ateliercetrei

| Monica Lotreanu: Cum ați înființat biroul de arhitectură OVO Grąbczewscy Architekci? Cum vă organizați activitatea? Angajați și alți specialiști, alți profesioniști în afara arhitecților, de exemplu pentru ingineria structurilor, pentru design interior sau amenajare peisagistică sau orice altă consultanță tehnică? Spuneți-ne povestea biroului dvs. de arhitectură. Oskar Grąbczewski: Am înființat biroul de arhitectură împreună cu soția mea, Barbara, după ce lucraserăm împreună din anul 1995, în firma de proiectare a unui reputat arhitect polonez, Ryszard Jurkowski, unde, într-o oarecare măsură, ne-am câștigat experiența ca arhitecți profesioniști. În 2002, am decis că a venit vremea să ne deschidem propriul nostru birou. La început am câștigat concursul pentru Pavilionul și Muzeul Paleontologic din Krasiejów și, la vremea aceea, tactica noastră a fost să participăm la cât mai multe concursuri și să încercăm să obținem proiecte publice. Și am avut succes. Am câștigat câteva concursuri, am început să realizăm proiecte și să construim. Practic, în felul acesta ne conducem biroul. Cele mai multe dintre proiectele noastre provin din sectorul public, dar realizăm proiecte și pentru investitori privați, inclusiv case și clădiri comerciale mai mari; în continuare, domeniul public constituie principalul nostru interes. Suntem un birou de arhitectură structurală, de aceea nu angajăm alți ingineri. Este un fapt des întâlnit în Polonia ca firmele de arhitectură să se ocupe de partea de arhitectură, iar pentru proiecte să existe contractori generali. Și apoi avem subcontractanți precum ingineri mecanici, ingineri de statică și electrice. Uneori realizăm un fel de consorțiu pentru proiecte mai mari, de exemplu, pentru concursul Liget Budapest unde, în prima fază, am lucrat propunerea în birou, apoi ne-am clasat printre cei șase finaliști și am creat un consorțiu cu Arup Polonia să finalizăm proiectul din faza a doua a concursului. Prin urmare, am fost foarte mulțumiți să colaborăm cu ei și lucrăm împreună din când în când. În orice caz, revenind la biroul nostru de arhitectură, suntem o mică afacere de familie, să zicem. Avem maximum 10 angajați. Poate, pentru noi, aceasta este cea mai bună modalitate de a păstra contactul cu activitatea de proiectare și de a avea cu noi oameni care ne ajută, dar și de a ne simți totuși autorii structurii, autorii clădirii. M.L.: La câte concursuri de arhitectură participați anual, să spunem? Sunt internaționale sau naționale? O.G.: Cred ca ar putea fi aproximativ 6 până la 10 concursuri anual, în principal pe plan național, dar participăm și la concursuri internaționale și, bineînțeles, acestea sunt mai dificile și mai complexe, însă ne place din când în când să facem lucruri mai complicate și la o scară mai mare pentru a încerca să nu ne concentrăm pe lucruri mici. În activitatea noastră, așa cum am spus, există o gamă largă de proiecte, de la case particulare la săli de sport sau piscine. De cele mai multe ori ne place această schimbare de amploare și nu dorim să ne specializăm în ceva anume. Prin urmare, dacă întâlnim ceva interesant, cum a fost acest concurs din Parcul Liget sau alte concursuri pentru muzee sau clădiri publice mai mari, suntem foarte dornici să participăm. M.L.: Să ne întoarcem acum la unul dintre proiectele importante ale biroului dvs. de arhitectură pe care l-ați prezentat în conferința RIFF: Muzeul Focului. Cred că ar trebui să explicați tema proiectului și, de asemenea, de ce această denumire și cum vi s-a încredințat proiectul? O.G.: Da, este o poveste interesantă, deoarece comanda inițială a fost destul de diferită de ceea ce s-a întâmplat ulterior în proiect. Am fost desemnați să proiectăm un pavilion printre altele promoțional pentru Żory, un oraș mic, de aproximativ 70.000 de locuitori, situat în Silezia, lângă Katowice. Am mai colaborat cu municipalitatea din Żory când am realizat proiectul pentru muzeul ecologic. Au fost foarte mulțumiți de proiectul realizat de noi, pentru care am și obținut premiul pentru tineri arhitecți europeni sub 40 de ani. Nu au reușit să îl construiască din motive financiare. Dar, fiindcă au fost mulțumiți de lucrarea noastră, au decis să ne încredințeze proiectarea acestui mic pavilion, situat chiar la șosea, la intrarea în oraș. Ideea lor era ca pavilionul să promoveze orașul și să trezească interesul oamenilor care treceau pe acolo. Trebuia să fie și un semnal, o emblemă a orașului... Și ne doream să fie clar un pavilion modern, ca o seră în stil Philip Johnson... ceva în acest spirit. De fapt, cred că la început am făcut o mare greșeală, deoarece ne-am gândit să fie o cutie de sticlă foarte simplă, o soluție foarte clară. Cu această idee, ne-am blocat total în proiect. Nu reușeam să avansăm, deoarece terenul era foarte complicat. Existau multe conducte subterane și aveam la dispoziție două sau trei săptămâni pentru a prezenta proiectul. Trebuia să luăm o pauză și am luat o pauză. Am plecat într-o excursie în Italia și, în timpul vizitelor, am luat cu mine unele schițe; într-o zi, stând de vorbă cu soția mea, am realizat că forma terenului și forma clădirii care putea fi amplasată pe acesta îmi aminteau de foc. A fost o idee foarte ciudată, complet abstractă, dar după aceea am realizat că trebuie să luăm proiectul de la început. Și ne-am întrebat ce este reprezentativ pentru acest oraș, cum ar trebui să arate clădirea. Deodată, am descoperit, sau fusese clar, doar că nu observaserăm noi, că orașul Żory are o legătură foarte strânsă cu focul, deoarece numele orașului înseamnă în poloneza veche „foc” sau „flacără”. Este foarte ciudat cum ne-a scăpat acest aspect. Și apoi, nu numai numele orașului are legătură cu focul, dar și istoria orașului, deoarece Żory a ars de mai multe ori în incendii foarte puternice. În secolul al XVIII-lea, a fost aproape complet distrus de foc. Și, mai mult (era în luna mai), acest fapt a dat naștere unei tradiții a ceremoniei focului deoarece, a doua zi după acest incendiu uriaș, toți locuitorii au participat la o procesiune religioasă... pentru a-l invoca pe Dumnezeu. Această tradiție s-a perpetuat până în zilele noastre: aproximativ10.000 de oameni se strâng seara, participă la o slujbă la biserică și apoi, cu torțe aprinse, traversează orașul, iar asta marchează debutul unui festival. Când am descoperit această istorie și am înțeles ce ar trebui să facem, ne-am propus ca pavilionul să arate ca un foc. Și foarte repede, cam în două zile, am realizat proiectul care s-a potrivit perfect pe acest teren complicat. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 1 / 2016 al Revistei Arhitectura |

| Monica Lotreanu: How did you start your studio, OVO Grąbczewscy Architekci? How do you organize your activity? Do you employ other professionals than architects, for instance for structuring engineering, for design or landscape or for any other technical advice? Tell us the story of your studio. Oskar Grąbczewski: We started our studio together with my wife, Barbara, after working since 1995 in the studio of a renowned Polish architect, Ryszard Jurkowski, and somehow we gathered our experience as professional architects there. In 2002, we decided that it’s time to start our own studio. We began by winning the competition for the Palaeontological Pavilion and Museum in Krasiejów and at the time our tactic was to make a lot of competitions and to try to get public commissions. And we have been successful – we won some competitions and we started to make projects and to build things. And this is how we are running our studio, basically. Most of our commissions come from the public sector, but we are also making some projects for private investors including houses and bigger commercial buildings; still, this public domain is our main interest. We are an architecture studio. So, we don’t employ any other engineers. It is very common in Poland for architectural studios to deal with architecture assigned by general contractors for projects. Then we’ve got subcontractors like mechanical engineers, statics and electrical engineers. Sometimes we make a kind of consortia for bigger projects. For example, for the Liget Budapest competition in the first stage, we did the project in the studio, but we made it to the final six, so we made a consortium with Arup Poland to complete the project for the second phase of the competition. We were very glad to work with them, and we have continued working with them from time to time. Well, anyway, we are a small, let’s say, family business. We are employing up to ten people, maximum. Perhaps this is the best way for us to keep the contact with the design and to have people who are helping us, but still feel as we are the authors of the structure, the authors of the building. M.L.: How many competitions do you enter annually, let’s say? International or national? O.G.: I think it could be about 6 to 10 competitions per year, mostly national, but we are also making international competitions and, of course, they are harder and more complex, and we like from time to time to make something that’s more complicated and on a bigger scale in order to try not to concentrate on small things; as I told you, our work has quite a wide range, from single family houses to sport halls or swimming pools. So basically, we like this change of scales and we don’t want to specialize in anything. Therefore, if we find something interesting, like this Liget Park competition or other competitions for museums or bigger public buildings, we are very willing to participate. M.L.: Let’s return now to one of the important projects that your studio delivered and you presented in the RIFF conference: The Museum of Fire. Perhaps you could explain the project brief and also its title and how you were commissioned for the project. O.G.: Yes. This is a very funny story, because our assignment was quite different from what happened till the end. We were commissioned to design a promotional pavilion for Żory, a small city of like 70,000 people, in Silesia, near Katowice. We worked together before with the mayoralty Żory, for the design of the ecological museum. They were very glad about our project, for which, among others, we got an award for young European architects under forty. They couldn’t build it because of financial restraints, but they liked our work and decided to commission us another project. This was a small pavilion, located on the very gate of the city, meant to promote and raise interest for the city to the people passing by. It also had to be a signal, an icon of the city... And we wanted it to be a clear modernist pavilion, like a glasshouse from Philip Johnson... something like this. I think, in fact, at the very beginning, we made a big mistake because we figured out that it would be a very simple glass box, a very clear solution. But we got totally stuck in this project. We were not able to go any further because the plot was very complicated. It was disturbed by many underground pipes and in fact we were having two or three weeks left to present the project. We had to make a break, and we made a break. We took a trip to Italy and during the visits I took some sketches with me; one day, as I was sitting there talking to my wife I realized that the shape of the plot and the shape of the building applicable to place in this plot reminded me of fire. It was a very strange idea, totally abstract, but after that we realised we should start the design from the very beginning. We asked ourselves what is specific for this city, what this building should look like. Suddenly, we discovered – perhaps it was quite obvious but we didn’t see it – that the city of Żory is very strongly connected to fire, because the name of the city translates with “fire” or “flame” in old Polish. It is very strange how we had missed it. And then, not only the name of the city relates to fire, but also the history, because Żory was burnt several times by huge fires. In 18th century, it was almost completely burnt down (it was in May), and there has started the tradition of a fire ceremony: the next day after this huge fire, all the people went in a procession to invoke God… And this tradition lasts till today: around 10,000 people are gathering in the evening for a mass in the church, and then they are walking through the city, with fire, torches, and that is the beginning of a festival. When we came up with this history and we understood what we should do, we said we should make this pavilion look like fire. And very fast, like in two days, we made the design that perfectly fit in this complicated plot. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine |

Muzeul Focului, str. Katowicka 3, Żory, Polonia, 2015 | Museum of Fire, Katowicka Street 3, Żory, Poland, 2015 - © Tomasz Zakrzewski/ archifolio

Muzeul Focului, str. Katowicka 3, Żory, Polonia, 2015 | Museum of Fire, Katowicka Street 3, Żory, Poland, 2015 - © Tomasz Zakrzewski/ archifolio

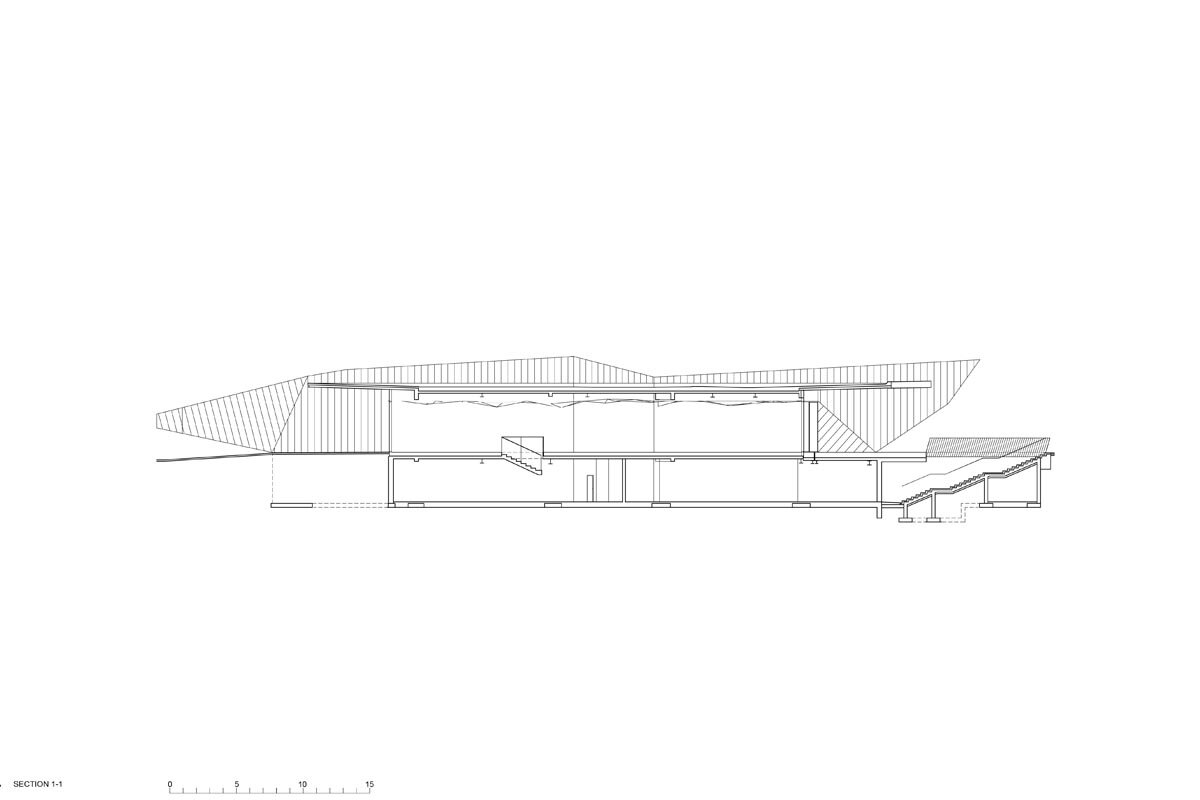

Muzeul Focului, secțiune | Museum of Fire, cross section plan

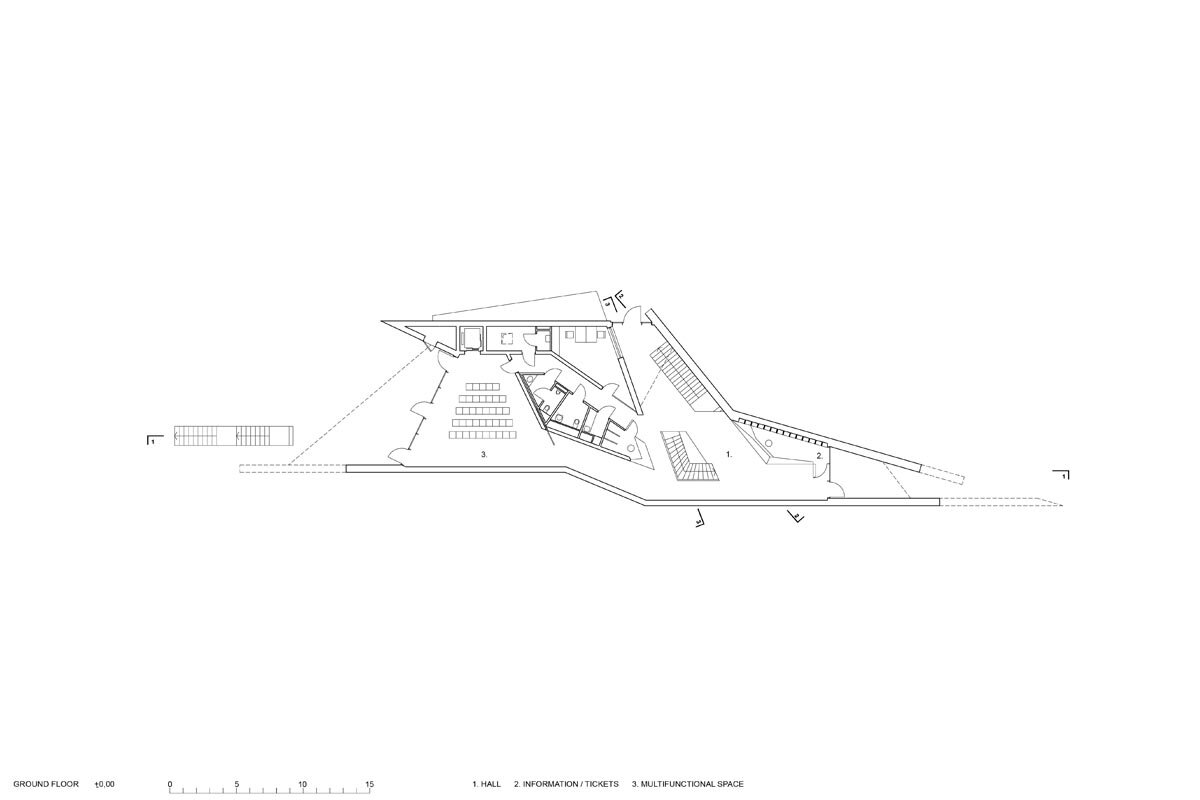

Muzeul Focului, plan de parter | Museum of Fire, ground floor plan