On the Heritage of Roșia Montană, with Hope

text: Claudia APOSTOL

If we look at our recent history, i.e. post-December 1989, we bitterly note that we can count on the fingers of one hand the moments when our society stood up to defend its cultural heritage. This fact can be explained, on the one hand, by our living in an Eastern European country, where the destruction of the heritage, of centuries-old houses and churches has become daily routine. Many of us have spent our childhoods in neighbourhoods which no longer exist nowadays, as they have been wiped out by bulldozers to make room for “progress”. Our society survived the trauma, but took an expectedly long time to make the transition from a mindset focused on the banality of evil and destruction to one focused on protecting and harnessing the cultural heritage. Furthermore, after the 1989 Revolution we were caught somehow off guard, with our senses and priorities numbed by the 50 years of communism, so we failed to stand up in due time to defend a number of valuable buildings or sites, lost in the name of the same alleged progress and well-being.

Three decades afterwards, although reality appears to be grim most of the time and daily examples come to reinforce such a perception, it is necessary to take a step back and look at the Romanian civil society from the outside, from beyond the frontiers of our all-pervading sorrow. It is not very easy to do so, especially for those involved day after day in a race against the clock for the safeguard of some heritage item, but it is necessary. Here is what the representative of the largest pan-European heritage protection association had to say: “I wish to congratulate Romanian civil society because, in my opinion, you are the Eastern European country most acutely aware of the important role played by cultural heritage in transforming your country” (Sneška Quaedvlieg-Mihailović, secretary of Europa Nostra), in the context of the conference entitled “The Future is Heritage”, held in Berlin. These statements do not spring from misinformation, but from the perspective of a federation of professional organisations involved in and connected to Romanian reality.

If we attempt the same exercise with Roșia Montana and make an effort to recall the general perception about the fate of the valuable heritage there, we shall recognise the same model: heritage a step away from imminent destruction in the years of communism (when the open-cast mining was started and an important part of the Cetate mountain was destroyed, along with a significant part of the Roman mines located therein), then abandoned to an investment that was disproportionate to the community, location and heritage, total lack of interest on behalf of the state authorities with respect to the heritage, even denial of its value and justification of destruction by all sorts of arguments never related to conservation or presentation, or to the care for the local community, culminating, in the last 5 years, in an unprecedented awakening of civil society in this respect.

Roșia Montană is not the first example of a protest (no matter how we understand protest, in any of its forms) in defence of monuments or heritage values, but was certainly the most relevant, vibrant and enduring action for retrieving what seemed already mostly lost, to those who joined the protests.

The enthusiastic movement of defence which mobilised organisations and citizens in 2013 may also be explained, at some point, by the people’s referring to what had already been lost. It was too much, unbearable, even. Enough is enough, like the Englishman says, and this was the case not only with respect to the heritage, but also with respect to the social and economic reality and to the impact produced on the environment by the massive mining project undertaken at Roșia Montană.

What is the Roșia Montană heritage discussed herein?

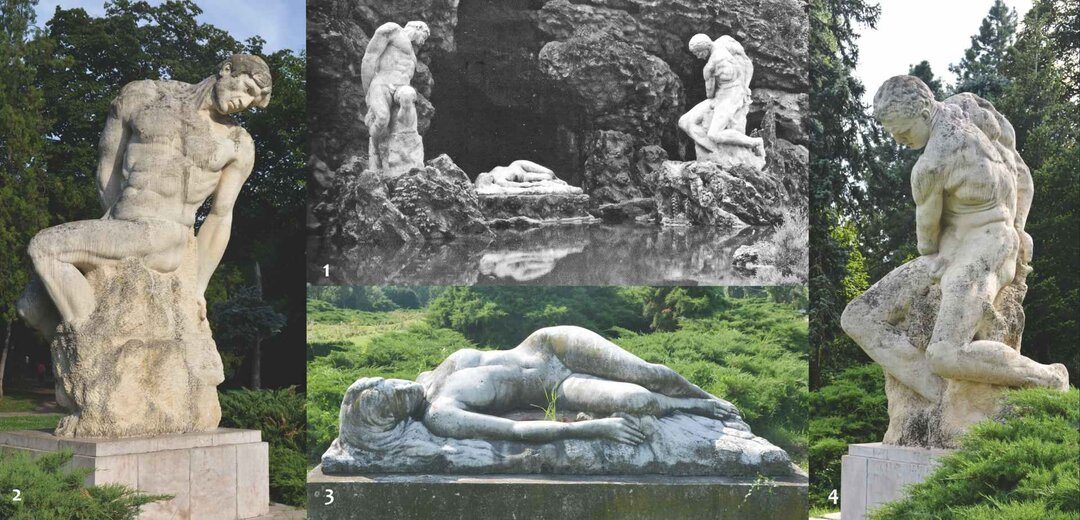

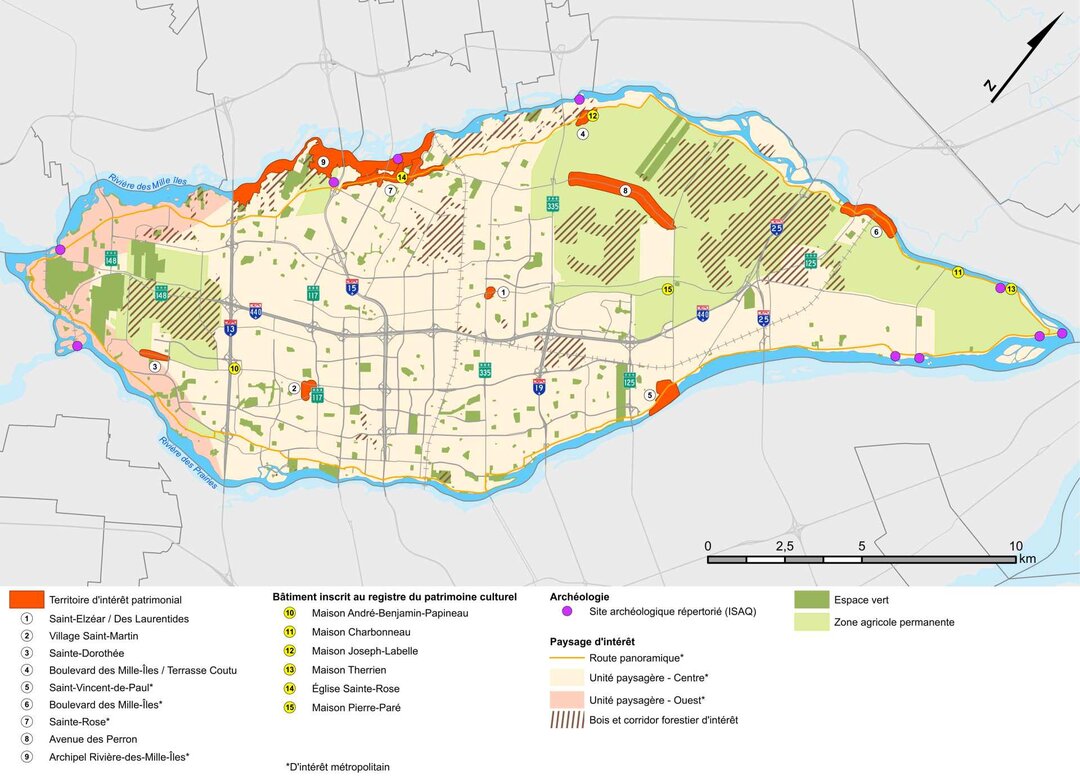

Roșia Montană boasts a wealth of valuable items coming together to form an outstanding site, a fabulous cultural landscape. The Apuseni Mountains area also boasts a number of other historical mining sites, none of which has preserved, however, such a rich collection of important vestiges, dating as far back as the prehistoric times, and going all the way to the modern and contemporary era and uniquely illustrating the evolution of mining.

If we were to refer to underground architecture, the best (and most competent) description would be that provided by ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites), UNESCO’s expert body competent in assessing Roșia Montana’s candidature for inclusion in the World Heritage List:

“The Roșia Montană cultural mining landscape contains the most representative example of Roman underground gold mining in the world and illustrates the exchange of values, through innovative techniques developed by the skilful Illyrian-Dalmatian immigrant miners for mining the gold through methods adequate to the technical features of the deposits. The multiple rooms which housed wooden drainage systems with discharge wheels actuated by human movement are a technique presumably brought from Hispania to the Balkans, while the galleries dug in perfect trapezoidal cross-section, the helical pits, the sloping communication galleries with stairs hewn in the mountain rock and the overlapping vertical extraction areas, with ceilings carved into steps, stand as an ensemble that is so specific to Roșia Montană as to suggest it belongs to a pioneering era in the technical mining history.

The Roșia Montană cultural mining landscape illustrates the Roman Empire’s strategic control over and intense development of mining in precious metals, an essential undertaking to its longevity and military strength. After the decline of mining in Hispania, Roșia Montană, located in Aurariae Dacicae (Roman Dacia, 106-272 AD) was the only new significant source of gold and silver of the Roman Empire and, most likely, one of the key reasons why Traian conquered it”1.

Regarding the built and industrial heritage preserved at Roșia Montană, the descriptions which accompanied the UNESCO candidature file, prepared by the specialists within the National Heritage Institute are, perhaps, the most eloquent:

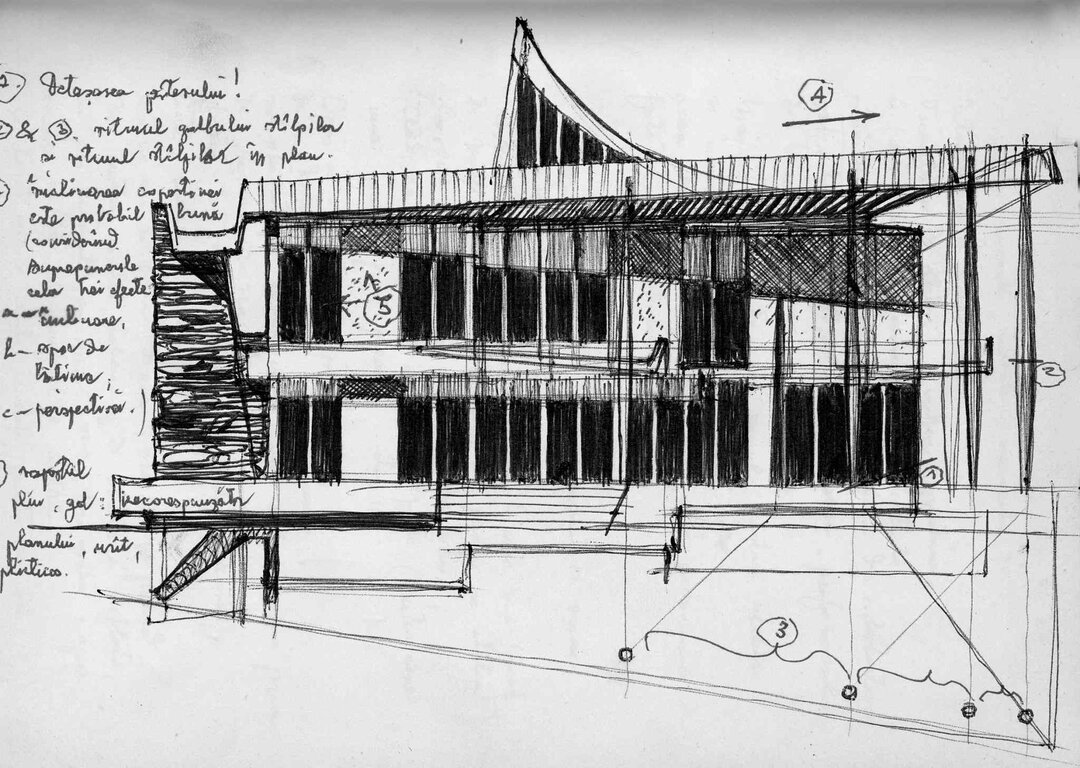

“The Roșia Montană village prides itself on an impressive inventory illustrating the various architectural styles–eclectic influences mixed with the local tradition–a cosmopolitan settlement the roots and setting of which have sprung from the unfettered mining of gold. The characteristic buildings with târnaț [a local porch] form the background typology for a series of other distinctive, mainly decorative, features, which have been borrowed from the repertory of baroque and classical architecture. This structure, which also stands out through its massive walls and monumental gates lining the winding roads, progressively makes way for the industrial suburbia housing the miners’ dwellings, buildings with a wooden ground floor and stony basement, many of them incorporating workshops for the processing of minerals with water basins supplied by springs, which could be used even in the coldest of winters.

Archaeological testimonies survive next to the legacy of the modern underground mining operations, while the landscape furnishes the evidence of how it was gradually and increasingly altered to suit the mining activity, the lifestyle of its communities, under the successive control of empires and of the state”2.

What stance has the Romanian state taken with respect to the Roșia Montană issue over time?

Roșia Montană is not just a place promoted by the civil society as worthy of being conserved because it is valuable. Far from that, actually. Ever since 1992, Roșia Montană has been included on the first List of Historical Monuments drawn up after the fall of communism. In fact, the Roșia Montană heritage currently protected by law was also protected in 1906, as it was on the List of historical monuments of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. If we were to take 1992 as a strict point of reference, we would be dealing already with decades of inaction on the part of the state, and, once the intentions to restart the large-scale mining operations became clear, we would also be dealing with complicity, bad faith and law infringement. Never once, over the 20 years of debates on a potential gigantic mining project taking place here, has the fate of the heritage been a priority for the authorities. There were only a couple of notable exceptions, such as including the site on the UNESCO indicative list3 and submitting the related file to UNESCO, actions achieved during the mandates of Mr. Vlad Alexandrescu and Ms Corina Șuteu, which were subsequently refuted anyway by other measures of the same ministry. Apart from that, in contradiction with the law and their duties, the reactions of the Ministry of Culture have varied, over the years, from a shameful but healthy shunning of any responsibility, practiced by Kelemen Hunor or Puiu Hașotti, to the unlimited support granted to the mining project by Răzvan Theodorescu or Daniel Barbu. In terms of declarations, something always seemed to be happening; when it came, however, to the protection or safeguarding actions directed at this exceptional site, the situation was much simpler: the Romanian state has done nothing for the Roșia Montană heritage. In fact, the only notable heritage protection action taken by such ministry and worthy of being mentioned was the UNESCO effort, i.e. submitting Romania’s candidature before the World Heritage Committee meeting in Bahrain this summer. Unfortunately, this instance of mobilization failed once more to focus on safeguarding the site, concentrating instead on sabotaging its prospects for development and the recognition of its value.

For those who are less familiar with the UNESCO procedures, including specialists in heritage protection, what happened in Bahrain left a lot of questions behind. Romania submitted for assessment an exceptional file, and the Committee experts issued the recommendation of inclusion for Romania. And what did the Romanian state do? Well, it requested the return of the file.

The positions taken by the ministry and the minister of culture, attempting to justify the governmental decision, did not help one bit in clarifying the situation, on the contrary, they added fuel to the fire and incited to manipulation. A lot of technical terms were employed, as well as references to procedures that were not particularly well-mastered or, which is more serious, were knowingly used erroneously to distort the real meaning of what had happened during the Committee’s debates. The entire episode was given a triumphant populist twist in the media by the authorities, when, in fact, any other European country signatory of the World Heritage Convention would have deemed this a very sad and highly embarrassing situation. Several terms such as “postponement” were used, although the Romanian state had not requested a postponement. References were made to precedents (Canada and France-Belgium), but these precedents do not bear any comparison with Romania’s case. Moreover, a summary of such cases suffices to show us that Romania had been incapable of keeping up with the heritage approaches and discussions carried on at such level. Two years before, Canada had requested a “referral” (return of the file to the state) for a file for which it had received a recommendation of inclusion. But the comparison ends here. The reason of that request had been the state’s wish that the management strategy assumed for the immense site with which they applied be also assumed individually, by each of the parties concerned and involved, down to the smallest detail. The situation was unpredictable and had been caused by the death of one of the leaders of the coalitions of native populations which had requested the inclusion. The Canadians wished that the person taking his place in the leadership of the coalition also take an active part and assume the strategy and the responsibilities. For us, Romanians, who are rather used to running away from responsibilities, such an approach is hard to understand and relies on a type of institutional and individual commitment with no match in our recent history concerning the heritage.

The other example used as a so-called “precedent”, the France-Belgium file, was in fact a request for “postponement” (the only one ever submitted in the history of the Committee), and had been filed by the assessing body, ICOMOS, and not by the state member of the Convention. Moreover, Romania did not apply for postponement, but referral in order to effect changes. There end the similarities between the exceptional situation generated by Romania and the other examples mentioned by minister Ivașcu.

In fact, Romania requested the return of the file through an amendment submitted by Azerbaijan, invoking arguments lacking any connection whatsoever to the protection of the heritage and its fate – the Committee’s sole topic of debate. Once submitted, this amendment was taken up for debate by the Committee, whose members could not vote for inclusion against the will of the state. They nevertheless deemed it appropriate to include in the decision a number of recommendations for the Romanian state. All these are never referred to in the positions of the Ministry of Culture or of minister George Ivașcu, although they form the roadmap that Romania must observe in the future: management plan, protection measures, collaboration with the assessing body etc. The press release of the Ministry of Culture makes no reference to the reactions of the Committee member states, which expressed their amazement with respect to the state’s request and declared they had been willing to vote for inclusion (in the UNESCO List, as well as in the List of Endangered Heritage). Likewise, the authorities made no reference to how the recommendations included in the Committee’s decision would be implemented.

To conclude, this very sad event, which could have resulted in the inclusion of Roșia Montană in the World Heritage, is the starting point for what the Romanian state, the specialists, the persons interested in the fate of the heritage, or the mere citizens need to do. It is a door that we momentarily slammed in our own face, but also a fundamental step taken towards the recognition of the universal value of this place, which is now on the radar of the most competent international institutions. It is also, hopefully, a door slammed in the face of those who until recently have minimized any efforts made to protect and highlight Roșia Montană’s heritage. And this list is a long one: from former ministers of culture to specialists contractually hired to defame the value of Roșia Montană’s heritage to worthless prime ministers who, in utterly debasing and embarassing statements recommended that we completely disregard this heritage.

The current state of affairs and what may come next

In an address given at the Film and Historical Accounts Festival in Râșnov, Romania’s ambassador to UNESCO, Mr Adrian Cioroianu, stated: “I do not think any mining will ever be possible again in the Roman mines area. The recommendations given and the assessment made by ICOMOS are so clear, that anyone attempting to mine there would take on some very serious risks. The assessment states very clearly: this area is unique in the world!”. His Excellency’s statement is highly optimistic considering the recent history of the Roșia Montană area, as well as the political context in Romania, a permanent risk factor forbidding us from engaging in any debates, evaluations, short or long-term strategies concerning the heritage. However, if we manage to overlook the recent fierce attack on the regulations concerning building permits and cultural and natural heritage protection, our ambassador’s assertions might evoke a state of affairs which might define normality. But these things are not sufficient!

It is not sufficient “not to touch” this site; on the contrary, Roșia Montană needs rapid and consistent intervention. If the commitments assumed by Romania, through its representative, before the World Heritage Committee, are real, then before long we should witness a fantastic mobilization on the part of the state in order to save this heritage de facto: direct measures, adequately financed, to restore the most important cultural and historical landmarks in the area, concrete measures to unblock the local urban planning regulations (the general urban plan has ceased to exist for years, it was annulled in court, and the development of a new plan, mandatory by law, is consistently blocked by Roșia Montană Town Hall) and the inclusion of clear provisions on heritage, actual encouragement measures targeting the owners of historical monuments, immediate measures dedicated to the network of historical galleries – and the list might go on. These measures are provided in the very decision of the UNESCO Committee, before whom the Romanian state has undertaken to do its utmost to protect its cultural heritage.

It is evident and also sad that this will not be the Romanian state’s last disregarded commitment in relation to the heritage under its care. However, unlike other times, these commitments were undertaken before the most important institution dedicated to heritage protection, to which Romania has responsibilities and to which it also pays an annual fee. We should point this out whenever we get the chance: we hope that the time when State representatives could afford to ignore and despise Roșia Montană’s heritage has passed, as it is now legally classified and protected under the international conventions.

One thing is certain: apart from monitoring the above-mentioned actions, it will be incumbent on the same civil society I was referring to above to play a more active role in encouraging heritage protection and in proposing development solutions based on the heritage as resource.

Whether we are talking about concrete measures aimed at involving the active citizens, refurbishing the valuable houses (as has been the case since 2012 under the “Adopt a House” programme”) or encouraging cultural tourism in the area (by organising a number of events, supporting the more active inhabitants etc.), it is important that Roșia Montană enjoy ongoing support from the civil society in the years to come. It is a drop in an ocean, desperate measures compared to the needs and the value of the site, but they still are the seed for something consistent and sustained that we together as citizens, specialists, organizations, political actors etc. need to define and in which we need to get involved constantly. Unfortunately, when it comes to heritage, it is not sufficient to protest in the street, to monitor and to react publicly, although one must admit that without the large-scale protests mounted in 2013 or the consistent reactions on the part of the civil society, including in court, we would not have been able to talk about Roșia Montană these days, let alone about its inclusion in the World Heritage List. At least in this case, the safeguarding of a heritage site has proven to be, for the most part, a long-lasting and exhausting battle, consuming a lot of time and energy. But we need to remind the more sceptical ones that these measures do pay off. They tend to multiply and nowadays we are able to witness similar gestures and alliances investing a formidable amount of energy to defend other sites or monuments, as well.

And this alone may be a clue that the Romanian civil society has grown extremely aware of the important role played by cultural heritage in transforming the country and is utterly capable of restoring and making best use of such heritage.

Notes

1. https://rosiamontana.world/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/whc18-42com-8B-en_RO.pdf

2. rosiamontana.world

3. https://patrimoniu.ro/monumente-istorice/lista-indicativa-unesco și

http://whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6082/