Thermal renovation of Bucharest (pamphlet)

Motto:

"They [rhinos] are beautiful. Oh, how I wish I could be like them. [Now it's too late! Well, yes, I'm a monster. A monster! God, I'll never be a rhinoceros, never, never! I can't change anymore." Eugène Ionesco, Rhinoceros

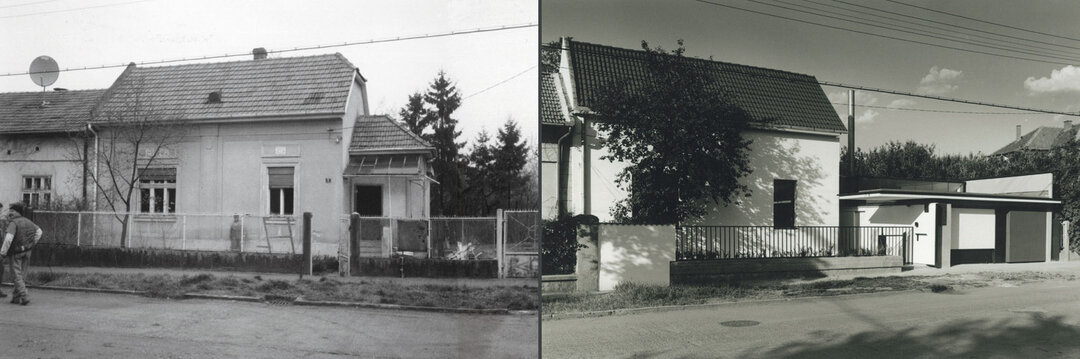

This morning, I almost took a wrong turn. I suddenly felt I was in another city. What's more, I thought I was in a nightmare where the gingerbread had turned into blocks. Although I had seen them many times, I no longer recognized the buildings in front of me. They were painted from top to bottom, like ice cream with synthetic dyes.

But I recognized the sidewalks by the way they were squat with parked cars, and I calmed down. I was in Bucharest. It's a great thing to find yourself in your native places. There is the idealized land of paradise lost, whether between houses or lost on the coast of Boacii. There are the dear people who made you human and who believe as you do.

I recounted my little thrill to a neighbor. "Never mind," he replied, "there are bigger problems." Reflecting on such a serious answer, I agreed that there are worse problems and that I would not bother mankind with my fears.

Thinking more seriously, however, about the garish coloring of the blocks as a result of thermal rehabilitation, about the closing of balconies turned into unhealthy airtight bags on the front of buildings, at risk of collapse, I met a friend and tried to adjust my shot, this time in a more joking tone. "Here it is," I told him, "the thermal rehabilitation has revived one of the oldest traditions in Bucharest: the house with a window! And at Manuc's Inn, years ago, a glazed window was installed upstairs and had to be dismantled during the restoration!" To my surprise, my "humor" had no effect. I understood that he had also had his block renovated, with money from the ministry and the town hall, and that he couldn't comment on it. In that case, I couldn't say anything to him either.

In a weak voice, I asked a friend, who is not an architect, what he thought. "Terrible. A fairground. Horrible colors." Here is a man who understands - I said to myself - that these political colors were imposed by the specifications. He continues: "is this what architects are designing in Romania now? What is the Order of Architects doing? I replied that the Order of Architects makes public statements explaining that apartments are no longer ventilated, that they have become unhealthy greenhouses, that it has sent to the ministry and to town halls the set of measures that the French apply in these cases. He replied that it was not enough.

I also explained to him that at least the balconies should not be closed, because they were originally designed that way for enough reasons. First of all, the urban density did not allow for a closed room, which is why balconies were made. And, more importantly, the structure of the block was not designed for the extra weight added by the glazing and the payload of the furniture, which is greater for an enclosed space than for a balcony. It is incredible what has been happening over the last few years: instead of strengthening the blocks, we are adding weight. What's more, the polystyrene installed on facades often doesn't follow the doweling instructions, so there is a risk of detachment. Thermal rehabilitation is the biggest architectural operation in Romania to put buildings at seismic risk with public money!

"Yes, but we'll see until the earthquake," my friend replied.

It's true, I said to myself, that's the general thinking. Judging by how many blocks are being thermally rehabilitated, it means that the majority of the insufficiently informed inhabitants are in favor. That's over 1,600 blocks painted in 3 years. And 600 million euros invested. Costs 18,000 euros per apartment. A historic chance for Bucharest to return to the architect-designed architecture practiced in our inter-war capital was missed.

The next night I actually had a dream. I was sitting at home, waiting for a law that would also thermally rehabilitate my house. I didn't know what color it would be, I only knew that from the inside I wouldn't be able to see it and, walking down the street, I would pretend it wasn't my house.

Thank God, but now I'm awake and my reason is not asleep. I know it is my house, and I don't want anyone to renovate it in a chaotic fashion, to paint it in whatever garish colors they want, and to seal it up in glass that will shatter in an earthquake. And it's my city, and I don't want them to turn it into the colors they want, depending on how they change its color. And it's my country, which I would like, finally, to rehabilitate, but not just thermally.