Ghid de desenat 101: informații, nu detalii

Sketching 101: Information, not detail

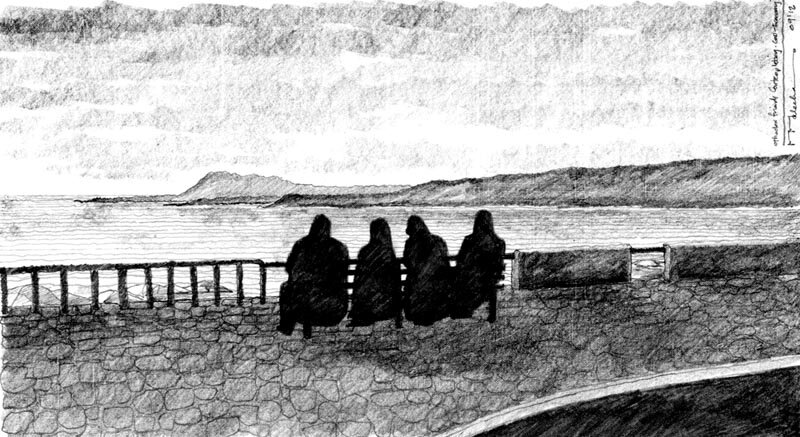

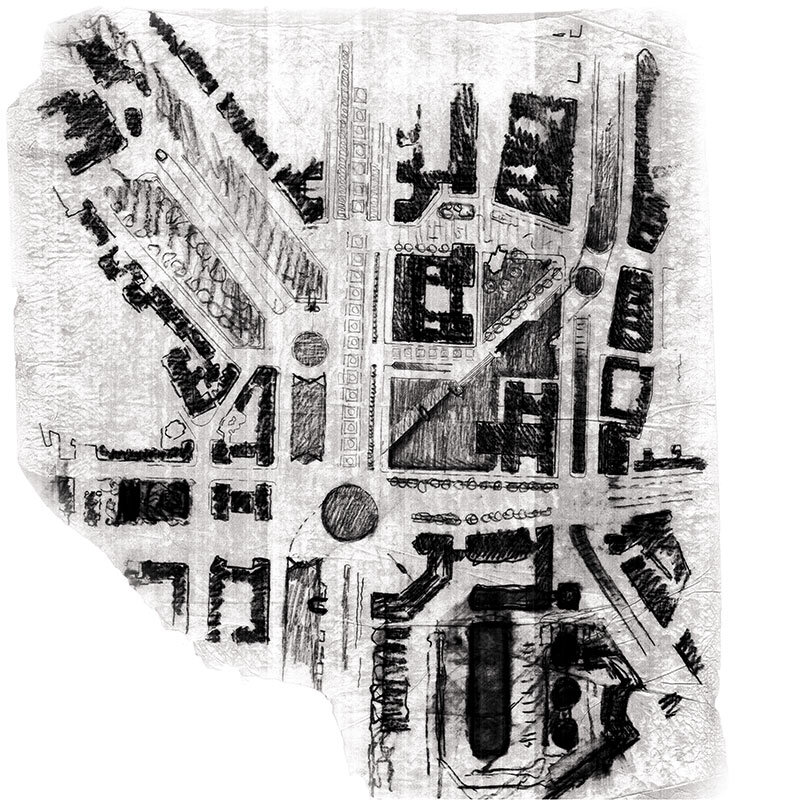

| De ce atât de mulți arhitecți continuă să deseneze atunci când călătoresc?1 Este adevărat că există unele situații când ne convine mai mult să realizăm rapid un desen - de exemplu, atunci când ne aflăm în medii în care fotografiatul este interzis - însă atașamentul nostru neîntrerupt față de desen pare să răspundă, mai degrabă, unor dorințe care nu sunt satisfăcute de versatilitatea digitală a camerelor foto portabile, a tabletelor și smartphone-urilor pe care le ducem cu noi prin buzunare și genți.Desenăm pe blocuri de desen în acuarelă și pe simple caiete de schițe, pe șervețelele din baruri și pe fețele de masă din restaurante; pe pungile pentru rău de avion2 sustrase din buzunarul scaunului din fața noastră, pe interiorul pachetelor de țigări goale, pe spatele plicurilor și al cărților de vizită și, da, chiar și pe smartphone-uri și tablete. Ținem jurnale în care ne consemnăm reflecțiile profunde referitoare la călătoriile noastre și realizăm desene spontane în creion și ne umplem agendele, unde notăm, de obicei, orarul trenurilor și adresele de e-mail, cu schițe stilizate și desene în peniță ale unei case de Horia Creangă sau ale unui bloc de Tiberiu Niga.

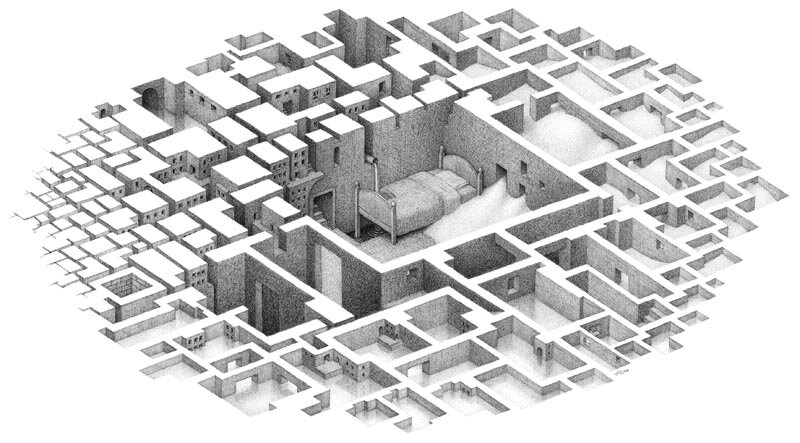

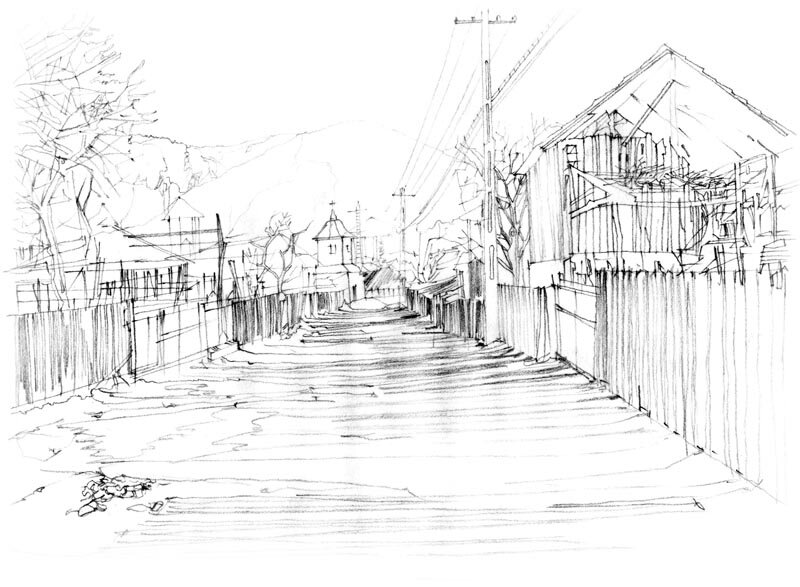

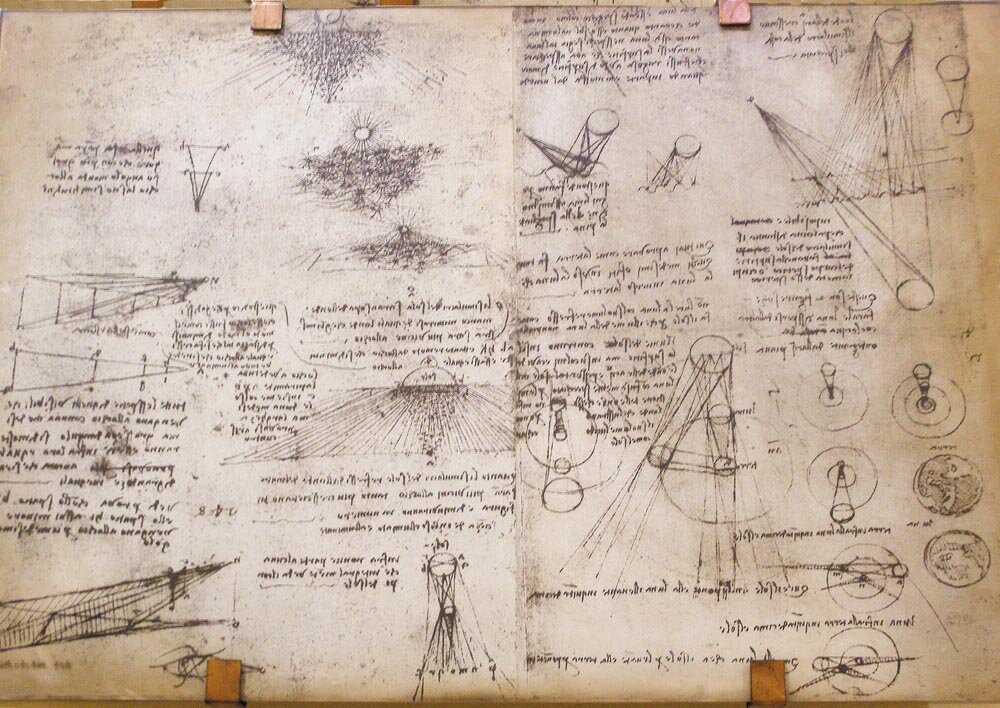

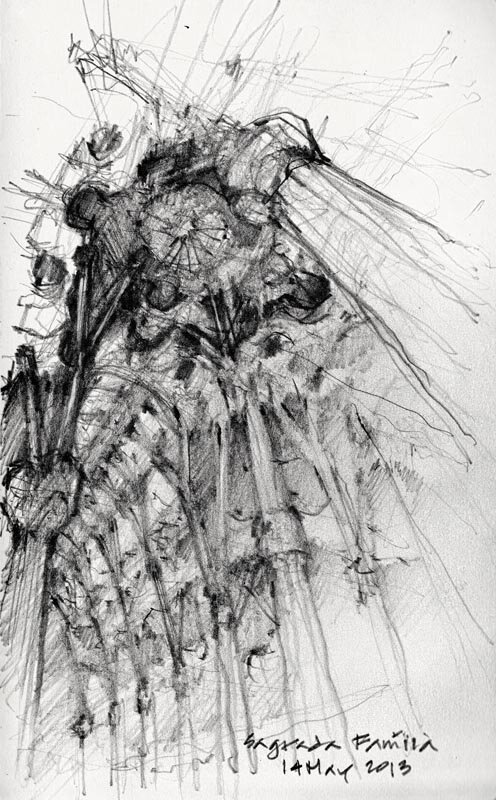

Efectuarea acestor desene presupune timp; unele sunt finalizate în câteva minute, în timp ce altele durează mai mult. Mai scurt sau mai îndelungat, procesul definește o relație cu locul respectiv care nu este, de obicei, posibilă în cazul altor forme de documentare, cum ar fi tabletele și majoritatea aparatelor de fotografiat, care se interpun literal între observator și obiect. Ritualurile asociate cu desenul pun baza pentru întâlnirea noastră cu mediul care ne interesează. Desenele pe care le producem consemnează nu doar ceea ce am văzut, ci și ceea ce gândeam și cea ce am învățat. Ele nu sunt niște vederi; ele sunt mărturia curiozității noastre și a încercărilor noastre de a înțelege ideile care ne modelează lumea. Credința noastră în valoarea formelor tradiționale de desen este uneori dezvăluită de anumite metafore care compară acest tip de desen cu expresii mai puțin controversate ale artei și ideilor. În Pedagogical Sketchbook, Paul Klee introduce imaginea captivantă a desenului ca „O linie activă care hoinărește nestingherită, fără nicio țintă”3. În eseul de final pe care l-a scris pentru lucrarea Tools of the Imagination, editată de Susan Piedmont-Palladino, William J. Mitchell plasează hoinăreala menționată de Klee pe un fundal muzical, atunci când sugerează că „A desena nestingherit seamănă cu a dansa pe hârtie”4. Arhitecții Le Corbusier și Antoine Predock au dus această discuție dincolo de metaforă. În mod deloc surprinzător, Le Corbusier are un punct de vedere lipsit de ambiguități pe această temă. „Atunci când călătorești și lucrezi cu obiecte vizuale - arhitectură, pictură sau sculptură - îți folosești ochii și desenezi în așa fel încât să ancorezi într-un mod cât mai temeinic în experiența proprie ceea ce vezi. Odată ce impresia a fost consemnată, înregistrată, înscrisă cu creionul, ea rămâne pentru totdeauna. Camera foto este un instrument pentru leneși, care folosesc o mașinărie care să vadă pentru ei. Să desenezi tu însuți, să trasezi linii, să gestionezi volumele, să organizezi suprafețele... toate acestea înseamnă mai întâi să privești, apoi să observi, iar în cele din urmă, poate, să descoperi… și acela este momentul în care poate apărea inspirația. Atunci când inventezi sau creezi, întreaga ta ființă este atrasă în acțiune și această acțiune este ceea ce contează.”5 |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 1 / 2014 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| NOTE:

1 Am început, de multe ori, conversații despre desen cu această întrebare. Acest articol include o documentare asociată cu anumite cursuri co-predate pe parcursul anilor de profesorii Stuart Wilson, Gentile Tondino, Ricardo Castro și Robert Mellin, precum și cu note de la conferința ce a avut loc la Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico, în 2007, și alte reflecții pe desen. 2 Schițele de proiectare ale arhitectului Renzo Piano, realizate pe pungile pentru rău de avion recuperate din nenumărate aeronave au fost publicate în majoritatea monografiilor recente dedicate operei sale. 3 Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, Faber and Faber, Londra, 1984, p. 16. 4 Susan Piedmont-Palladino, editor, Tools of the Imagination, Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2007, p. 117. 5 Le Corbusier, Journey to the East, editat și adnotat de Ivan Zaknic, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England 2007, p. xiv (Textul este citat de autor în prefața celei de-a doua ediții, exact așa cum a fost extras din Creation is a Patient Search a lui Le Corbusier). |

| Why do so many architects still sketch when they travel?1 It’s true that there are occasions when our ability to make a quick sketch is convenient - for example, when we find ourselves in environments where photography is forbidden - but our continuing love affair with sketching seems to address desires that are not satisfied by the digital versatility of the portable cameras, tablets and smartphones in our pockets and handbags.We sketch on watercolour blocks and in simple sketchbooks, on napkins in bars and on tablecloths in restaurants; we sketch on airsickness bags2 retrieved from the seat pocket in front of us, on the inside of empty cigarette packs, on the backs of envelopes and business cards, and yes, we even sketch on our smartphones and tablets. We keep journals that document our travels with thoughtful reflections and crisp pencil drawings and we fill notebooks where train schedules and e-mail addresses share the pages with gestural pen and ink sketches of a house by Horia Creangă or an apartment block by Tiberiu Niga.

Making these drawings takes time; some are completed in five minutes, others take longer. Short or long, the process defines a relationship with a place that is usually not possible with other forms of documentation - like tablets and most cameras - that literally come between the observer and the subject. The rituals associated with sketching add structure too our encounters with environments that interest us. The drawings that we produce record not only what we saw but also what we were thinking and what we learned. They are not just postcard; they are evidence of our curiosity and our attempts to understand the ideas that shape our world. Our faith in the value of traditional forms of sketching is sometimes revealed in metaphors that compare this kind of drawing to less controversial expressions of art and ideas. In Pedagogical Sketchbook, Paul Klee introduces the compelling image of a drawing as “An active line on a walk, moving freely, without goal”3. In the concluding essay that he wrote for Tools of the Imagination, edited by Susan Piedmont-Palladino, William J. Mitchell animates Klee’s walk with music when he suggests that “Drawing with a free hand is like dancing on paper”4. Architects Le Corbusier and Antoine Predock take the discussion beyond the metaphor. Le Corbusier is, not surprisingly, unambiguous on the subject. „When one travels and works with visual things - architecture, painting or sculpture - one uses one’s eyes and draws, so as to fix deep down in one’s experience what is seen. Once the impression has been recorded by the pencil, it stays for good, entered, registered, inscribed. The camera is a tool for idlers, who use a machine to do their seeing for them. To draw oneself, to trace the lines, handle the volumes, organize the surfaces… all this means first to look, and then to observe and finally perhaps to discover… and it is then that inspiration may come. Inventing, creating, one’s whole being is drawn into action, and it is this action which counts.”5 |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| NOTES:

1 I often start conversation about drawning whith this question. This article includes material associated with courses co-taught over the years with Professors Stuart Wilson, Gentile Tondino, Ricardo Castro and Robert Mellin, as well as notes from a conference presentation at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico, in 2007, and other reflection on drawing. 2 Architect Renzo Piano’s design sketches on the airsickness bags of numerous airlines have been published in most of the recent monographs on his work. 3 Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, Faber and Faber, London, 1984, p. 16. 4 Susan Piedmont-Palladino, editor, Tools of the Imagination, Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2007, p 117. 5 Le Corbusier, Journey to the East, edited and annotated by Ivan Zaknic, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England 2007, p. xiv (The text is cited by the editor in the Preface to the Second Edition as having been drawn from Le Corbusier’s earlier book Creation is a Patient Search). |