Binaries and Trinaries. A Summary of the Heritage Values

Essay

Binarii and trinarii.A recapitulation of patrimonial values

text: Anca Sandu TOMASZEWSKI

Innocence or too much brains

In 1945, Le Corbusier proposed a functional and radical reconstruction project for Saint Dié, with zoning, boulevards and eight Unités d'Habitation, which, of course, he presented simultaneously to the whole world. But just when it was attracting the admiration of architects and politicians, the local community, the unsuspecting provincials of the Vosges mountains, socialists and non-socialists, people from all walks of life, fought back. They rejected the project in corpore and the mayor obeyed. No one wanted to live in towers and lose their inherited living environment. Le Corbusier was consoled by a young industrialist who hired him to build a factory for women's bonnets on the side.

And the good Palladio longed to erect a beautiful, rhetorical edifice in a large square created for him in the historic city of Venice. As retrograde as the Vosges, the Venetians, accustomed to the medieval scale and their eclectic taste for merchants and sailors, steadfastly avoided it. They didn't want, it seems, a tear in the urban fabric, with its attendant losses, in exchange for a palazzo with a unity of style, isometrized in space like a church. They finally admitted him, in his old age, but still outside the city, in the skyline, to San Giorgio Maggiore and the Giudecca.

Since the Renaissance, then, there have also been happy events in which the common sense of the innocent has defeated the onslaught of the star architects who blindly over-authorized their own architectural ideologies. As in the old children's game "Twenty stout-hearted dwarves fighting two hedgehogs", sometimes the dwarves won. But when policy-makers have fallen under the spell of renowned architects with hegemonic tendencies, the hedgehogs have won. Barcelona, to boast of a Richard Meyer product, planted it in the Bario Gotico in the middle of a large Baroque-like square, according to them, a space worthy of the new "monument" but not of the medieval fabric - according to me. It was their way of understanding the old-new dialog in the historic urban space and a reverence to Richard Meyer and his love of modernism.

Let us not be mistaken, however, about popular discernment either. It has also produced catastrophic destructions such as the disappearance of civilizations, and losses such as the most recent ones in the Middle East, but also simply unfortunate solutions. Transylvanian communities, who 25 years ago threatened to burn down the wooden church if they were not allowed to clad it with a shiny new one, are still winning the game. They, the old churches, have escaped demolition, but not the humiliation of the big, lofty, new, walled edifices that still strut strut their stubborn faces in front of them on the national highway.

In the last case, however, it's not the dwarves who are evil. It is not the ignorance of the masses about the aesthetic theory of authenticity, nor their lack of affinity with their own memories of place that are the real culprits, any more than their shaky education is the fault of the masses. The culprits are the archists, who impose outdated utilitarian traditions in mummified form without alternative, so that the poor people perceive them as obstacles to their emancipation. Instead of ethno-religious and nationalist-patriotic demagoguery, they needed to be delivered convenient solutions for both local and general interest. Through intellectual flexibility and administrative skill they were found. Thus, like the Corbusian dogma of functionality, even the magnanimous intention of safeguarding the heritage could not be imposed on the people against the circumstances.

In fact, the enlightened minds were tacitly convinced from time immemorial that the issue of respect for the significant witnesses of the past could not be left to popular common sense, and they personally took it up. They have also personally fallen into the error of promoting their theories, because where there is a great deal of brains, there is... a loophole. Herodotus was still emphasizing the value of the vestiges of the past, fearing that they would perish like Atlantis somehow1. Many were his critics. Not all medieval Christians approved of the vandalization of pagan monuments. The learned clerics deplored it. They emphasized the historical value of the vestiges, and even extra-cultural values, such as the investment of human and material capital, but they were too little receptive to aesthetic value. Then the passions sharpened. The Italian Renaissance devoted itself with all its heart and mind to the protection of historical monuments, but only of Greco-Roman Antiquity, which interested it keenly. They persecuted "Gothic" because it was barbarous and distasteful.

England, on the other hand, never thought of abandoning its traditions, neither the generic Gothic nor the vernacular. They admitted a Christopher Wren up to a point, but Pugin jumped like a burnt pig when they began to flood their living environment with classicism, and not only that composed by the hand of a Wren, but also by the second and third hands, bordering on... all in bad taste2. So it's good to learn from the English. However, carried away by the tide of pleading, they also had their little slip-ups. Even William Morris, the founder of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, who has done admirable work in the field and has written theses that are still valid today, was prepared to demolish whole areas of Georgian urban fabric, which he saw no merit in. He has excuses. He even said it in utopian fiction3. He also hoped that one day "we will have an architectural style emanating from his time, but connected to history. When that time comes, we shall probably be able to judge and find the best way to treat our monuments: now I ask for a truce with the restorers and ask them whether it would not be better for them to be prudent and patient in their decisions until that time comes; in the meantime to carefully repair the treasures of art and protect them from infiltration"4.

Common sense and dogma

In short, for two centuries now, the West has been working intensively to produce solutions to protect the architecture of the past. For the sake of people, who seem to be increasingly in need of a stable, organic materiality and memories on which to rest their minds, worn out by so much modernism, communication and cyberspace. "We can live without architecture, but without it we cannot remember"5, said John Ruskin in The Lamp of the Memory. Today we are not too far removed from the romantic attitude of Ruskin and Morris, who were driven by the galloping effects of industrialization into the past, into the vernacular, back to nature and nostalgic utopias. (The word nostalgic has no negative connotations.) Notions like historic monument, heritage, environment, exert a greater spell today than ever before. Everyone agrees that the architecture of memories must be preserved, because it is of fundamental importance in maintaining a psychological continuum on the axis of time.

Arguments start when, in putting things into practice, the measure of things is lost, either through the erosion of common sense or intellectual opacities. Deviations appear in the form of exaggerated behavior and inappropriate interpretations. This is why, over the last two centuries, 'restorationists' have formulated a series of systems of thought, methods and procedures, which they have made more and more flexible in line with the complexity of situations. We have a whole history of the evolution of these ideas and work is continually being done to update them. We master a lot of cultural, historical and aesthetic criteria for evaluation and categorization. We have research and disciplines, we have scientific as well as heuristic approaches; we have affective interpretations, philosophies and literary pleadings, we have hierarchies and methodologies, axiological classifications and epistemological systematizations, we have international conventions, theories and allegories. We have, of course, legitimate aporias, paradoxes, contradictions and 'binaries', as Plato would say. With such formidable theoretical tools, and after such an investment of intelligence and passion, one would think that the relationship between our built space and the past would function in heavenly harmony. But it does not. And we are not talking here about vandals or Taliban.

We're still talking about the common-sense pandant: over-cerebral over-theorizing. Perhaps over-theorizing leads secondary spirits to erode intuition. What else is dogmatization but a departure from the right multicriterial weighing in favor of the absolutization of a single-point of flight perspective. The history of the great cultic radicalizations begins with adherents of Ruskin and Viollet-le-Duc, who applied their antagonistic theories pushed to extremes. It continues with the modernist whirlwind and culminates in the inexplicable demolitions of the 1960s-806. Faced with the complex and fluid reality of the last centuries, it was not the unknowing mobs, but the good intentions of restorers and the heated convictions of architects that produced both the exaggerated "museifications" and the two types of cultic vandalism, called in the 19th century destructive and restorative. The destructive type gave way to the new urbanism of the industrial age. As for the restorative type - a kind of constructive destroyer, one historian of the time argued that "the merit of the wreckers is that at least they restore nothing". (He was a moderate non-interventionist.)7

One can also talk for a week about uninspired interpretations of the legislation, in other words about the distorted relationship between the evaluation-classification reference system and the type of intervention applied. It is true, for example, that the addition must be distinguished from the original, but not every shed must be filled with glass. It should not be forgotten that common sense, when it exists, is not only a quality of the innocent, but also of the initiated.

The functional mechanics designed to apply recommendations came to be exercised after the institutionalization of monument protection, i.e. after the advent of legislation and commissions at the beginning of the 19th century8. The officials were not too concerned that misunderstood impositions could fuel the concealments and rebellions of the beneficiaries and even of the designers. And then vice versa. The particular rebellious reactions lead to new restrictions and dogmatic indications, applied to superficially evaluated situations, ignoring the particularities9. An allez-retour with increasingly aberrant effects. On the subject of corruption, we are not talking at all.

So the legislation and recommendations are of a general nature, leaving room for specific interpretations. What is the right way between the danger of legislative dogmatism and that of individual arbitrariness, I do not know, especially in a country like ours, where the economy dictates almost unrestrainedly and politics has the last word. Perhaps it would be better to follow William Morris's example in the meantime, i.e. to wait until we grow up. But in the meantime, let us conserve!

Conservation-restoration and revitalization-modernization

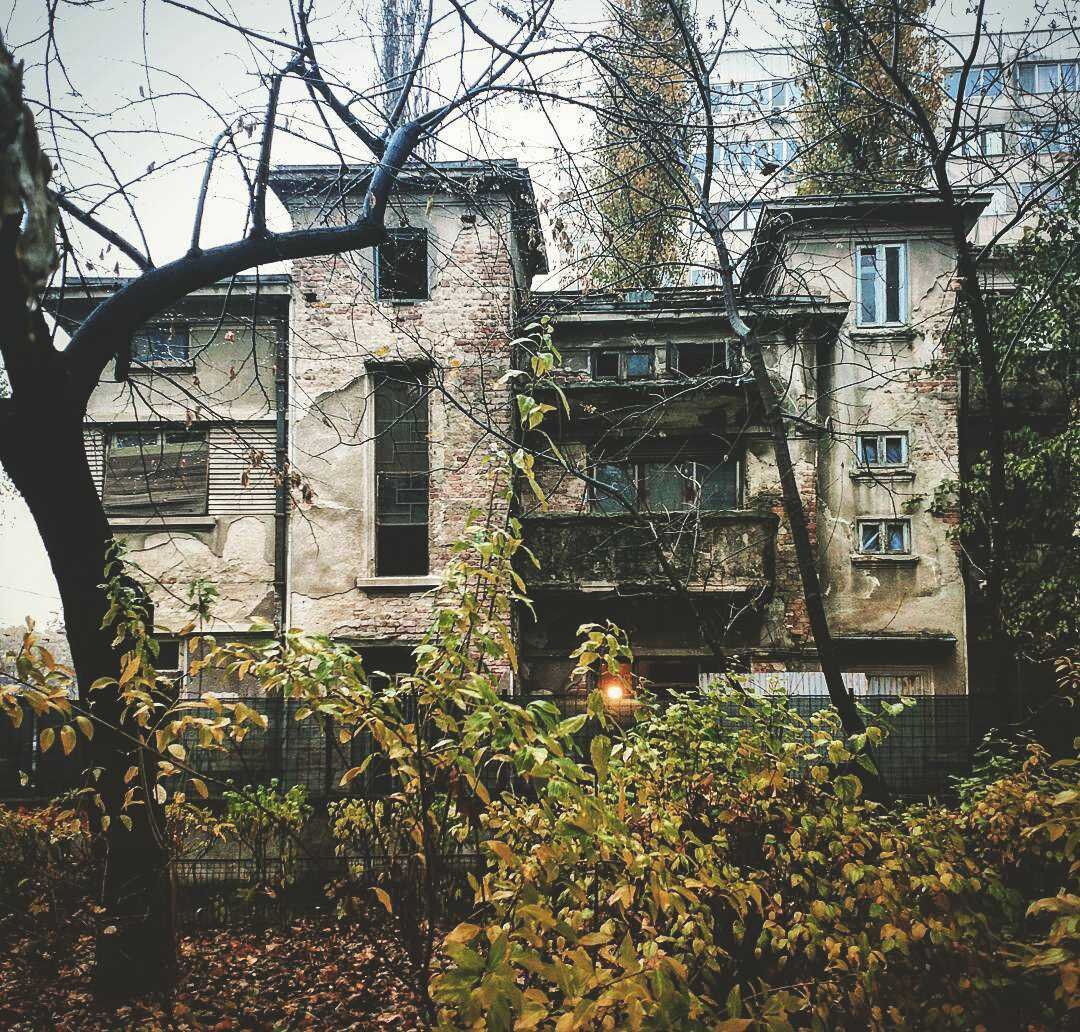

The gentle Hendrik van Loon deplored the loss of some of Michelangelo's masterpieces due to the unconscionable negligence of his nephew who had inherited them. However, with timidity and prudence, he also reflected that such unfortunate events, like natural catastrophes, still help to prevent the earth from becoming a repository for antiquarian antiquities.

He was then a singular voice. Later, however, the panic about heritage inflation spread. If, in Viollet-le-Duc's time, only temples and churches, castles and palaces were, in principle, protected, in any case, not having passed the Age of Enlightenment, over time the criteria for admitting architecture to protection have broadened and diversified. Heritage encompasses new programs, even the most prosaic. Ruskin derided those who "fancied themselves philosophers, substituting the worship of the goddess Vesta for the worship of coal gas". (Someone even said at the time: "Gas stations are the cathedrals of our times"). But after almost two centuries, both the stations and some of the buildings that used to produce coal gas have become monuments to heroic times and stir our emotions. It is therefore worth preserving them.

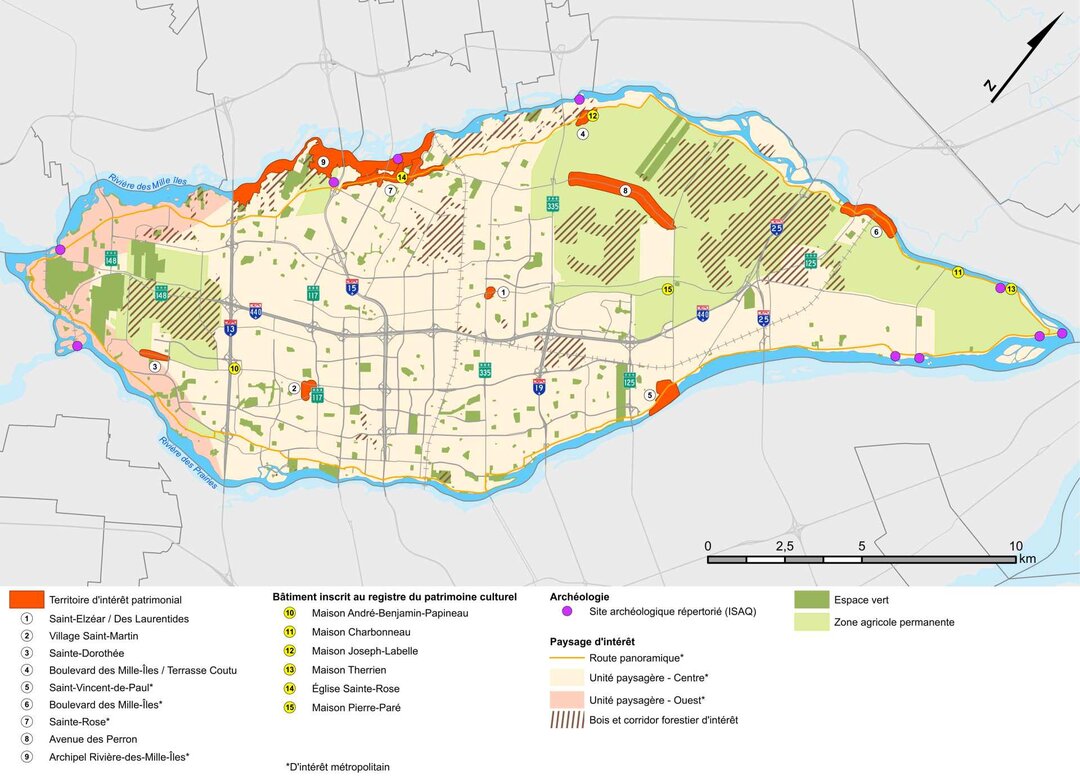

Then, since the Venice Charter accepted the concepts of site and integration, protected areas have also grown in size, sometimes encompassing entire localities. The time axis has also expanded. Docomomo protects monuments of modernism. Some pavilions at the Shanghai Expo 2010 will remain permanent and will probably come under protection. On the other hand, the concern for world heritage goes to the margins of the world, to peripheral cultures, perhaps even tribes - specialists in authenticity. The axiological scope has also expanded, from the value of a listed monument to environmental value. And if things continue, there is fear that there will be no room left for development and all architects will become restorers. Now, this honorable field of restorations doesn't really consecrate VIPs. It's like translators. Everyone recognizes their work, but the glory still goes to the ontic act of creation.

William Morris recommended that old monuments should be preserved and left alone, while the new should be new and mark the present. He was right, of course, no one is going to restore the Colosseum or Stonehenge, and mimetic reconstructions are rare and applied in special cases. But in marking the present, modernism has gone too far. It has built a wall to the sky between restoration and the architecture of the present. Keep the Nôtre Dame and the Louvre, pass them by, but shave the rest to make way for modern life. No gray tint between restoration, demolition and new architecture. Destroy to build - bliss on developers! Except that since then, people have been alienating themselves from the present and seeking refuge in the past.

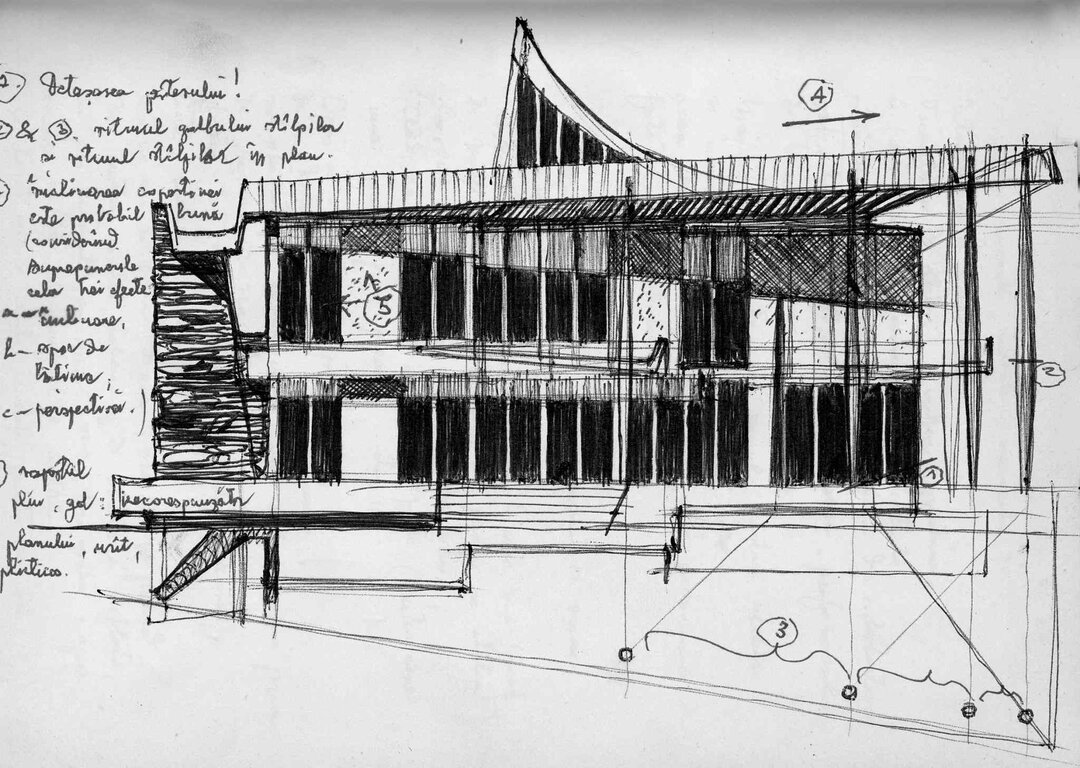

In the late 1980s, a chorus of authoritative voices argued for a new form of interventionism, different from that of Viollet-le-Duc, to save history. They remembered the revivals of the last century: of Schinkel, who had said around 1810 that "historicism does not mean repeating old architecture, because that would destroy history. To design in a historically related manner is to introduce something new, which at the same time continues history"; by Ruskin, who loved Gothic because he had not forged (compositional) canons to prevent additions, thus allowing architecture to evolve and participate in life. The traces of interventions over time on a cathedral can be seen from right to left, as no two towers are the same, and successive styles are placed vertically, from plinth to roof, he said. He also said that "a building is a component of a great system in perpetual transformation"10. Then the Athens Charter allowed the use of modern materials in restoration, and the Venice Charter allowed some monuments to be supplemented where necessary. And then there was Scarpa at Castelvecchio.

Supported by such solid references, came liberalization, which introduced the missing link between scientific restoration and demolition, in the form of transformations-modernizations, especially of "minor" architecture, such as industrial architecture. In addition, conversions and modernizations - even of a Romanesque abbey turned college - gave more work to architects than to restorers, who were in the minority anyway. The solution pleased those with avant-garde impulses in their breasts, who for years had been embarrassed by restorers at every turn. Those with conservative sentiments still bombast about the callous voluntarism of ADHD-afflicted architects, but they also recognize that the right of each generation to imprint the urban space should not be repressed. Otherwise, repression, as Freud said, you wonder where it can lead. And architects with no appetite for antiquarianism are still complaining about monument commissions. It's clear that heaven on earth doesn't exist.

From insertions and conversions to Françoise Choay's Heideggerian-argued and also allegorically expressed solution of erasing the dividing line between new architecture and the treatment of monuments, there was another step. She called it the "demonetization of heritage" and insisted on regaining "our competence to build". We can design new buildings with the same sensitivity as restoring old ones (with care for context, for example), and we can safeguard heritage by resurrecting it through reinterpretation and resemanticization.11 We are thus rewriting history and loading it with the best the present has to offer. The thesis was launched 26 years ago.

A friend was telling me that the other day, after one of his presentations of a similar thesis at a scientific seminar, he was about to be lynched.

Culture and money

Still. We could manage among ourselves with all our contradictory oppositions, paradoxes and binary contradictions, if we didn't have to come down to earth from our rarefied heights to answer to accountants and mayors. They are the two hedge hedgehogs in the game with the dwarves, that is to say, the willful architects and restorers, with their helpers, historians, artists, philosophers... Only Hegel - à propos - instead of repenting us, sent us to the queue on precisely this account.

I have suspected a certain naiveté on the part of the architects who have embarked on Ruskin and Françoise Choay's ark of involving historical architecture in our present life, believing that this movement is deeply cultural. In reality, it was made possible because it is cost-effective. Their speeches and allegories are nice, but they would have remained esoteric academic concoctions if the refurbishments didn't recoup their investments and the historic centers didn't bring tourists.

Nor would it have been possible for the restorations-modernizations to have any other destiny than current architecture. Both are caught in the middle, between their noble purpose of creating cultural values on the one hand and the obligation to create economic added value on the other. They also have to respond to political guidelines that invoke the social interest. The binary values have become three.

So the dwarves fight in the name of cultural value, the hedgehogs in the name of economic value and social value. And we have seen that, in this game, the dwarves and the hedgehogs win. So, in passing, one value dominates the others.

All architects have had this experience, namely that, as a rule, the arguments for success against non-professionals are objective ones, and the quantifiable ones prevail. Rarely do we find anyone receptive to our abstract explanations of psychological comfort, feelings, spatial sensations or even social interest (from our perspective). Then, in most cases, economic value is the winner.

But historic centers and insertions, with their meanings, warm the present and provoke emotions, involving a collective complicity among the audience. Their success has social value and is due to their cultural value. Which success can also be counted in money.

In conclusion, beyond the theoretical versions, historical architecture is nowadays the most marvelous happening in architecture. With the exception of grumblers, it gathers around it people, facts and values, dwarves and hedgehogs, architects, restorers and the public, economists, mayors and tourists, the goat and the cabbage.

So there's always a ray of paradise on earth.

A fleeting glimpse.

NOTES

1 "The results of the investigations made by Herodotus of Halicarnassus are here presented. Their purpose is not to let time efface the traces of the events of mankind, to preserve the fame of the remarkable achievements of Greeks and non-Greeks...", he announces at the beginning of the Histories.

2 Augustus Pugin, Contrasts: or a parallel between the noble edifices of the middle ages, and corresponding buildins of the present days; shewing the present decay of taste.

3 William Morris, News from Nowhere.

4 His hope of an architecture that would satisfy the aspirations of all, linking the past with the future through the present, seems more remote today than ever, comments Peter Davey in AR 1166.

5 Translated by Kázmér Kovács, from a quotation by Françoise Choay in The Allegory of Heritage, 1998.

6 The Schocken shop in Stuttgart, the halls in Paris, the Großes Schauspielhaus (Friedrichstadtpalast) in Berlin and others. Those in socialist countries have specific explanations.

7 Françoise Choay, L'Alegorie du patrimoine, 1992.

8 The path of modern institutionalization after the Renaissance opened up during the French Revolution.

9 "Every case is a different case and for each we have to define our approach". The UNESCO 1972 World Heritage Convention.

10 Peter Davey, in AR 1166.

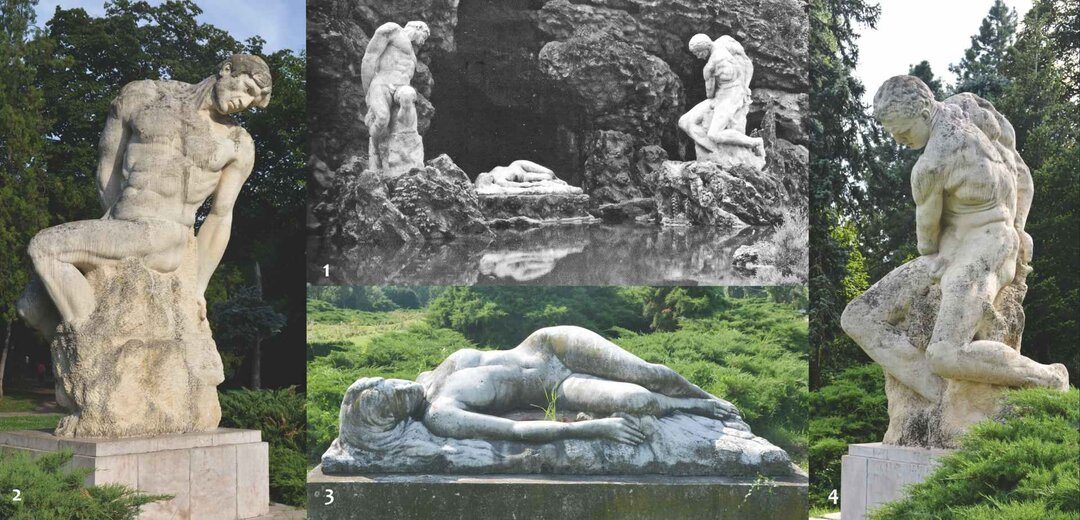

11 In L'Alegorie du patrimoine, Françoise Choay portrays the "competence to build" as a hypostasis of being, like the competence of speech or of dwelling. She likens the museified heritage to a mirror in which its worshippers contemplate themselves like Narcissus. But this worship led Narcissus to his death. See also Kázmér Kovács, Narcissus' Mirror, in Arhitectura 3-4/2001.