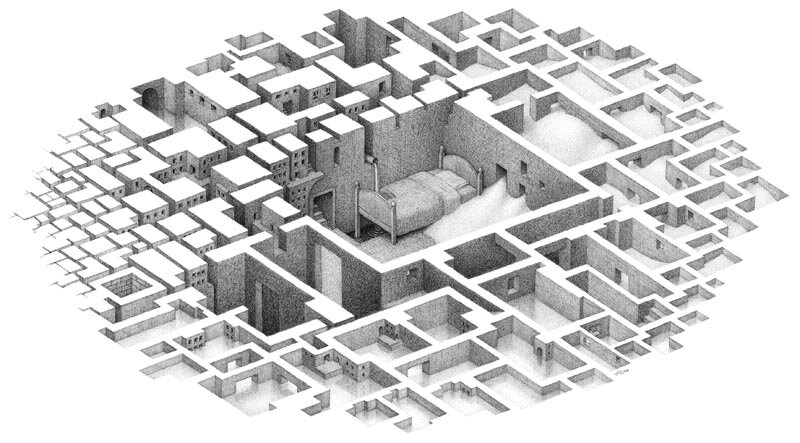

Desenul de mână ca mijloc de identificare a greșelilor arhitecturale și dezvoltarea unei noi percepții asupra arhitecturii

Hand drawings for new perception and mistakes in architecture

| La începutul secolului trecut, Duchamp a transformat lumea artei prin afirmarea posibilității de a produce artă fără intervenția mâinilor. Arta putea sau trebuia să fie creată prin aplicarea conceptuală complicată a unor idei sau teorii conceptuale, fapt care a devenit mai important decât reprezentarea fizică a artei înseși. Prin actul de a transforma bucăți de material, de a selecta obiecte existente, de exemplu, pentru a le transforma esența reală, li se insufla acestora o nouă viață și noi sensuri fără a se recurge la vreo operațiune manuală specială. Această revoluție a fost incredibil de importantă și a afectat numeroase aspecte ale artei, dintre cele mai diverse. Artiștii nu mai erau obligați să își folosească mâinile pentru a produce ceva special; ei puteau folosi metoda „conceptualizării” ideilor pentru a crea artă. Această teorie a revoluționat nu doar lumea fizică a artei, ci și, mai presus de toate, percepția pe care oamenii o aveau despre artă și percepția pe care arta o avea cu privire la oameni.

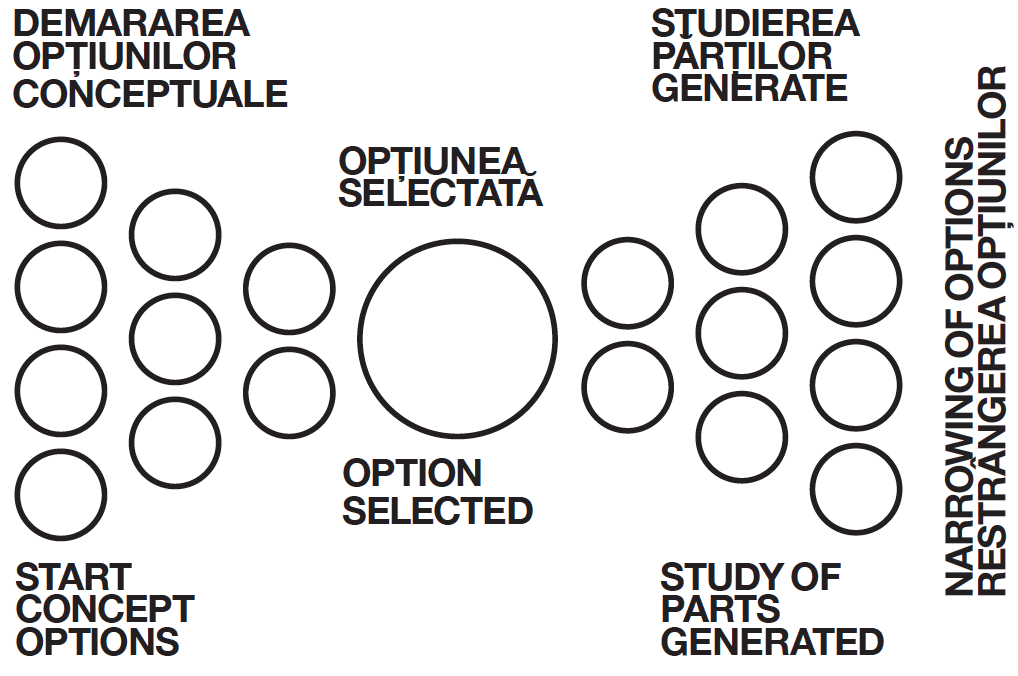

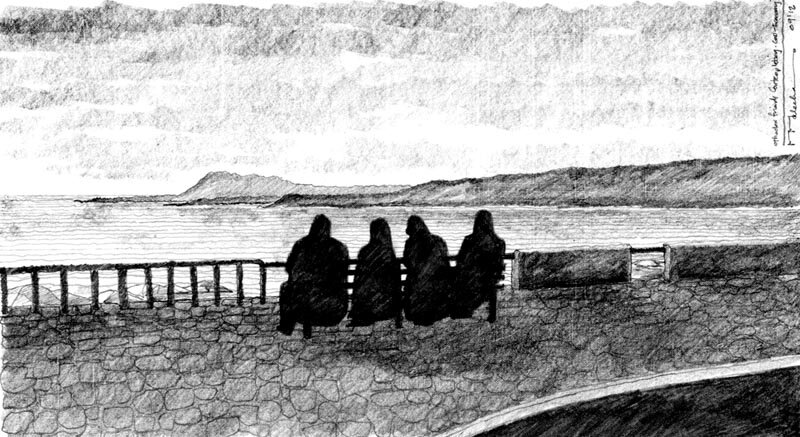

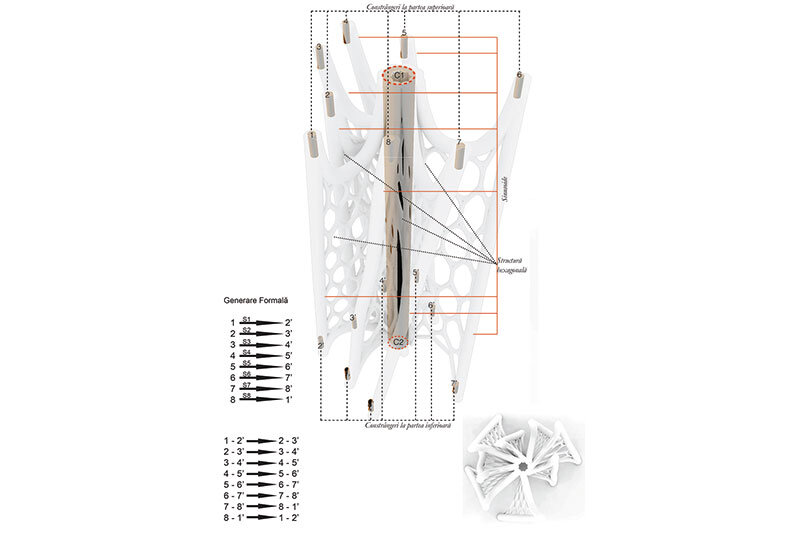

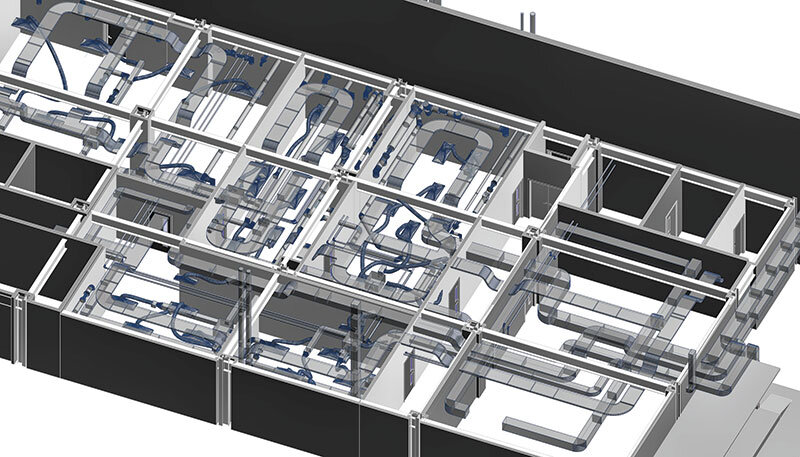

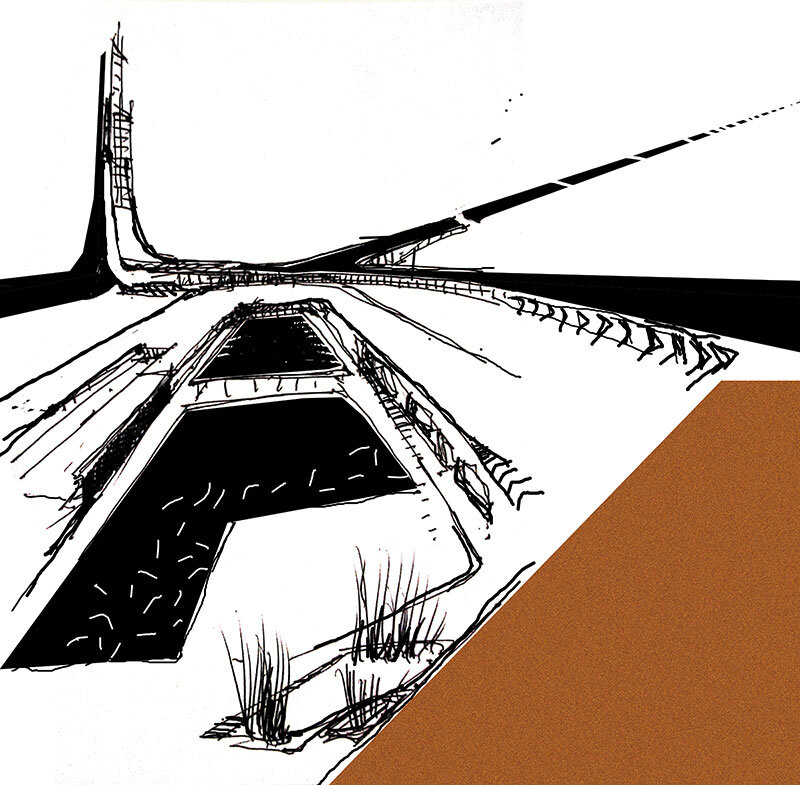

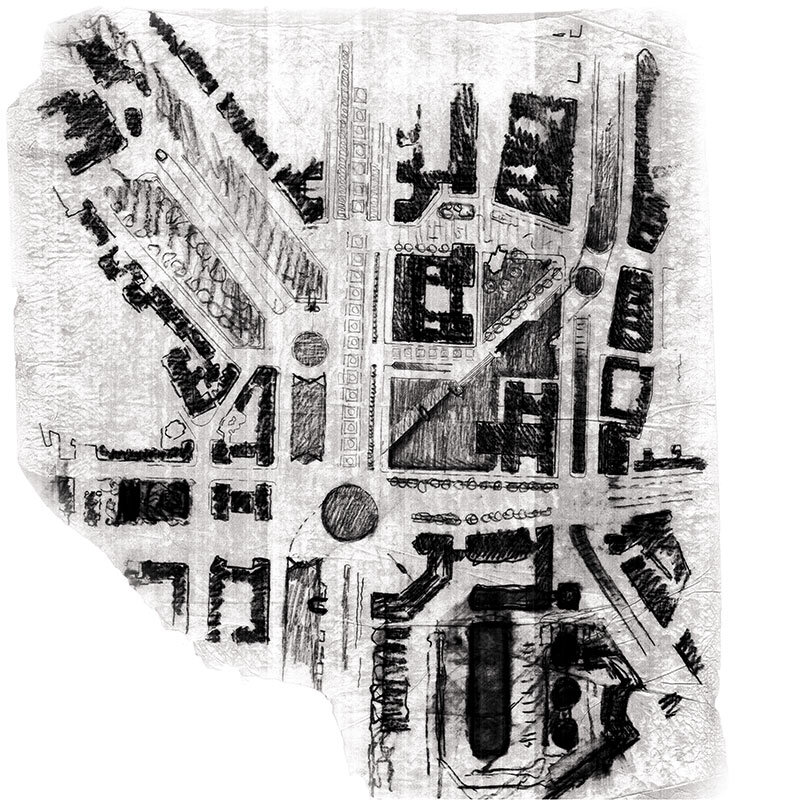

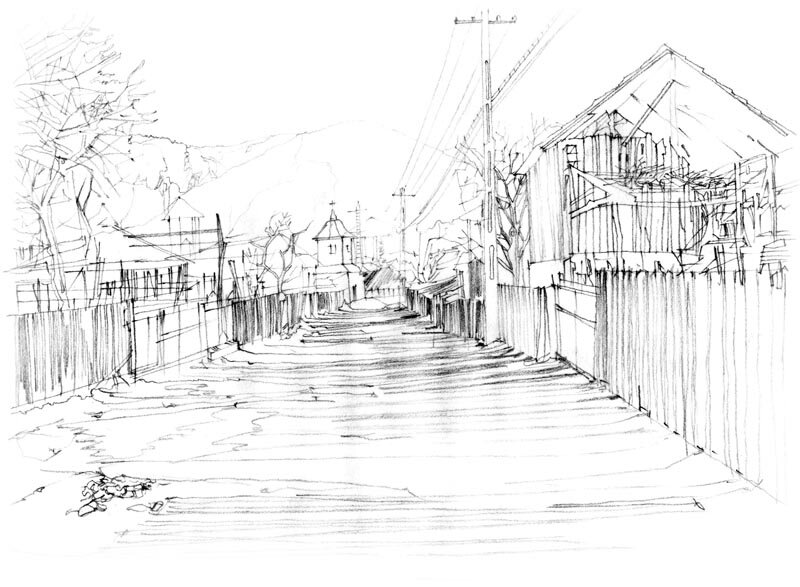

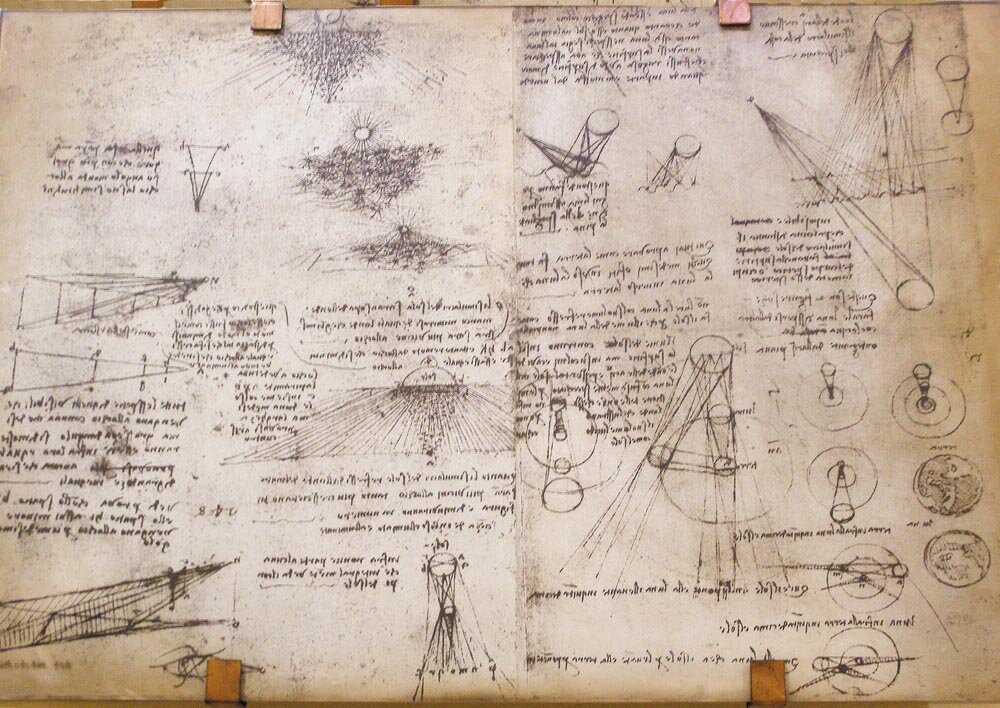

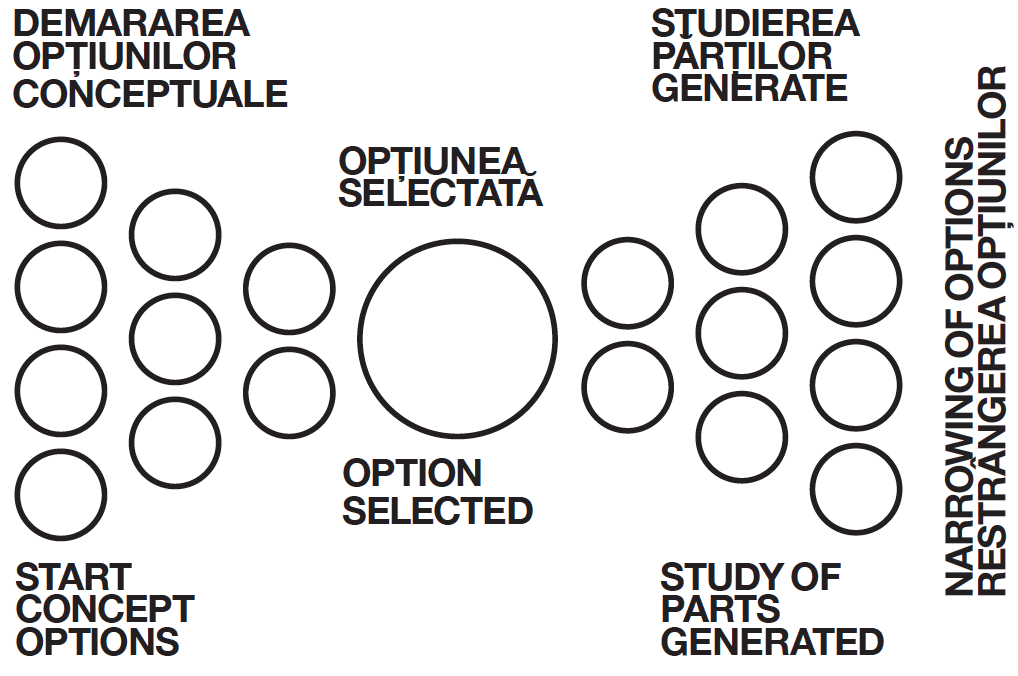

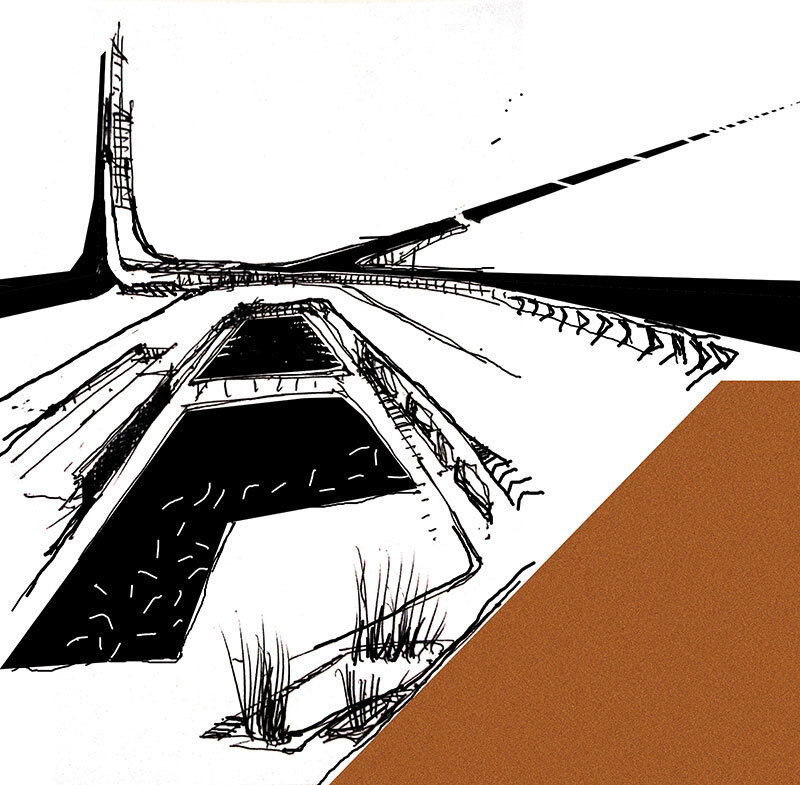

Deși, dacă ne gândim la „Roata de bicicletă”, unul dintre cele mai faimoase obiecte ready-made ale lui Duchamp, întrebuințarea imperativă a mâinilor pentru a împrumuta acestui obiect expresia dinamică a esenței artei a fost importantă și fundamentală. În acea perioadă, nu am asistat la aceeași dihotomie în arhitectură deoarece conceptele și desenele de mână făceau parte din același proces în percepția, proiectarea și reprezentarea arhitecturii. Arhitecții încă mai utilizau desenul de mână pentru a-și dezvolta ideile, urmând evoluția proiectării prin forme generate de producția de schițe și note, utilizate, în general, în paralel cu schițele. Schițele robuste, esențializate și mai puțin atractive ale lui Le Corbusier, magnificele reprezentări arcadiene ideale ale arhitecturii realizate de Wright sau spațiile plate, precise, gestionate cu măiestrie poetică de către Mies sunt doar câteva exemple simple, clare și indubitabile ale unei conexiuni puternice între desenele manuale, desenele tehnice și proces în arhitectură. Álvaro Siza scria în 1987: „Pentru arhitect, desenul este un instrument de lucru, o formă de învățare, de asimilare, de comunicare și de transformare: este o metodă utilizată în procesul de proiectare. Arhitectul mai are la dispoziție și alte instrumente, dar nimic nu poate lua locul desenului fără a avea consecințe negative. Conceperea unui spațiu organizat și abordarea calculată a situației existente și a celei pe care sperăm să o obținem în acesta sunt filtrate de intuițiile pe care desenul le generează instantaneu în cele mai logice construcții asupra cărora s-a convenit, astfel contribuind la nașterea acestora. Fiecare gest pe care îl facem, inclusiv desenul, este încărcat de istorie, memorie inconștientă și înțelepciune incomensurabilă și necunoscută. Desenul ar trebui să fie practicat în așa fel încât fiecare gest al nostru și orice altceva să nu devină atrofiat”. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 1 / 2014 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| Duchamp, at the beginning of the last century, transformed the world of Art asserting the possibility to produce art without using the hands. Art could or must be created through a complicate conceptual application of ideas or conceptual thoughts, which became much more important than the physical representation of the art itself. At least, the action to transform pieces of real material, picking existing objects up, for example, in order to transform their real essence, was an act to give them new life and meanings without involving any particular actions by hands. The revolution was incredibly important, and afflicted many different aspects of art; artists had not had any more the necessity to be special in using their hands, but they could use the “technique” of conceptualization of ideas to create art. This theory, not only have revolutionized the physical world of the art but, above all, the perception that people had about art, and the perception that art had towards people.

Although, thinking about “The Bicycle Wheel”, one of the most famous Duchamp’s ready-made, the imperative use of the hands to give to this object the dynamic expression of the essence of its art, was important and fundamental. In that period, we did not assist to the same dichotomy in architecture because concepts and hand drawings were part of the same process in perception, design, and representation of architecture. Architects still used the hand drawings to develop ideas, following the evolution of the design through forms that came out from the production of sketches and notes, usually used next to the sketches. Le Corbusier’s strong, basic, and less attractive sketches, the stunning ideal Arcadian representation of the architectures by Wright, or the precise flat spaces managed with poetry by Mies, are just only a few simple, clear, indubitable examples of the strong connection between the hand drawings, technical drawings and process in architecture. Álvaro Siza in 1987, wrote: “For the architect, drawing is a work tool, a form of learning, assimilation, communication and transformation: it is a method used in the design process. The architect also has other tools available, but nothing can take the place of drawing without leading to negative consequences. The ideation of an organized space and the calculated approach taken to the existing situation and what one hopes to achieve there are all filtered through the intuitions that drawing feeds instantaneously into the most logical and agreed upon constructions, thereby nourishing them. Every gesture that we make - including drawing - is charged with history, unconscious memory, and incommensurable and unknown wisdom. Drawing should be practiced so that our every gesture and everything else does not become atrophied”. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |