Desenul de arhitectură, liber și angajat

The Architectural Drawing, Free and Engaged

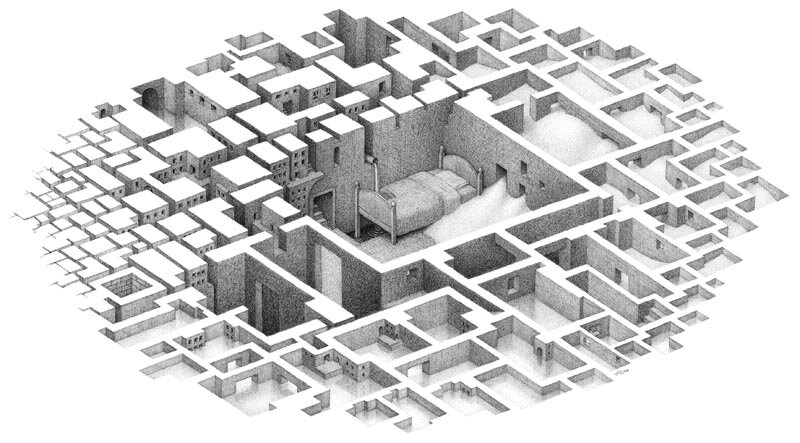

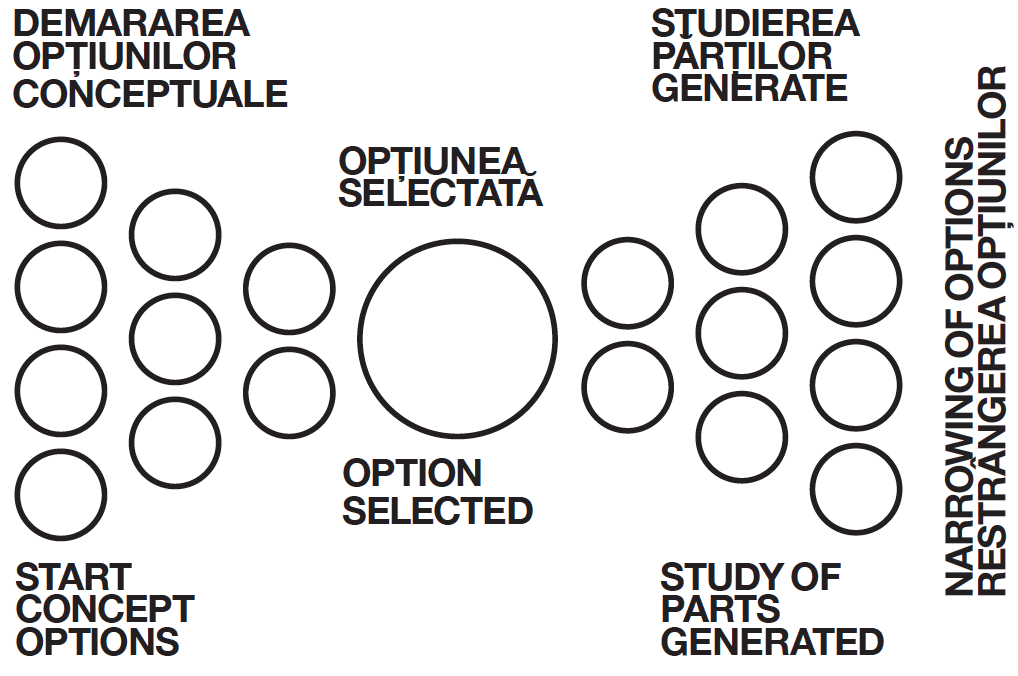

| Multi-arhitectura, ca biodiversitatea

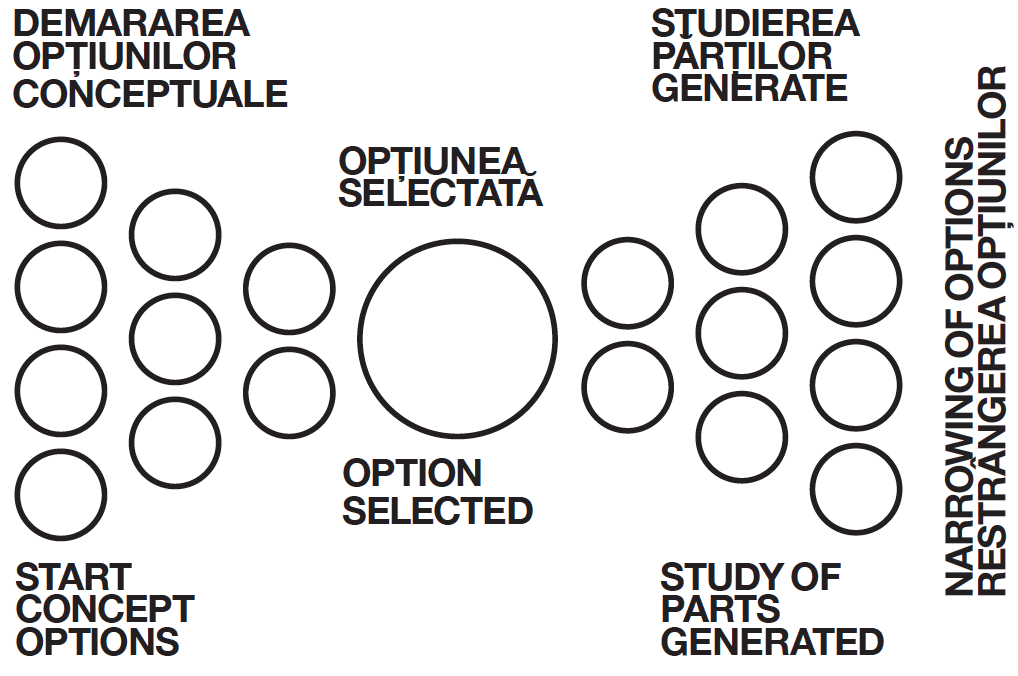

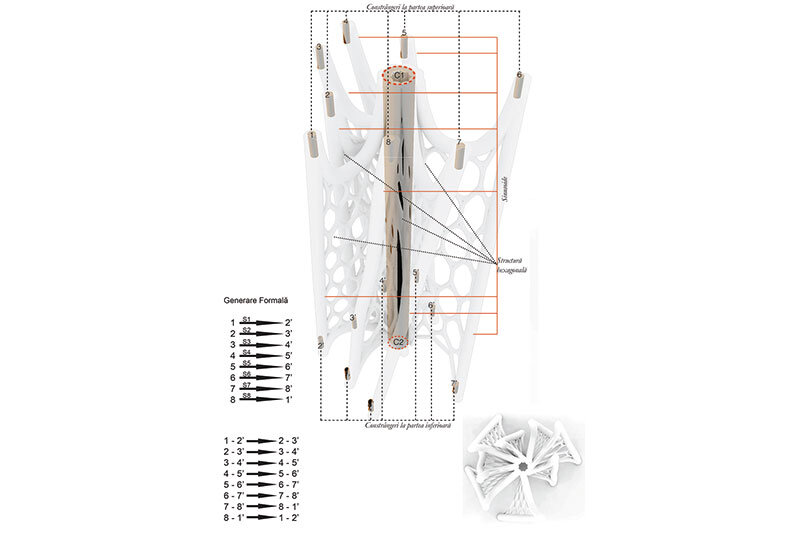

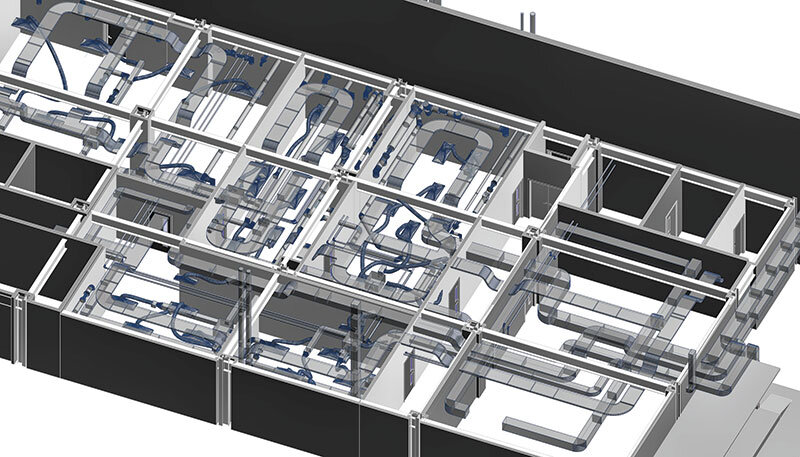

Toată lumea știe că azi nu-ți mai trebuie talent la desen ca să fii arhitect. Păi, nu face azi toată lumea modelare 3D? Toată lumea știe că bunul gust, simțul formelor, al culorilor, al proporțiilor… se învață. Și nimeni nu vrea să știe exact cum le învață cel talentat și cum se prind de cel modest. Nici nu contează, pentru că toată lumea știe că există arhitecți și arhitecți buni, iar statutul arhitecturii s-a deschis cu atâta generozitate încât îi încape pe toți. Probabil că declinul desenului frumos a început odată cu cel al ornamentului, totuși Loos i-a rezervat un destin mai îngăduitor. „Arhitectul cotat, asaltat de clienți și premiat la concursuri nu e cel care știe cel mai bine să construiască, ci acela ale cărui proiecte se prezintă cel mai bine pe hârtie. Or, cel mai bun desenator poate fi un arhitect slab, cel mai bun arhitect un desenator slab. Vechii maeștri se foloseau de desen ca de un limbaj, pentru a se adresa constructorilor.” A dat el liber la desen, dar sigur s-a gândit, în cel mai rău caz, la nemții educați în școlile lor de meserii. Dovadă că, la scurt timp, a apărut și cea mai strălucită confirmare a adevărului lui Loos: genialul Gropius, arhitect sofisticat și inventiv, dar realist și… cu mână de lemn. E adevărat însă că Gropius nu-și considera handicapul o virtute și că i-a angajat la Bauhaus pe cei mai interesanți plasticieni ai vremii. (Asta ar trebui să știe studenții cu mână de lemn care se cred Gropius, precum corijenții la română, bucuroși că se compară cu Eminescu.) Așadar, după cinci secole de parteneriat armonios între arhitectură și desen - asistentul ei devotat, sensibil și frumos - a urmat un secol de relații din ce în ce mai reci. Azi, vechea și nobila artă a desenului a rămas doar un hobby ales al vechilor generații de talentați. Amenințat de tehnicile numerice și fotorealiste, desenul de mână face eforturi să se reinventeze, pentru a-și mai găsi un loc în viața arhitecturii - până când va mai veni odată, poate, și vremea lui. Astfel, pentru că însuși Loos l-a îngăduit atunci când are rol utilitarist, mai întâlnim desenul ca vehicul de comunicare pe note de șantier și în agendele arhitecților. S-ar putea numi schițe de comunicare și sunt frecvente în momentele post-creație, când arhitectului îi e clar ce vrea și trebuie să se facă înțeles de alții. Ele circulă pe parcursul proiectării și al execuției. Nu necesită talent de desenator, ci doar o îndemânare care se dobândește. A-ți folosi mâna și creionul pentru a schița repede o secțiune, un detaliu de plan, o perspectivuță dintr-un unghi anume sau a explica în axonometrie o îmbinare, în loc să scoți laptopul… e o chestiune de eficiență. Și totuși, poate, e și o probă de eleganță. Amintește de vremurile de după prea-vechii meșteri, din timpul celor cinci secole de maeștri, când arhitectul era recunoscut de toată lumea ca artist. Și ce, era așa rău? Nu era rău, dar așa a fost să se întâmple, ca la revoluție. În al șaselea secol, arhitectura n-a evaluat realist situația, cum nici contemporanii ei, Wilhelm al II-lea, Franz Joseph și Nicolae al Rusiei. Față cu reacțiunea, nici ea n-a cedat la timp, ci, curtată de industrializare și cultura de mase, a continuat să se țină mândră și să-și apere titlul de noblețe moștenit de generații. În timp ce inginerii înălțau zgârie nori de capul lor, studenții și arhitecții își petreceau viața producând splendide desene artistice după monumentele trecutului. Ca urmare, acuzată de autism, elitism și anacronism, revoluționarii au măturat-o ca și pe împărați și i-au retras titlul nobiliar de artă. Ca să supraviețuiască, ani mulți a trebuit să se subordoneze noii politici și să asculte de funcțiune. S-a pasteurizat. Și pentru că n-a putut uita suferințele prin care a trecut, curtată azi din nou de aspectele anestetice ale realității dure, a acceptat prompt schimbarea de paradigmă. Și a căpătat multiple înfățișări noi, lăsându-se fecundată de către înaltele politici - energetice, sociale, ecologice, tehnologice, culturale, ale democrației, sustenabilității, urbanității, conurbanității și extraurbanității, ale regionalizării, mobilității, economiei și câte altele. Vechiul ei statut îndrăgit de arhitectură ca artă nu s-a diluat, ci ea le-a preluat discret, le-a înglobat și subordonat estetic. A apărut însă și un nou statut al arhitecturii, în care s-a făcut loc și altor forme de arhitectură integrată, multi, inter și transdisciplinară. Pentru că nici realitatea în care trăim nu e împărțită în discipline. În aceste forme probabil că-și află cel mai bine locul reprezentările diagramatice și graficele, adică formele tehnice, lipsite de scară, iconice, ale desenului de cercetare (științifică). Sunt modelări simbolice și pot fi executate de mână sau de calculator, fără să aibă nimic de pierdut sau de câștigat. De fapt, arată mai bine pe calculator. Prin ele se exprimă latura de cercetător a arhitectului capabil de efort științific. Dar nu sunt doar rezultat al rațiunii, al puterii lui de analiză și judecată multicriterială, ci poartă în ele mult, mult din draga lui conștiință a responsabilității față de omenire. Cum s-o reprezinți într-un desen de mână, despre o casă? Una peste alta, partenerul favorit al arhitecturii de orice fel - tradițională sau integrată - este astăzi calculatorul. El îi desenează impecabil tot ce vrea. În arhitectura tradițională, a început prin a înlocui laborioasa și imperfecta muncă de redactare de mână, adică pe desenatoarea tehnică din secolul al XX-lea, cum ar fi. Din acea vreme, a începuturilor colaborării, provine sintagma proiectare asistată de calculator. Între timp însă, asistentul a promovat spectaculos. Viziunilor indistincte ale arhitectului, el le conferă pe dată imagini clare și precise, colorate și texturate, contextualizate și populate, din câte unghiuri poftește dumnealui. Și mai generează și alte „viziuni” - câte i se cer. Forța generatoare de forme a calculatorului, dar și capacitatea lui de a organiza multicriterialitatea și multe alte capacități merită exploatate.Uneori, această cooperare entuziastă ajunge, de bună-voie, arhitectură dirijată de calculator. Dar în vorbirea curentă se folosește tot vechea sintagmă, autoflatantă, pentru că orice arhitectură își are și ea vanitatea ei. Unora - arhitecți de tip tradițional, dar nu numai - desenul pe calculator li se pare ca atunci când mângâi, cu mănuși, o femeie. Alții însă, tot mai mulți, gustă din plin voluptatea creării de blobi și rizomi din mouse. I se zice biodiversitate. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 1 / 2014 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| Multi-architecture as biodiversity

Everybody knows nowadays that you don’t need any drawing skills in order to be an architect. I mean, doesn’t everybody do 3D modeling these days? Everybody knows that good taste, the sense of forms, the colors and the proportions… can be acquired. Nobody wants to know exactly how the talented one acquires them and how does the less talented one. And it doesn’t even matter, because everybody knows that there are architects and then there are good architects, and the status of architecture has opened so generously that it can accommodate everybody. It is likely that the decline of beautiful drawing began concurrently with that of the ornament. Still, Loos is more understanding with respect to its destiny. “The renowned architect, assailed by customers and recipient of many awards at competitions is not necessarily he who knows best how to build, but he whose projects look best on paper. The best drawer might be a very weak architect and the best architect might be a weak drawer. Old masters used drawing as a language in which to address the builders.” He may have released architects of the obligation to draw well, but he must have had in mind, nevertheless, those Germans educated in their trade schools. Proof is the fact that, shortly afterwards, Loos’ assertion was brilliantly acknowledged: the genius Gropius, a sophisticated, creative architect, who nevertheless was realistic and… couldn’t draw much. It is also true that Gropius did not consider his disability a virtue and hired the most interesting plastic artists of his days to work at Bauhaus. (This fact should be known by those no good at drawing students who believe themselves to be Gropius, much like those pupils who have to resit their Romanian test, for which reason they compare themselves to Eminescu.) Therefore, after five centuries of harmonious partnership between architecture and drawing, its dedicated, sensitive and beautiful partner, there followed a century of increasingly cold relations. Today, the old and noble art of drawing has been relegated to becoming the choice hobby of the old generations of talented architects. Threatened by numerical and photorealistic techniques, hand drawing makes efforts to reinvent itself in order to find a place for itself in the life of architecture, if any. Thus, because Loos itself allowed for it when it had a utilitarian role, we still encounter the drawing as a vehicle of communication on building site notes and in the architects’ agendas. They could also be called communication sketches and are frequent in the post-creation moments, when the architect clearly knows what he wants and needs to be understood by others. They circulate throughout the design and execution phases. You don’t need drawing talent, only a certain address which can be acquired. To use your hand and pencil in order to rapidly draw a section, a plane detail, a perspective from a certain angle or to explain in axonometry a joining instead of taking out your laptop is, after all, a matter of efficiency. And it could be a matter of elegance as well. It calls to mind the five centuries of masters, which followed after the times of the ancient masters, when the architect was known by everyone to be an artist. Was that so bad, after all? It wasn’t bad, it was only meant to be, like the revolution. In the sixth century architecture did not assess the state of play very well, and nor did its contemporaries Wilhelm II, Franz Joseph and Nikolai of Russia. Faced with reaction, it did not give in in time; courted by industrialization and mass culture, it continued to keep its head high and to defend its title inherited generations ago. While the engineers were making skyscrapers according to their own imagination, the students and the architects spent their life producing splendid artistic drawings after the monuments of the past. Consequently, the revolutionaries accused it of autism, elitism and anachronism, and did away with it, much like they did with the emperors, and withdrew its aristocratic title of art subject. In order to survive, it had to obey the new policy for years and to comply with the orders. It was thermally treated. And, because it was unable to forget its suffering, being once more courted by the new, anaesthetic aspects of tough reality, it has promptly accepted the change of paradigm and has acquired new facets, embracing the noble energy, social, technological, cultural, democratic, sustainable, urbanism, con-urbanism and extra-urbanism policies, the policies of regionalization, economics and many more. Its old cherished status of art subject did not dilute; it took all these over subtly, engulfed them and subordinated them to it. However, there appeared a new status of architecture in which room has also been made for other forms of integrated multi, inter and transdisciplinary architecture. Because the reality in which we live is not divided into disciplines either. These forms probably best accommodate diagrammatic representations and charts, i.e. the technical, scaleless, iconic forms of (scientific) research drawings. This is symbolic modelling and can be handmade or computer made, without it gaining or losing anything thereby. In fact, it looks better on the computer. They express the researcher side of the architect who is capable of a scientific effort. But they aren’t a mere result of his reason, power of analysis and multi-criteria judgment; they also carry his immense conscience of his responsibility towards humanity. How can one, then, depict that in a hand drawing about a house? All in all, the favourite partner of architecture of any kind, traditional or integrated, is nowadays the computer. It impeccably draws for it anything it wants. In the realm of traditional architecture, it began by replacing the laborious, imperfect work of hand drawers, i.e. of the technical drawer dating from the XXth century, as it were. It is in those days, when this collaboration started, that the phrase computer-aided design originated. In the meantime, the aid has known a spectacular evolution. It has turned the unclear visions of the architect into clear and precise images, coloured and textured, contextualized and peopled, from as many angles as the architect wants. It is also capable of generating more other innumerable visions. Its form-generating force, as well as its capacity to organize multi-criteriality and many other capacities deserve to be exploited. Sometimes, this enthusiastic cooperation willingly becomes computer-aided architecture. Still, the old, self-flattering phrase continues to be used, because any architecture has its vanity. To some - traditional architects, but not only - computer drawing is very much like caressing a woman with the gloves on. However, others are increasingly enthralled with the mouse-created blobs and rhizomes. It is called biodiversity. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

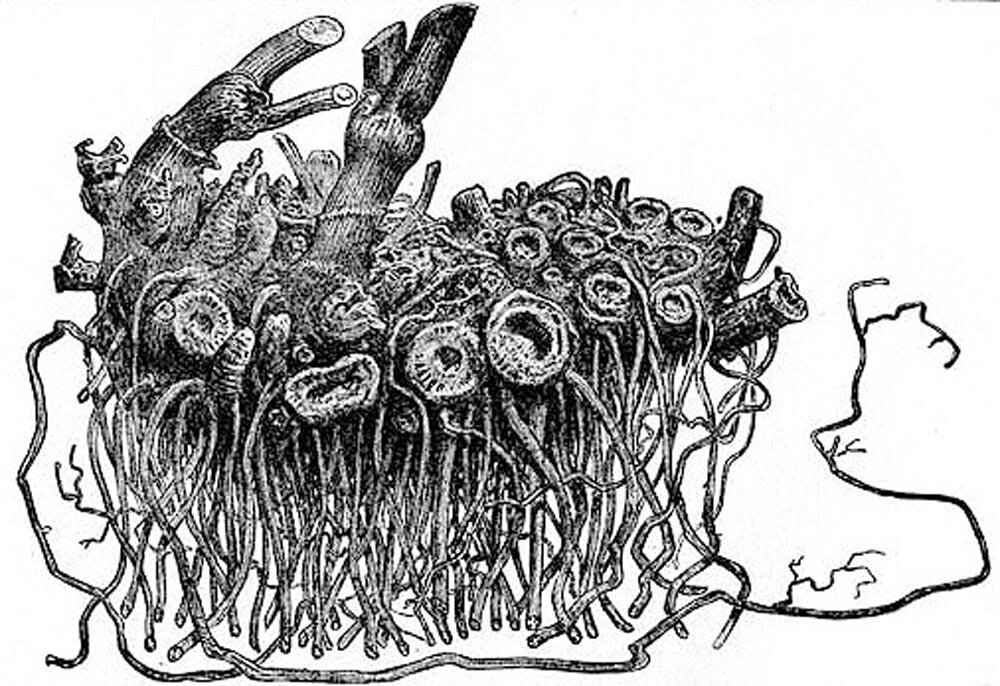

Rozom de cimicifuga racemosa

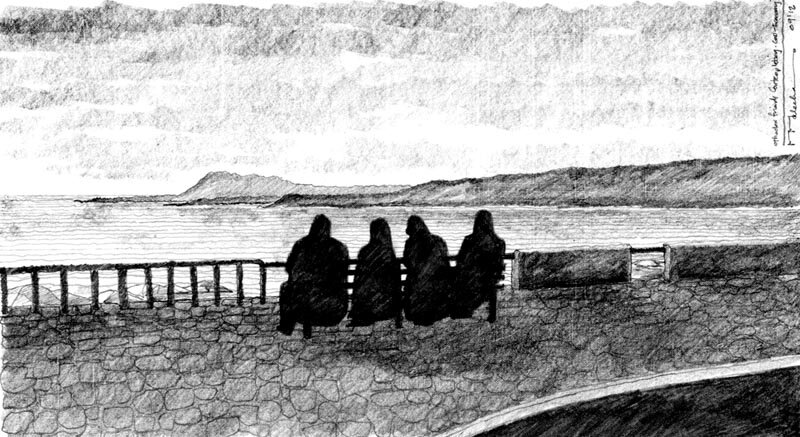

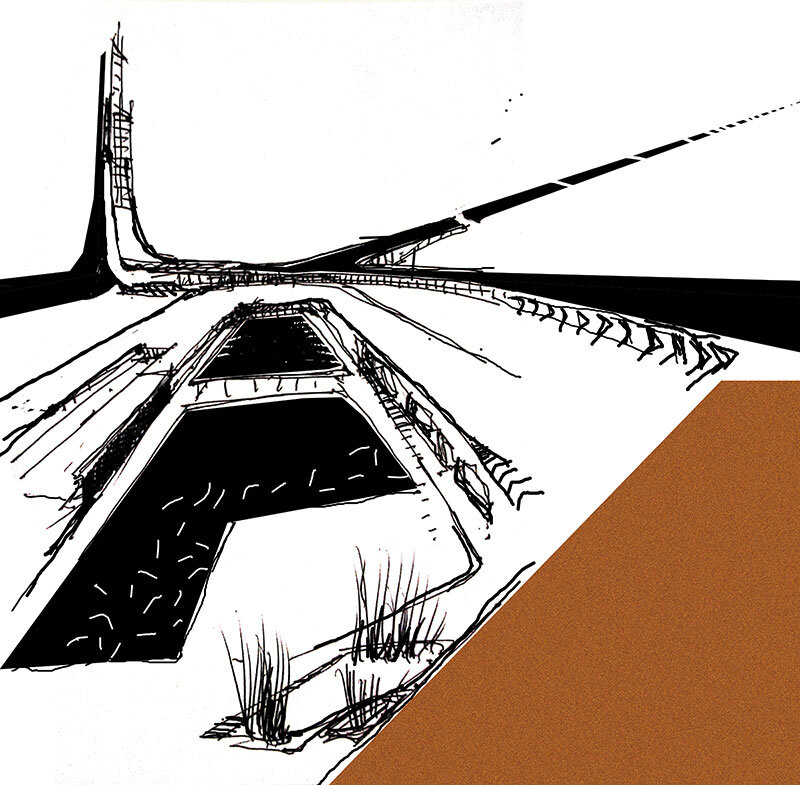

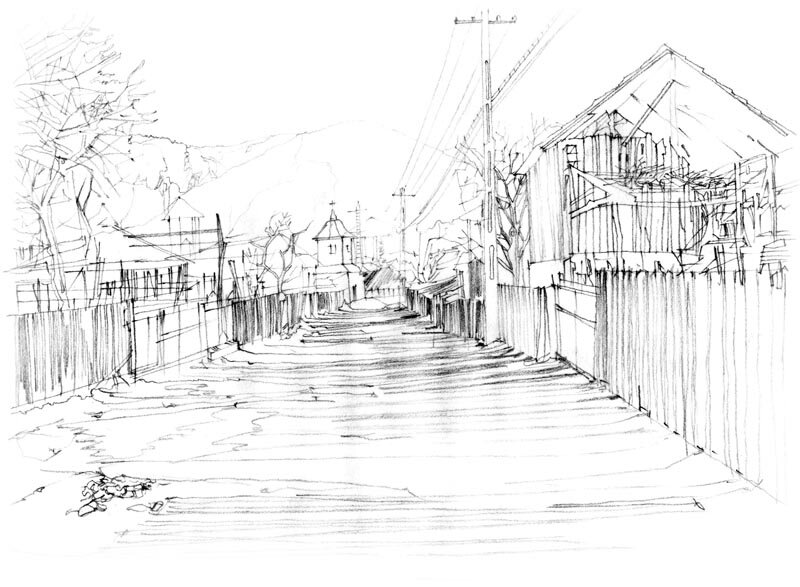

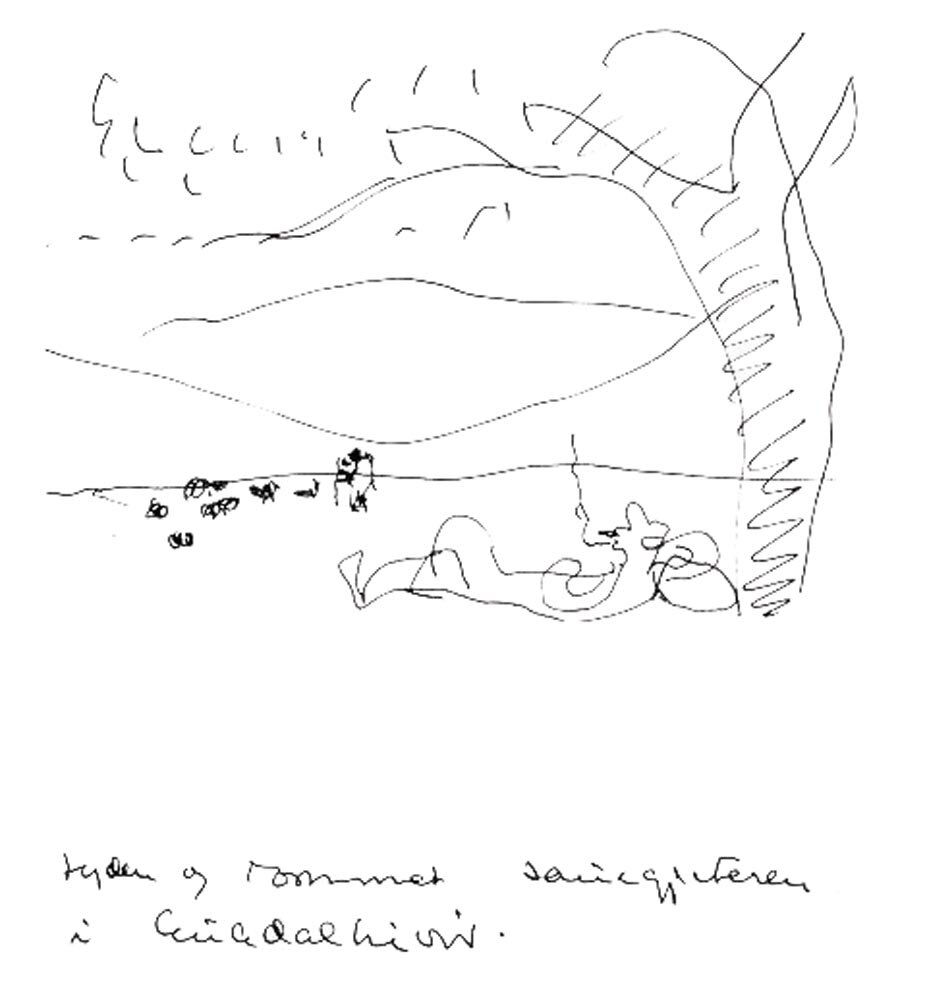

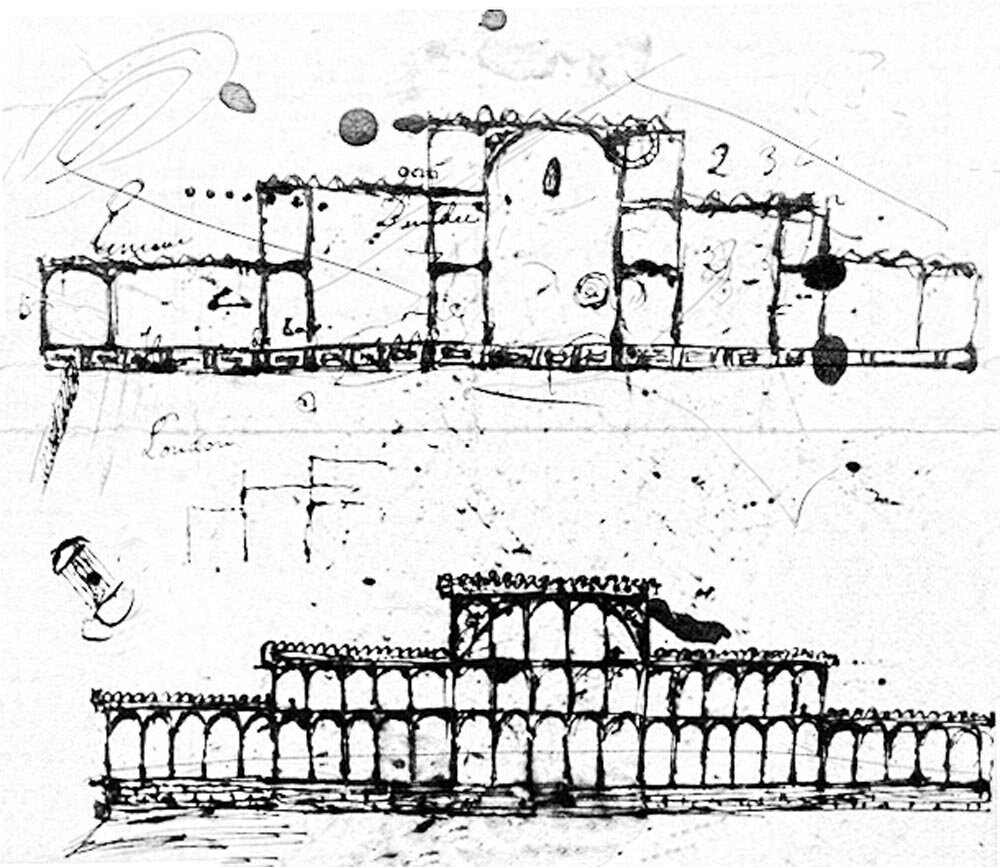

Schiță de Sverre Fehn:

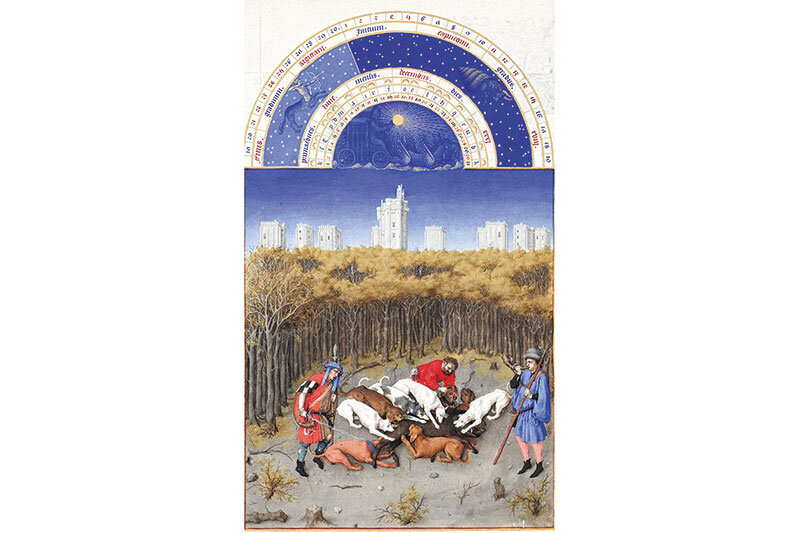

Într-o zi, în Maroc, în 1951: „Construcțiile realizate de animale sunt raționale: precise și imuabile, sunt întotdeauna la fel, zi de zi și an de an… Modul de a gândi al omului nu e riguros, rațional și logic; el înțelege glumele, minciunile, capriciile iraționale. Dacă arhitectura ar fi perfect rațională, ar înseamna că oamenii ar fi devenit animale” (Sverre Fehn)

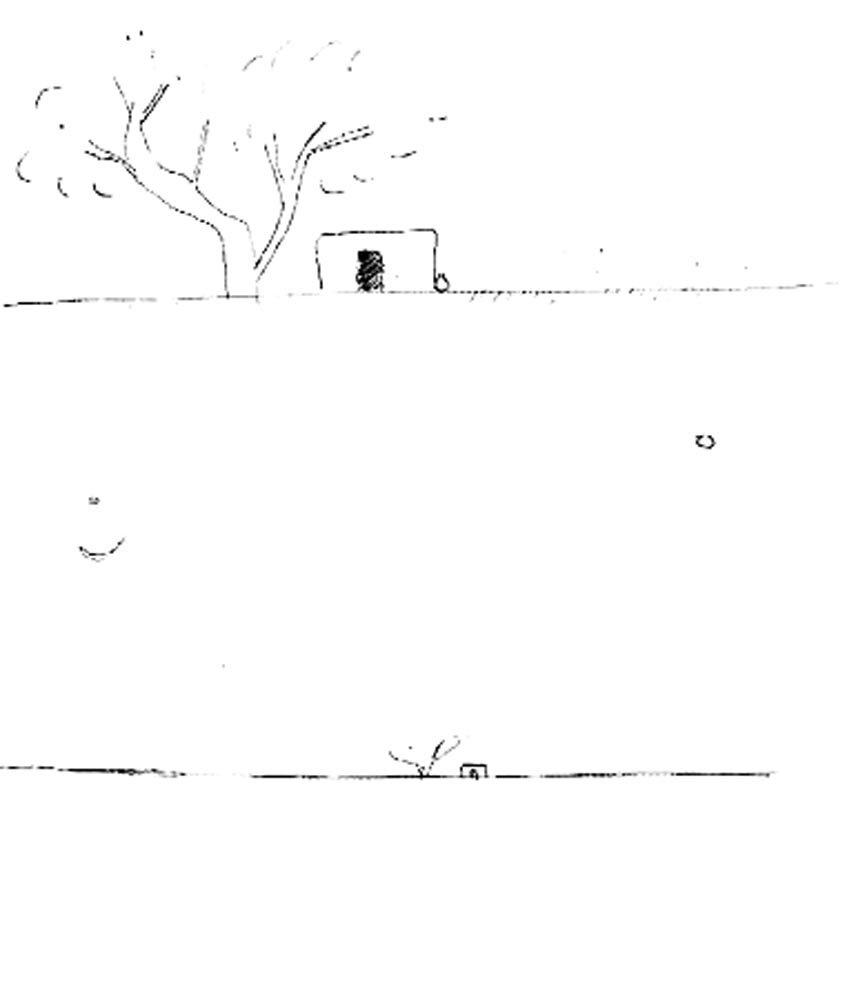

Schiță de Sverre Fehn: The Pattern of Thought este titlul unei cărți de Per Olaf Fjeld despre Sverre Fehn.

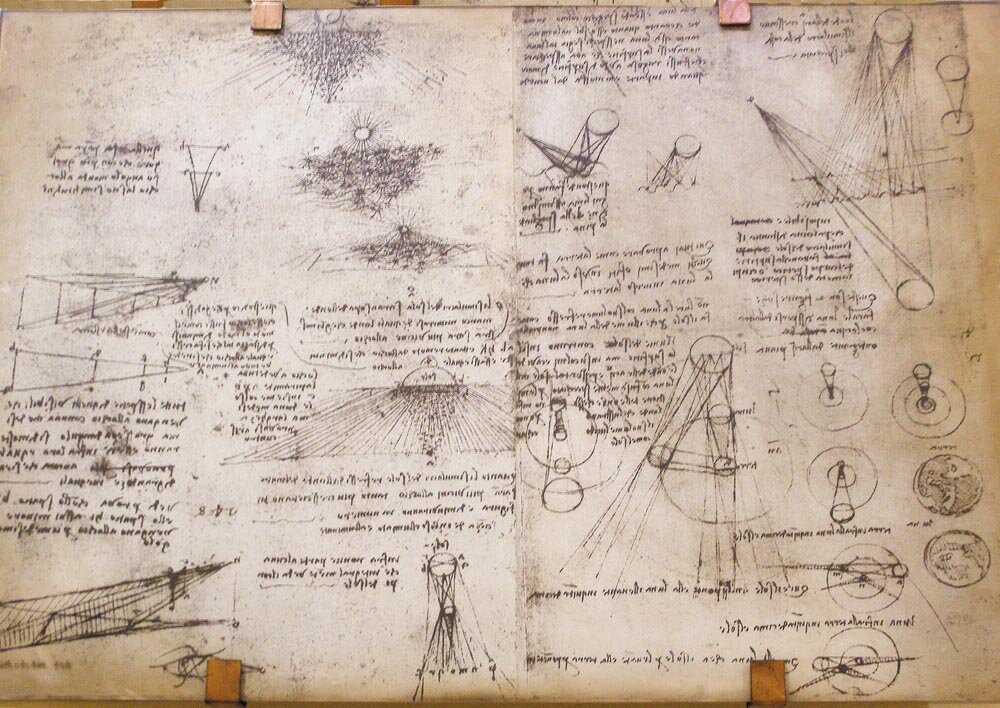

Schiță de Joseph Praxton: pe o bucată de sugativă, într-o zi, la Londra, în 1851, în timpul unei ședințe a comitetului de organizare a expoziției mondiale

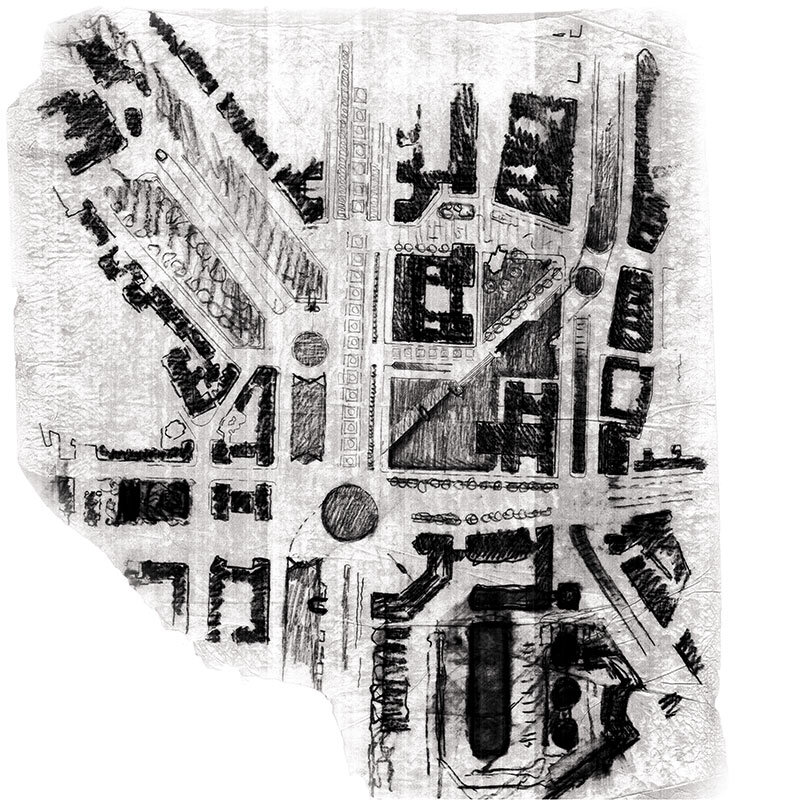

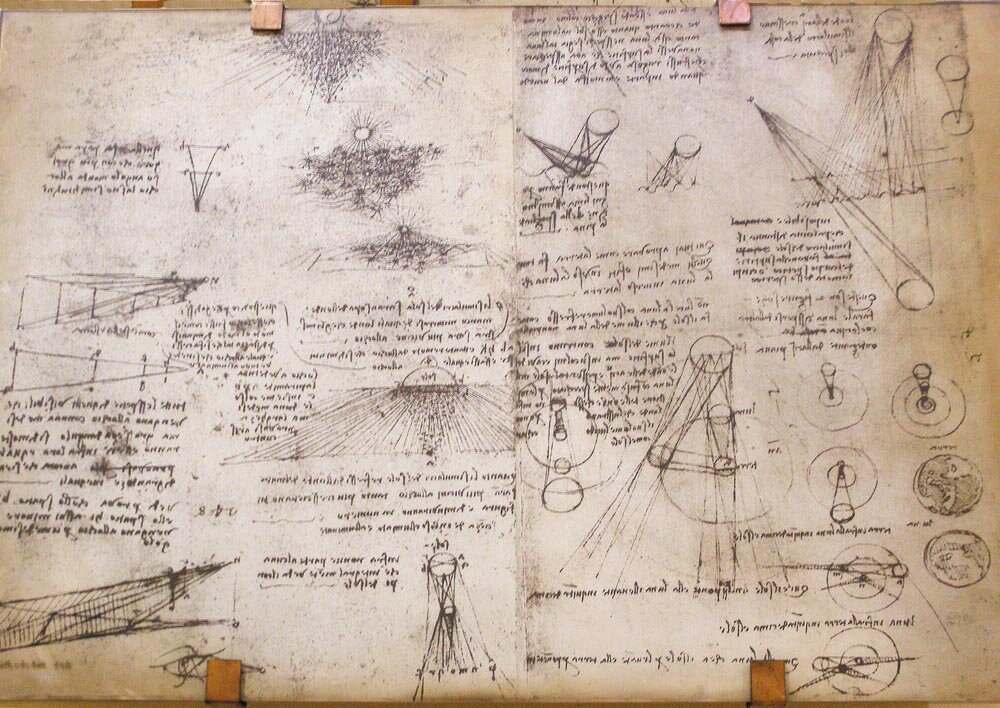

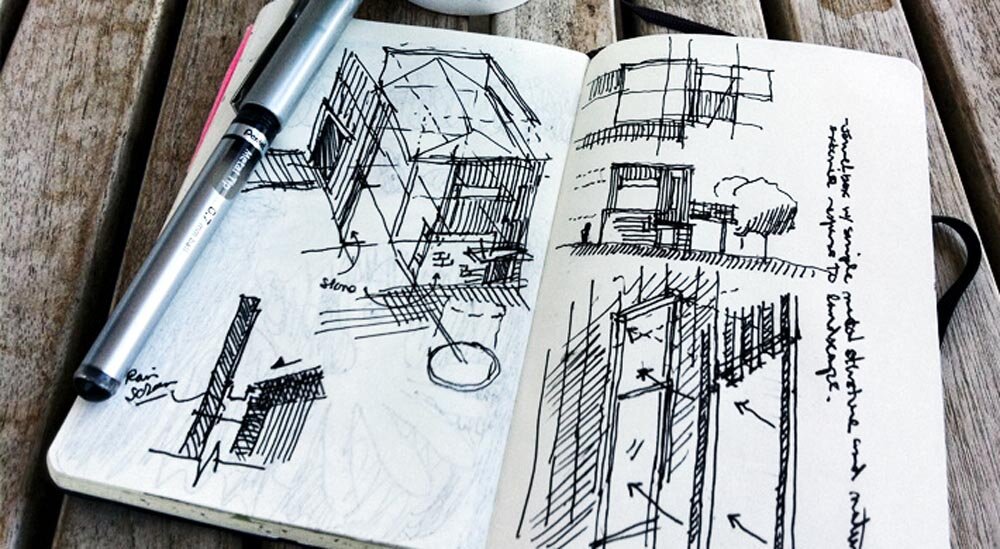

Agendă de arhitect