Unde s-a întâmplat? Cum s-a întâmplat? Reflecții asupra reconstrucției nucleelor istorice ale orașelor distruse în urma cutremurului din 2016 din Italia centrală

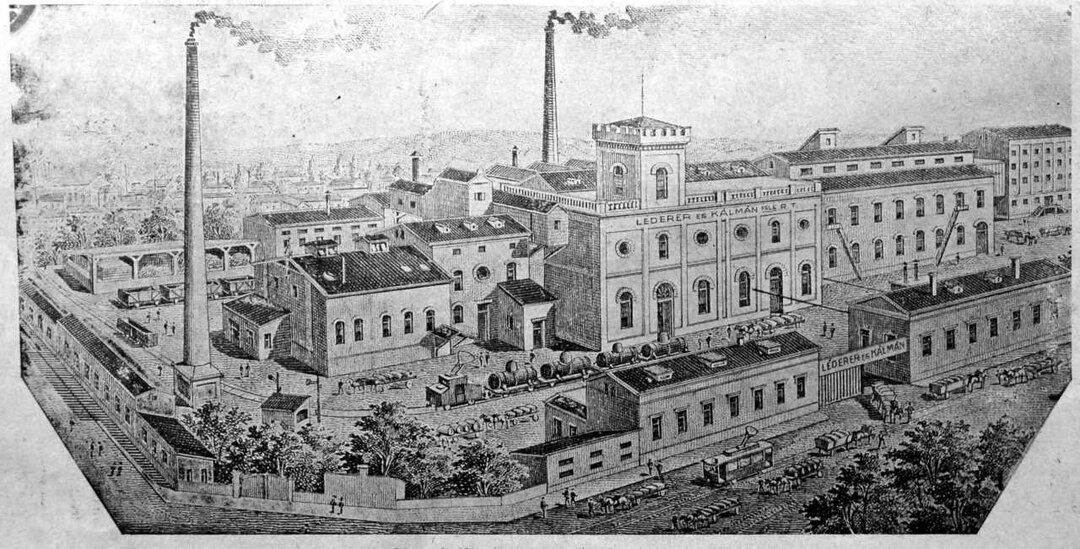

Fig 6: Reamplasarea satului Chiavano (Cascia) după cutremurul din 1979 /

The re-location of the village of Chiavano (Cascia) after the 1979 earthquake

UNDE S-A ÎNTÂMPLAT?

CUM S-A ÎNTÂMPLAT?

REFLECȚII ASUPRA RECONSTRUCȚIEI

NUCLEELOR ISTORICE

ALE ORAȘELOR

DISTRUSE ÎN URMA CUTREMURULUI

DIN 2016 DIN ITALIA CENTRALĂ

WHERE DID IT HAPPEN? HOW DID IT HAPPEN? REFLECTIONS ON THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE HISTORIC CORES OF TOWNS DESTROYED BY THE 2016 EARTHQUAKE IN CENTRAL ITALY

text: Stefano D’AVINO

Înaintea evenimentului seismic din vara anului 2016, teritoriul Italiei fusese lovit de cel puțin alte șapte cutremure devastatoare în ultima jumătate a secolului trecut: Belice (1968), Friuli (1976), Valnerina (1979), Irpinia și Basilicata (1980), Umbria și Marche (1997), Abruzzo (2009) și Emilia (2012).

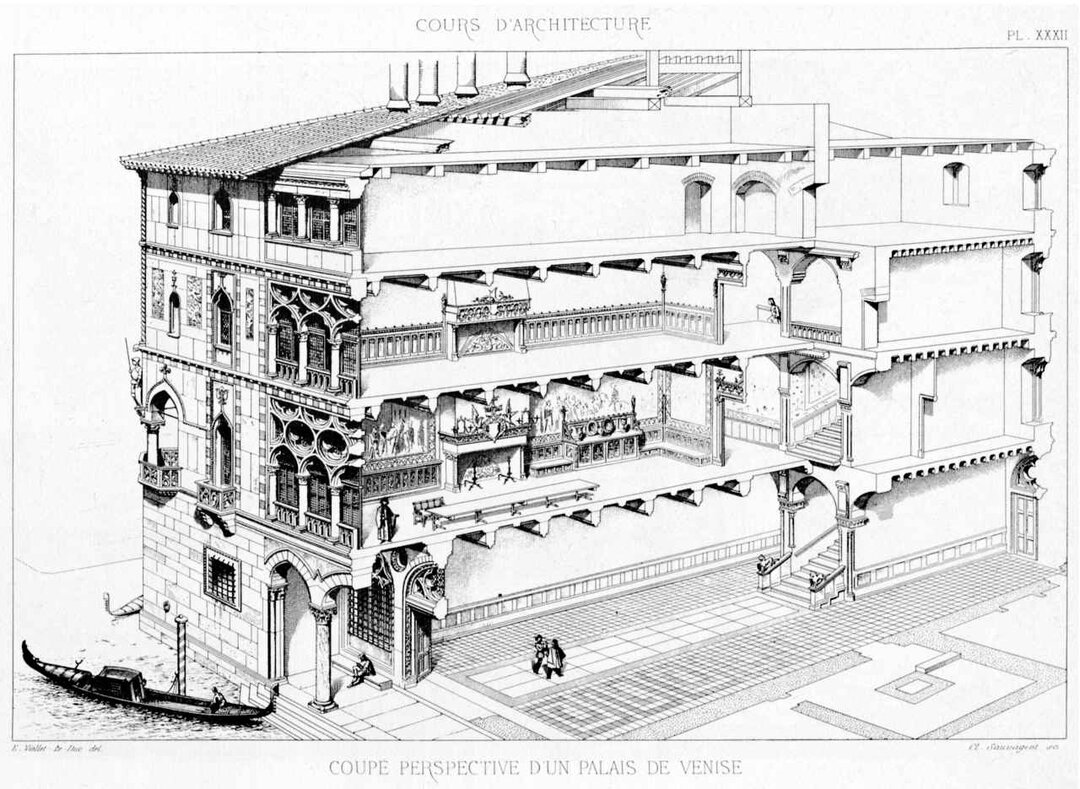

Lucrările de reconstrucție realizate la acel moment nu au avut un caracter unitar, urmând o serie de instrucțiuni diferite, bazate pe fondul de asistență tehnică și expertiză construit de-a lungul anilor și raportate la problemele și obiectivele locale cu care s-au confruntat experții tehnici în fiecare caz în parte. Rezultatele au fost variate - de la exercițiul stilistic desfășurat în Gibelina, cu concursul unor arhitecți și artiști ca Purini, Consagra și Burri (fig. 1), la reconstrucția minuțioasă prin anastiloză a nucleelor istorice din orașele Gemona, Artegna și Venzone (fig. 2a-2b) din regiunea Friuli.

În comparație cu experiențele anterioare, recentul eveniment seismic, unul dintre cele mai ample din istoria seismologiei italiene, reprezintă un fenomen excepțional, având în vedere vasta întindere a teritoriului în cauză, trăsăturile distinctive ale nucleelor istorice din orașele afectate, amalgamul unic de arhitectură și ambient, precum și dimensiunea pagubelor înregistrate. Toate aceste considerente indică necesitatea unor reflecții preliminare înaintea inițierii lucrărilor, referitoare la compromisul dintre conservarea structurilor istorice zonale și nivelul de siguranță impus. Trebuie acordată o atenție deosebită anumitor subiecte (conservare, substituire, reconstrucție) care par să fi rămas pentru o vreme în umbră, fiind în general încadrate în categoria acelor chestiuni (uneori prea îndelung) discutate în decursul secolului trecut.

Un factor fundamental cu o însemnătate deosebită este aparent facila integrare în peisaj a acestor centre populate de mici dimensiuni (fig. 3), generând un tip de unitate a arhitecturii și peisajului care, în virtutea asemănării sale cu un sistem, va constitui întotdeauna obiectul transformărilor determinate de cadrul istoric. Drept urmare, arhitectura unor astfel de situri pare să adăpostească în interiorul său semnele acestor schimbări activate în timp - ilustrând o dinamică a procesului de „adaptare” - ceea ce duce la apariția unei istorii manifeste a metamorfozelor care sfidează, de altfel, prevenția, în măsura în care face parte integrantă din evoluția continuă a întregului sistem, putând fi doar controlată și gestionată.

Fără îndoială, așa cum se întâmplă în toate așezările urbane de mici dimensiuni, patrimoniul construit cu valoare istorică suferă de pe urma unei fragilități structurale atribuite slabei înclinații de a-i recunoaște valoarea ca artefact sau de a-i conferi o dimensiune specific „monumentală”, un neajuns ce periclitează conservarea unui patrimoniu care, mai presus de rolul său de document de istorie și arhitectură, constituie o moștenire de identitate și memorie. Ca atare, primul demers în acest sens pare să fie o documentare conștiincioasă asupra tuturor tehnicilor de construcție și criteriilor de prevenție seismică utilizate de-a lungul secolelor, un efort ce ar contribui considerabil la înțelegerea demersurilor ce trebuie întreprinse în viitor, înaintea următoarelor evenimente catastrofale, pentru a asigura astfel siguranța clădirilor istorice, sprijinind în același timp și conservarea acestora. Cunoașterea tehnicilor tradiționale de construcție devine „un ingredient necesar în elaborarea rapidă a programelor de reconstrucție și restaurare” (Varagnoli, 68).

Subiectul refacerii post-seismice a patrimoniului construit dă naștere unei întrebări inevitabile, referitoare la procedurile de reconstrucție ce urmează a fi aplicate. Există două obiective operaționale ce trebuie luate în calcul: pe de-o parte, iminența reparării rapide a daunelor provocate de cutremurul care a zguduit nu doar structurile arhitectonice, ci însăși conștiința de sine și identitatea populației locale; pe de altă parte, reconstrucția unor porțiuni întinse de țesut istoric fragil care, suprapuse în timp, alcătuiesc o formă stratificată de memorie pierdută, cel puțin în parte, pentru totdeauna. Un astfel de efort, indiferent de gradul înalt de certificare al metodologiilor care au contribuit la îndeplinirea sarcinii, trebuie să aibă în vedere, în mod obligatoriu, natura unică a artefactelor materiale: fiecare merită să fie analizat și „ascultat” în parte.

În materie de memorie urbană, trebuie să se depună eforturi în direcția sprijinirii procesului de reconstrucție bazat pe repararea, renovarea și restaurarea elementelor salvate după cutremur, chiar și în cazurile în care nu mai există decât configurația urbană (piețe publice, rețele stradale și de transport, planuri de locuințe etc.), evitând, totodată, abordări axate pe demolarea completă și reconstrucția de la zero, cu riscurile inerente legate de pierderea permanentă a componentelor de identitate și memorie.

Prior to the seismic event that occurred in the Summer of 2016, Italian territory had been struck by at least seven other disastrous earthquakes in the course of the last half century: Belice (1968), Friuli (1976), Valnerina (1979), Irpinia and Basilicata (1980), Umbria and the Marche (1997), Abruzzo (2009) and Emilia (2012).

The reconstruction work done on those occasions was not uniform, but rather followed a variety of different guidelines, based on the storehouse of technical support and knowledge that had accumulated over the years, as well as the local problems and aims presented to the technical experts in each instance. The results ranged from the stylistic exercise carried out in Gibellina, with contributions from architects and artists, including Purini, Consagra and Burri (fig. 1), to the painstaking reconstruction by anastylosis of the historic cores of the towns of Gemona, Artegna and Venzone (fig. 2a-2b) in the Friuli region.

Compared to previous experiences, the recent seismic event, one of the most extensive in the history of Italian seismology, constitutes an exceptional occurrence, given the vast expanse of territory involved, the distinguishing characteristics of the historic cores of the towns struck, the unique amalgamation of their architecture and the surrounding environments, as well as the magnitude of the damage registered. All these considerations point to the need for preliminary reflections, before any work is undertaken, on the give and take between preservation of the historic underpinnings of the areas and the level of safety required. Attention must once again be focussed on topics (preservation, replacement, reconstruction) that for a time appeared to have receded into the background, having essentially been classified among those issues discussed (at times at too much length) during the last century.

An underlying factor of particular significance is the readily apparent integration of these small-scale population centres with the backdrops of their landscapes (fig. 3), giving rise to a unity of architecture and surroundings that, given its resemblance to a system, shall always be subject to the transformations engendered by history, with the result that the architecture of such sites seems to harbour within itself the signs of these changes, or dynamics of ‘adaptation’, triggered over time, until they form what amounts a visible history of mutations that, for that matter, defy prevention, inasmuch as they are part and parcel of the ongoing evolution of the entire system, but can only be disciplined and governed.

There is no question that this heritage of historic constructions, as occurs in all small-scale urban settings, suffers from an inherent fragility attributable to the scarce propensity to acknowledge its value as an artefact, or to grant it a specifically ‘monumental’ dimension, a failing that places at risk the preservation of a heritage that, above and beyond its role as a record of history and architecture, constitutes a legacy of both identity and memory. As such, the first step to be taken would appear to be a thorough documentation of all the construction techniques and criteria of seismic prevention followed over the centuries, an effort that would contribute greatly in terms of arriving at an understanding of what initiatives should be undertaken in the future, before the next catastrophic events, so as to ensure the safety of historic constructions while favouring their preservation. A knowledge of traditional construction techniques becomes a “necessary ingredient in the rapid formulation of programs of reconstruction and restoration” (Varagnoli, 68).

The topic of the post-seismic recovery of the heritage of historic constructions gives rise to an unavoidable question, and namely the reconstruction procedures to be employed. There are two distinct operating objectives to be considered: on the one hand, the need for rapid repair of the damage done by an earthquake that shattered not only architectonic structures but the very self-awareness and identity of the local populations themselves; on the other, the reconstruction of extensive portions of a delicate historic fabric that, having cumulated over the centuries, constitutes a form of stratified memory that, at least in part, has been lost forever. Such an effort, no matter how proven the methodologies brought to the task, must necessarily take into consideration the unique nature of the material artefacts, each of which deserves to be attended to, to be ‘heard’, in its own right. In terms of urban memory, an effort should be made to favour a process of reconstruction based on the repair, recovery and restoration of what has been saved from the earthquake, even in cases where this is nothing more than the urban layout (piazzas, routes of streets and routes, formats of homes etc.), while avoiding, on the other hand, approaches keyed on complete demolition and reconstruction from scratch, with the attendant risks of further and permanent loss of elements of identity and memory.

Înlocuirea elementelor absente

Cutremurul a distrus „legătura dintre idee și materie, dând naștere unei situații în care permanenta ecuație dintre cele două tensiuni s-a autoanulat, în sensul că o stare de ruină totală nu mai poate comunica nimic” (Dezzi Bardeschi, 4).

Ce este de făcut? Evoluția conceptuală a ultimelor câteva decenii a generat apariția unei serii de abordări operaționale diferite, de la înlocuirea din considerente filologice, bazată pe implementarea repetată a unui cod lingvistic tradițional, la practicarea unei funcțiuni de design condiționate de o concepție critică: „Dacă elementele absente constituie o secțiune relevantă a întregului... și având în vedere că ele nu reprezintă un construct monumental în sine... în sensul că nu au statutul de opere de artă, ci restabilesc coordonatele spațiale; și că, tocmai pentru că nu reprezintă niște opere de artă, acestea nu subminează calitatea artistică a mediului în care sunt inserate cu scopul de a servi drept configurații spațiale clasificate generic (...); dacă astfel de condiții sunt viabile, elementele care lipsesc pot fi reconstituite pentru a reface sistemul spațial inițial pierdut” (Brandi, 72). Bineînțeles, trebuie avută în vedere expresivitatea componentelor absente prin acceptarea sugestiilor determinate de o analiză conștiincioasă a matricei și a trăsăturilor formale pentru a putea avansa în sincronie cu acele elemente preexistente și în conformitate cu conceptul deja larg răspândit al „minimei intervenții”. De asemenea, eforturile de înlocuire trebuie să respecte echilibrul obținut de arhitectură prin utilizarea unui limbaj „specific”, dar estetic coerent, asigurându-se că extinderile vor fi mereu în plan secund, însă fără efecte negative asupra unității figurative ce urmează a fi refăcute.

Este extrem de importantă păstrarea valorii documentării istorice în timpul desfășurării lucrărilor de restaurare deoarece aceasta reprezintă, efectiv, istoria transmisă prin intermediul formei și stratificată în timp, precum și perpetuarea memoriei evenimentului. De fapt, este de la sine înțeles că o operațiune de restaurare ancorată în analiza istorică nu va diminua defel valoarea monumentului ca memorie, chiar dacă presupune reconstrucții parțiale. Așadar, practica restaurării trebuie să țină cont de această abordare, alternativa fiind rezumată astfel: „În locul unui concept bazat exclusiv pe conservare, trebuie să adoptăm o viziune însuflețită de memoria activă, imaginară” (Cacciari, 13).

În plus, problema înlocuirii elementelor absente presupune analizarea relației dintre vechea entitate existentă și inserția modernă. În acest scop, proiectul de restaurare trebuie să stabilească un compromis eficace în raport cu ruinele, facilitând refacerea acestora cu ajutorul materialelor contemporane, în conformitate cu principiul minimei intervenții și în opoziție cu efectuarea unor extinderi cu caracter ireversibil. În practică, proiectarea noii structuri trebuie să cuprindă, în mod imperativ, includerea țesutului vechi. În caz contrar, un limbaj disonant, voit eterogen, va împiedica integrarea segmentelor fragmentate, generând un contrast între vechi și nou, iar semnele designului contemporan se vor suprapune peste limbajul din trecut, ceea ce va face ca eforturile de restaurare să pară doar un pretext.

Reconstrucția nucleelor istorice ale orașelor

În iunie 1981, în urma cutremurului care a afectat puternic localitatea Irpinia pe 20 noiembrie 1980 și la o doi ani de cel care a lovit valea Valnerina în septembrie 1979, Tomas Maldonado, redactorul revistei Casabella, a scris un editorial intitulat: „Earthquake, which reconstruction”, fără niciun semn de întrebare, pentru a sublinia importanța capacității (eminamente tehnice) de a gestiona procesul de reconstrucție: „(...) în acest moment, nu poate fi avansată nicio interpretare sau evaluare critică nouă” (Maldonado, 7). Și totuși, cel puțin în practică, această capacitate nu a fost încă demonstrată, dar a provocat mai multe pagube și a generat, de-a lungul anilor, analize aprofundate și evaluări critice.

Pe lângă efectuarea lucrărilor legitim indispensabile, necesare pentru rezolvarea cerinței de locuire din acel moment, și garantarea condițiilor de siguranță a patrimoniului arhitectonic avariat, este esențial ca discuția să se concentreze asupra reconstruirii în cadrul unei politici culturale elaborate în conformitate cu problema riscului seismic și cu strategiile operaționale utilizate în vederea protejării patrimoniului artistic și istoric.

Acest lucru nu presupune însă ignorarea legăturii solide dintre patrimoniu, protejarea nucleelor istorice ale orașelor și adaptarea lor ulterioară la condițiile dinamice (și variabile) de viață ale societății eterogene contemporane.

În acest sens, Alberto Samonà este de părere că: „Nu se pune problema ca noua arhitectonică și abordare urbanistică să fie o consecință directă a noilor cerințe de construcție [sau reconstrucție] impuse de cutremur (tipuri de structuri, folosirea unor anumite materiale etc.); cu alte cuvinte, contemplarea conceptuală a problemelor legate de căutarea unei noi expresii nu are niciun rost. În schimb, având în vedere aspectele teoretice și operaționale ridicate de evenimentul seismic, trebuie întreprinse eforturi în vederea dezvoltării mai multor direcții complexe de gândire menite să pună în lumină caracteristicile specifice fiecărei zone lovite de cutremur” (Samonà, 10).

Cutremurul a adus în discuție și eventualitatea reexaminării unei teze care părea să nu mai antreneze posibilități de reflecție: opțiunea de a reconstrui așacum era și în locul în care era în perioada post-seism. Indubitabil, o asemenea perspectivă exercită o anumită atracție chiar dacă aduce cu sine un potențial de ambiguitate, în special pentru că există mai multe moduri de interpretare a conceptului „așa cum era”, de la ceea ce ar putea fi considerat o reconstrucție „filologică” la o restaurare simbolică, exclusiv exterioară, cu posibilitatea de a menține formele exterioare, dar cu modificarea interioarelor, chiar în detrimentul particularităților designului și construcției originale care constituie, de fapt, elementele fundamentale ale arhitecturii în ansamblu.

Atunci când vine vorba despre o reconstrucție, este indicată menținerea, pe cât posibil, a elementelor care s-au păstrat din vechea structură pentru a acționa ulterior în cunoștință de cauză și în spiritul unei culturi axate pe considerente arhitectonice pentru a reface clădiri care sunt, în unele cazuri, extrem de vechi, chiar dacă au fost restaurate și au redevenit sigure; în alte cazuri, rezultatul va fi un amalgam actual și condescendent de nou și vechi sau vor fi create clădiri moderne care evocă valori urbane, configurații volumetrice, spațiale și structurale, materiale și culori din trecut.

De fapt, nici măcar reconstrucția orașului Venzone (adesea amintită ca exemplu relevant) nu poate fi considerată un exercițiu în încercarea de a reda cu perfectă acuratețe fondul construit original: „Este o reconstrucție care a păstrat intacte semnele evenimentelor petrecute, evitând să șteargă trauma cutremurului și alegând să lase vederii numeroase cicatrice, unele destul de adânci. Prin urmare, nu totul este așa cum era, având în vedere că, cel puțin în parte, este așa cum a devenit în timpul transformării tumultoase provocate de cutremur și pe parcursul numeroșilor ani ce au urmat, dar și așa cum a fost reconstruit în timpul lucrărilor de restaurare” (Doglioni, 71).

The replacement of what is missing

The earthquake has disrupted “the bond between idea and material, establishing a situation in which the perennial equation between these two tensions has cancelled itself out, in the sense that a state of total ruin no longer communicates anything” (Dezzi Bardeschi, 4).

What should be done? The conceptual evolution of the last few decades has generated a number of different operating approaches: from replacement on a philological basis, founded on the repeated implementation of a traditional linguistic code, to the practice of a design function bound by a critical outlook: “Should what is missing regard a noteworthy portion of the whole… and assuming that the lost elements do not constitute a monumental construct in and of themselves (…) in that they do not comprise a work of art, and yet they restore the spatial coordinates, though, for the very reason that they are not works of art, they do not undermine the artistic quality of the setting, in which they are inserted only to serve as generically qualified spatial outlines (…), if these conditions hold, then the elements that have disappeared may be reconstructed, in order to restore the original spatial array that has been lost” (Brandi, 72). Naturally, consideration must be given to the expressive quality of what was in place previously, taking in the suggestions generated by a thorough analysis of its matrix and formal features, so as to move forward in synch with those pre-existing elements, in keeping with what is by now the widely endorsed concept of ‘minimum intervention’. Replacement efforts must also respect the balances achieved by architecture through the use of a ‘distinctive’ but aesthetically consistent language, ensuring that the addition always plays a secondary role, though without diminishing the figurative unity that is to be restored.

It is vitally important that, while the restoration work is underway, the values of historical documentation be kept in place, representing, as they do, history transmitted by form, and then stratified over time, and that the memory of the event also be kept alive. In fact, it goes without saying that a restoration operation rooted in historical analysis, even if it includes partial reconstructions, shall in no way reduce the value of the monument as memor. And so the practice of restoration must take this approach into account into account, with the alternative being that, “instead of an outlook resting merely on preservation, we should arrive at a vision imbued with an active, imaginative memory” (Cacciari, 13).

The question of replacing what is missing also leads to consideration of the relationship established between the old existing entity and the modern insert. To this end, the restoration project must establish a fruitful give and take with the ruin, facilitating its reformulation, through the use of modern materials, in compliance with the principle of minimum intervention, as opposed to making irreversible additions. In practice, the design of the new must arrive at a vital involvement of the old. Otherwise, a deliberately diverse, dissonant language will impede the integration of the fragmented portion, setting up a contrast between old and new, with the signs of the contemporary design overlapping thenlanguage from the past, so as to make the restoration effort appear to be nothing more than a pretext.

The reconstruction of the historic cores of towns

In June of 1981, in the aftermath of the seismic event that heavily damaged Irpinia on 23 November 1980, and at a remove of two years from the earthquake that struck the Valnerina valley in September of 1979, Tomas Maldonado, editor of the magazine Casabella, wrote an editorial under the title of: ”Earthquake, which reconstruction”, without a question mark, as if to stress the capacity (exquisitely technical) to govern the process of reconstruction: “(…) at this point there is no new interpretation to be advanced, no new critical assessment” (Maldonado, 7). And yet this capacity, at least in practice, has yet to be demonstrated, instead producing further causes for damage while leading, over the years, to in-depth reflection and critical evaluation.

Apart from the admittedly indispensable work needed to meet the need for habitation in the moment, while also guaranteeing the future safety of the damaged architectonic heritage of the past, it is of key importance that the focus of discussion be trained on the question of reconstructing within the framework of a cultural policy formulated with an eye towards seismic risk and the operating strategies to be employed as a result, so as to protect the artistic-historical heritage.

Though this does not mean overlooking the enduring bond between this heritage, the safeguarding of the historic cores of towns and their subsequent adjustment to the changing (and changeable) living conditions of today’s multiform society.

Along these lines, Alberto Samonà holds that, “There is no issue of the new architectonic and urban-planning approach being a direct outgrowth of the new demands posed for construction [or reconstruction] by the earthquake (types of structures, the use of certain materials etc…); in other words, there is no point in abstract contemplation of the problems of new expression. Instead, in considering both the theoretical and operational issues raised by the seismic event, an effort should be made exploit the occasion for the development of more all-encompassing lines of thinking able to bring forth the specific characteristics of each area struck by the earthquake” (Samonà, 10).

The earthquake also posited the eventuality of revising a tenet that no longer appeared to give cause for further reflection: whether to rebuild as it was and where it was in the wake of a seismic event. Such an outlook undoubtedly holds a certain allure, though it also comes with a certain potential for ambiguity, in particular because there is more than one way of interpreting the concept of ‘as it was’, ranging from what can be considered a ‘philological’ reconstruction to a purely external, symbolic restoration, with the possibility of preserving the external forms but modifying the interior, even at the expense of features of the original design and construction which, in truth, constitute fundamental elements of the architecture as a whole.

In approaching a reconstruction, it is best to maintain as much as possible of the surviving traces of the old structure and then proceed with an awareness and culture keyed on considerations of design, so as to reprise buildings that, in some cases, shall be thoroughly old, even if they have been restored and rendered secure, while, in other cases, the result will be a new, respectful amalgam of the old and new, and in still other cases, the buildings shall be modern but evocative of urban values, volumetric, spatial and structural layouts, materials and colours of the past.

For that matter, not even the reconstruction of Venzone (often pointed to as an apt paradigm) can be considered an exercise in the restoration of something precisely similar to what came before: “It is a reconstruction that left intact the signs of what had occurred, failing to cancel all the trauma of the earthquake while leaving scars, some of them quite intense. All is not, therefore, as it was, seeing that, at least in part, it is as it became during the tormented transformation wrought by the earthquake and during the many years after that, in addition to being as it was reconstructed while restoration work was underway” (Doglioni, 71).

În plus, apar și alte dificultăți legate de scara pagubelor cauzate de seism: insecuritatea geologică a zonelor afectate, lipsa de siguranță a structurilor istorice, în ceea ce privește configurația urbană și cea a construcțiilor individuale, precum și depopularea zonelor muntoase în cauză, un fenomen care are loc de multe decenii.

Nu încape îndoială că proiectele de restaurare similară trebuie abordate la scări diferite, de la clădiri individuale la centre urbane populate sau peisaje.

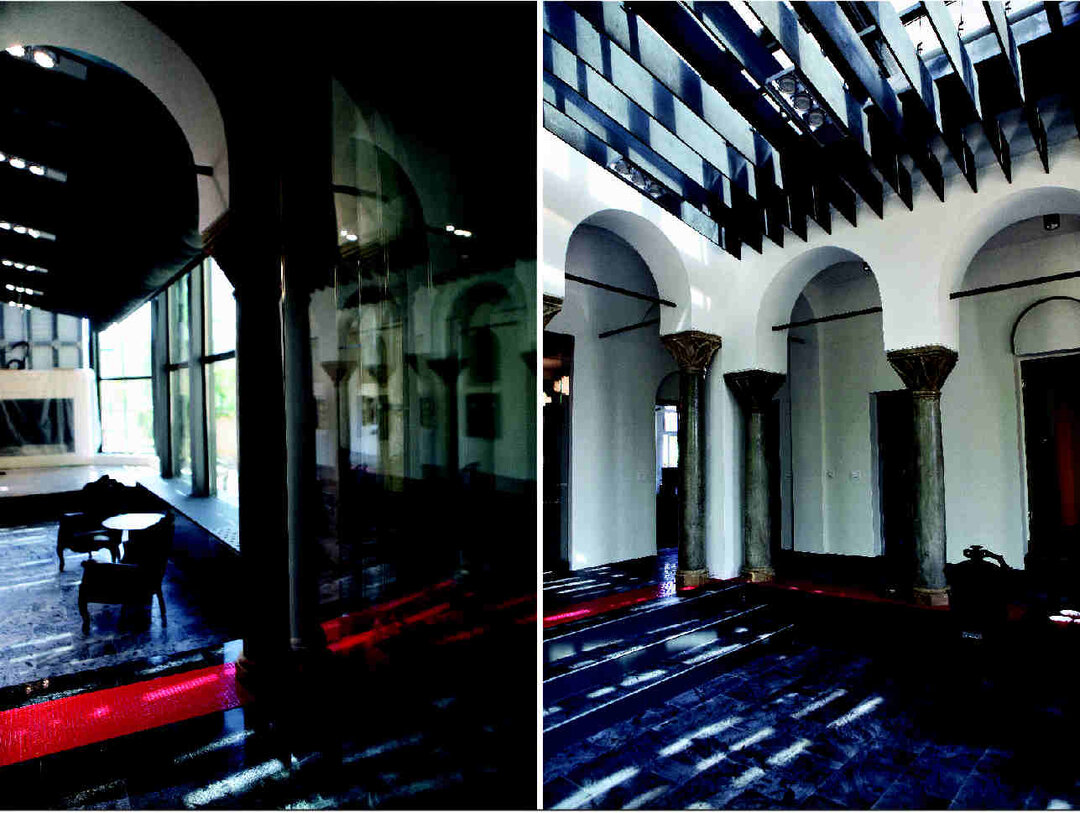

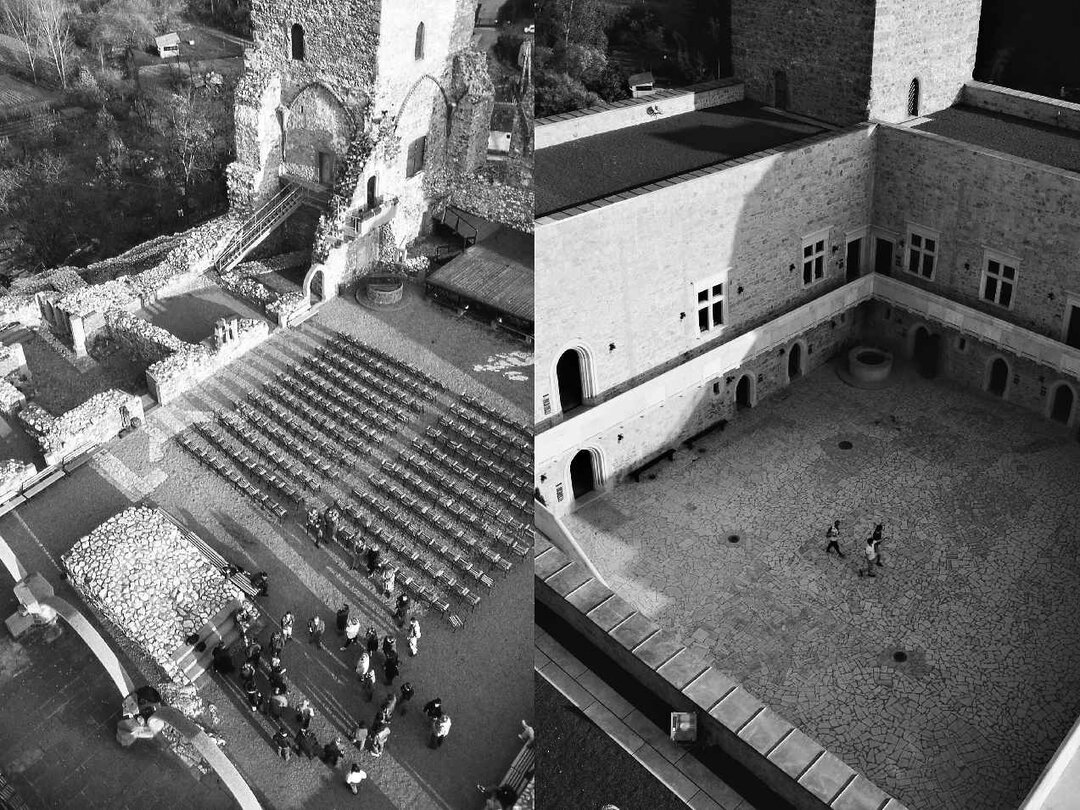

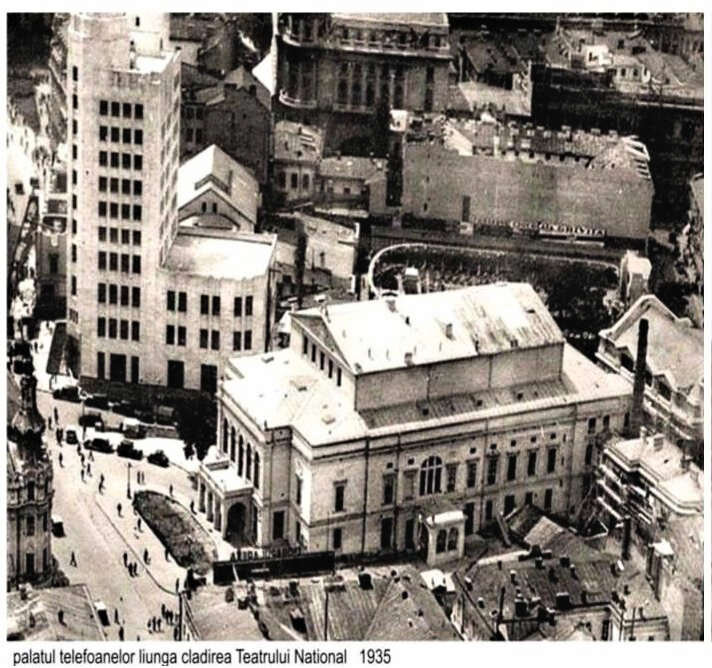

Planurile pentru reconstrucția nucleelor istorice ale orașelor trebuie să aibă la bază o evaluare istoric-evolutivă a orașului, axată pe identificarea proceselor ce au dus la formarea configurației urbane și a fondului construit și pe cunoașterea efectelor acestor procese asupra componentelor materiale ale elementelor construite pentru a preveni pagubele provocate de cutremure. Scopul constă în asigurarea că percepția istorică a mecanismelor de dezvoltare a orașului joacă un rol din ce în ce mai activ în acțiunile de conservare (fig. 4-5).

„Pe de altă parte, extinderea noțiunii de monument istoric la diferite situri și scări duce la apariția unor noi subiecte de critică și interpretări referitoare la «caracterul locului», ceea ce presupune utilizarea unor instrumente de intervenție adecvate din domeniul planificării urbane și al metodologiilor amenajării teritoriului în strânsă legătură cu instrumentele de restaurare” (D’Avino, 36).

Având în vedere tiparele caracteristice de construcție prezente în nucleele istorice ale orașelor afectate de seism, trebuie evitate abordările ce presupun demolarea completă și reconstrucția de la zero și riscurile asociate legate de pierderea permanentă a elementelor de identitate și memorie. Procesul de restaurare trebuie să se bazeze pe recuperarea și restaurarea elementelor care au supraviețuit cutremurului, chiar dacă este vorba doar despre configurația urbană (piațete, rețele stradale și de transport, planuri de locuințe etc.). În planul de reconstrucție al orașului Venzone se menționa că până și zidurile simple rămase în picioare ar trebui păstrate, pentru că „ofereau o coerență a locului, un reper material și moral pentru a o lua de la capăt, proba tangibilă a continuității locului în interiorul locului însuși (...); mai presus de toate, acestea reprezentau o graniță extrem de precisă” (Doglioni, 72).

În mod similar și în virtutea faptului că obiectivul principal este păstrarea semnificației unui loc dat, este de la sine înțeles că sunt interzise orice operațiuni care modifică rețeaua de drumuri sau parcelările, deoarece acestea reprezintă un document solid, recognoscibil și extrem de valoros ce oferă cele mai legitime dovezi ale structurii antropice inițiale a sitului. Relația dintre oraș și mediul înconjurător determină și modelează întreaga sa structură, de la rețeaua stradală și de transport la forma ansamblurilor de locuințe, a clădirilor și a spațiilor cu care interacționează.

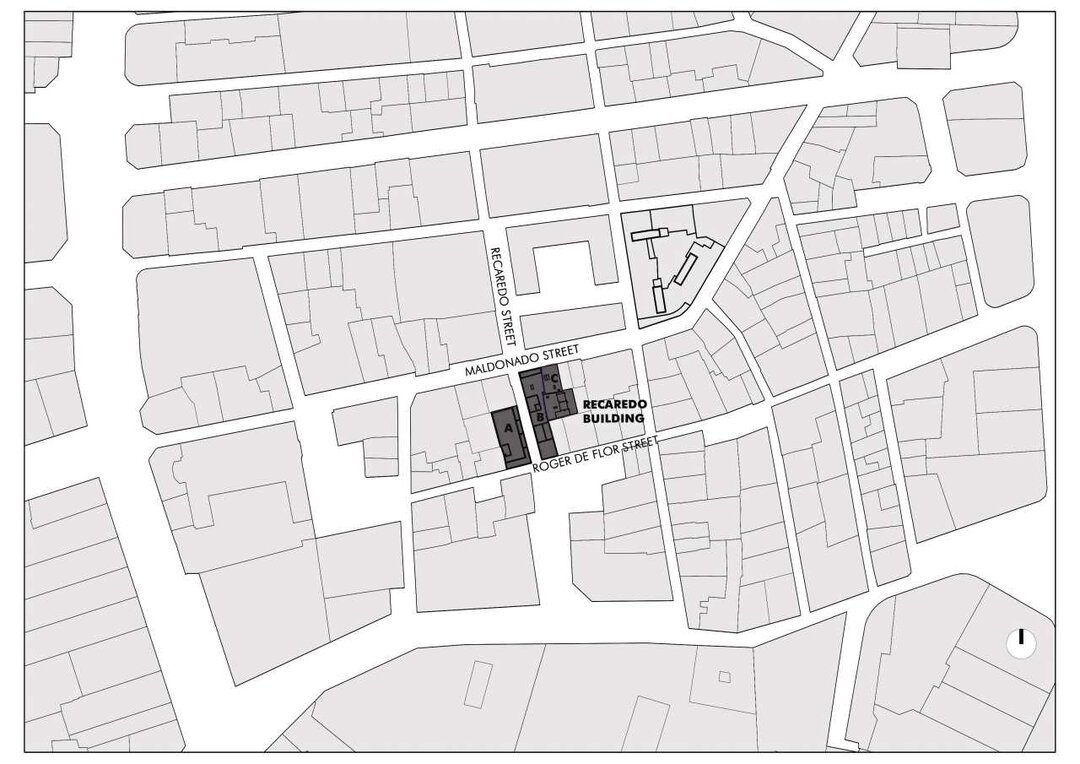

Niciun organism urban nu trebuie privit doar ca simpla sumă a părților sale, ci analizat în lumina relațiilor complexe dintre diferitele sale elemente constitutive, ceea ce înseamnă că orașele trebuie văzute ca fiind rezultatul unei serii de procese, al unui șir de modificări petrecute de-a lungul anilor, toate contribuind într-o manieră identică la autenticitatea orașului și la conturarea identității locului (fig. 6).

Înțelegerea critică trebuie să se extindă astfel încât să ia în considerație spiritul locului, încercând să determine vocația arhitecturală, legăturile cu contextul și relațiile spațiale cu mediul înconjurător, toate acestea, analizate separat de concepția geometrică, matematică sau rațională a spațiului, dovedindu-se mai incisive datorită intuiției și emoției.

Astfel, extinderea cadrului de analiză este un lucru bun, pentru că facilitează legăturile cu proiectarea urbană și planificarea spațială, dar având ca obiectiv principal asimilarea celor mai expresive caracteristici figurative și spațiale și, ca rezultat, un control formal mai exact al eforturilor depuse: practic, „o legătură între urbanism și arhitectură diferită de cea promovată de cultura oficială” (Portoghesi, 45), în cadrul căreia transformările nu sunt planificate la scara „perspectivelor aeriene”.

Într-un context atât de vast și fragil deopotrivă, nu poate exista nicio celulă urbană sau ansamblu de clădiri care să servească drept catalizator pentru realizarea unei reformulări; de fapt, astfel de entități trebuie privite ca parte a unui întreg, a unui context mai amplu, cu valoare care răzbate mai departe, ca „elemente ale unui limbaj, asemenea unui cuvânt plasat în cadrul unei locuțiuni prepoziționale: acesta servește la construirea sensului frazei fără a avea un sens în sine” (Cacciari, 11). Văzute ca elemente de limbaj, entitățile urbane trebuie să accepte schimbarea, transformarea, reutilizarea, adaptarea la condiții variabile sau sensibilitatea critic-perceptivă proprie vieții moderne.

Un alt subiect de reflecție este conservarea sitului, a sedimentării sale lente în cadrul mediului înconjurător, o ilustrare a ceea ce Lewis Mumford numea „sufletul orașului”, valabile în mod cert pentru centrele urbane de mici dimensiuni, cum ar fi Cerasola, Chiavano (fig. 7) sau Castel Santa Maria. În Umbria, unde nucleele așezărilor sunt caracterizate de o îndelungată istorie a contextului și o morfologie distinctă a rutelor și geometriilor, diversificate și stratificate de-a lungul secolelor, conservarea sitului original are o importanță capitală.

Reconstrucția-relocarea lor ca urmare a distrugerilor cauzate de cutremurul din 1979 au anulat definitiv orice urmă de memorie evolutivă, precum și o parte importantă din cultura tehnică a regiunii; pe de altă parte, nici conservarea bazată pe selecția istorică nu ar fi fost acceptabilă în acest caz, având în vedere că un nucleu urban este, prin însăși natura sa, un prezent istoric în continuă evoluție, care există în afara timpului, sau caracterizat de o viziune istorică tributară conceptului diacronic al schimbării evolutive. Aceasta este istoria contextuală redată de artefactele materiale încă organizate în concordanță cu sistemele morfologice și spațiale, constituind mărturiile care fac posibilă repovestirea trecutului.

De altfel, nici Cesare Brandi nu este de acord cu „dezasamblarea și reconstituirea unui monument în alt loc decât cel pe care a fost construit, considerând că o asemenea lipsă de legitimitate ar contribui mai mult la subminarea argumentelor estetice decât a aspectului istoric, că alterarea caracteristicilor spațiale ale unui monument îl va compromite ca operă de artă” (Brandi, 78).

Further perplexity arises with regard to the extent of the damage caused by the quake, the geological insecurity of the zones struck, the lack of security of the historic structures, in terms of both the urban layout and the individual constructions, as well as the depopulation of the mountain areas in question, something that has been occurring for a good many decades.

There can be no question that similar restoration projects must be approached at scales that can vary, ranging from individual buildings to an entire urban population centre to the landscape as well.

A plan for the reconstruction of the historic cores of towns should be inspired by an historical-evolutionary assessment of the city or town focussing on recognition of the processes that led to the formation of the urban layout and the constructions, as well as acquisition of knowledge of the effects of these processes on the material components of the constructed elements, so as to prevent damage triggered by earthquakes. The objective is to ensure that historical knowledge of the mechanisms through which the city or town developed play an increasingly active role in activities of preservation (fig. 4 - 5).

“Extension of the status of monument to different settings and dimensions, on the other hand, gives rise to new issues of criticismand interpretation regarding the ‘sense of place’ and requiring, as a result, the use of suitable tools of intervention tied to the discipline of urban planning and to the methodologies of territorial planning, to be used hand in hand with the instruments of restoration” (D’Avino, 36).

Precisely on account of the distinctive construction formats found in the historic cores of the towns struck by the earthquake, care should be taken to avoid approaches involving complete demolition and subsequent rebuilding from scratch, with the risk of a further and lasting loss of elements of identity and memory. The process of restoration must be based on the recovery and restoration of what has survived the earthquake, even when this means nothing more than the urban layout (piazzas, routes of streets and roads, formats of homes etc.). The plan for the reconstruction of Venzone specified that even simple walls were to be preserved, seeing that “they provided a consistency of place, a material and moral support from which to start anew, tangible proof of the continuity of the place within the place itself (…); above all else, they constituted an extremely precise boundary” (Doglioni, 72).

In the same way, and precisely because the chief objective is preserving the meaning of a given place, it goes without saying that operations which modify the existing layouts of roads or land divisions cannot be allowed, seeing that they still represent a permanent, recognisable and highly valuable document, providing the most authentic evidence possible of the initial manmade structuring of the site. For the relationship that the town or city established with its surrounding context effects and moulds its entire structure, from the layout of routes and ways to the form of blocks of buildings, even the forms of the buildings themselves and the spaces within which they interact.

No urban organism can be considered the mere sum of its parts,but must be seen in the fullness of the complex relations between its various constituent elements, meaning that towns and cities must be viewed as the outcome of a series of processes, of a sequence of modifications that occur over a lengthy span of time, with all of them contributing in indistinguishable fashion to the authenticity of the town or city, as well as to the formation of its identity of place (fig. 6).

Critical understanding must be extended to take into consideration the sense of place, attempting to determine the architectonic vocation, the connections with the surrounding context and the spatial relations with the environment, all of which, apart from any geometric, mathematical or otherwise rational conception of space, prove to be more incisive, by dint of both intuition and emotion.

And so an extension to broader settings is in order, links to urban design and planning, but with the primary focus on the assimilation of the more expressive figurative and spatial characteristics and, as a result, a more accurate formal control of the entire effort: almost “a different liaison of urban planning and architecture than that endorsed by official culture” (Portoghesi, 45), under which transformations are not planned on the scale of ‘aerial views’.

Within such a vast yet feeble context, there can be no single urban cell or block of buildings that serves as the catalyst for carrying out a reformulation, but rather such entities must be viewed as a part of a whole, an entire context, possessing a value that reaches even further, as “elements of a language, as a word placed within a prepositional phrase: serving to construct the meaning of the phrase, but without any meaning in and of itself” (Cacciari, 11). And as a language, it must accept change, transformation, reuse, adjustment to changed conditions, the different critical-perceptive sensibility inherent to modern life.

Another topic for reflection is the preservation of the site, of its slow sedimentation within the surrounding context: what Lewis Mumford referred to as “the soul of the town”. In particular, as is especially true for small-scale urban centres such as Cerasola, Chiavano (fig. 7) or Castel Santa Maria, in Umbria, whose core settlements are characterised by a lengthy history of context and distinctive morphology of routes and geometries that has been diversified and stratified in the course of centuries, preservation of the original site is of key importance.

Their reconstruction-relocation following the 1979 earthquake cancelled for all time any sign of evolutionary memory, together with significant portion of the region’s technical culture, nor would preservation grounded in historical selection be acceptable, seeing that an urban core is, by its very nature, a continually evolving historical present, existing outside of time, or rather characterised by an historical outlook tied to a diachronic concept of evolutionary change. This is the contextual history presented by the material artefacts still organised in accordance with authentic morphological and spatial systems, constituting evidence that can be used to recount the past.

For that matter, even Cesare Brandi is not in agreement with the “dismantlement and reconstruction of a monument on land other than where it was built, seeing that a similar lack of legitimacy would do more to undermine aesthetic considerations than the historical aspect, seeing that the alteration of the spatial features of a monument is bound to compromise it as a work of art” (Brandi, 78).

Referințe

BRANDI, Cesare, Teoria del restauro, Roma 1963 (2° ed. Roma 1972)

PORTOGHESI, Paolo, Le inibizioni dell’architettura moderna, Bari 1974

MALDONADO, Tomas, „Terremoto, quale ricostruzione”, Casabella, 470, June 1981, XLV, p. 7

SAMONÀ, Alberto, „Il terremoto della forma, in architettura e urbanistica”, Casabella, 470, June 1981, XLV, p. 10-15

CACCIARI Massimo, Relazione introduttiva, in G. Cristinelli, V. Foramitti, edited by, Il restauro fra identità e autenticità, proceedings of the roundtable, Venezia 31/1-1/2/1999, Venezia 2000, p. 11-16

DEZZI BARDESCHI, Marco, Lacuna, rovina, progetto, „’ANANKE”, n.s., giugno 2004, 42, p. 2-6

VARAGNOLI, Claudio, Tecniche costruttive tradizionali e terremoto, „Ricerche di storia dell’arte”, 99, 2009, p. 65-76

DOGLIONI, Francesco, Dopo quarant’anni di terremoti, „Ricerche di Storia dell’Arte”, 122, 2017, 67-77

D’AVINO, Stefano, After the Earthquake. The conservation before the conservation, proceedings of the International Conference „Protection of Historic Structures in Case of Emergency Situations”, Cluj-Napoca (România), 19-20 octombrie 2017, „Transsylvania Nostra”, 4-17, p. 34-40

References

BRANDI, Cesare, Teoria del restauro, Roma 1963 (2° ed. Roma 1972)

PORTOGHESI, Paolo, Le inibizioni dell’architettura moderna, Bari, 1974

MALDONADO, Tomas, ‘Terremoto, quale ricostruzione’, Casabella, 470, June 1981, XLV, p. 7

SAMONÀ, Alberto, ‘Il terremoto della forma, in architettura e urbanistica’, Casabella, 470, June 1981, XLV, pp. 10-15

CACCIARI Massimo, Relazione introduttiva, in G. Cristinelli, V. Foramitti, edited by, Il restauro fra identità e autenticità, proceedings of the roundtable, Venezia 31/1-1/2/1999, Venezia 2000, p. 11-16

DEZZI BARDESCHI, Marco, Lacuna, rovina, progetto, “’ANANKE”, n.s., giugno 2004, 42, p. 2-6

VARAGNOLI, Claudio, Tecniche costruttive tradizionali e terremoto, ‘Ricerche di storia dell’arte’, 99, 2009, p. 65-76

DOGLIONI, Francesco, Dopo quarant’anni di terremoti, ‘Ricerche di Storia dell’Arte’, 122, 2017, 67-77

D’AVINO, Stefano, After the Earthquake. The conservation before the conservation, proceedings of the International Conference “Protection of Historic Structures in Case of Emergency Situations”, Cluj-Napoca (Romania), 19-20 october 2017, ‘Transsylvania Nostra’, 4-17, p. 34-40

Fig 4-5: Centrul istoric al orașului Amatrice după cutremurul din 2016 / The historic center of Amatrice after the 2016 earthquake

Distrugerile produse de cutremur în Accumoli / Damages produced by the earthquake in Accumoli

Fig 1: Gibellina. Il Cretto (Alberto Burri, 1984-1989)

Gibellina. Il Cretto (Alberto Burri, 1984-1989)

Fig 2a: Centrul istoric al orașului Venzone după cutremurul din 1976 / The historic center of Venzone after the 1976 earthquake

Fig 3: Relația dintre fondul construit și context: Castelluccio (Norcia) / The relationship between built and context: Castelluccio (Norcia)

Fig 2b: Reconstrucția prin anastiloză a centrului istoric al orașului Venzone / Reconstruction by anastylosis of the historic core of the towns of Venzone

Fig 4-5: Centrul istoric al orașului Amatrice după cutremurul din 2016 / The historic center of Amatrice after the 2016 earthquake

Distrugerile produse de cutremur în Accumoli / Damages produced by the earthquake in Accumoli