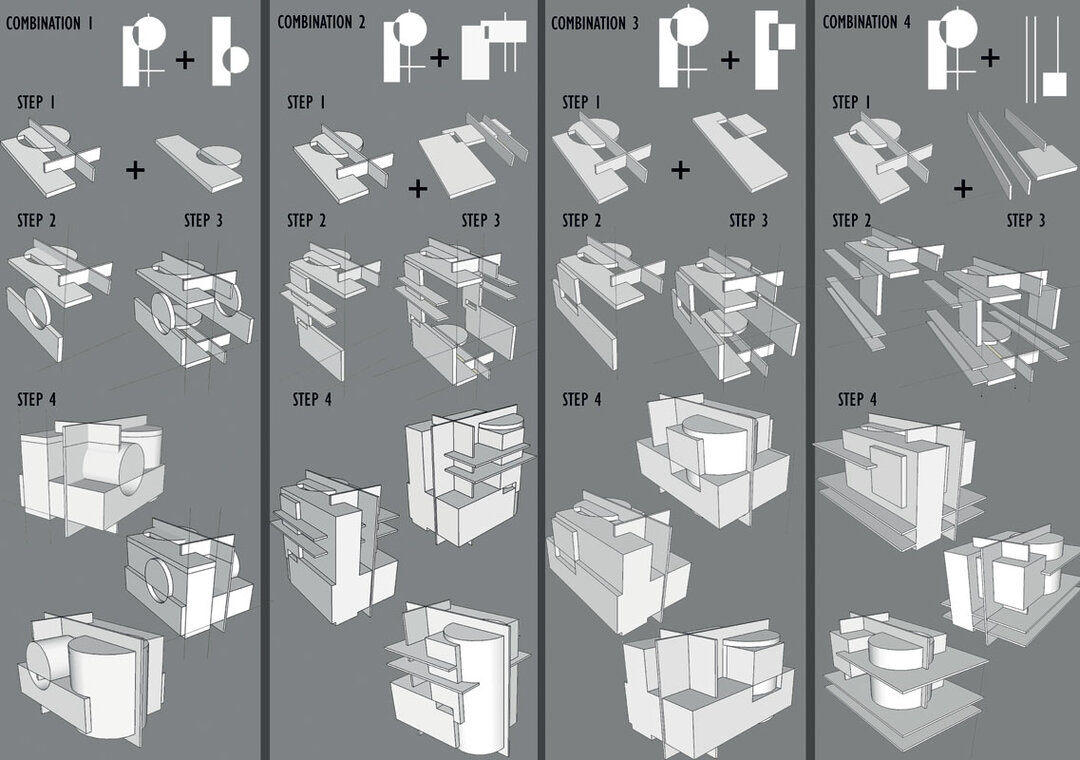

Trans-fund, trans-function and trans-form

Trans-substance, trans-function and trans-form

| ... Then the frog turned into a beautiful princess. Then the lion turned into a stone rock. Dr. Jekill turned into Mr. Hyde. The desert turned into a marvelous city with a wealth of lights, and the shabby hamlet into a majestic castle with a hundred towers. |

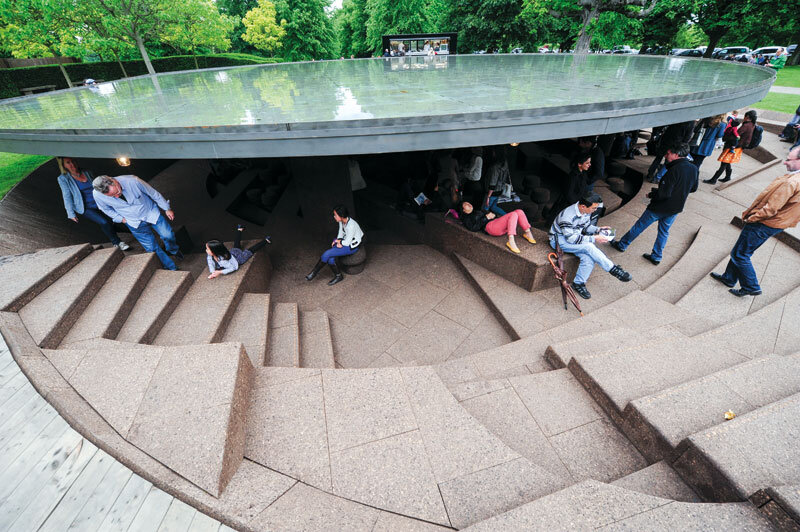

| The structure of the evolving imaginary Spontaneous, radical, unitary and univocal transformations are not only appropriate, they are marvelous in the world of innocent spirits and in imaginary worlds. But a kind of innocence also urges such solutions in the real world. So I believe that the yearning for miraculous transformations is genuinely contained in the very structure of the human imagination. The human spirit is then cultivated, nuanced and more or less detached from this naïve beginning. The same happens to the man who has become an architect. Or not. This spirit that we like to call imaginary is of two kinds. One is slobod and astral and is called imagination. Associated with a Maoist morality, imagination gives charm and value to fairy tales. In the arts, imagination is the fuel of creativity, and in architecture, when wielded by its magicians, it turns a space into a state and a form into a trans-form. With trans from trans-cendent. Or trance. The imaginary other is a subtle fabric that interweaves itself between us and reality, a fabric that seems transparent, but in fact creates images that discreetly distort reality - sadistically complex, no doubt. Therefore, even if fed by reality, images of reality are structured by our imaginary and are our own. These are what we question when we propose to change places through our architecture. We also call architecture spatial planning. And we love to design and modify - whether we need to or not. So much so that there would be enough among us willing to landscape forests and mountains, if you let them (read pay). With steps, with benches, and maybe even artesian wells. Just as others landscape their waterfront until the sea can only be seen on Google Earth. The further south, the steeper. Got a path? Pave it! Or pave it! But make it a wide alley, you know a job. You got a couple of God-given acacia trees? Shave 'em! Maybe put in a crate of Hornbach thuja. Got a slope? Put lots of steps on it right away! Concrete, you know. Got the slightest bit of motivation at the top? Burn a road up there! Got a pond? Either drain it, concrete it, square it, make it a pond, make it a pool, make it a "composition" - the idea is to make it not what it was, if it fit your hand. You've got the power in your pen, if you've got one in your money. Motivations can be found - and some of the most convincing to the fairy-tale audience; they are of the type: does your tooth hurt? Take it out and get rid of the infection; with treatments, the road is long and complicated. And this demiurgic power to change geography, history, society with a few grand gestures... just lines on paper - what a sweet temptation that is! I'm not talking about the countries of the North, for example, where the collective imaginary is genetically different, nor about worlds in which it is educated in a different spirit. Over there, the castle is preferred to the village, which they transform just enough to make it no longer impoverished. And if need be, they pave the pathway with stones. They don't want "evolution" and peace. And they only have examples in Dubai. More recently, in marvelous Baku. |

| Read the full text in issue 3/2012 of Arhitectura magazine. |

| ...Then the frog turned into a beautiful princess. The young man turned into a block of stone. Dr. Jekyll turned into Mr. Hyde. The desert turned into a wonderful city of countless lights, and the hovel turned into a magnificent castle with a hundred towers. |

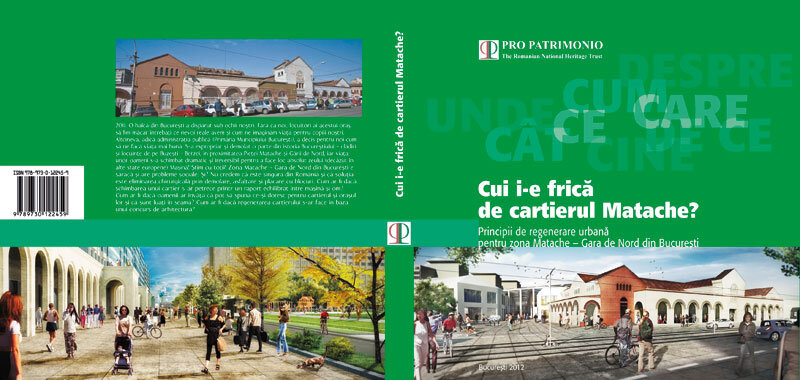

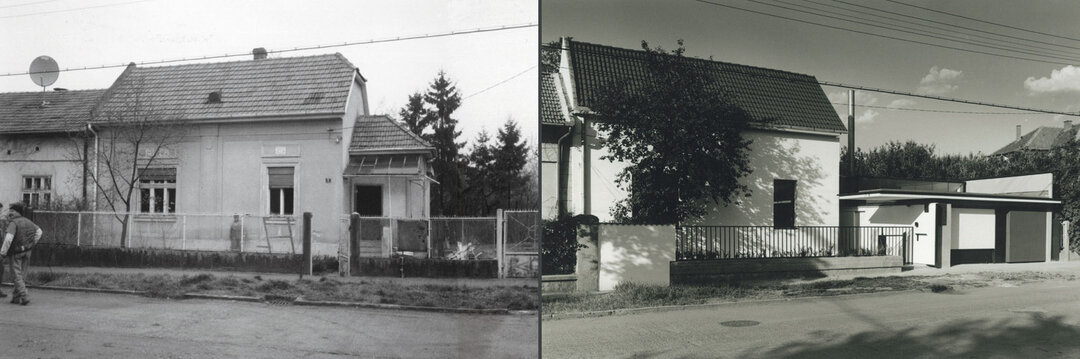

| The evolving structure of the imaginary Spontaneous, radical, unitary and unequivocal transfor-mations are not just appropriate but miraculous in the world of innocent spirits and imaginary worlds. But it is also a kind of innocence that urges such solutions in the real world. This is why I think that the striving toward miraculous transformations is genuinely contained in the very structure of the human imagination. The human spirit then cultivates itself, grows more subtle and, to a greater or lesser extent, breaks away from this ingenuous urge. The same thing happens to people who have become architects. Or else it doesn't happen. The spirit we like to call the imaginary is of two kinds. Combined with a Manichean morality, the imagination lends charm and value to fairy tales. In art, the imagination is the combustion of creativity, and in architecture, when handled by a magician, it turns space into a mood and forms into trans-forms. Trans as in transcendent. Or trance. The other imaginary is a subtle weave that stands between reality and us, a weave that looks transparent, but which in fact creates images that subtly distort reality - a reality that is sadistically complicated, of that there can be no doubt. Consequently, although nourished by reality, images of reality are structured by our imagination and come from us. We interrogate them when we set out to alter places using our architecture. We also call architecture the development of space. We love it so much that, among us, there are plenty of architects that would be prepared to develop even the forests and mountains, if you let them (or paid them to), with steps, benches, and maybe even fountains. The way others develop the seashore, to the point that the only way you can see the sea is on Google Earth. And the further south the better. Got a footpath? Tarmac it! Or pave it! Make it a wide lane, if you want to do a good job of it. Got a few locust trees? Cut them down! You can always put a potted white cedar from Hornbach in their place. Got a slope! Make a flight of steps there this instant! Concrete ones, obviously. Got a pond? Either drain it, or fill it with concrete, or make it square, or turn it into a swimming pool, or make it part of some "composition" - the point is not to leave it the way it was when you first got your hands on it. The power is all in your pen, if you've got the financial backing. You'll find reasons convincing enough for the fairy-tale-loving public, reasons that go like this: got a toothache? Get rid of the infection by having your tooth pulled out. Treatment is too lengthy and complicated. And this demiurgic power to change at a stroke geography, history and society, just by tracing lines on paper, is such a sweet temptation! I'm not talking about the Nordic countries, for example, where the collective imagination is genetic, or about worlds where it is educated in a different spirit. Over there, a hut that you can transform so that it isn't as impoverished is preferable to a castle. And if there is really a need, then flagstones will serve for a path. They don't want to "evolve" and that's that. Even if Dubai and, more recently, wonderful Baku set them an example. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |