Architectural regeneration is learned by doing

Architectural Regeneration:learning through practice

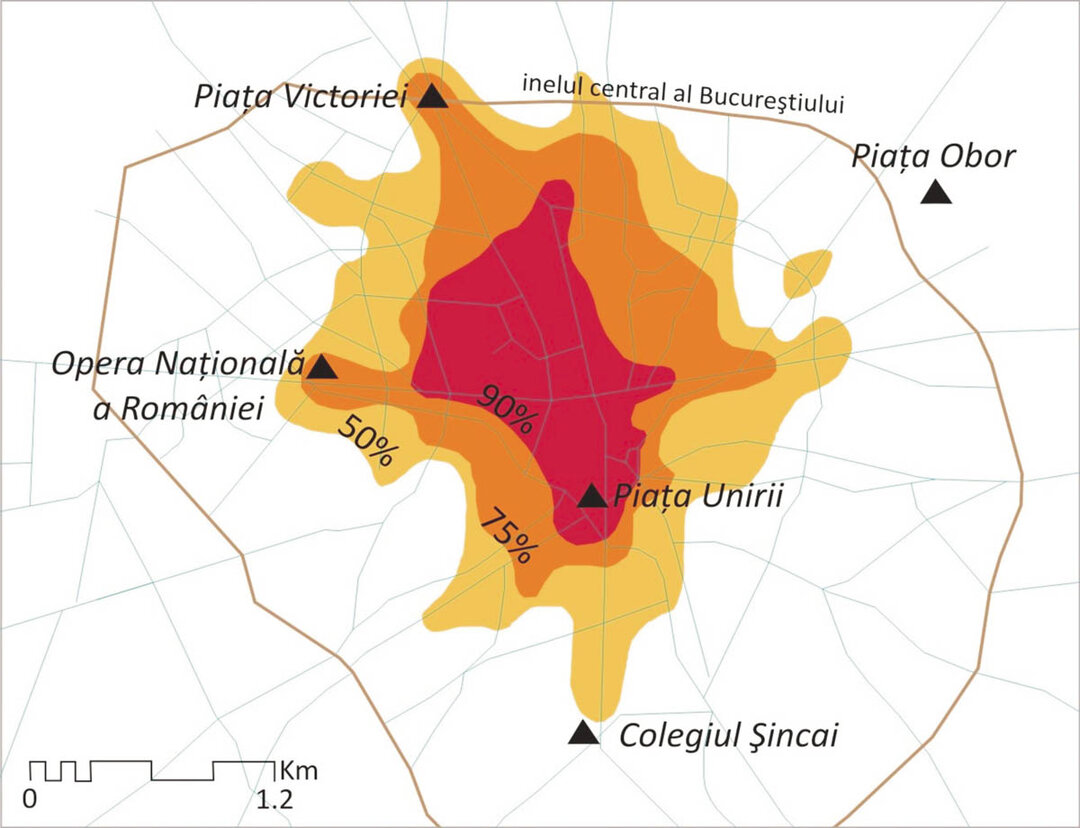

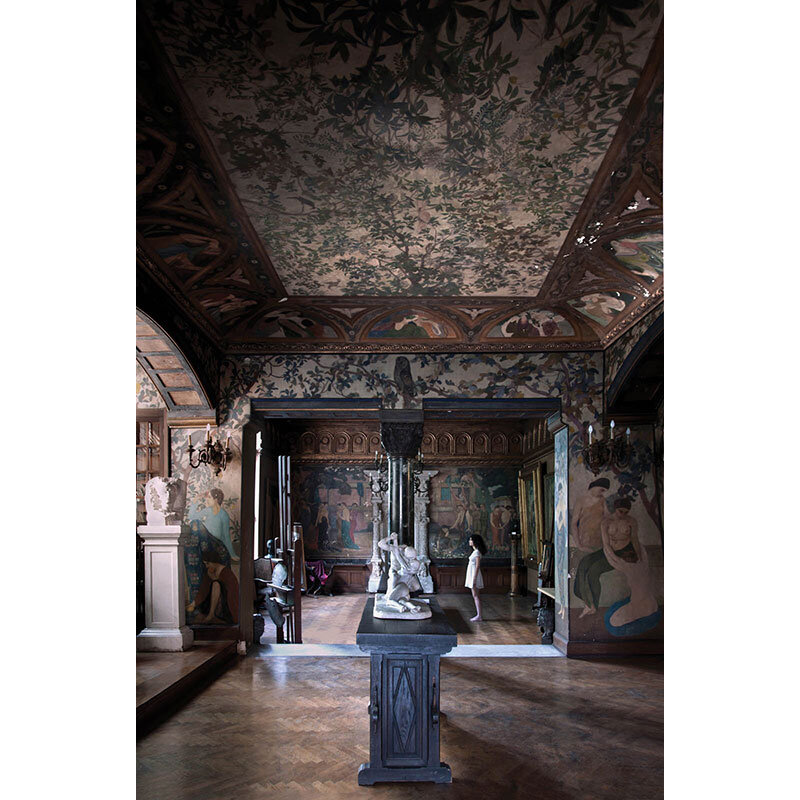

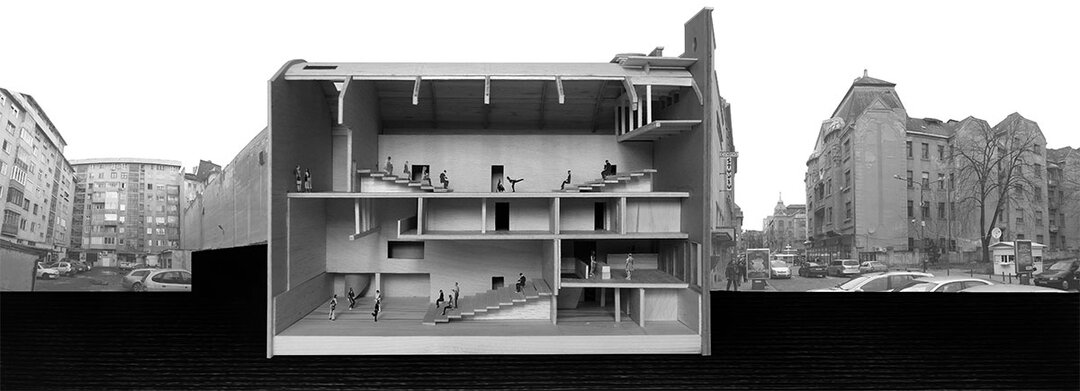

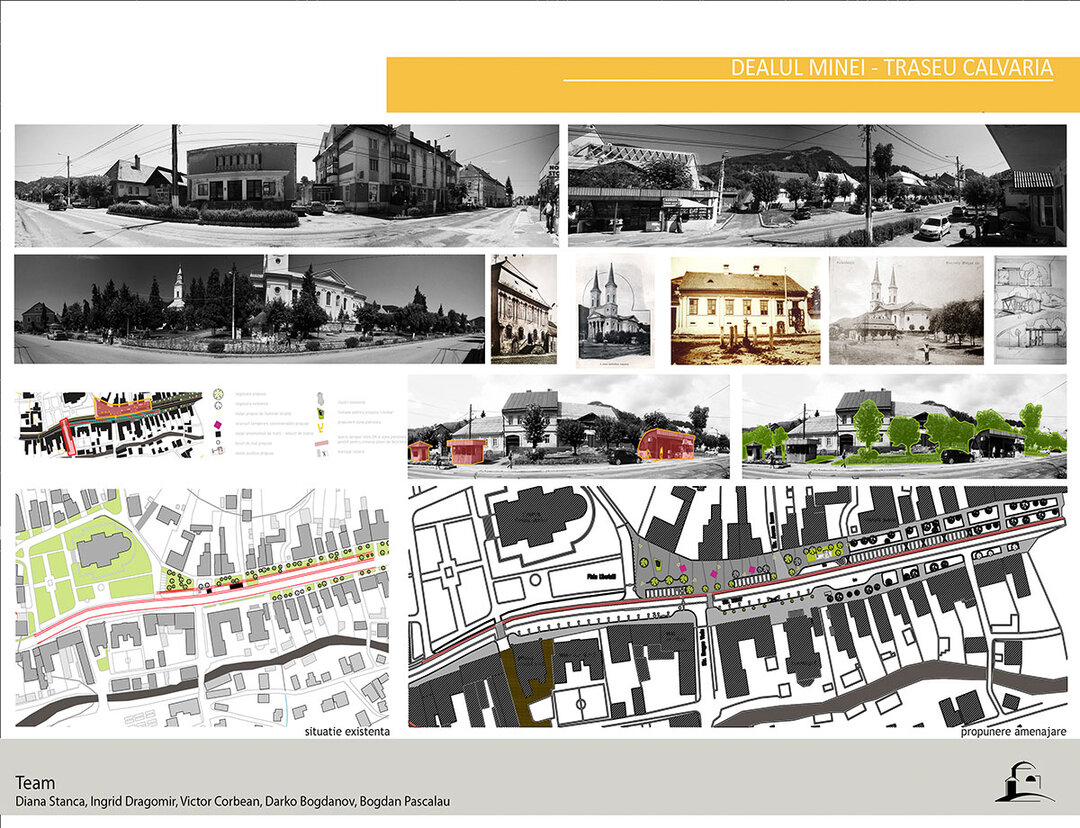

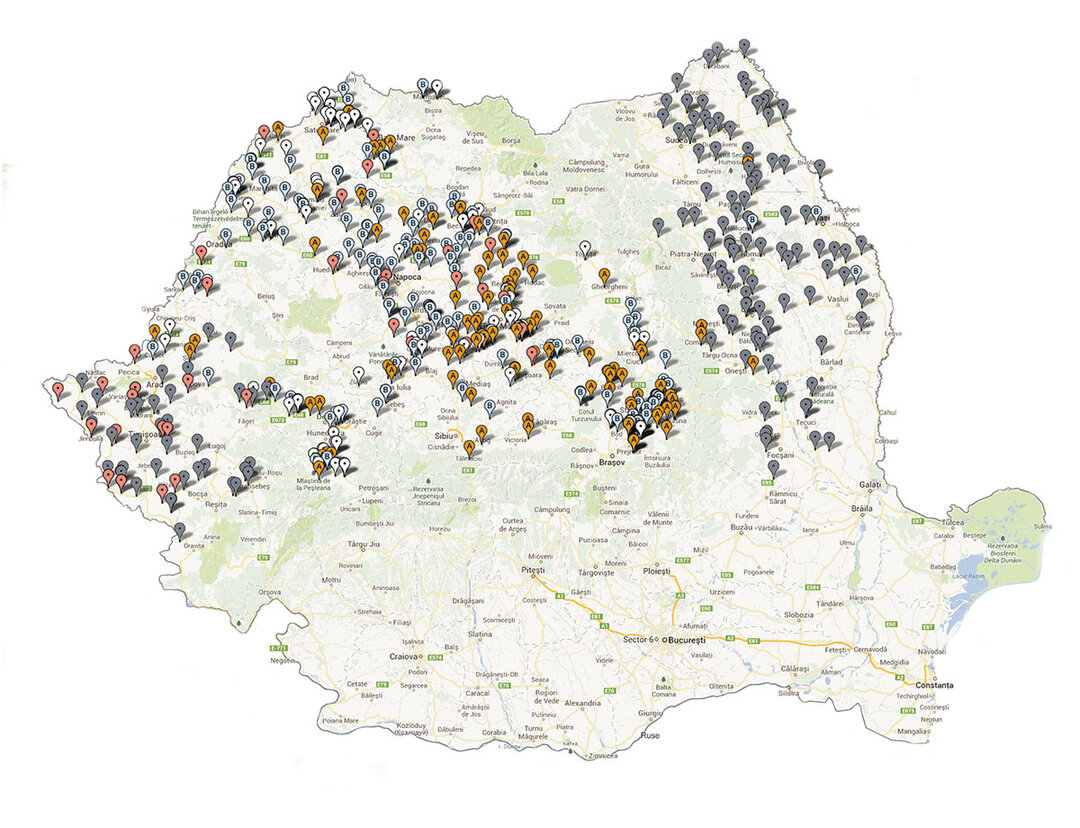

| In the UK there is strong evidence to show that a third of construction work is work on existing buildings - conservation, refurbishment, adaptive re-use and extension work, which make up a substantial part of the workload of many architectural practices. A similar trend can be observed in the rest of Europe, as urban density increases, brownfield sites are redeveloped and former industrial areas are incorporated into the fabric of the city. However, adaptive reuse is often seen as the poorer relative of 'design', particularly by architectural education and design offices. It is important to recognize that reuse and adaptation of the existing built environment often occurs in the wider context of urban or area regeneration, with associated social, economic and development concerns. Given the increasing emphasis on the sustainability of the built environment, there is a need to recognize the importance of creative and innovative approaches to the efficient re-use of the existing building stock and the endowing of dynamic and thriving urban areas with a sense of place. Now in its seventh year, Oxford Brookes University's International Architectural Regeneration and Development (IARD) Master's program at Oxford Brookes University builds on the common ground shared by fields as diverse as architectural anthropology, urban conservation, rural development and cultural sustainability, promoting an interdisciplinary approach that combines critical thinking and analysis with creative design. According to the definition, architectural regeneration consists of the collective activities of reusing, adapting and retrofitting existing buildings in urban or rural contexts in ways that recognize the impact these decisions and interventions have on the regeneration of a place, are underpinned by the principles of social, cultural and environmental sustainability. The Masters program emphasizes the regeneration of the historic environment in an international context using holistic approaches. Students come from all over the world and often have a wide variety of professional backgrounds. After graduating from the program they enter a broad international professional environment and often take active roles in the regeneration process. There is no 'one size fits all' in architectural regeneration; the programme aims to equip students with the knowledge and skills to deal with the many situations they will face in their future professional lives and to recognize the economic, social and environmental implications of their actions. A real project is therefore an important component of the one-year program, which aims to translate theory into practice and to involve students in a real and dynamic project situation. During fieldwork, students are expected to gather information through a variety of different methods and to assess a complex situation with a multitude of overt and hidden dimensions. Each year the field study and field project takes in different types of buildings in diverse rural and urban contexts. Projects to date have included proposals for the rural regeneration of two villages in the inland region of Valencia, Spain, faced with the loss of agricultural production and associated depopulation, urban regeneration interventions and the redevelopment of a school building in the center of Medina in Tunis, community-based approaches to regenerating degraded traditional buildings in Ras Al Khaimah, UAE, now inhabited by a large population of South Asian immigrants, which also took into account harsh climatic conditions and cultural conflicts, the re-use and regeneration of the Wolf factory site in Romania, in collaboration with colleagues from Ion Mincu University, and most recently, devising a way to revive the legendary 1950s Lijbaan shopping mall in Rotterdam, now a listed heritage site. These projects are just one illustration of the wide range of architectural regeneration projects that have ranged from small-scale vernacular buildings to 20th century modernist buildings. They play a particularly important role in contemporary cities and rural settlements, not only by enhancing the personality of a place or providing a connection with its identity, but also by providing economically and environmentally viable options for redevelopment and reuse. The activities carried out in Bucharest in 2012 highlighted the large number of existing buildings dating from the 9th and early 20th centuries with significant potential for reuse and creative intervention, in particular the large industrial building complexes that have come to occupy central and up-and-coming areas. Combining the economic and environmental benefits of reuse with creative solutions can generate unique urban destinations and can lead to the unification of a place's historic and contemporary identities. A one-day symposium held in May this year brought together several of our partners working in the field, eager to learn from the experience gained by architectural practices in architectural regeneration and to expand the theoretical framework of this burgeoning discipline. Presentations were given by Robin Nicholson - from Cullinan, Robert Adam - from ADAM Architecture, Geoff Rich - from Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, Niall Phillips - from Purcells, together with Trevor Osborne - from Trevor Osborne Property Group, and Tim Brennan - from the Regeneration Policy Service at English Heritage. The symposium highlighted not only the scale of architectural regeneration work currently being undertaken, but also its diversity. Ideally, in the process of regeneration and establishing new and viable ways of using existing buildings, architects should be involved from the outset of projects, as they often have a better glimpse of a building's potential and the creative ways in which it could be adapted. This kind of input is particularly valuable for owners, developers or other groups planning to invest in an existing building. On the other hand, it is equally important for architects to have a good understanding of the concept of feasibility in terms of project costs, cash flow management and the financial benefits generated through multiple revenue-raising options. The aforementioned feasibility presentations, which are also part of the project, came as a surprise to most students. However, several speakers at the symposium referred to the additional entrepreneurial role of the architect in providing creative project financing solutions. This was exemplified by Trevor Osborne, who is a developer and has assessed the potential of several existing historic buildings, including Oxford Castle. In the UK, the English Heritage organization strongly supports architectural regeneration and reuse of existing buildings. Its annual reports, Heritage Matters , highlight the economic viability of reuse and the social, community and cultural benefits that are often overlooked, while a number of case studies are reviewed in the latest issue of Heritage Works. And yet the long-term benefits of investing in the built environment of historic significance are unlikely to be of great interest to government agencies and politicians looking for investments that generate the quickest possible returns. This is also why it is crucial that architects have the necessary knowledge to understand and address the social, economic and environmental issues involved in regeneration and reuse. |

| For more details on the Master's programs in Regeneration and International Architectural Development visit: http://www.brookes.ac.uk/studying-at-brookes/courses/postgraduate/2013/international-architectural-regeneration-and-development/ The 2013 edition of Heritage Works can be downloaded at: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/heritage-works/ Follow the program on twitter: |

| Aylin Orbasli PhD in Architecture, Senior Lecturer in Architectural Regeneration at Oxford Brookes University and Theme Coordinator for the MSc program in International Architectural Regeneration and Development |

| In the UK it is well documented that an up to a third of the value of construction work concerns work to existing buildings: conservation, refurbishment, adaptive reuse and extensions, and thus makes up a substantial work load for many architects' practices. A similar pattern is observed across Europe, as urban densities are increased, brownfield sites redeveloped and former industrial areas incorporated into the city fabric. Nonetheless, adaptive re-use is often seen as the poor cousin to 'design', especially in the teaching of architecture and in the design studio. At the same time it is important to recognise that the re-use and adaptation of the existing building environment often takes place in the broader context of urban or area based regeneration, with associated social, economic and development concerns. With a growing emphasis on sustainability of the built environment the importance of creative and innovative approaches to effectively reusing the existing building stock and engendering thriving and dynamic urban areas with a sense of place has to recognised. Now in its seventh year the masters program International Architectural Regeneration and Development (IARD) at Oxford Brookes University builds on an understanding in the fields of anthropology of architecture, urban conservation, rural development and cultural sustainability, promoting an interdisciplinary approach that combines critical thinking and analysis with creative design. Architectural regeneration is defined as the collective activities of reusing, adapting and evolving existing buildings within an urban or rural context in ways that recognize the impacts these decisions and interventions have on the regeneration of a place, and are underpinned by the principles of environmental, social and cultural sustainability. The focus of the masters program is the regeneration of the historic environment in an international context employing holistic approaches. Students on the program arrive from all over the world and often have different professional backgrounds. On completing the program they enter a broad international professional field, often taking on active roles in the regeneration process. In architectural regeneration there is no "one size fits all" and the program sets out to equip the students with the necessary understanding and skills to cope with the many different situations that they will encounter in their future professional lives and to recognize the environmental, economic and social implications of their actions. A real life project is therefore an important component of the year long program putting theory into practice and enabling students to engage in a real and dynamic project situation. During the field work students are expected to gather information using various methods and appraise a situation of complexity and with a multitude of obvious and hidden dimensions. Each year the field study and project takes on different building types in varying rural and urban contexts. Projects to date have ranged from rural regeneration proposals for two villages in the inland region of Valencia in Spain, facing loss of agricultural production and associated depopulation; urban regeneration interventions and redevelopment of a redundant school building in the heart of the Medina of Tunis; community led regeneration approaches in the run down traditional houses of Ras Al Khaimah, UAE now inhabited by a largely South Asian immigrant population, also considering harsh climatic conditions and cultural conflicts; the re-use and regeneration of the Wolf factory site in Romania working with colleagues at Ion Mincu University; and most recently figuring out how to rejuvenate the iconic 1950s and now listed Lijbaan shopping precinct in Rotterdam. These projects are just an illustration of the wide remit of architectural regeneration ranging from small vernacular buildings to twentieth century modernist modernist icons. Notably, they all have a role to play in contemporary cities and rural settlements not only by enhancing character or connecting to place identity, but also as economically and environmentally viable options for redevelopment and re-use. Working in Bucharest in 2012 highlighted the rich array of existing buildings from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with exciting potentials for reuse and creative intervention, most notably large clusters of industrial buildings that have now come to occupy central and up and coming areas. Combining the environmental and economic benefits of reuse with creative solutions can make for unique urban destinations and a merging of historic and contemporary identities for a place. A one day symposium in May 2013 brought together some of our practice partners with the aim of learning from practices' approaches to architectural regeneration and to expand on a theoretical framework for this burgeoning discipline. Presentations were made by Robin Nicholson from Cullinan Studio, Robert Adam from ADAM Architecture, Geoff Rich from Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios, Niall Phillips from Purcells alongside Trevor Osborne from the Trevor Osborne Property Group and Tim Brennan from English Heritage's Regeneration Policy Unit. Not only did the day revealed the breadth of architectural regeneration work being undertaken in practice but also the diversity of this work. In the regeneration process and in determining viable new uses for redundant buildings, architects are best involved from the very start of a project, as they are often able to see the potential of a building and creative ways in which it can be adapted. This type of input is invaluable to owners, developers or other groups planning to invest in an existing building. On the other hand, it is also important for architects to have a good grasp of feasibility in terms of project cost, cash flow management and payback through various options of income streams. The feasibility lectures that are also linked to the project come as a surprise to most students. Yet, a number of the symposium speakers referred to the role of the architect also as an entrepreneur offering creative solutions to how projects are financed. This point was also exemplified by Trevor Osborne who is a developer who has been realizing the potential of redundant historic buildings including Oxford Castle. In the UK, English Heritage strongly supports architectural regeneration and the reuse of redundant buildings. Annual reports by English Heritage entitled Heritage Counts make a case for the economic viability of reuse, to orgetting the social, community and cultural benefits, while a series of case studies are examined in the recent Heritage Works publication. The long term benefits of investing in the historic environment, however, are often less likely to appeal to Government agencies and politicians seeking short term returns on investment. This is precisely why it is fundamental that architects are equipped to understand and deal with the social, economic and environmental concerns of regeneration and reuse. |

| To find out more about the masters in International Architectural Regeneration and Development:

The 2013 edition of Heritage Works can be downloaded from: http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/publications/heritage-works/ Follow the program on twitter: @archregen |

| Aylin Orbasli Doctor in Achitecture and Reader in Architectural Regeneration at Oxford Brookes University and subject coordinator for the MA in International Architectural Regeneration and Development. |