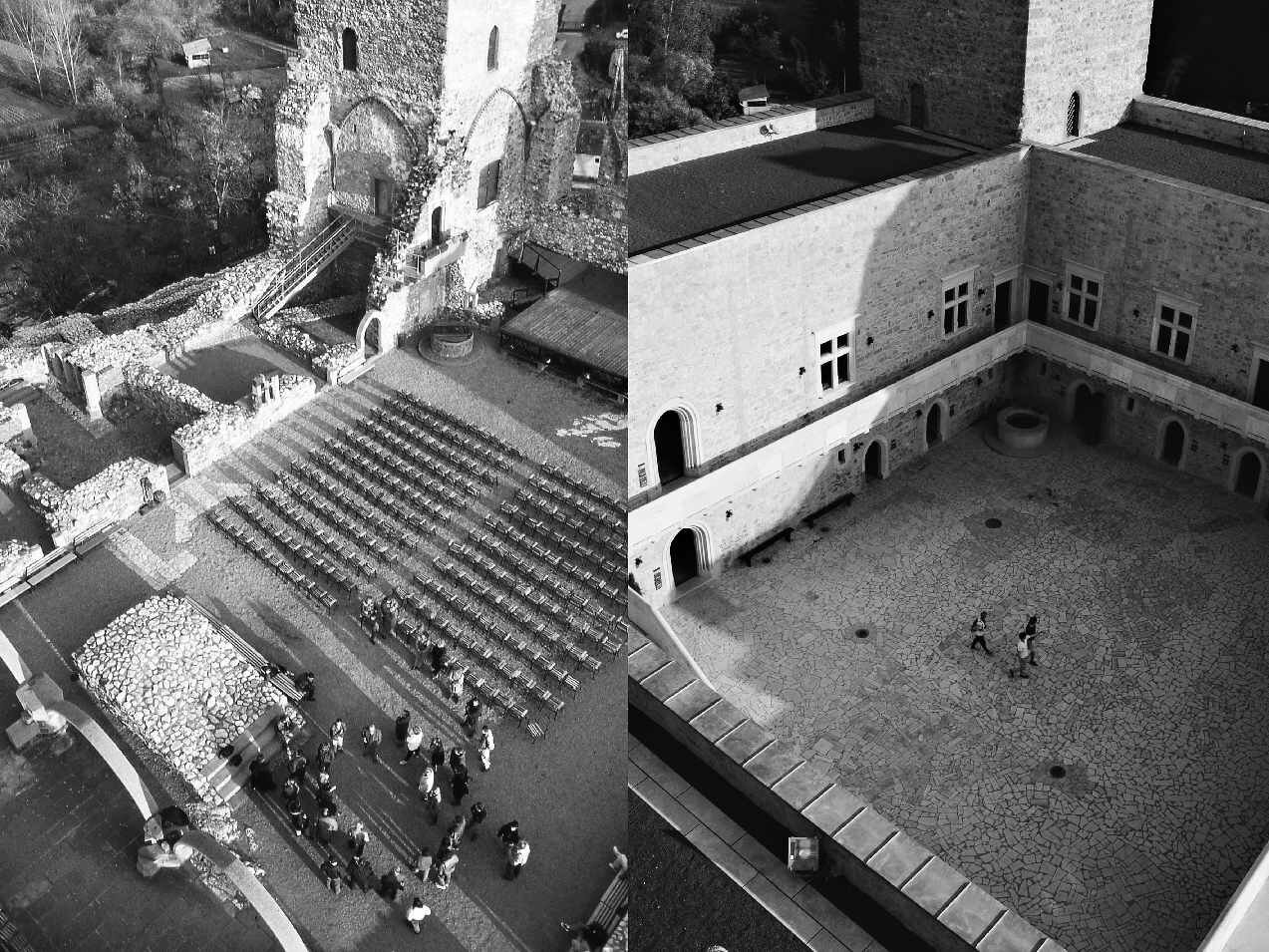

The Romanesque Benedictine monastery of Vértesszentkereszt, built in the middle of the forest, was abandoned after the Middle Ages. Even so, a series of new extensions helped to restore the original structure and space: the columns and arches of the vaults were reinforced with reinforced concrete elements. The resulting structure indicates the height and vault of the collapsed nave and supports the copies of the bas-reliefs in their original position. This detail of the restoration, which contradicts the logic of the ruin, also represents a characteristic 20th century solution in terms of materials, structure and aesthetics.

The donjon of Visegrád (Salamon Tower), built in the middle of the 13th century, is the oldest fragment of the royal fortress complex. The ruins have been partially restored in a historicizing style. As the building deteriorated, a modernist restoration was necessary in the early 1960s. The collapsed part of the building was rebuilt and reinforced concrete was used for the facades, the result being considerably different from the original design, especially in terms of the rusticated appearance and the narrow horizontal windows. The intervention was never a great success, but it is a characteristic solution that bears a strong period stamp. The destroyed vault at the top of the tower has been replaced by a metal structure which reveals the original shape of the spaces and keeps the surface of the walls intact.

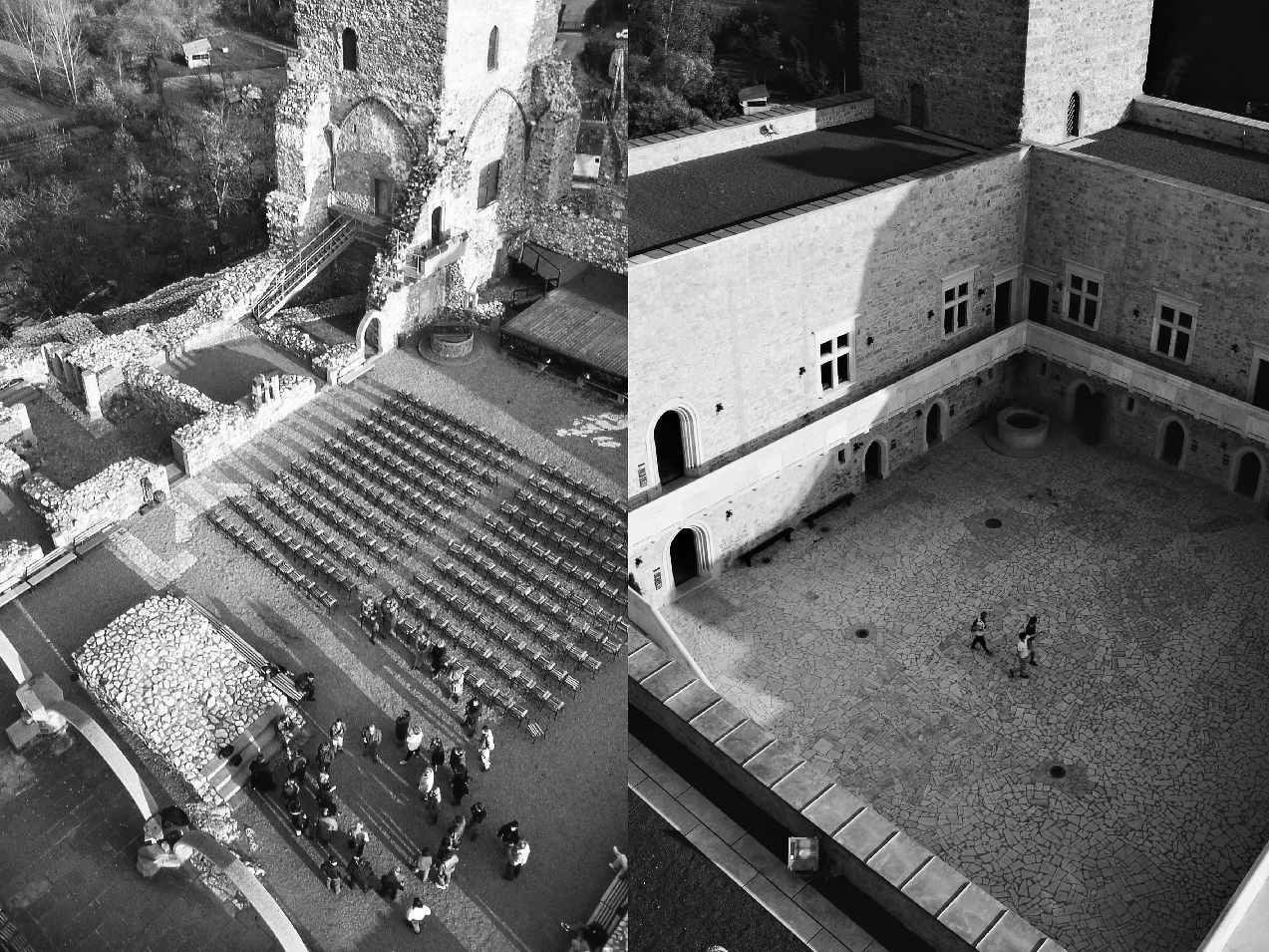

The restoration work carried out in the 16th century makes the Simontornya Castle (13th-14th centuries) a remarkable building. The new brick structure reveals the original volume of the building, supporting a fragment of the stone parapet in its original position. The castle was surrounded by a courtyard with Renaissance-style arches of which only a few traces remain; only two arches have been reconstructed using a few original fragments, making it possible to display the early and late remains of the façade. This structure and the simple design of the new interventions compose an interesting new image of the castle. (Fig. 1)

Like most of our medieval churches, the church of Nagyszekeres was transformed by Protestants in the 16th century. The original shape of the roof, the medieval plaster type and the restoration of the windows were realized during the conservation work. The ribs and the other segments of the collapsed Gothic vault were found during the research. With the help of the fragments found, it would have been possible to reconstruct the entire vault of the altar. However, a single fragment of the rib network was reconstructed as an anastylosis which preserved the painted ceiling dating from the 18th century. The solution is based on a modern assembly of the original parts, eliminating the need for new additions. In this way, different historical periods are presented successively, helping visitors to understand the turbulent history of the church, the congregation and ultimately the village. (Fig. 2)

The Turkish Mosque of Siklós, realized in the mid-16th century, was known only from an old sketch. Its transformed and deformed ruins stood in damaged outbuildings and were identified as part of the mosque in the famous drawing. Reconstruction of the volume of the building was carried out following research and brickwork and a pyramidal roof were used. The original vaulting is indicated by an ingenious wooden structure, as is the destroyed stalactite vault. The so-called dome has been suggested by a welded frame-structure. This interesting solution makes use of contemporary structures and materials that are different from the original, but still manage to suggest the building's vanished space.

The so-called Fire Tower of Sopron is a representative example of the restoration works of the 1970s, but also a relatively recently realized new model of intervention. The tower stands on the same spot where the entrance to the city center has stood for two thousand years, from Roman times to the present day. A small neighboring building was demolished at the end of the 19th century. The 40-year-old structure that replaced the missing building had to fulfill three tasks: to reinforce the tower, to ensure visitor access to the tower, and to cover and display the Roman and medieval remains on the site. The solution was a modern square reinforced concrete structure with a pitched roof and characteristic openings. The interior benefits from a remarkable space with rough surfaces whose pronounced architectural effect is still visible today. The other side of the building covers Roman and medieval ruins. Recently, a new visitor center was built in the perimeter. It has to some extent managed to restore the appearance of the 1970s building. The footbridge has been modified but the suspended structure remains unchanged. The ceiling is supported by high concrete walls, and the new visitor center, designed in modern colors, is inserted into this space. Although the presence of these transformations is strong, the original concept of the interior can still be perceived.

Whatever the era, the architecture of previous periods is always vulnerable. This is clearly demonstrated in the case of conservation. At present, a large proportion of new restorations do not like to emphasize the importance of history; the main aim is to make the restoration as easily understandable as possible to the public; therefore, they do not shy away from using copies, as in the past. Visitors, decision-makers and even some specialists are unanimous in their rejection of modernist architecture. There have already been many losses.

Remains of the Egyptian cult and the Roman sanctuary of the goddess Isis were discovered during archaeological research in Savaria, now Szombathely. The carved fragments were placed in their original position using an abstract reinforced concrete construction. The solution became a cited and worthy example at the 1964 Venice Charter conference. A few years ago, the supposed existence of the original building was questioned. A new version was drawn up according to which the building had six columns instead of four. Also, the original stone fragments had to be removed due to advanced decay. Subsequently, the old structure was demolished. The solution was a conceptual reproduction of the original building. The reconstruction uses copies of the original fragments, inserting them in the same positions as they were in the 1960s. Although the form has a higher degree of authenticity than the previous one and is easier for the public to understand, the time dimension cannot be perceived, making the replica completely lifeless. The new temple looks more like an exhibit rather than reflecting the original ingenious architectural concept (Fig. 3).

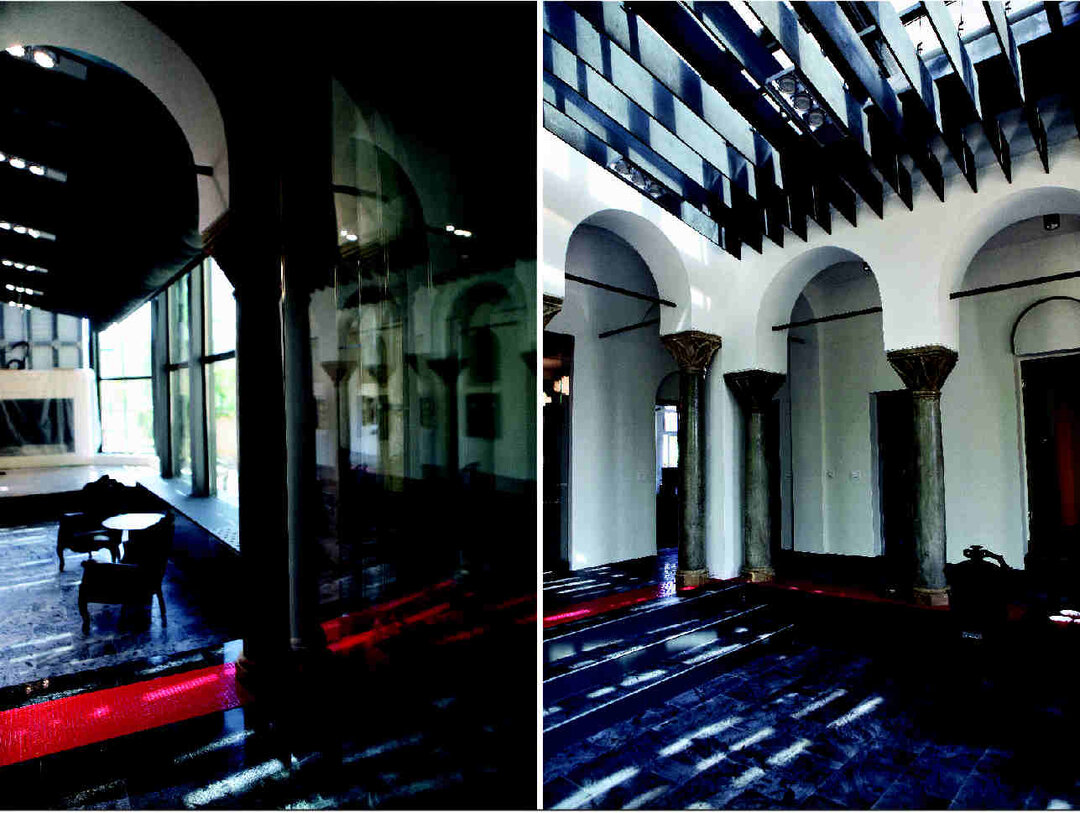

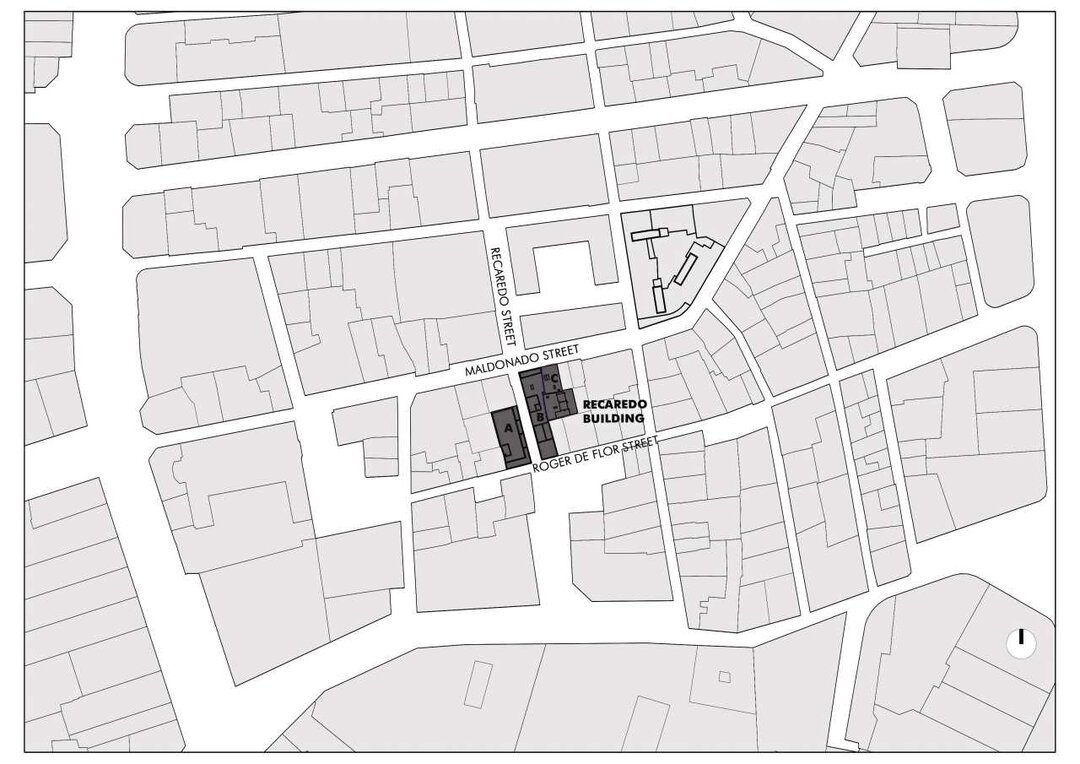

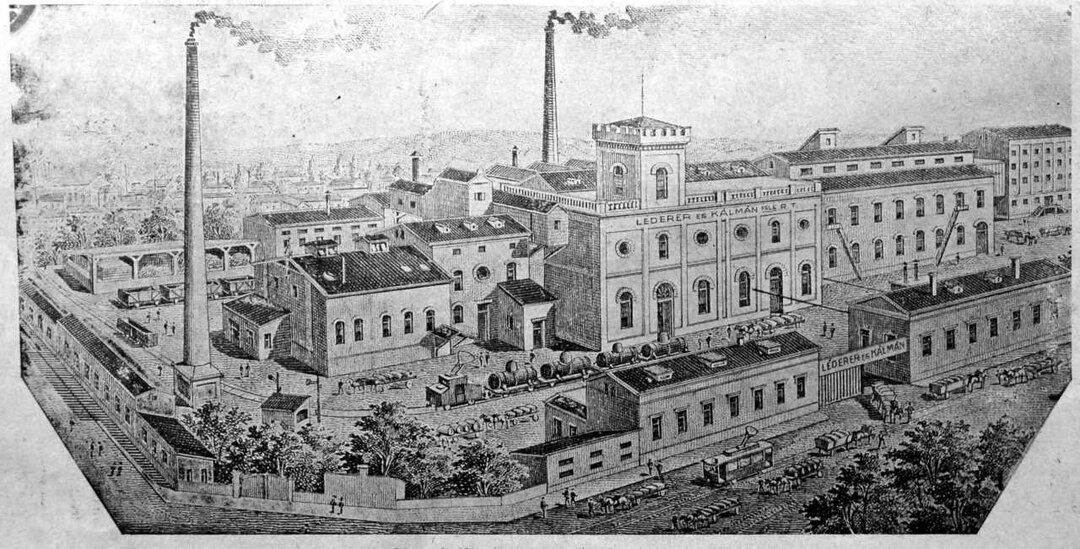

In the 14th century, the new royal castle of Diósgyőr was erected on the site of the first rudimentary castle of the 13th century, based on an Italian model with a regular geometrical plan.

The restoration work carried out over 40 years has maintained the ruin-like quality of the building. The successive use of materials confirms information about the details of the castle. In the case of missing stone fragments, whose shape and position have been identified, artificial stone was used. Where it was necessary to add details for the comfort of visitors, such as stairs or railings, metal was used. Thus, the main stages in the history of the castle can be identified. The original construction could be understood through well-designed details.

The recent restoration of the interior of the castle fell into a totally different paradigm, opposite to the previous approach. The enclosure walls of the castle were elevated despite the lack of information about the facades. The restoration of unknown details turned the castle into a fake hiding the original ruins, making further research almost impossible. The previous intervention reflected the avant-garde spirit of modern architecture, but the new solution does not aim to become architecture. Even the Gothic hall was reconstructed as a copy.

Although it is the largest Gothic hall in Central Europe, it was built at the beginning of the 21st century. The hall can indeed be used today, but the emphasis should have been on quality contemporary architecture.

There were probably enough clues and fragments found that the vault and the entire interior space could be reconstructed, but there was no information about the facades on the second floor. The restoration of the façades is therefore a conjunctural intervention. The whole building has become a pale and inert reproduction of an unknown original, devoid of the historical value of its era - a fun Disneyland for mass tourism, which only destroys the previous valuable intervention, an example of sophisticated modern architecture. (Fig. 4)

Conclusion

The value of the restorations carried out in the 1960s and 1970s must be preserved and conserved as a heritage of our architecture. It is imperative to accept this idea because the new interventions pose a threat to the previous ones. The restoration works of the 20th century - like those of the 19th century - should not be 'corrected' (just because we disagree with them), but analyzed and evaluated in the same way as all other early layers of the history of buildings, in order to preserve the authenticity of the past as a whole, which must include the 20th century interventions.

References

Ádám Arnóth, Zsuzsanna Lörinczi, Gábor Winkler and others: Architectural Guide of the 20th century of Hungary, 6Bt (2003)

This article is the edited version of a paper presented at the Conference of the ICOMOS International Scientific Committee on the Theory and Philosophy of Conservation and Restoration, Florence 2016.