The frail life of Bucharest monuments

text: Alexandru PANAITESCU

A retrospective glimpse at the situation of public monuments in Bucharest over the past 100 years reveals an uncanny reality most often defined by uncertainty and/or improvisation. This is generally due to a pair of reasons acting separately or jointly, depending on the case. First, it is the sometimes brutal influence and discretionary manifestation of politics, not only in the case of authoritarian or totalitarian governments but also when it comes to those allegedly democratic, which radically come forward in times of political regime change and profoundly affect the recent evolution of the Romanian society. On the other hand, most often than not, the precarious location of some monuments is also the result of the vague urban development solutions for representative public spaces in Bucharest which all lack a coherently defined configuration and are not prepared to appropriately incorporate important monuments.

A prefiguration of the brutal attitude towards monuments and of their frequently insecure position was represented by the extremely brief existence of the first public statue in Bucharest – the statue of Liberty or „Liberated Romania” by Constantin Daniel Rosenthal (1820-1851), inaugurated on 23rd June 1848, a reflection of the revolutionary spirit of the time. Less than a week after installation, the statue was to be destroyed on 28th June, under the orders of Conservatory Governor Emanoil Băleanu, a supporter of the political regime imposed through the Organic Rule. Faithful to the spirit of the age, the patriotic-revolutionary theme embodied by the statue was allegorically rendered by a woman dressed in a toga and wearing a laurel wreath on her head; the chains binding her were broken and she was holding a cross in one hand and the scales of justice in the other. A painting illustrating the same theme, destroyed at the same time as the statue, was placed on the pedestal. We thus witnessed “a first example in the sequence of acts of vandalism leading to the destruction of statues and monuments across Romania. Similar gestures will be encountered in one hundred years’ time in a similar context of political overthrow”2.

From the last quarter of the 19th century indicating the beginning of a period defined by efforts to modernize the centre of the capital until the start of the Second World War, special attention was paid to the construction of public monuments, both on the initiative of the authorities and the civil society, with funds gathered through public collection by specially constituted initiative committees. The monuments paid homage to emblematic historical figures, such as Michael the Brave (1876, sculptor Carrier Belleuse)3 but also political leaders who played a decisive role in the modernization of Romania. Many of the statues depicting the latter had a conjectural existence influenced by political changes and their cases are presented in the following.

Although certain questionable urban planning actions affected the location of some monuments in Bucharest prior to 1940, it is in 1948 that the most difficult moment in their existence was to take place, when the communist regime, fully in power after the abolition of monarchy, initiated an aggressive campaign of destroying the statues of historical leaders regarded as politically undesirable. Without exception, these were valuable works of art designating key landmarks in Bucharest.

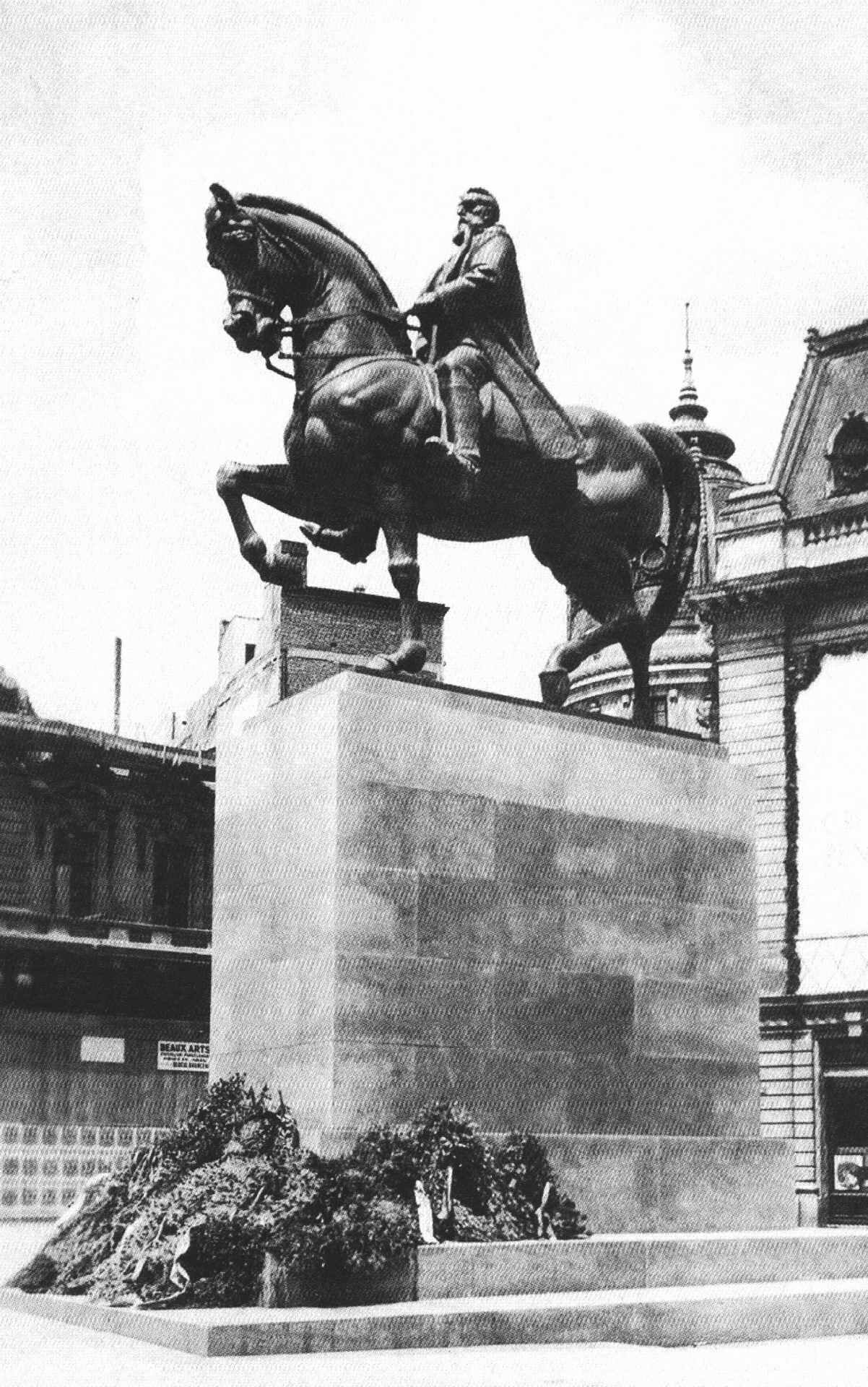

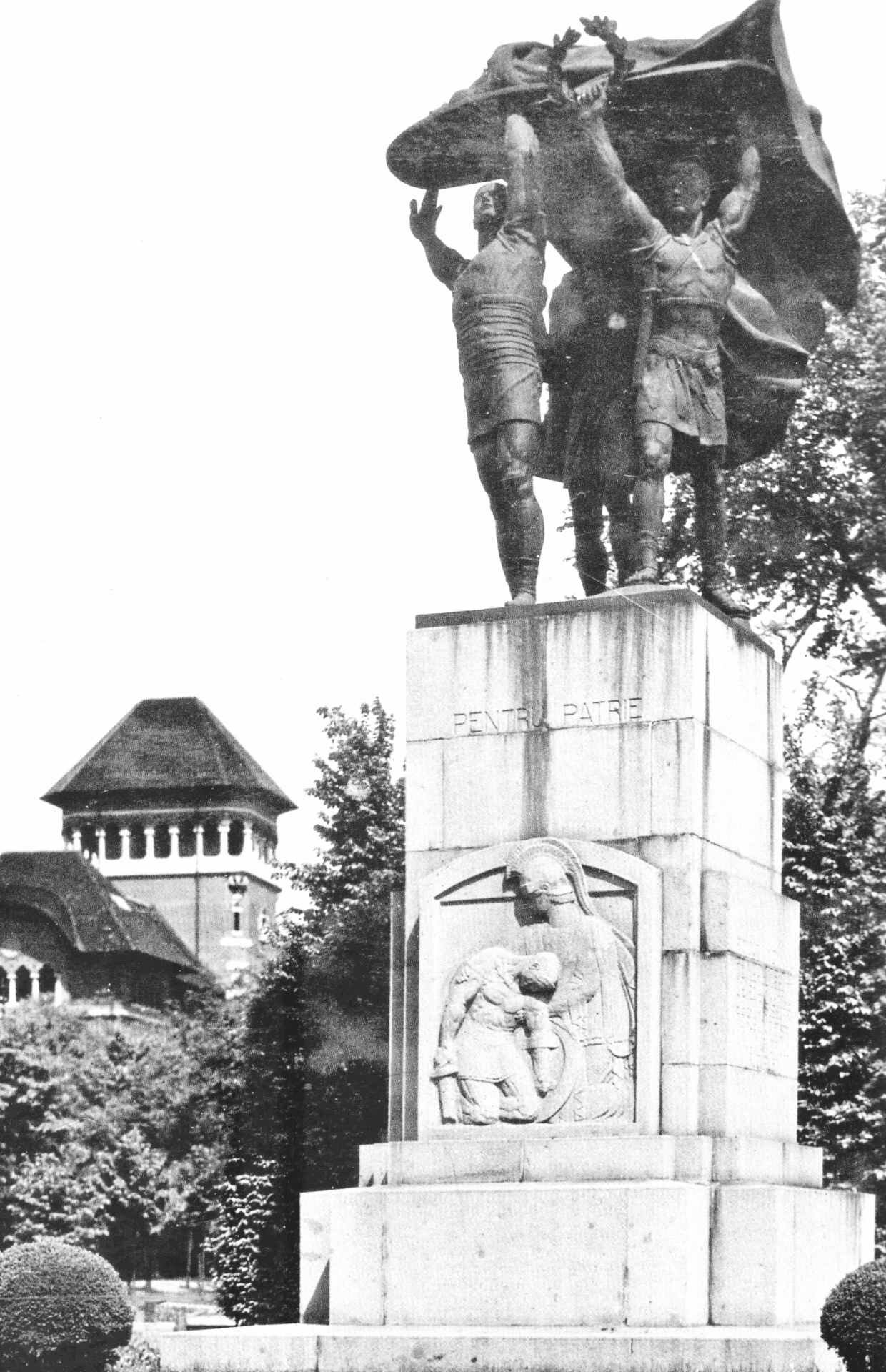

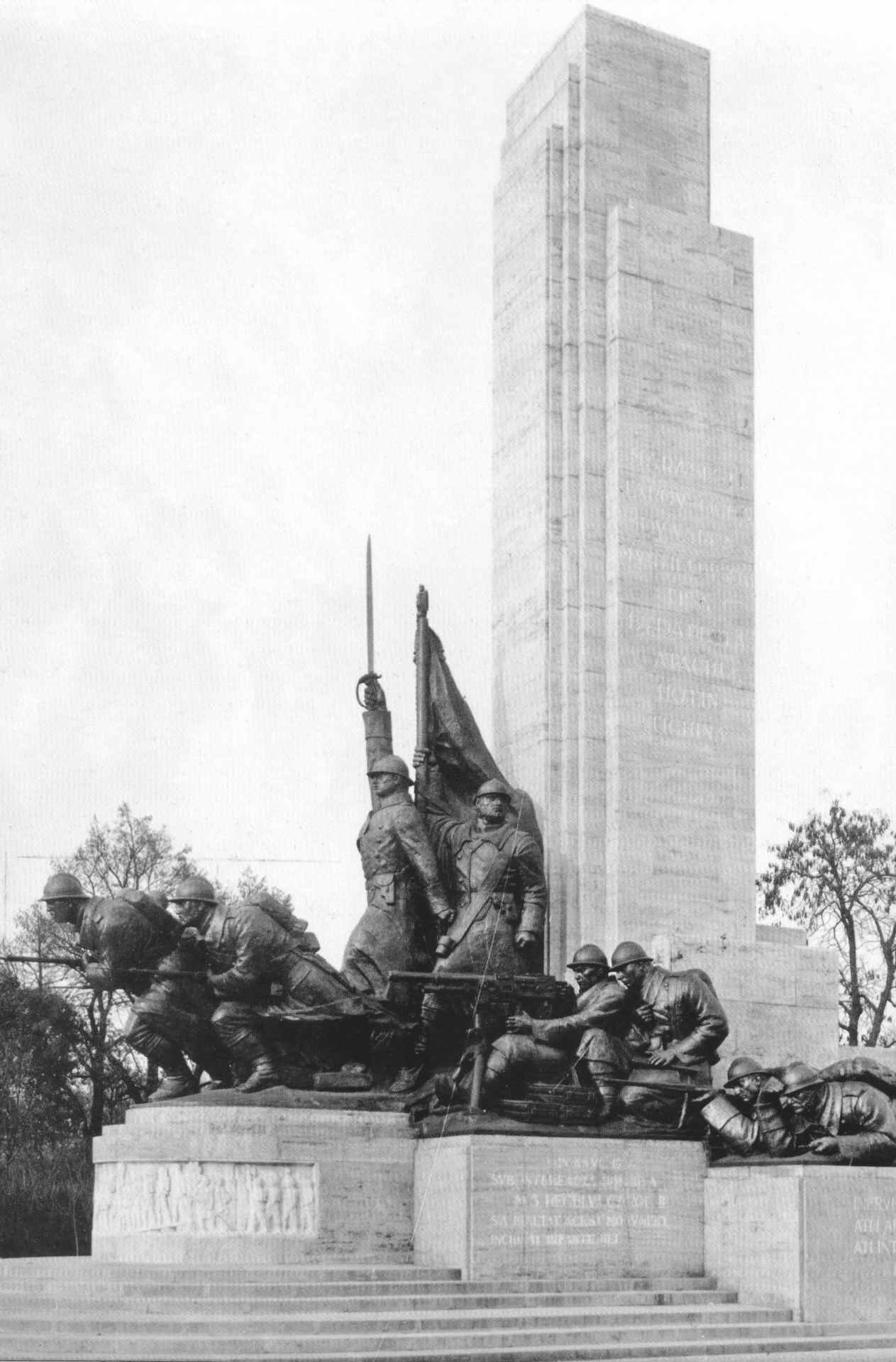

First of all, it was the monument depicting Ion C. Brătianu, located in University Square (1903, sculptor Ernest-Henri Dubois, with the pedestal designed by architect Petre Antonescu)4, as well as the two short-lived works belonging to Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović: the equestrian statue of King Carol I in front of the Royal Palace (1939) and the portly monuments dedicated to King Ferdinand I (1940), consisting of an equestrian statue flanked by four red granite pillars, each bearing an allegorical statue of Victory and erected on the western part of the first square on Kiseleff Avenue.

In 1935-1936, when the monument was restored with cut-stone veneer brought from Turcoaia, Câmpulung, Bașchioi, Bamporoc and Rușchița, the decoration became milder, the Neo-Romanian influence was simplified and modernized and the impressive statuary groups were removed. The main sculpture elements are the medallions depicting the royal insignia (sculptor Alexandru Călinescu) placed on the southern side of the monument as well as four bas-relieves portraying symbolical representations of Victory (sculptors Constantin Baraschi, Mac Constantinescu, Cornel Medrea and Dimitrie Onofrei), two on each side of the Arch as well as medallions depicting Faith (sculptor Constantin Baraschi) and Manhood (sculptor Ion Jalea), on the northern side. The other sculpted ornaments are fairly discrete and tributary to an austere and highly imposing architectural concept. In its final version, the Arch of Triumph has a 27-metre high cornice, a 25-metre wide front base and an 11,5-metre wide side base while the central vault has a 9,5-metre opening and a 16-metre height. In 1992, following a very awkward attempt of restoring the initial version, bronze replicas of the medallions portraying the two sovereigns were placed on the Arch of Triumph. During the extensive restoration works carried out in 2014-2016, the royal effigies were reproduced in stone and all the parts destroyed in the communist period were restored; even the panels containing the proclamations of King Ferdinand, situated on the laterals of the monument, were recreated.

Ivan Meštrović is also the author of the black granite statue of Ionel I. C. Brătianu (1938), disassembled in 1948. Fortunately, it survived the communist period with minimal damage, being initially cast away in the park of Mogoșoaia Palace and then carefully preserved in the garden of the museum in Golești, Argeș. In 1991, the statue was located in the same spot on Dacia Avenue, in the square behind Brătianu Institute. To make room for it, they demolished a modest bronze bust (sculpted by Nestor Culluri7) portraying Ilie Pintilie - a clandestine leader of the Romanian Communist Party who died at Doftana during the 1940 earthquake - which had occupied the place of the statue of I. I. C. Brătianu during the communist period.

At the end of the 1940s, they also destroyed the bust of Eugeniu Carada8 (1924, sculptor Ernest-Henri Dubois), found near the National Bank, at the corner of Lipscani and Eugeniu Carada Streets. In 2013, over six decades and a half after its destruction, it was rebuilt in a fairly simplified form, quasi-similar to the original (sculptor Ioan Bolborea).

Likewise, in the same period at the dawn of the communist regime, they demolished the bronze statue of Emanoil Pache Protopopescu9 (1895, sculptor Ion Georgescu), located on the homonymous avenue, in a square in the vicinity of Grecești Church. A water fountain was set up in the place of the statue of Pache Protopopescu until 2007, when it was uninspiringly replaced with the three-quarter statue of Nicolae Bălcescu (sculptor Mircea Spătaru), probably in order to complement an axis of the 1848 generation initiated with the statue of Mihail Kogălniceanu (1936, sculptor Oscar Han) in the homonymous square and corresponding to the statue of C. A. Rosetti (1902, Wladimir Hegel) yet lacking the main piece, the monument of Ion C. Brătianu, situated in University Square.

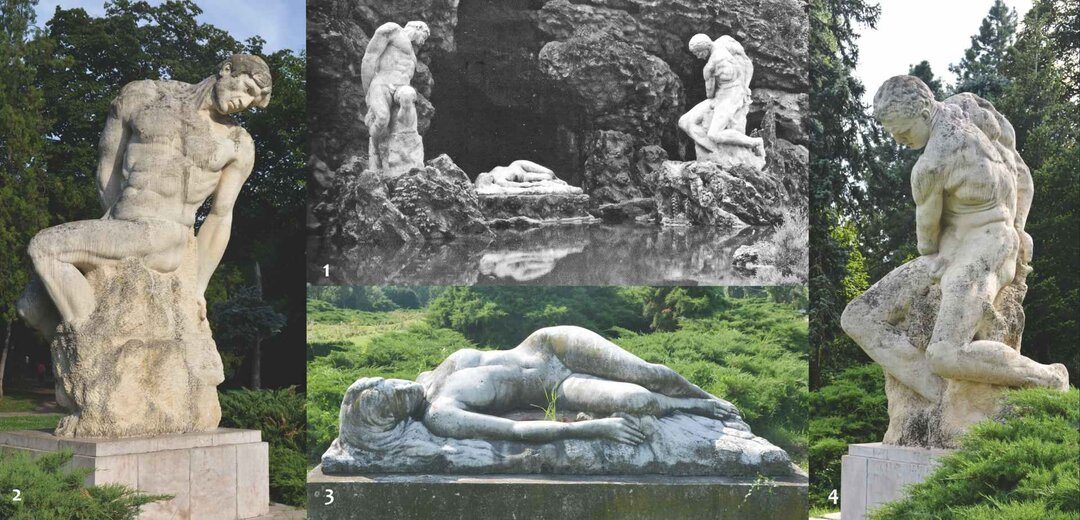

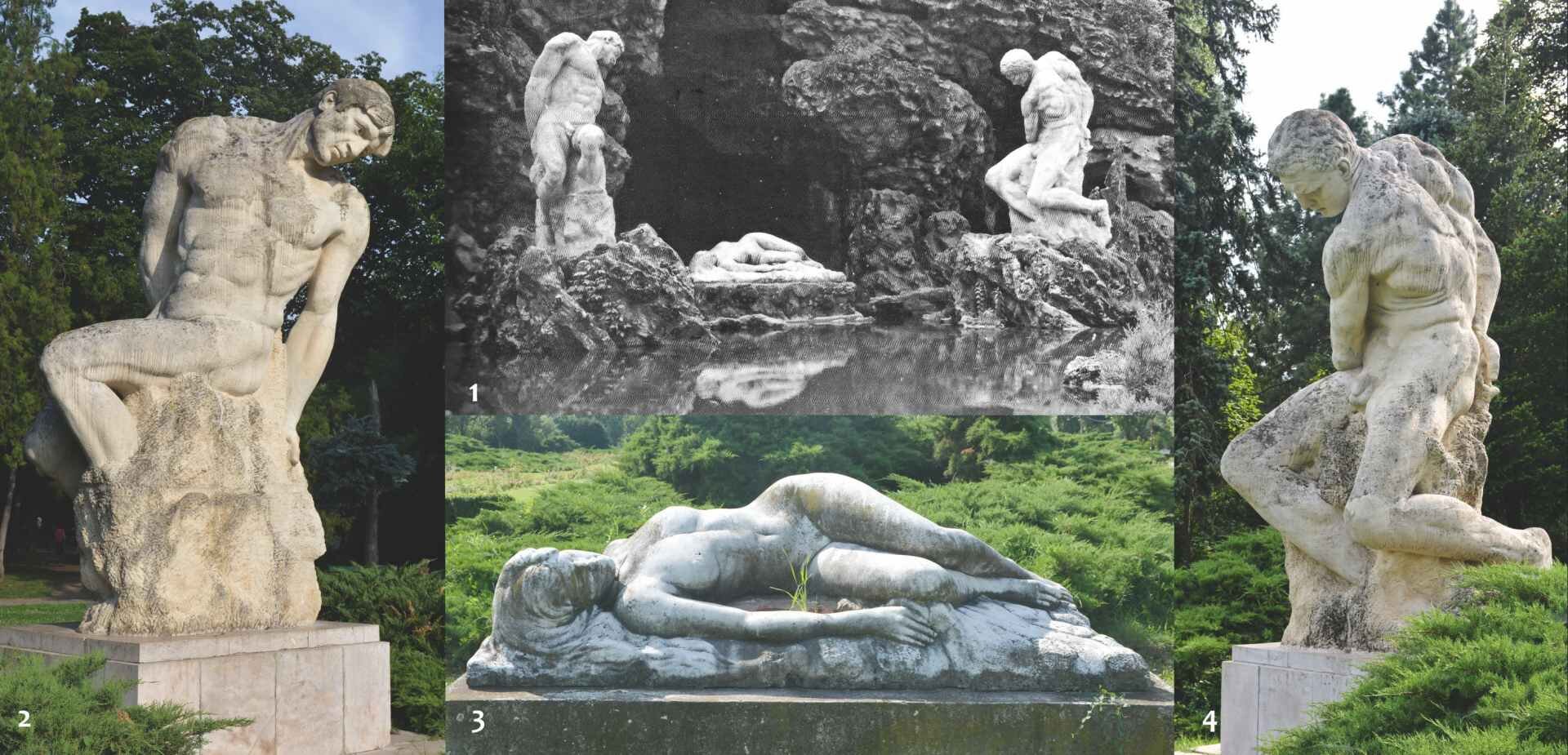

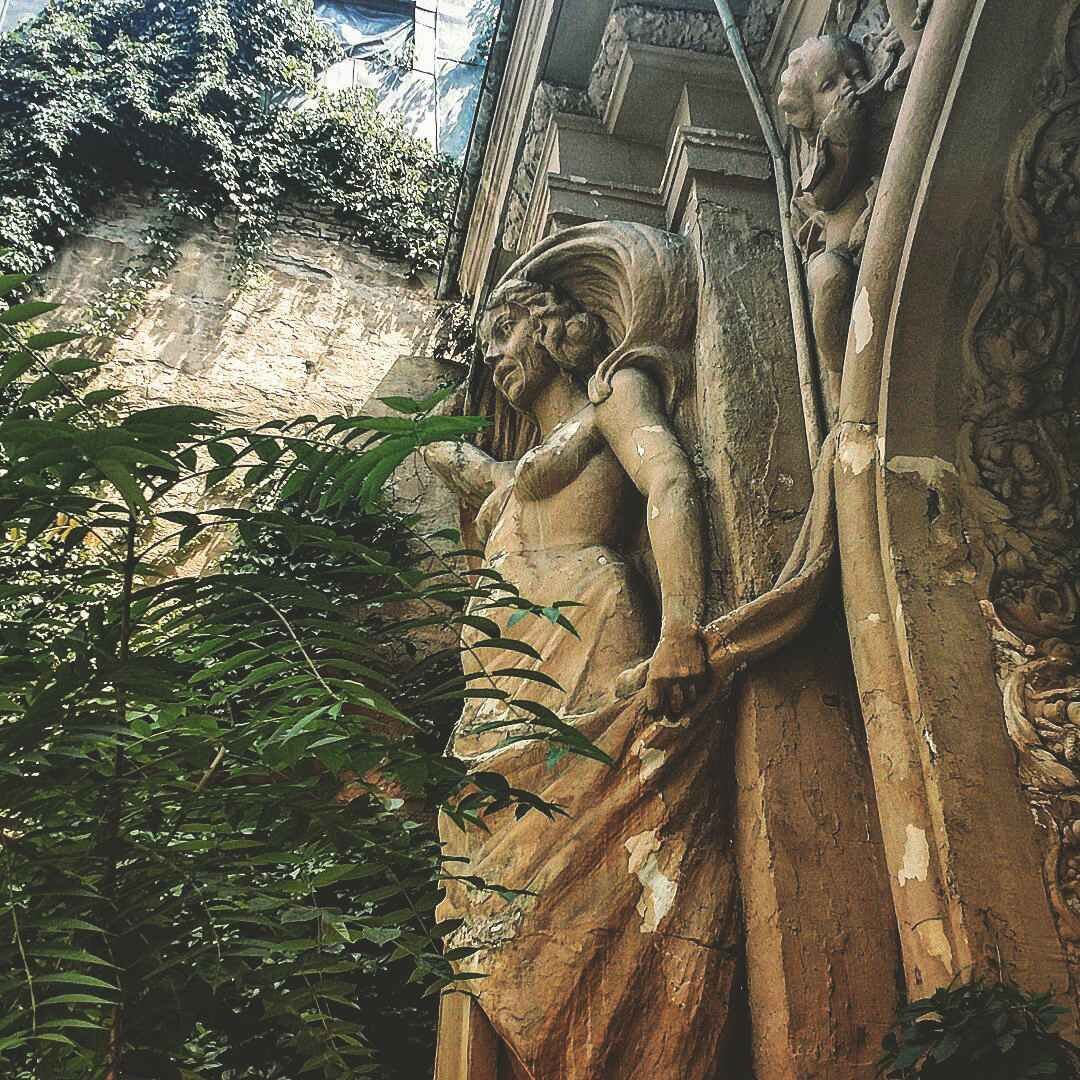

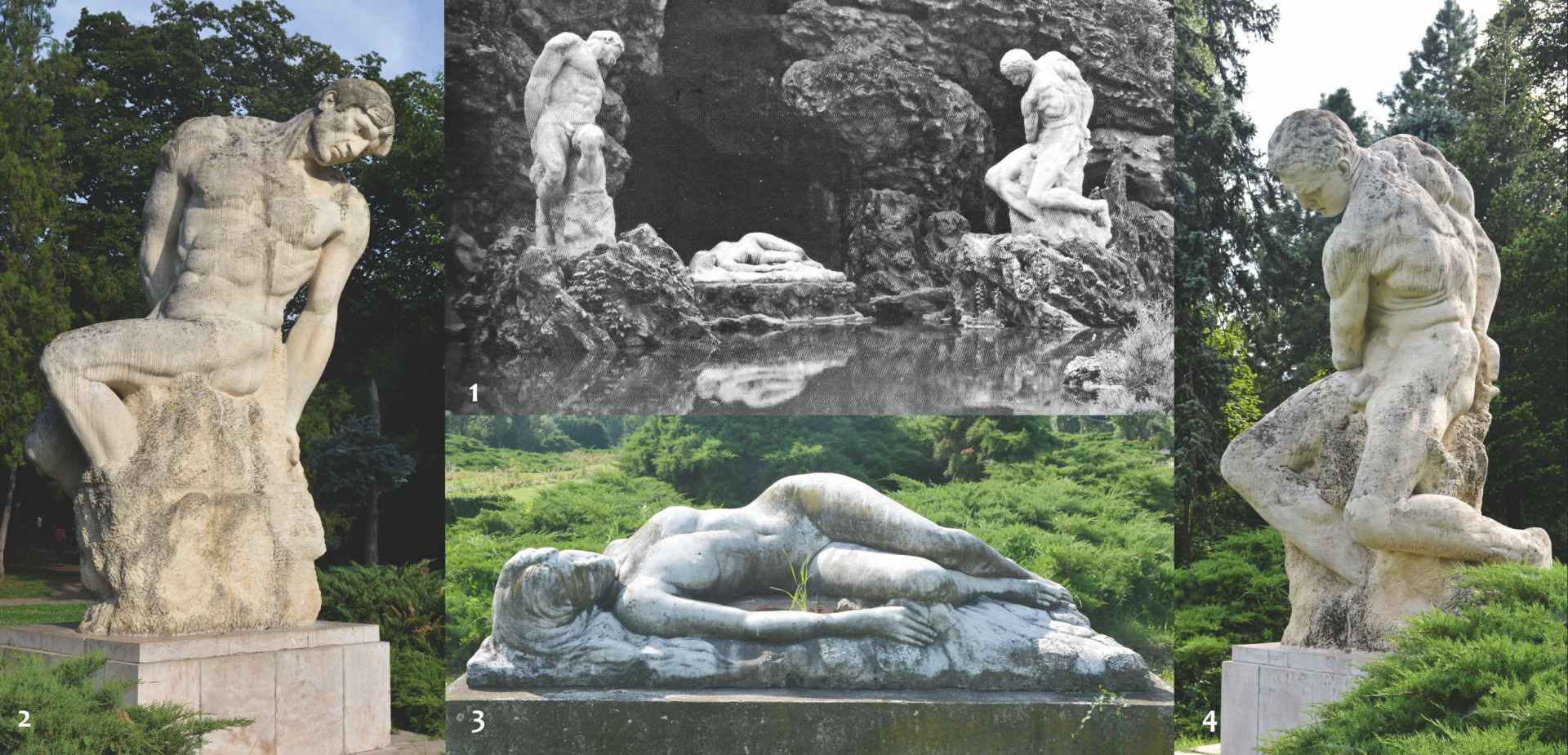

In 1958, with a view to building the pantheon of communist leaders (completed in 1963, architects Horia Maicu and Nicolae Cucu) in Carol Park (formerly called Liberty Park), they demolished the Giants’ Grotto - an illustration of the legend „The Pines” in the volume The Story of Peleș by Carmen Sylva (Queen Elisabeth of Romania) - a monument set up on the occasion of the 1906 Jubilee Exhibition. It was situated at the bottom of the cornice where there was the former Military Museum, originally The Palace of the Arts (1906, architects Victor Ștefănescu and Ștefan Burcuș), demolished at the beginning of the 1940s as a result of a fire. The concept of the statuary ensemble in the grotto belonged to Dimitrie Paciurea, Frederic Storck (the giants) and Filip Marin (the nymph). Following the destruction of the grotto, the giants were relocated in 1963 on the main park alley while the nymph was later placed in Herăstrău Park after a possible stopover in Tineretului Park (The Valley of Tears).

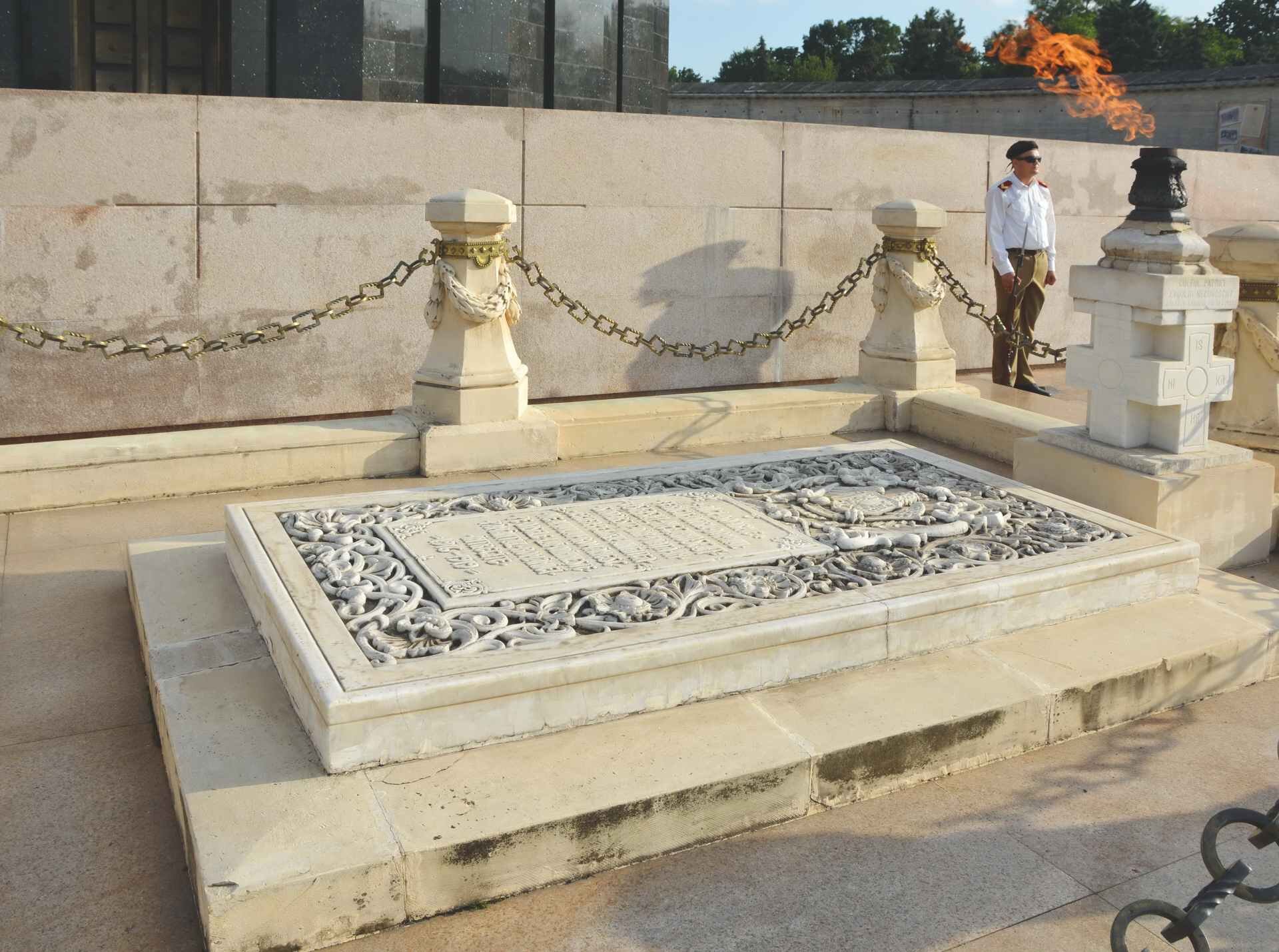

The same year, 1958, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier set up in 1923 on the platform above the grotto was secretly moved to Mărășești. It returned to Carol Park in 1991, when it was inappropriately located at the park entrance; it was only in 2006 that it was moved to its initial place.

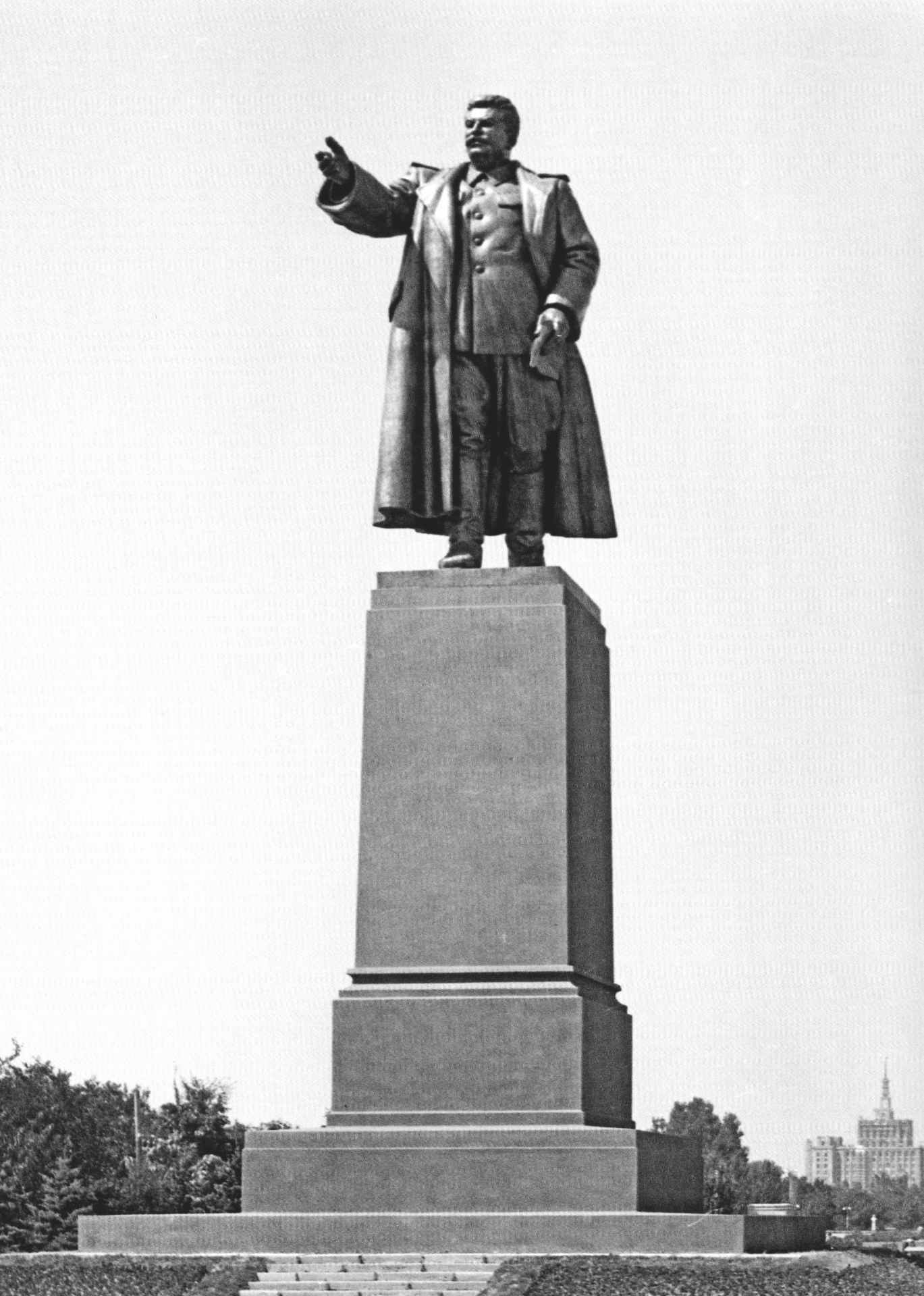

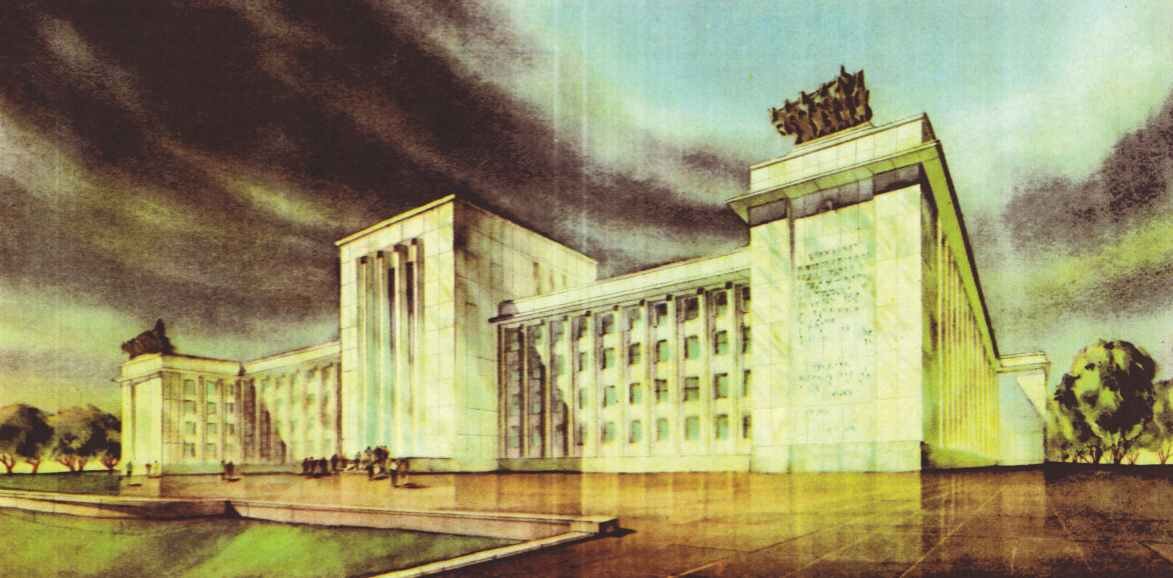

The nine-metre tall monument of V. I. Stalin (inaugurated in 1960, sculptor Boris Caragea) with a 6,15-metre high statue located on the esplanade facing the Free Press House (the pedestal and the site planning were the work of architects Horia Maicu, Nicolae Cucu and Iulian Nămescu) was demolished, in the postrevolutionary turmoil, in the spring of 1990 and deposited for a long time in the park of Mogoșoaia Palace, then in the courtyard of a storehouse near Toboc-Petricani Farm, in the vicinity of Plumbuita Lake. In the 1990s, the statue pedestal was subject to several competitions or attempts to find a creative purpose, many of which were fictionally ironic.

. In the end, the initiative of the Association of Former Political Detainees in Romania materialized and, following a competition held in 1999, the monument „Wings” (inaugurated on 30th May 2016, sculptor Mihai Buculei) dedicated to the anti-communist resistance came into being. Well-proportioned in relation to the surrounding urban space, the 20-metre high monument comprises three towering wings made of matte stainless steel depicting an artistically fulfilled model.

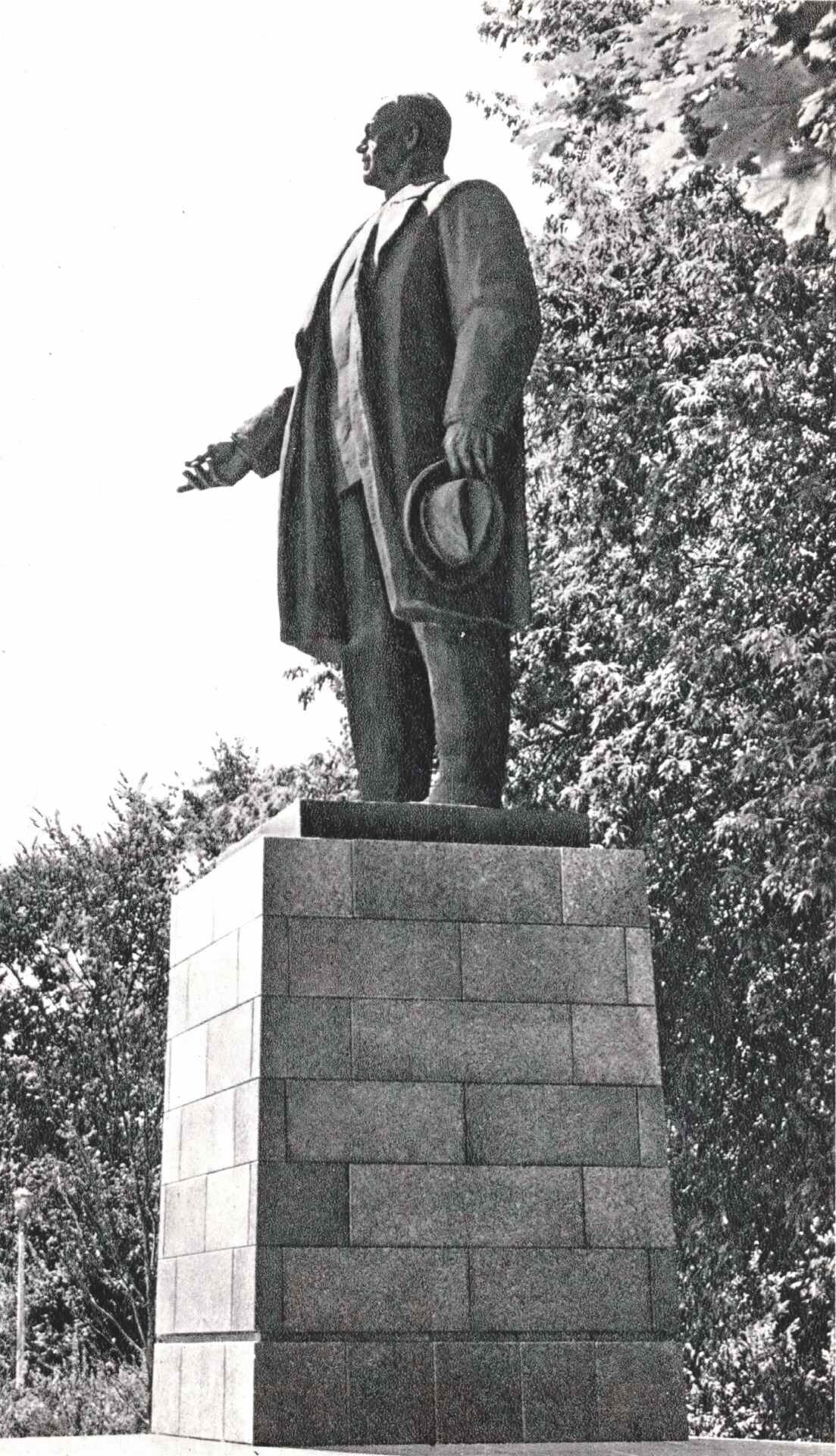

A similar destiny with Lenin’s statue was shared by the monument dedicated to Petru Groza (inaugurated in 1970, sculptor Romul Ladea), found at the intersection of Heroes and Sanitary Heroes Avenues until 1990. The Artillery Memorial was inaugurated on 10th November 1993, on the former location of the statue portraying Petru Groza; executed in bronze by sculptor Teodor Zamfirescu, the work displays an ambiguous modernity and questionable symbolics.

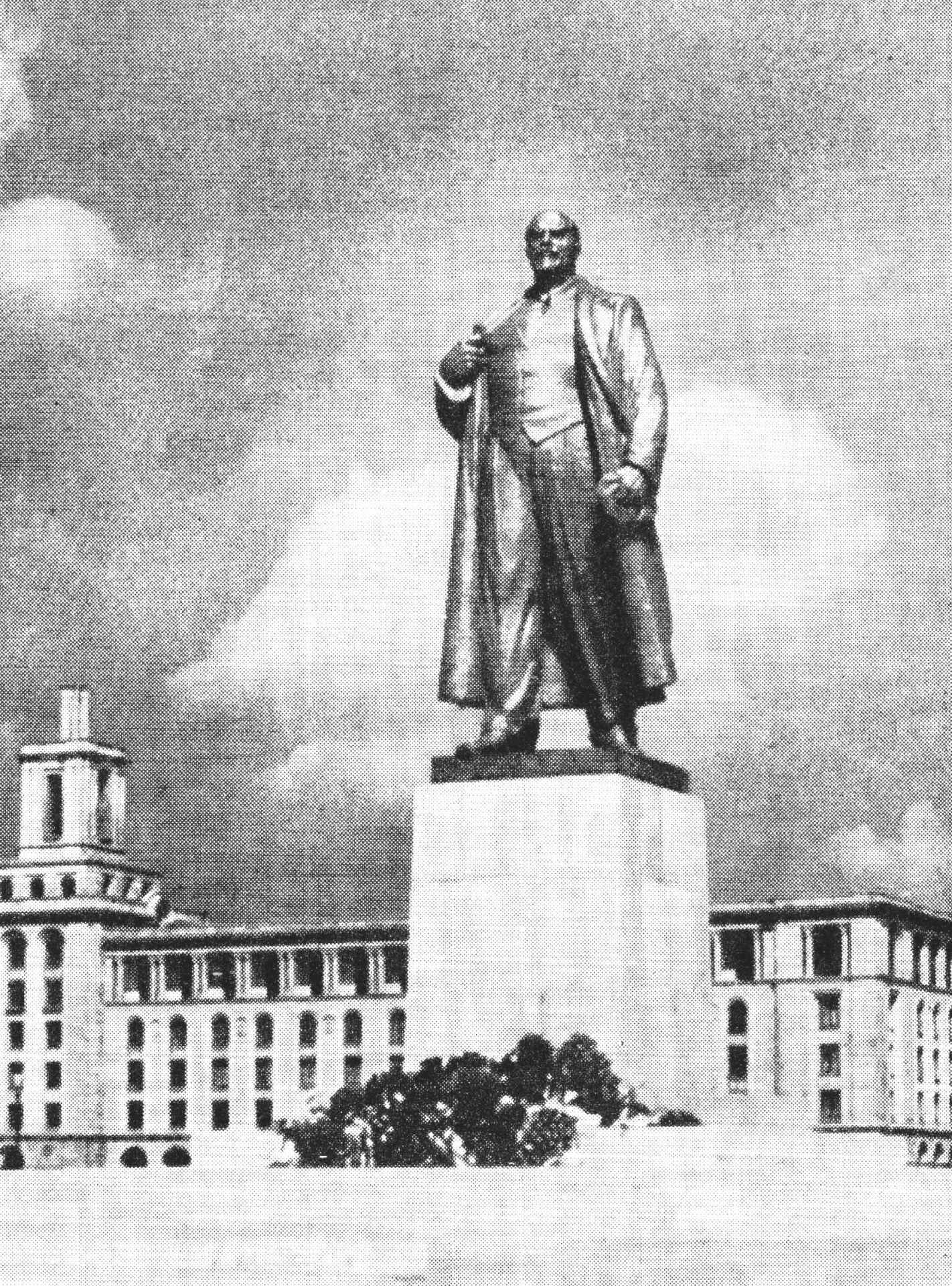

This tortuous path was also shared by the Monument to the Soviet Soldier (1945, sculptor Constantin Baraschi, with a pedestal designed by architect Mihai Ricci), originally located in Victory Square, between Kiseleff and Aviators’ Avenues, on the site vacanted by the dismantling of the Monument to Educators in 1940. In the mid-1980s, during the works for the Victory Square underground station, as a tardy manifestation of the de-Sovietization process and under the orders of Nicolae Ceaușescu, the monument was moved near the first square on Kiseleff Avenue14, on the former site of the Monument dedicated to King Ferdinand and later relocated in the Soviet Military Cemetery on Pipera Road, but on a much smaller pedestal than the 12-metre tall original one.

Although these elements symbolize the years of communist dictatorship and their questionable artistic expression reflects the social realist style, they are still part of a history that must not be forgotten and their display would have prevented this oblivion.

At the end of the 1970s, a correct approach was taken with regard to the Monument to the Sanitary Heroes (1932, sculptor Raffaello Romanelli, architect Statie Ciortan) found in the Opera Square, at the intersection of Sanitary Heroes and Independence Avenues. The monument had to be disassembled because of the works for the underground station in the area; after their completion in 1979, it was immediately remade under the careful supervision of architect Ioan Novițchi. Given the political context of the time, it is paradoxical or fortunate that this monument was not destroyed or at least mutilated, since the bronze frieze surrounding the pedestal depicts Queen Marie wearing a nurse uniform and portraying „the mother of the wounded”. The monument of George I. Duca (1924, sculptors Dimitrie Paciurea and Filip Marin, architect Ștefan Burcuș), found in the North Railway Station Square, on the corner of Griviței Road, was demolished in 1983 and remade after 1987 because of the works for the underground network in the area.

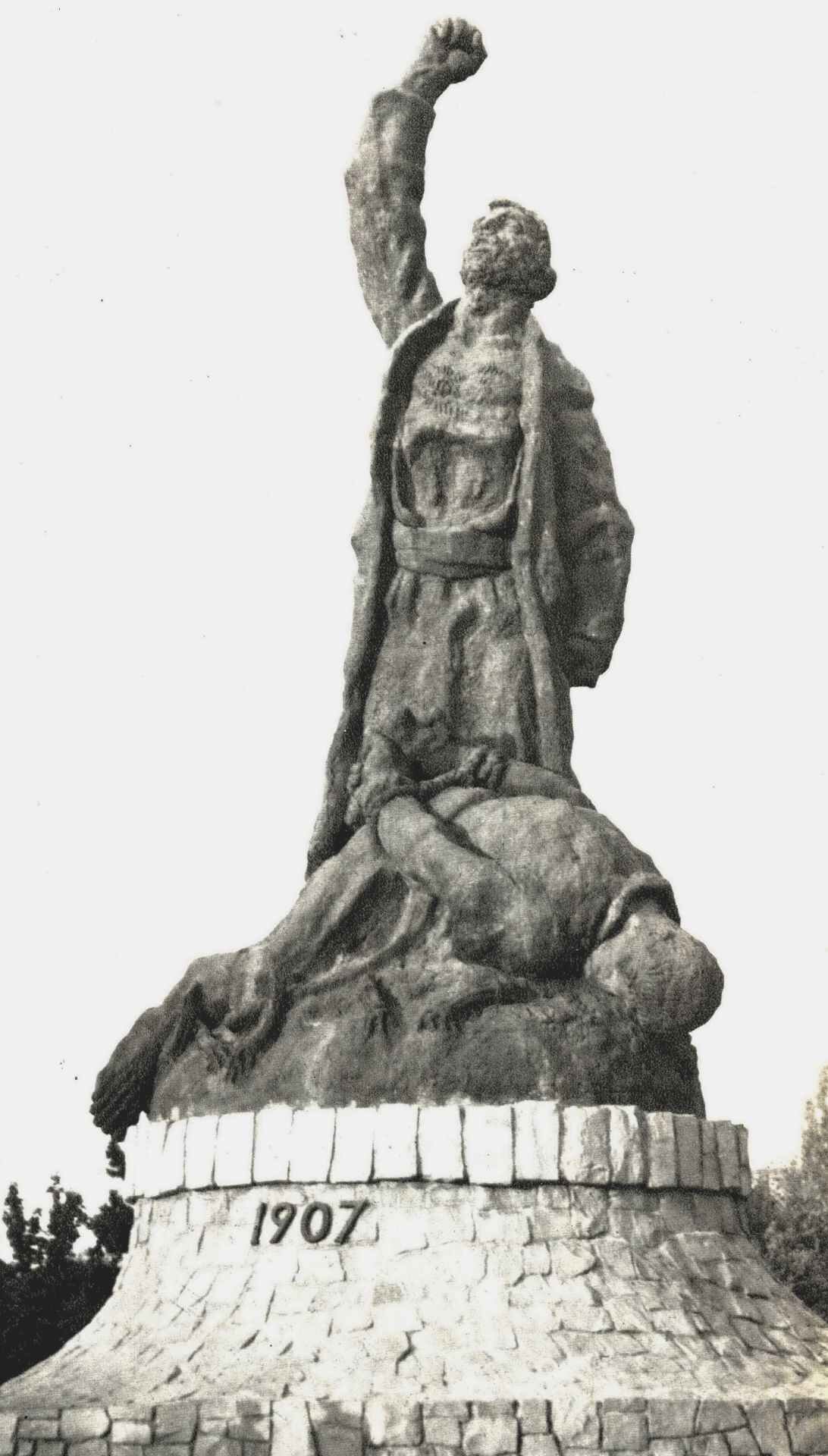

A somewhat smoother passage through the political regime change in 1989 was experienced by the social realist monument commemorating the Peasant Revolt of 1907, designed in 1957 (sculptor Naum Corcescu) and installed in Obor Park in 1972. As the City Hall District 2 was built in the area, in 2004 the statue was dismantled, thoroughly restored and appropriately relocated in the Flowers Park, Pantelimon neighbourhood, in 2007.

Yet as long as the large squares in the city (such as Revolution Square, Victory, Charles de Gaulle, Union and even University, but also others) are far from having a coherent definite expression, the location of monuments will be inherently marked by insecurity. A relevant example is Revolution Square where, over the course of two decades after 1990, five monuments of a totally different extraction have been located, despite the absence of a definite zonal urban plan: a small monument dedicated to the 1989 Revolution in front of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the statue of Ion Maniu (sculptor Mircea Spătaru), the bust of Corneliu Coposu (sculptor Mihai Buculei) near Kretzulescu Church, the Monument to the Heroes of the Romanian Revolution of 1989 (2005, sculptor Alexandru Ghilduș) and the equestrian statue of Carol I. Only two of them, the statues of Iuliu Maniu and Corneliu Coposu, are acknowledged as artistic achievements valorized accordingly through their position. Yet as a whole, Revolution Square (formerly known as the Royal Palace Square) has virtually become a repository of statues, the most controversial monument, both in terms of location and expression, being that commemorating the Heroes of the Revolution of 1989, officially named the Rebirth Memorial but commonly transformed into laughing stock.

We should also mention the case of the Century Cross, a monument conceived by Paul Neagu (1938-2004) and situated at the centre of Charles de Gaulle Square; in 2011, it was moved, on an allegedly provisional basis, a few hundred metres to the north, in Bordei area, on Aviators’/Beijing Avenue. The relocation of the monument was due to the intention of building an underground tunnel in the area, connected to a parking lot and a commercial centre, a highly controversial investment eventually discarded by the municipality, without the statue returning to its initial place; all for the best, since the monument fits better in the new site.

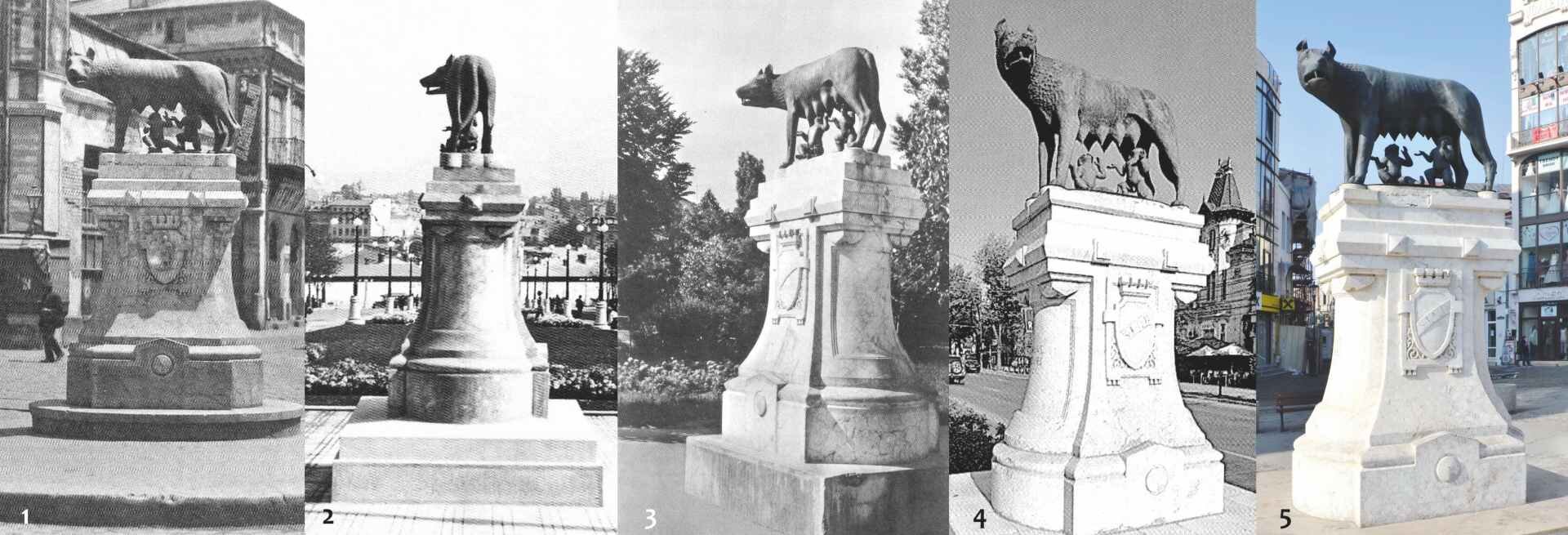

The odyssey of Bucharest monuments cannot leave out the case of Lupa Capitolina, the most „promenaded” statue in Bucharest, which virtually toured the city over the course of a century as it was moved six times to five different places, every time for circumstantial reasons devoid of any political connotations. In 1906, the small bronze statue was received as a gift from the Rome Municipality on the occasion of the Jubilee Exhibition in Carol Park, its first location. In 1908, it was installed, on a definitive basis, at the end of Lipscani Street, in a plaza formerly known as Roma Square. Given the extension of Colței Avenue (later named Brâncoveanu Avenue, 1948 Avenue in the communist period and I. C. Brătianu Avenue at present), at the beginning of the 1930s, the statue was moved to Mitropoly Hill, in front of the Patriarchy bell tower. After 1965, it was placed in a park in the middle of Dorobanți Square. While there, one of the twin babies suckled by the she-wolf was stolen on two occasions. In 1997, it was again moved, this time at the end of Lascăr Catargiu Avenue overlooking Roman Square. After less than 15 years, in 2010, it was further relocated on the spot it had been installed on about 100 years ago, at the end of Lipscani Street, relatively opposite New Saint George’s Church.

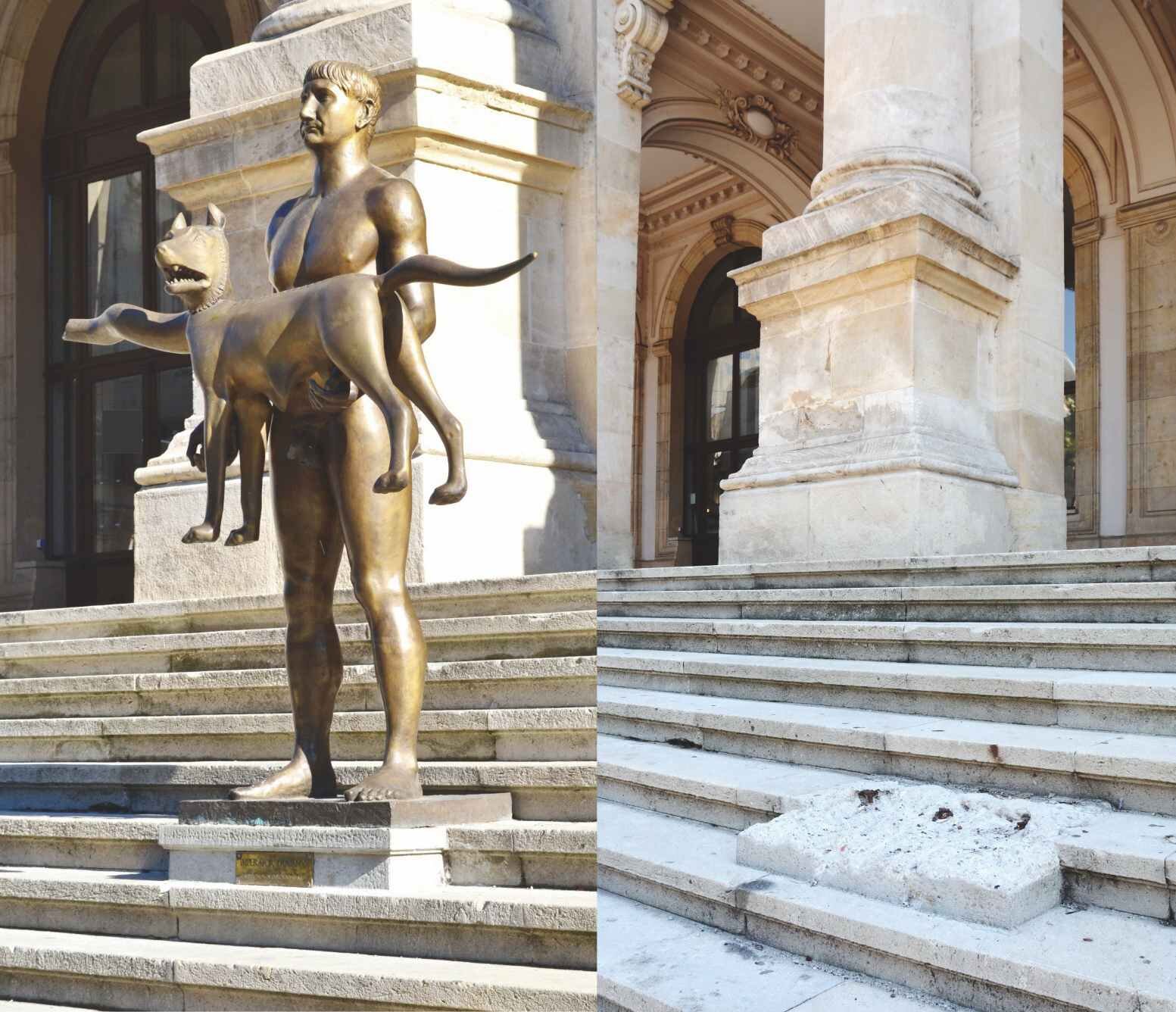

In 2012, there was much controversy about the courageous location of the statue Imperator Traianus (sculptor Vasile Gorduz) on the steps of The Romanian National Museum of History. The work stands out through its subtle symbolism, displaying a high artistic quality of modern extraction craftily making use of a classical form. It is a replica of a statue originally located in Seville in 1993, another copy being installed in 1994 in the garden of Accademia di Romania in Rome. The monument was appreciated by many but also strongly criticised and mocked by a highly vocal group of protesters active on social media, shocked by the location and the novelty of the composition alike, many of whom were too prudish to understand and accept the nude representations of the male human body.

Eventually, the statue was „vandalised”(?) in September 2017 and was disassembled on the pretext of reparation. Unexpectedly, in October 2018, the monument relocation in Floreasca Park was put up for debate in the Technical Commission on Urban Planning, on a paltry site which seriously affects its value, initiative that we hope will never materialize.

The interest taken by the communist regime in erecting public monuments in Bucharest came forward chiefly during the first decades, reflecting the wish of the new power to achieve legitimacy through works of art. It was a time when the previously mentioned monuments were built or conceived (The Soviet Soldier, I. V. Stalin, The National Heroes, V. I. Lenin, the Peasant Revolt of 1907, Petru Groza), all of them tributary to the social realist style.

In the context of the relative cultural liberalization of the 1960s, a special case was represented by the 1965 debate concerning the erection of a statue of Mihai Eminescu – the stake was giving up on socialist realism in favour of modern approaches. The obsolete scale model of the statue proposed by Constantin Baraschi, temporarily displayed in front of the National Military Circle gave rise to strong criticism in the cultural papers of the time. In the end, they preferred the statue of sculptor Gheorghe Anghel portraying Eminescu in a hieratical position and displaying a pensive and melancholic attitude; the monument was erected in front of the Romanian Atheneum. To make room for the sculpture, the statuary group The Runners (1912, sculptor Alfred de Boucher) was relocated on Victoriei Road, in the green space near the Ministry of Economy.

NOTES

1 The revised and complemented article dwells on the chapter „Agitata existență a monumentelor din București” [The Restless Existence of Bucharest Monuments] in De la Casa Scânteii la Casa Poporului, patru decenii de arhitectură în București 1945-1989 [From Free Press House to People’s House, Four Decades of Architecture in Bucharest] Simetria, 2012, p. 238-246. Bibliographical and illustration sources: Ioana Beldiman, Sculptura franceză în România (1848-1931) [French Sculpture in Romania], Simetria, Bucharest, 2005; ed. Anca Benera and Alina Șerban, București. Materie și Istorie. Monumentul public și distopiile lui [Bucharest. Matter and History. The Public Monument and Its Dystopias], Romanian Cultural Institute Press, Bucharest, 2011; Dan Berindei, Sebastian Bonifaciu, București, Ghid turistic [Bucharest, Tourist Guide] Sport-Turism, Bucharest, 1978; Valentina Bilcea and Angela Bilcea, Dicționarul monumentelor și locurilor celebre din București [Dictionary of Famous Monuments and Places in Bucharest], Meronia, Bucharest, 2009; Cezar Petre Buiumaci, Ieri și astăzi în București - Then and now in Bucharest, Bucharest City Museum Press, 2016; Șerban Caloianu and Paul Filip, Monumente bucureștene [Monuments of Bucharest], Monitorul Oficial RA Press, Bucharest, 2009; Constantin C. Giurescu, Istoria Bucureștilor [The History of Bucharest], Sport-Turism, Bucharest, 1979; Alina Ioana Șerbu, Marius Butunoiu, Meridiane, Bucharest, 1983; online resources: hhtp://ro.wilkipedia.org, accessed on 29th July 2018. Photo credits: Rodica Panaitescu, Arch. Alexandru Panaitescu, Arch.

2 Apud Ioana Beldiman, op.cit., p.146

3 After the completion of an underground car park at University Square in 2012 and as a result of the uninspired rearrangement of the lot, after being temporarily relocated to Izvor Park, the four statues are currently lost in a sea of concrete, as a consequence of an architecture competition with badly applied results; therefore, the statue of Mihai the Brave is flanked by two bus shelters (see also the case of the statue of Lascăr Catargiu).

4 In January 2014, The General Council of Bucharest adopted a resolution concerning the construction of a new monument dedicated to Ion C. Brătianu in University Square, with no real effects up to the present.

5 The name has no connection to the Legionary Movement.

6 The Arch of Triumph on the Avenue represented a monumental crowning of a series of several circumstantial attempts hastily executed on a provisional basis in different parts of Bucharest, occasioned by the celebration of various political events or military victories – in 1848 and 1878, winning the War of Independence, in 1906, on the occasion of celebrating the 40-year reign of King Carol I or in December 1918, when the sovereigns and government of Great Romania returned to the capital after having tragically taken refuge in Iassy. In the 1980s, as an expression of Nicolae Ceaușescu’s cult of personality, a great arch was erected, a kind of „triumphant” gate at the entrance to EREN - The Exhibition of National Economic Achievements (currently Romexpo) in Free Press Square (formerly Scânteii Square), awkwardly made from a metallic and wooden structure covered in burlap fabric painted in ochre and decorated with a few pseudo-folk elements. This inadequate composition entitled „The Arch” was short-lived as it was destroyed one night by a fire, an allegedly anti-communist sabotage.

7 In the fifth and sixth decades of the last century, Nestor Culluri taught notions of sculpture and modelling at „Ion Mincu” Institute of Architecture.

8 Eugeniu Carada (1832-1910), a close friend of I. C. Brătianu and one of the most influential leaders of the Liberal Party. His entire activity is linked to the foundation and development of the National Bank as he is considered one of its main founders. He initiated the construction of the Palace of the National Bank of Romania and directly supervised the execution of the works.

9 Deemed one of the most efficient mayors of Bucharest, Emanoil Protopopescu Pache (1875-1893), launched, during a very short term (1888-1891), numerous important urban planning and public works such as: the construction of the two main central avenues on the east-west axis (Carol-Regina Elisabeta) and the north-south axis (Colțea-Brătianu), as well as street alignment plans, the introduction of electric lighting on various avenues, the construction of the first electric tram line, the upgrading of the water supply network, the construction of numerous schools etc.

10 See „Gânduri despre ansamblul statuar al Grotei Giganților din Parcul Carol”, [Reflections on the Giants’ Grotto Statuary Ensemble in Carol Park] by Ioana Beldiman, in Confluențe arhitecturale, [Architectural Confluences], Ozalid, Bucharest, 2018.

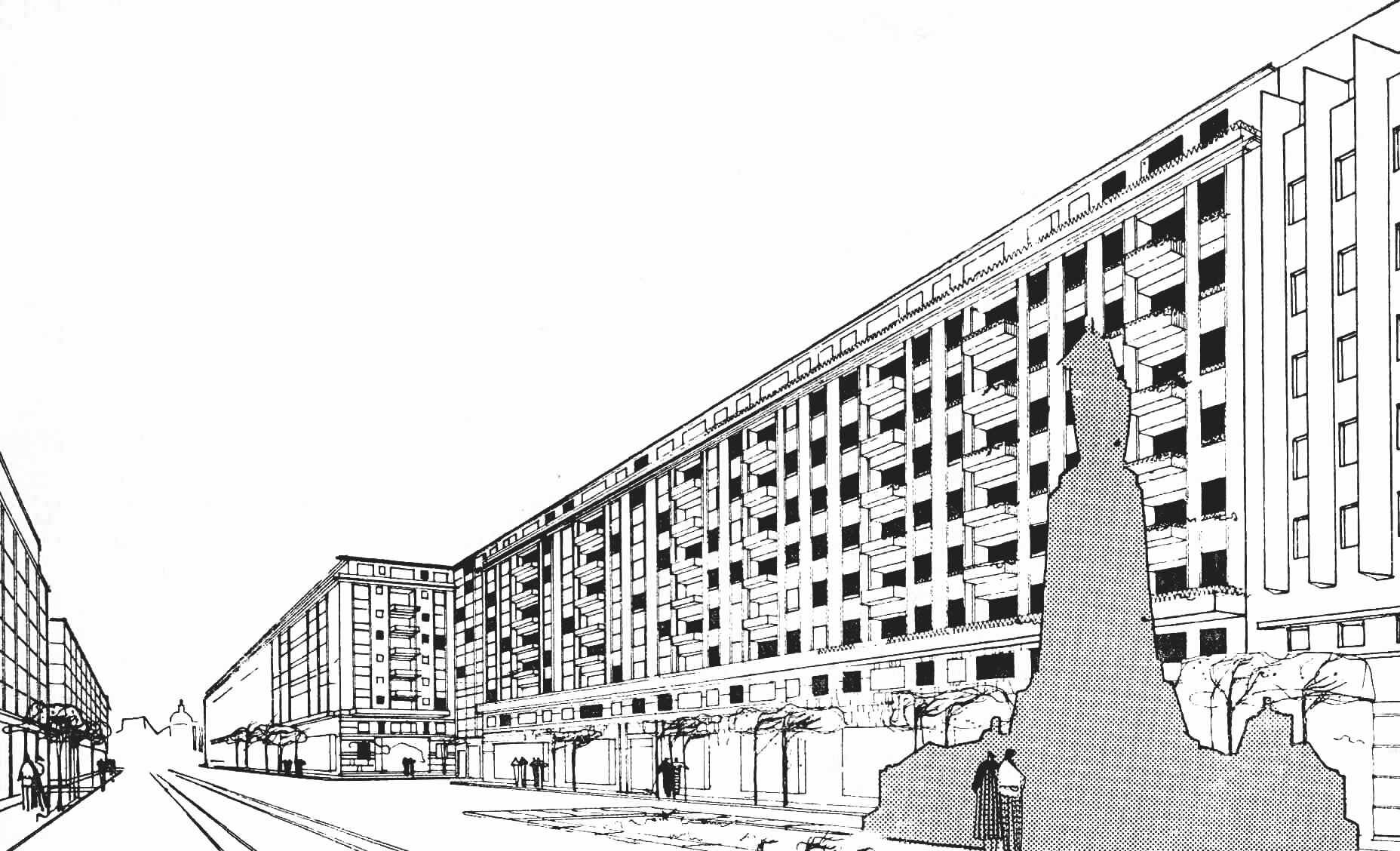

11 According to a perspective published in Arhitectura no. 10-11/1958.

12 In the 1950s until the beginning of 1962, Herăstrău Park was known as I. V. Stalin Cultural and Recreational Park after it had been previously called King Carol II National Park, from the 1930s until September 1940, as it had been created on the King’s initiative. As of January 2018, it was renamed King Michael I Park.

13 According to the monarchic propaganda of the 1930s, on 6th June 1930, the plane bringing Prince Carol back from the exile was forced to land for refuelling on a field near Vadu Crișului village in Bihor. There, a young woman whose family name was Mudura or Modura offered the future King Carol II (1930-1940) a jug of cold water to quench his thirst. The gesture, seen as a good omen for the new reign, was to be highly promoted, the episode or the young woman’s figure being subject to various artistic representations, including on a gold coin issued on 8th June 1940.

14 See the testimony of the former architect-in-chief of Bucharest, Alexandru Budișteanu, in a dialogue with Flori Bălănescu - Între istorie și judecata posterității [Between History and the Judgement of Posterity], The National Institute for the Study of Totalitarianism Press, Bucharest, 2010, p. 179.

15 As a documentarily unconfirmed anecdote, there was a rumour running in the artistic world saying that the statue of I. L. Caragiale was actually the bronze scale model for the monument of V. I. Lenin proposed by Constantin Baraschi at the end of the fifties. As he lost the commission in favour of Boris Caragea, sculptor Baraschi would have replaced Lenin’s head with that of the famous playwright from a desire to capitalize his work in some way.

16 After 2007, it was suggested that a monument (sculptor Ioan Bolborea) should be erected to commemorate the Great Union in Alba Iulia Square. The highly controversial and extremely expensive work determined the municipality to give up the project whose execution was to be completed in 2018.