Drawing 101: information, not details

Sketching 101: Information, not detail

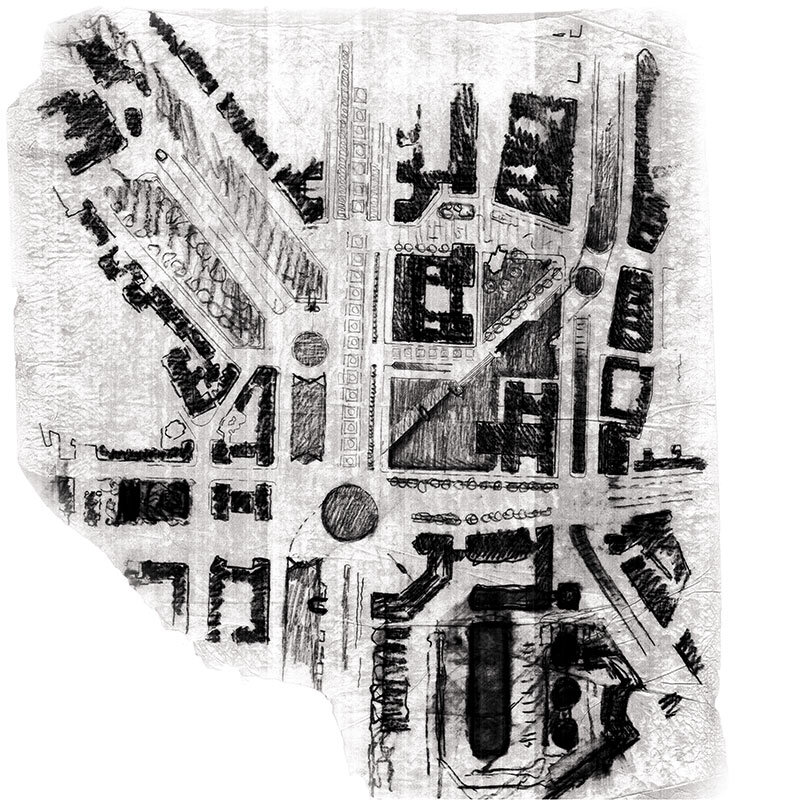

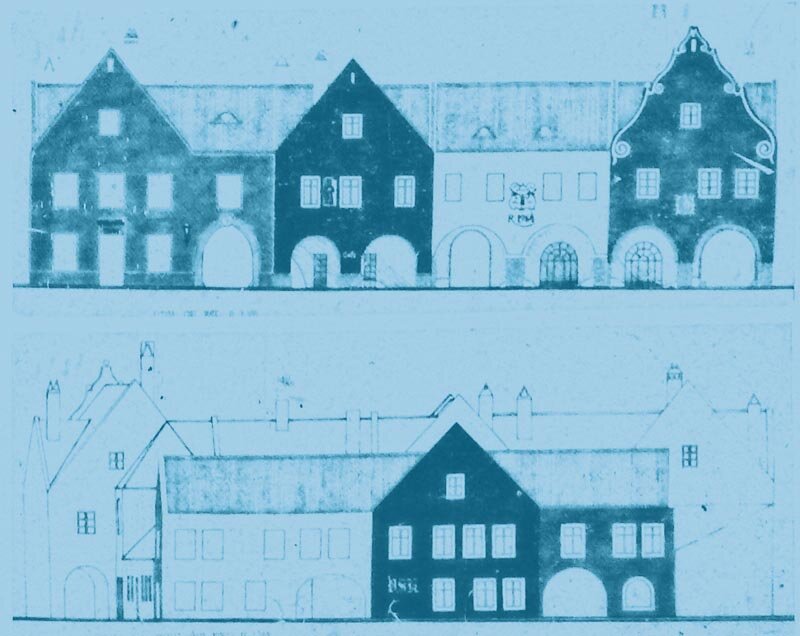

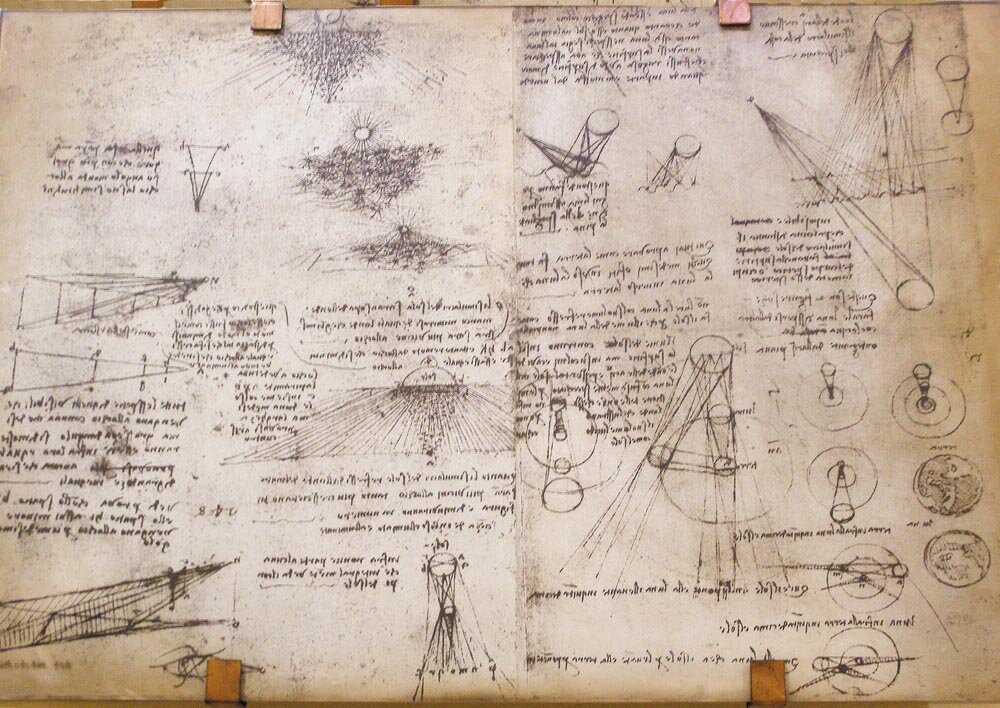

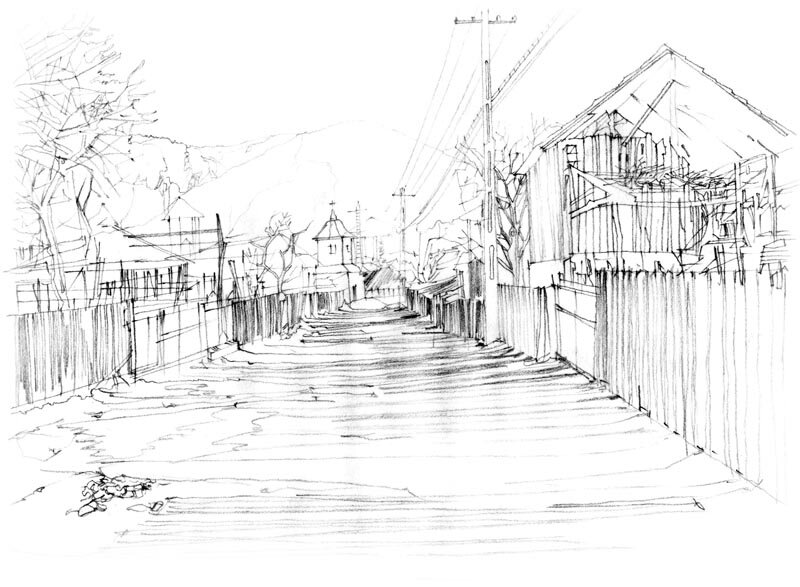

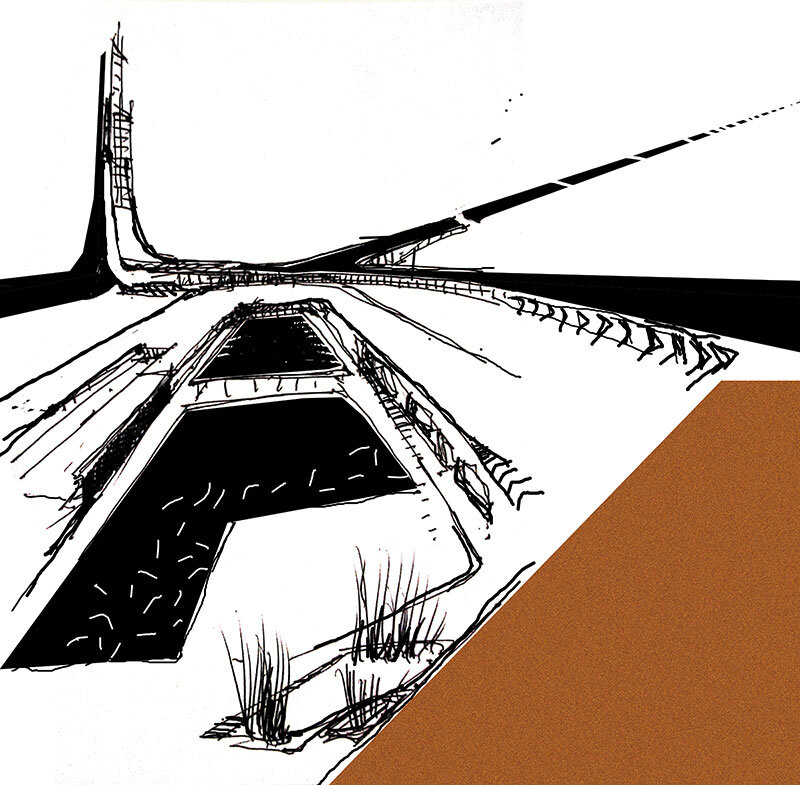

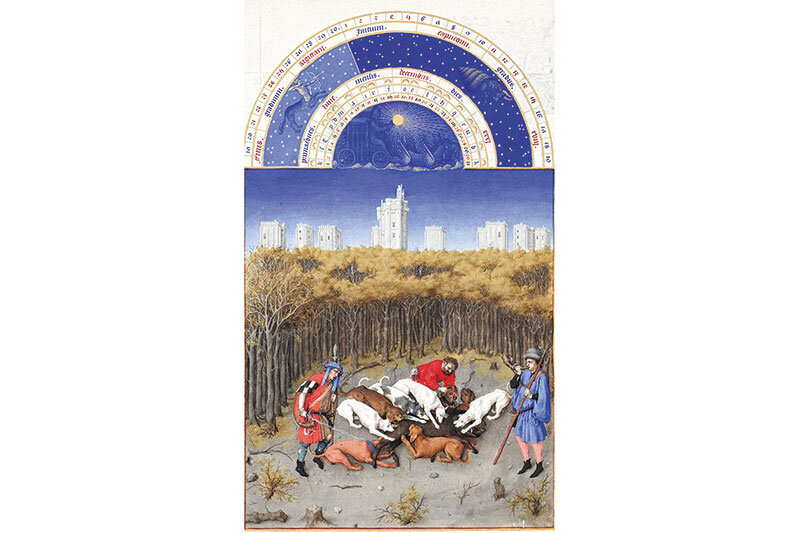

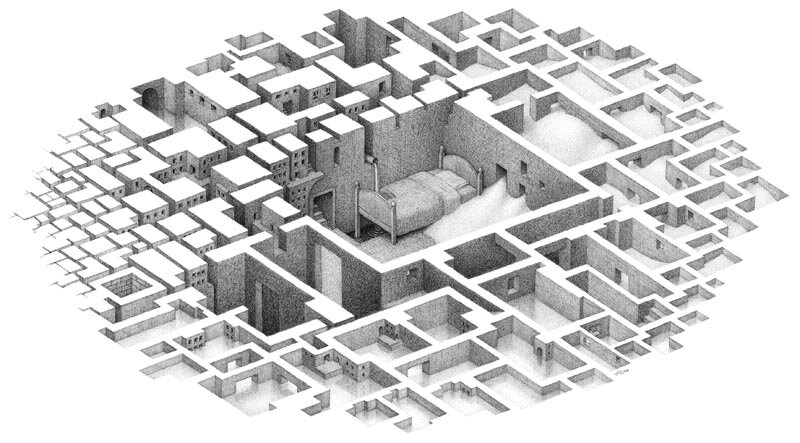

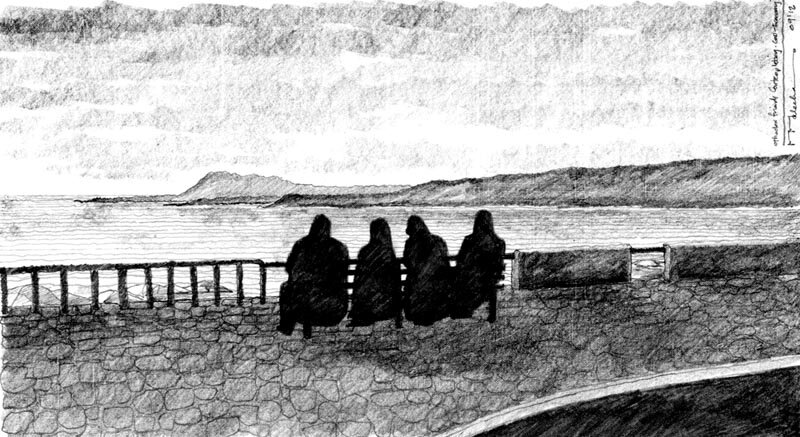

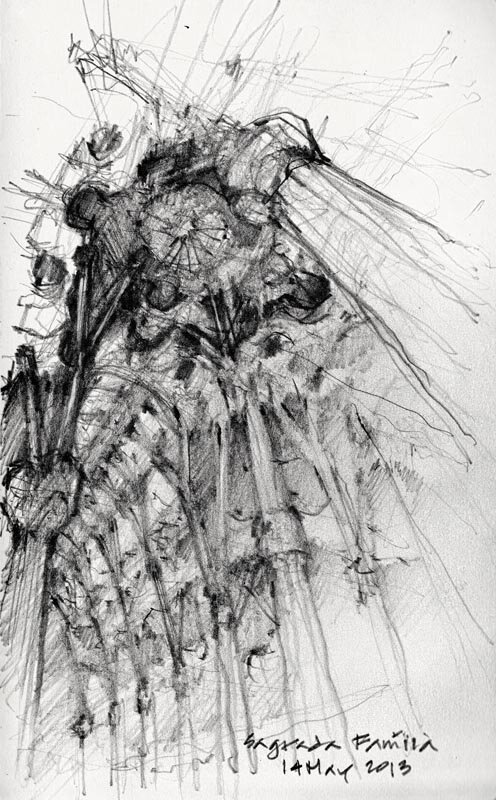

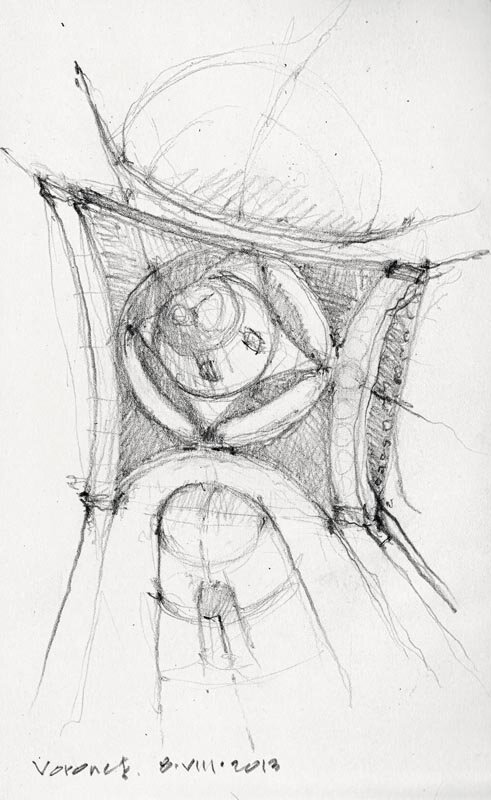

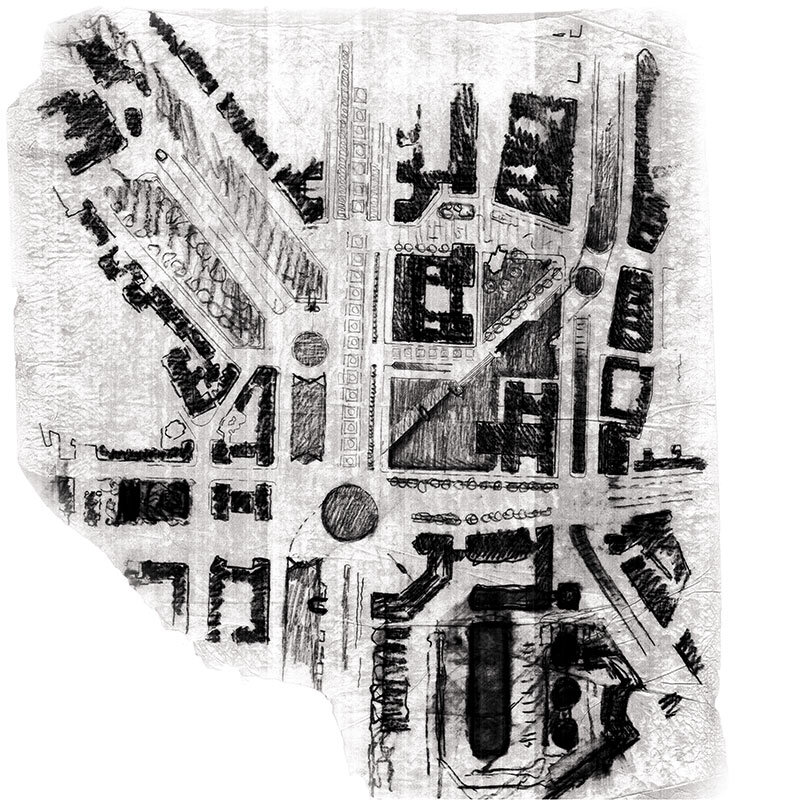

| Why do so many architects continue to sketch when traveling?1 It's true that there are some situations when it suits us better to produce a drawing quickly - for example, when we are in environments where photography is forbidden - but our unwavering attachment to drawing seems to be more likely to respond to desires that are not satisfied by the digital versatility of the hand-held cameras, tablets and smartphones we carry with us in our pockets and bags.We draw on watercolor sketchpads and simple sketchbooks, on bar napkins and restaurant tablecloths; on airsickness bags2 snatched from the seat pocket in front of us, on the inside of empty cigarette packs, on the backs of envelopes and business cards, and yes, even on smartphones and tablets. We keep diaries in which we record our deep reflections on our travels and make spontaneous pencil drawings and fill our diaries, where we usually note train schedules and email addresses, with stylized sketches and pen-and-ink drawings of a house by Horia Creangă or a block by Tiberiu Niga. Making these drawings takes time; some are completed in minutes, others take longer. Whether short or long, the process defines a relationship with place that is not usually possible with other forms of documentation, such as tablets and most cameras, which literally interpose themselves between the observer and the object. The rituals associated with drawing provide the basis for our encounter with the environment that interests us. The drawings we produce record not only what we have seen, but also what we have thought and what we have learned. They are not just views; they bear witness to our curiosity and our attempts to understand the ideas that shape our world. Our belief in the value of traditional forms of drawing is sometimes revealed by certain metaphors that compare this kind of drawing with less controversial expressions of art and ideas. In his Pedagogical Sketchbook, Paul Klee introduces the captivating image of drawing as "An active line wandering aimlessly, without any goal"3. In the concluding essay he wrote for Tools of the Imagination, edited by Susan Piedmont-Palladino, William J. Mitchell places Klee's wandering against a musical background when he suggests that "Drawing freely is like dancing on paper"4. Architects Le Corbusier and Antoine Predock took this discussion beyond metaphor. Not surprisingly, Le Corbusier has an unambiguous view on the subject. "When you travel and work with visual objects - architecture, painting or sculpture - you use your eyes and draw in such a way as to anchor what you see as thoroughly as possible in your own experience. Once the impression has been recorded, recorded, pencilled in, it remains forever. The camera is a tool for lazy people who use a machine to see for them. To draw yourself, to draw lines, to manage volumes, to organize surfaces... all this is first to look, then to observe, and finally, perhaps, to discover... and that is when inspiration can strike. When you invent or create, your whole being is drawn into action, and that action is what counts."5 |

| Read the full text in issue 1/2014 of Arhitectura Magazine |

| NOTES: 1 I have often started conversations about drawing with this question. This article includes documentation associated with some of the courses co-taught over the years by Professors Stuart Wilson, Gentile Tondino, Ricardo Castro, and Robert Mellin, as well as notes from a conference held at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico, in 2007, and other reflections on drawing. 2 Architect Renzo Piano's design sketches on airplane river bags recovered from countless aircraft have been published in most of the recent monographs dedicated to his work. 3 Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, Faber and Faber, London, 1984, p. 16. 4 Susan Piedmont-Palladino, editor, Tools of the Imagination, Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2007, p. 117. 5 Le Corbusier, Journey to the East, edited and annotated by Ivan Zaknic, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England 2007, p. xiv (The text is quoted by the author in the preface to the second edition, exactly as it was excerpted from Le Corbusier's Creation is a Patient Search ). |

| Why do so many architects still sketch when they travel?1 It's true that there are occasions when our ability to make a quick sketch is convenient - for example, when we find ourselves in environments where photography is forbidden - but our continuing love affair with sketching seems to address desires that are not satisfied by the digital versatility of the portable cameras, tablets and smartphones in our pockets and handbags.We sketch on watercolour blocks and in simple sketchbooks, on napkins in bars and on tablecloths in restaurants; we sketch on airsickness bags2 retrieved from the seat pocket in front of us, on the inside of empty cigarette packs, on the backs of envelopes and business cards, and yes, we even sketch on our smartphones and tablets. We keep journals that document our travels with thoughtful reflections and crisp pencil drawings and we fill notebooks where train schedules and e-mail addresses share the pages with gestural pen and ink sketches of a house by Horia Creangă or an apartment block by Tiberiu Niga. Making these drawings takes time; some are completed in five minutes, others take longer. Short or long, the process defines a relationship with a place that is usually not possible with other forms of documentation - like tablets and most cameras - that literally come between the observer and the subject. The rituals associated with sketching add structure too our encounters with environments that interest us. The drawings that we produce record not only what we saw but also what we were thinking and what we learned. They are not just postcard; they are evidence of our curiosity and our attempts to understand the ideas that shape our world. Our faith in the value of traditional forms of sketching is sometimes revealed in metaphors that compare this kind of drawing to less controversial expressions of art and ideas. In Pedagogical Sketchbook, Paul Klee introduces the compelling image of a drawing as "An active line on a walk, moving freely, without goal"3. In the concluding essay that he wrote for Tools of the Imagination, edited by Susan Piedmont-Palladino, William J. Mitchell animates Klee's walk with music when he suggests that "Drawing with a free hand is like dancing on paper"4. Architects Le Corbusier and Antoine Predock take the discussion beyond the metaphor. Le Corbusier is, not surprisingly, unambiguous on the subject. "When one travels and works with visual things - architecture, painting or sculpture - one uses one's eyes and draws, so as to fix deep down in one's experience what is seen. Once the impression has been recorded by the pencil, it stays for good, entered, registered, inscribed. The camera is a tool for idlers, who use a machine to do their seeing for them. To draw oneself, to trace the lines, handle the volumes, organize the surfaces... all this means first to look, and then to observe and finally perhaps to discover... and it is then that inspiration may come. Inventing, creating, one's whole being is drawn into action, and it is this action which counts."5 |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| NOTES: 1 I often start conversation about drawing whith this question. This article includes material associated with courses co-taught over the years with Professors Stuart Wilson, Gentile Tondino, Ricardo Castro and Robert Mellin, as well as notes from a conference presentation at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Mexico, in 2007, and other reflection on drawing. 2 Architect Renzo Piano's design sketches on the airsickness bags of numerous airlines have been published in most of the recent monographs on his work. 3 Paul Klee, Pedagogical Sketchbook, Faber and Faber, London, 1984, p. 16. 4 Susan Piedmont-Palladino, editor, Tools of the Imagination, Princeton Architectural Press, New York 2007, p 117. 5 Le Corbusier, Journey to the East, edited and annotated by Ivan Zaknic, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England 2007, p. xiv (The text is cited by the editor in the Preface to the Second Edition as having been drawn from Le Corbusier's earlier book Creation is a Patient Search). |