Arhitectura la maximum (și la minimum)

Architecture to the maximum (and minimum)

| 1. Mare?

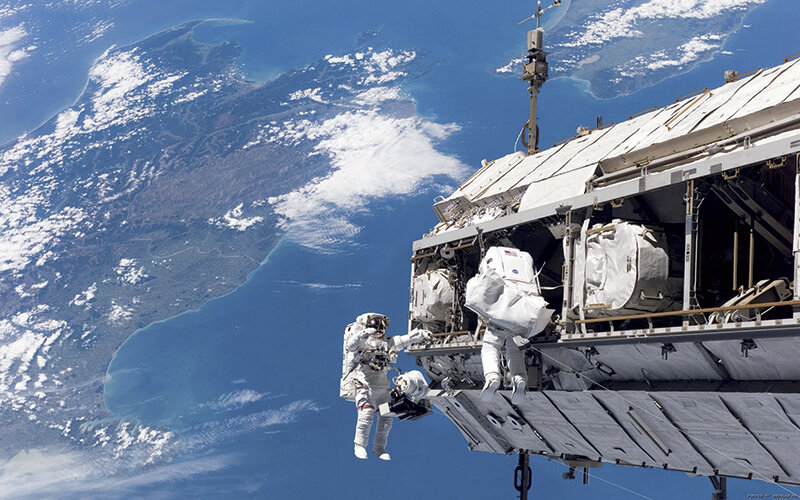

Un articol din Le Monde (19 aprilie 2005, p. 27) vorbește despre statutul - comercializabil sau nu - al monumentelor Greciei antice. Disputa ne interesează mai puțin aici. Mult mai interesante sunt două indicii pe care articolul ni le furnizează despre dorința, renăscută, de familiarizare cu clasicitatea a lumii contemporane, în secțiuni întâmplătoare, în fond, ale ei. Primul indiciu ne vorbește despre dorința firmei Vodafone de a găzdui o cină pentru 150 dintre conducătorii ei în porticul lui Attalos din Agora ateniană. Al doilea indiciu ne vorbește despre Rhodos și despre dorința cea mai mare a unui primar de pe insulă, în fine realizabilă mulțumită unei conjuncturi. În joc este nici mai mult, nici mai puțin decât reconstruirea Colosului din Rhodos, prăbușit în 227 î.H., în urma unui cutremur extrem de violent. O superproducție filmică, pe numele ei O, Jerusalem!, de Elie Choraqui, având a se turna acolo, a redeschis discuția cu privire la refacerea dezastrului de acum peste două milenii. Argumentele primarului sunt solide și țin deopotrivă de identitatea locală, ca și de atracția turistică: una e să intri cu feribotul într-un port grecesc oarecare și alta să o faci pe sub picioarele unui colos care se prenumăra, la vremea sa, printre minunile lumii antice. Avem așadar două cazuri: un monument antic existent, ba, mai mult, proaspăt restaurat, care este râvnit drept topos al unei cine de întreprindere; apoi, avem cazul unui monument despre existența căruia există date sigure, furnizate deopotrivă de texte ca și de arheologia submarină, a cărui absență pare să dateze de „ieri” și, prin urmare, ar trebui supus reconstrucției. În amândouă cazurile avem de-a face, din rațiuni diferite, cu o aceeași relație de „intimitate” temporală și spațială cu monumentul antic, care poate fi supus iminenței unor acțiuni cotidiene obișnuite: adăpostirea în vederea nutririi și repararea în vederea re-conferirii de statut simbolic unei comunități. Dar cea mai stranie relație cu trecutul ne-a propus-o tot Grecia, nu cu mult în urmă, dacă e să judecăm după standardele a ceea ce înseamnă „ieri” acolo. Pentru a explica semnificația gestului contemporan, trebuie, la rândul nostru, să ne întoarcem în timp până „ieri” și să citim introducerea la una din cărțile de arhitectură ale lui Vitruvius, unde apare personajul Deinocrates. Dar, până atunci, un scurt ocol. Arhitectura învăluie ființa și, precum veșmântul, este „croită” cel mai adesea pe măsura celui dinlăuntru: zeu, dacă e templu, și om, dacă este locuință. Măsura este aici un cuvânt-cheie. Închipui o casă pentru zeu? - cată atunci să arăți aceasta: zidărie ciclopică, sfântă a sfintelor, nemăsurare și absență întunecată. Alteori, templul hipetru (fără plafon și acoperiș), Vitruvius ne-o spune, este pentru stăpânii luminii și ai cerului în genere, unde cella rămâne deschisă, pentru ca ochiul zeiesc să se privească pe sine. Oricum ar fi, trebuie ținut seamă de scara altarelor: „pentru Jupiter și toți ceilalți zei cerești, să fie cât mai ridicate. Pentru Vesta și pentru zeii Pământului și ai Mării, să fie așezate mai jos” (Vitruvius, IV, 9: 3-4), astfel încât zeul să se reflecte în chipul casei sale. Această adecvare a scării arhitecturii la menirea sa - „măsura absolută” (Michelis: 1982, 208) - are de-a face cu măsurile ființei/corpului dinlăuntru. Dar nu asemenea proiecte reprezintă rețeta monstruozității, ci antropomorfizarea peisagiului însuși, un hybris încă mai violent. Această terraformare - luare în deșert, în răspăr a facerii, aici văzută ca incompletă - își are probabil cel mai lămuritor exemplu în viziunea lui Deinocrates. Acesta i-a propus lui Alexandru sculptarea Muntelui Athos în chip de statuie ținând în stânga un oraș, iar în dreapta un bol în care să se fi strâns toate apele muntelui. Asemenea viziune este numită de Oechslin, parafrazându-l pe Josef Ponten din a sa Architektur die nicht gebaut wurde (1925), o „idee monstruoasă în chip babilonic, colosală în chip oriental” (1993: 473). Ea a generat interpretări dintre cele mai felurite, de la Filarete și Alberti la Fischer von Erlach. Un soi de împliniri parțiale, desfigurate, ale sale pot fi considerate Colosul din Rhodos, statuile de președinți sculptate în Mount Rushmore, Palatul Sovietelor și Canalul Volga-Don, cu giganții Stalini veghind terraformarea URSS prin munca silnică a deținuților politici. Avem în ideea lui Dinocrates un exemplu originar al frisoanelor de gigantism care străbat din vreme în vreme arhitectura. Sunt ele forme paranoice de antropomorfism sau reziduuri ale vremilor când pământul era locuit de uriași, ei înșiși un proiect inițial, avortat, de umanitate? Trebuie, poate, să recitim cele cinci teoreme despre Big-ness, ale lui Rem Koolhas, ca să înțelegem cât de depar-te conceptual a ajuns supradimensionarea arhitecturii care intră, astfel, în regimul estetic al sublimului (unde, de altfel, o trimisese Hegel, cu piramidele ca exemplu?) Iată fragmentul în care, din textul vitruvian, respiră vocea lui Dinocrates: „Căci am plănuit să sculptez Muntele Athos în chip de statuie bărbătească, punându-i în mâna stângă zidurile unei cetăți uriașe, iar în cea dreaptă o cupă care să primească apa tuturor râurilor din acest munte, pentru ca din ea să se verse în mare” (Vitruvius, II, Prefață, 2). Din perspectiva relației chip-trup/arhitectură, gigantismul și nelimitarea declamă, de regulă, voința puterii de a fi reprezentată prin zidiri ne-umane. Alexandru a refuzat propunerea lui Deinocrates, dar urmașii săi vor fi mai atenți la propuneri similare, de nu le vor fi provocat ei înșiși. Acum iată știrea publicată și la noi de România literară (41/16-22 octombrie 2002): „O fundație greco-americană a inițiat proiectul de a ciopli pe versantul unui munte din nordul Greciei un portret gigantic al lui Alexandru cel Mare. Conform promotorilor ei, această sculptură de 80 de metri înălțime și 57 lățime «ar întări caracterul grec al Macedoniei» și ar atrage turiști (ansamblul, care va costa cam 30 milioane de euro, prevede în preajmă un muzeu, un amfiteatru și parking). Versiunea elenică a Muntelui Rushmore a obținut aprobările oficiale, dar nu toți sunt încântați (...), iar arheologii și ecologiștii o consideră de-a dreptul monstruoasă și amenință cu sesizarea justiției”. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 5/2012 al revistei Arhitectura. |

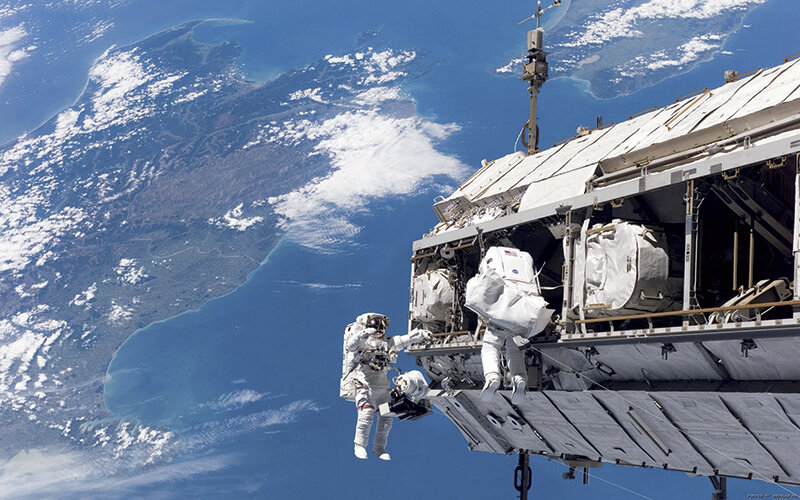

| 1. Big?

An article in Le Monde (19 April 2005, p. 27) talks about the status of ancient Greek monuments and whether or not they can be commercialised. The arguments are not what interest us here, but rather the two clues that the article provides us about the contemporary world’s renascent desire for familiarity with ultimately random sections of the classical world. The first clue is the intention on the part of Vodafone to hold a dinner for 150 of its company leaders in the portico of Attalos in the Athenian Agora. The second clue concerns the Island of Rhodes and the intentions of one of its mayors, which has finally become achievable thanks to a conjunction of circumstances: what is at stake is nothing less than the rebuilding of the Colossus of Rhodes, which was destroyed by a violent earthquake in 227 B.C. Production of a big-budget film by Elie Choraqui, called O, Jerusalem!, due to be shot on Rhodes, has reopened the debate about repairing the disaster of more than two millennia ago. The mayor’s arguments are solid and relate both to local identity and to creating a tourist attraction: it is one thing to arrive by ferry in an ordinary Greek port and quite another to dock beneath the legs of a colossus, a recreation of one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. Thus we have two cases: an extant and even recently restored ancient monument, sought after as the topos for a business dinner; and the case of a monument for whose existence there is clear evidence, in the form of both ancient texts and marine archaeology, and whose absence seemingly dates from just “yesterday” and so demands reconstruction. In both cases, but for different reasons, we are dealing with the same relationship of temporal and spatial “intimacy” with an ancient monument, which can be subjected to the immanence of ordinary everyday activities: the setting for a meal and reconstruction with a view to restoring a community’s symbolic status. It was also Greece that offered us not so long ago one of the strangest examples of the relationship with the past, if we are to judge by the standards of what “yesterday” means over there. In order to explain the meaning of the contemporary gesture we shall have to go back in time to “yesterday” and read the introduction to one of Vitruvius’ books on architecture, the one that mentions Deinocrates. But first let us make a short digression. Architecture envelops being and, like a garment, it is most often “tailored” to fit the measure of the person inside: a god, if it is a temple, or a man, if it is a dwelling. Measure is the keyword here. Are you designing a house for a god? Then you need to display the following: cyclopean masonry, a holy of holies, boundlessness, and tenebrous absence. Sometimes, Vitruvius tells us, the hypethral (roofless) temple is dedicated to the lord of light and the heavens in general, and the cella is open to the sky so that the eye of the god can gaze upon itself. Whatever the temple might be, the scale of the altars needs to be taken into account, so that the god will be reflected in the image of his house: “For Jupiter and all the other heavenly gods they should be as elevated as possible. For Vesta and the gods of the Earth and Sea they should be positioned lower” (Vitruvius, IV, 9, 3-4). This appropriateness of architectural scale (“absolute measure”, Michelis: 1982, 208) relates to the measure of the being/body within. However, it is not such designs that represent a recipe for monstrosity, but rather the anthropomorphising of the landscape itself, a hubris that is all the more violent. Such terraforming - taking creation in vain, against the grain, viewing it as incomplete - probably finds its best illustration in the vision of Deinocrates. He proposed to Alexander that he should carve Mount Athos in the shape of a statue holding a city in its right hand and in its left a bowl that would gather all the mountain’s waters. In his Architektur die nicht gebaut wurde (1925), paraphrasing Josef Ponten, Oechslin calls it “an idea Babylonian in its monstrosity, oriental in its vastness” (1993: 473). It has given rise to the most various interpretations, from Filarete and Alberti to Fischer von Erlach. The Colossus of Rhodes, Mount Rushmore, the Palace of the Soviets, and the Volga-Don Canal, with its gigantic Stalins keeping watch over the terraforming of the USSR through the forced labour of political prisoners, may all be regarded as partial, distorted fulfilments of Deinocrates’ idea. In that idea we find an original example of the fever for gigantism that periodically grips architecture. Are they paranoid forms of anthropomorphism or the residues of times when the earth was inhabited by giants, themselves an abortive prototype of mankind? Perhaps we should reread Rem Koolhas’s five theorems of Bigness in order to understand how far oversized architecture has come, thereby entering the aesthetic realm of the sublime (where else did Hegel refer it, using the pyramids as an example?). Here is the passage from Vitruvius which reproduces the voice of Deinocrates: “For, I planned to carve Mount Athos in the form of a male statue, holding in his left hand the walls of a huge city, and in his right hand a cup to gather the waters of all the mountain’s rivers and thence empty them into the sea” (Vitruvius, II, Preface, 2). From the perspective of the body/architecture relation, gigantism and boundlessness usually proclaim the will to be depicted in non-human masonry. Alexander rejected Deinocrates’ proposal, but his successors would be more receptive to similar proposals, that is, when they themselves did not prompt them. And now here is an item of news published in Literary Romania (no. 41, 16-22 October 2002): “A Greek-American company has set underway a project to carve a gigantic likeness of Alexander the Great into the slope of a mountain in northern Greece. According to its sponsors, the eighty-metre-high and fifty-seven-metre wide sculpture ‘will reinforce the Greekness of Macedonia’ and attract tourists (the complex, which will cost around thirty million euros, will include a museum, amphitheatre, and car park). The Hellenic version of Mount Rushmore has been granted official permits, but not everybody is happy… archaeologists and ecologists view it as a monstrosity and are threatening legal action”. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |