Interview with the architect Pablo Katz: "The future history of our cities will depend on the choices of the society we form"

Interview with the architect Pablo Katz:"The future history of our cities will depend on the societal choiceswe make"

|

"A small house, a small garden can become the object of the dreams of someone who has nothing. But is it to flatter the irrational desires of ignorance?" Jean-Baptiste-André Gaudin, Solutions sociales, 18711 |

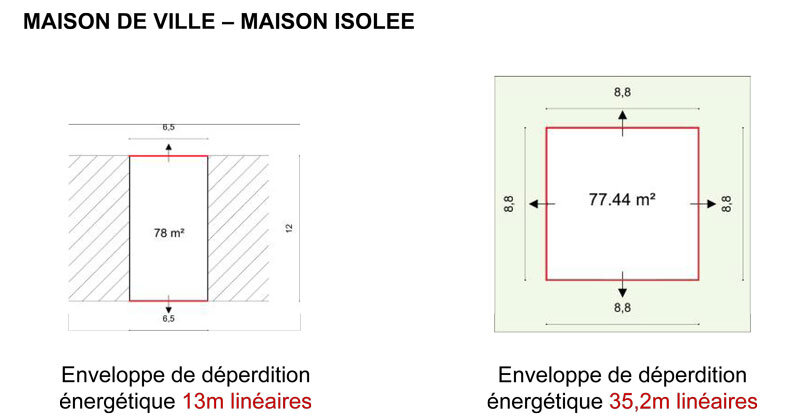

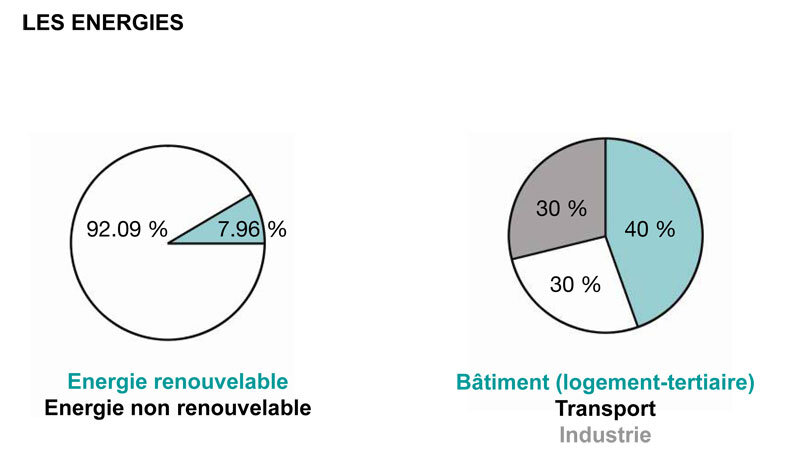

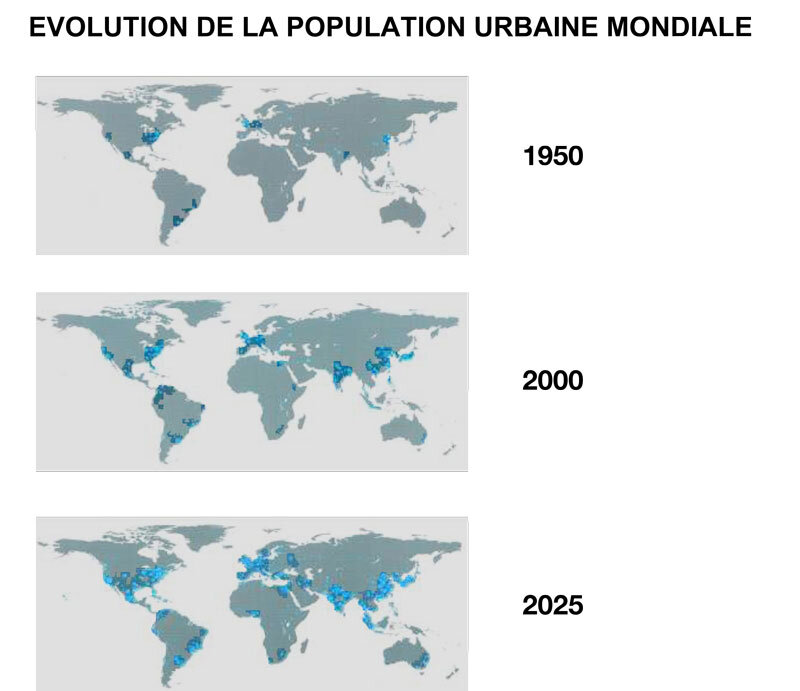

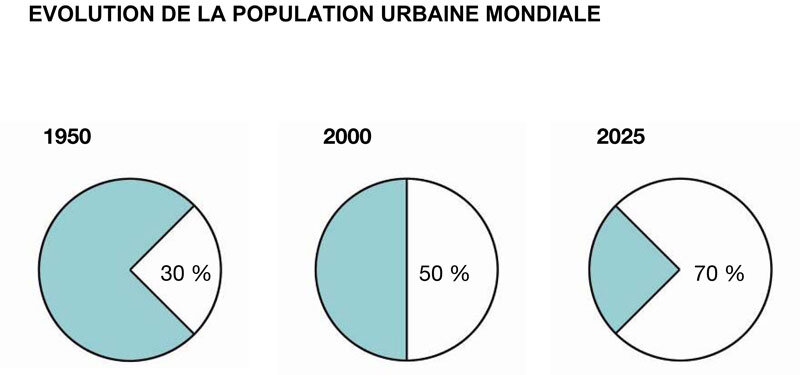

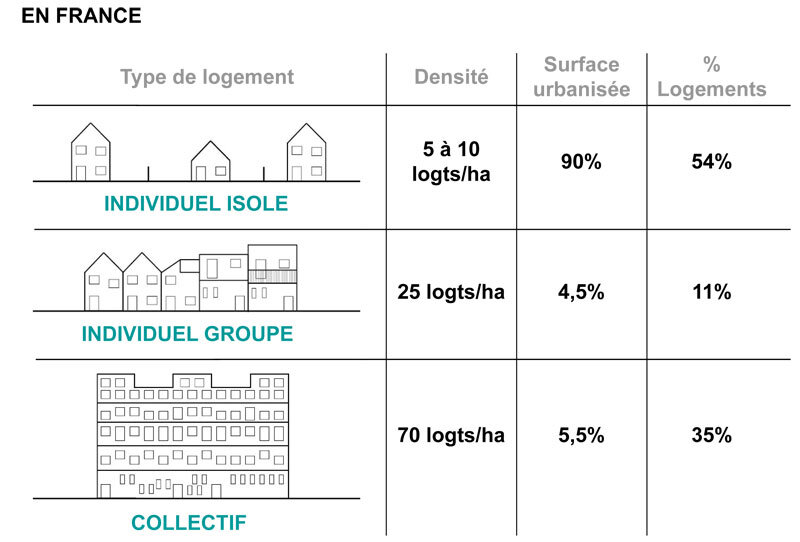

| Alina Nechifor: Your conference in Bucharest, during the Open Workshops of Architecture, analyzed urban dissolution - more precisely, its title was: "A small house, a small garden, urban dissolution" - an ironic title, as you have rightly pointed out. Could you develop this concept in a few sentences? Is this urban dislocation the result of an excess of individualism, of the fact that each of us dreams and imagines ourselves "in a small house", isolated, totally independent? What would then be the answer of your architectural practice? Pablo Katz: In 1950, there were 2 urban agglomerations of more than 10 million people in the world. 30% of the world's population was urban at that time. Today, there are 30 agglomerations of more than 10 million inhabitants and about 500 cities of more than 1 million inhabitants, while half of the world's population now lives in cities. Three quarters of the world's population will be urban by 2025. This urbanization has generally taken place in peri-urban areas, in the form of low-density individual dwellings. As a result of this urban sprawl, total arable land is shrinking every year, according to the UN, by 300,000 square kilometers, the equivalent of the size of Italy. In France, despite being a developed and dense country with an important urban history, almost 65% of the year-round housing stock is individual. The peri-urban fabric that unfolds in this form demonstrates the disengagement of politics, a capitulation of architecture, the absence of a vision of spatial planning and the inability of architects to express themselves publicly and make themselves heard. All this is symptomatic of a highly individualistic society in which each inhabitant aspires to own his or her own little house and garden. At the same time, this form of urban sprawl is extremely costly for the collectivity: it consumes natural and agricultural land, but it is also costly in terms of roads and infrastructure, precisely because of its low density. However, despite the high costs involved, these proliferating urban fabrics are completely incapable of giving rise to a city, an urbanity. The city means public space, and public space is the great absentee of these forms of residential fabric! A.N.: At the opposite pole of the monofunctional territory, of the pavilion model, we find the dormitory-cities, which are designed for habitation and which encourage the spread of revolt. You are advocating the idea that it is precisely these peripheries of individual houses, stretching out to infinity, that reproduce (by a mirror image) the shortcomings and problems that we find in dormitory towns, that they behave in some way like a dormitory town. Then we ask ourselves the question: will we be able to escape violence and isolation? How do you see all this, what do we change to live better? P.K.: Certainly, the suburbs, which lack infrastructure, services, jobs and leisure spaces, behave like dormitory towns, in the same way as a number of large housing estates. However, while it is impossible to foresee public transport, infrastructure, services, jobs and leisure in a low-density fabric, the density of the large developments will allow it. The mix of functional and social needs to be reintroduced in large residential developments and their relationship with the landscape needs to be rethought. If these large estates are a problem today, demolishing them and replacing them with small detached houses, sending their inhabitants further away each time, is not only not a solution, but also exacerbates exclusion. It is only by means of ambitious public policies on spatial planning and urban strategy that we will be able to avoid violence and isolation, the latter being just another form of violence. A.N.: In your approach to the project, we can clearly distinguish a leaning towards issues of sustainable development, towards the "ecological" dimensions, which you claim are central to territorial development. Can we go even further, do you believe that the progress of cities will lead to a rehabilitation of the social fabric? P.K.: The issue of density is at the heart of sustainable development. All the solutions designed to make an isolated dwelling more environmentally friendly are just misleading attractions. A detached, detached house has three times the energy losses of a neighboring house and consumes on average 10 times more land than a collective dwelling. Clearly, issues of sustainable development, urban ecology, environmental quality and energy consumption habits in our homes remain key. In France, renewable energies account for less than 8% of all energy consumed and housing consumes 40% of all energy. Consequently, and in view of the decline in fossil fuels, this issue will become increasingly sensitive and important. However, while issues of sustainable development should appeal to the pertinence of design, we see that the prevailing vision is a technocratic and demagogic approach, at odds with common sense. It is therefore up to architects to approach these subjects critically and meticulously in order to make sense of them. This is a great challenge for our profession. A.N.: One of Marguerite Duras' characters claimed to be teaching the history of the future. Do you feel, as an architect and urban planner, that you are also teaching a history of the future? Could you tell us what it looks like? P.K: Architecture is considered by law in France as a profession of public interest. This implies that our work is put at the service of a certain idea of common interest and that we take an ethical and political stance. Unlike all other forms of artistic creation, architecture imposes itself on everyone in a sustainable way. All this should require architects to be modest, but also generous and forward-looking. And not, like Max Thor, in Detruire dit-elle, to put us to sleep, but to wake us up. The carousel plan, drawn up by Hippopodamus of Miletus in the 5th century BC, is the spatial retranscription of a democratic principle of impartiality, presumed to allow equal representation of all citizens before the law in the city. In the same way, we could say that, as Andrea Branzi has argued, the New Charter of Athens represents Keynesianism translated spatially. And that the pavilion-like, petty bourgeois suburbs around cities are the expression of an indulgent, individualistic and indifferent society of 'every man for himself' and 'every man for himself'. The city, the public space (or its absence) is a mirror of the societies that create them. The future history of our cities will depend on the choices of the society we make. A.N.: Do you think that the architectural profession is in crisis, that architects are overwhelmed by increasing constraints, by a formative vision? P.K.: I think our society is in crisis... and architecture is part of society. The increase in constraints, regulatory approaches, the tendency towards hyper-specialization, individualism, the relentless pursuit of profit, make it difficult to practice our profession. However, never before have our societies been more complex, and the architect - one of the professionals best trained in mastering complexity. A.N.: Is it possible, from this point of view, to question the role of the architect in the world, in a political and social context, his relation to time, to the concrete, to the immediate; do we really need, in the end, to return to an ethical vision of architecture, for which you advocate in any case? P.K.: You are quite right, it is not only possible, but necessary and indispensable to return to an ethical, political and social vision of architecture, anchored in reality. Without it, architects will be façade designers, ornamentalists or decorators. After serving power and money throughout history, for more than a century architecture has been at the service of the many to become democratic. In a world in constant transformation and confusion, this community project should continue. A.N.: You are president of the Société française des architectes (SFA), honorary member of the Korean Institute of Architects (KIA) and director of the publication "Le Visiteur". We would like to know more about the special issue that Le Visiteur is preparing for Bucharest. Can you tell us what is at stake, what are the requirements? P.K.: We are at the very beginning of an editorial process to really realize a special issue dedicated to Bucharest. Richard Edwards is the initiator of this project, supported by the French Institute in Bucharest and the Romanian Cultural Institute in Paris. The magazine "Le Visiteur", published by the SFA, is not a current affairs publication, but a critical magazine with a very demanding editorial content. It is in this sense that we want to approach the special issue. An important exercise of selection, critical analysis and editorial content is still to be done. Bucharest is a fascinating city with enormous potential for transformation, assimilating a remarkable heritage from different periods. Our aim is to express all this, but also to publicize the most interesting aspects of contemporary architectural production. |

| Note: 1.Quote from the lecture given by the architect Pablo Katz at the French Institute in Bucharest on April 11, 2012. |

| * Pablo Katz is an architect and urban planner. After years of experience in Argentina, he created GKP Architecture in France, then Pablo Katz Architecture. He has realized more than 2,000 dwellings, numerous schools and day-care centers in Paris, the Périgueux Congress Center, the Dordogne Departmental Communication Center, the restructuring of a 15th century building for the Rhinem Opera, and other urban planning projects. Pablo Katz has taught at Camondo School (Paris), UTDT University (Buenos Aires), FADU-UBA (Buenos Aires), Special School of Architecture (Paris) and Kunstakademie (Stuttgart). |

| "A small house, a small garden, can be the object of the dreams of someone who has nothing. But is it a question here of flattering the thoughtless desires of ignorance? " Jean Baptiste-André Godin, Social Solutions, 18711 |

| Alina Nechifor: Your lecture in Bucharest, as part of the Ateliers Libres d'Architec-ture analyzed urban dissolution - more precisely, its title was: 'A small house, a small garden. La dissolution de l'urbain" - an ironic title, as you have already made clear. Could you expand on this concept in a few lines? Is this urban dislocation linked to an excess of individualism, to the fact that each one of us dreams and projects himself in "a small house", isolated, in total independence? What would then be your architectural firm's response?

Pablo Katz: In 1950, there were two agglomerations with more than 10 million inhabitants in the world. 30% of the world's population was urban. Today there are 30 agglomerations with more than 10 million inhabitants and about 500 cities with more than 1 million, while more than half of the world's population now lives in cities. Three quarters of the world's population will be urban by 2025. As a result of this urban sprawl, the total area of cultivated land is being reduced each year by 300 000 square kmp, according to the UN, the equivalent of the surface area of Italy. In France, despite being a developed and dense country with a long urban history, almost 65% of all housing is individual. The peri-urban fabric that is developing in this form bears witness to a retreat from politics, a capitulation of architecture, a lack of vision for spatial planning and the inability of architects to express themselves publicly and make their voices heard. All this is indeed symptomatic of an extremely individualistic society where every citizen aspires to own his own little house with his own little garden. However, this form of urban sprawl is extremely costly for the community: it consumes natural and agricultural land, but it is also costly in terms of roads and infrastructure, due to the low density. Yet, despite their high costs, these proliferating fabrics are completely incapable of producing cities and urbanity. The city is public space and public space is the great absentee from these forms of residential fabric! A.N.: At the opposite end of this mono-functional territory, the pavilion model, we find dormitory towns, devoted to housing and which encourage the contagion of revolt. You support the idea that it is precisely these suburbs of single-family houses, which are sprawling out into infinity, that reproduce (through the mirror effect) the shortcomings and problems found in a dormitory town, that they behave in a certain way like a dormitory town. So the question arises: will we be able to escape violence, isolation? How do you see these things, what would you change to live better? P.K.: In fact, the suburbs, deprived of facilities, services, jobs and leisure activities, behave like dormitory towns, in the same way as a number of large housing estates. However, while it is not possible to bring public transport, facilities, services, employment and leisure to very low-density areas, the density of large housing estates would make it possible. It is necessary to reintroduce a functional and social mix in large residential areas and to rethink their relationship with the landscape. If these large housing estates pose a problem today, demolishing them and replacing them with small detached houses, sending their inhabitants further and further away, not only does not provide a solution but also aggravates the phenomena of exclusion. Only by means of ambitious public policies on spatial planning and urban policy will we be able to escape violence and isolation, which is also a form of violence. A.N.: In your planning approach, we can clearly see the propensity towards sustainable development issues, towards the "ecological-economic" dimensions, which you say are central to the development of territories. Do you believe that the development of cities will lead to a reconstruction of the social fabric? P.K.: The question of density is at the heart of sustainable development issues. All solutions to make the detached house more ecological are a red herring. An insulated detached house has three times more energy loss than terraced houses and consumes, on average, more than 10 times as much land as collective housing. Of course, the issues of the development of the building stock, urban ecology, environmental quality and the energy performance of our buildings are essential. Renewable energy in France accounts for less than 8% of all energy consumed and buildings consume 40% of all energy. From now on, and given the scarcity of fossil fuels, this issue will become increasingly sensitive and increasingly central. And yet, while sustainable development issues should call on the intelligence of the project, we see that the prevailing vision is a technocratic and dogmatic approach, the very opposite of common sense. It is therefore up to architects to take a critical and detailed approach to these issues in order to make sense of them. This is a great challenge facing our profession. A.N. : A character by Marguerite Duras claimed that he teaches the history of the future. Do you feel, as an architect and urban planner, that you are teaching a history of the future? So, can you share it with us; this history of the future, what does it look like? P.K.: In France, architecture is considered by law as a profession of public interest. This implies that we put our action at the service of a certain idea of the common interest and that we assume an ethical and political positioning. Unlike all other forms of artistic creation, architecture imposes itself on everyone, on a lasting basis. All this should require architects to be modest, but also generous and forward-looking. Not like Max Thor in Destroy it says, to lull us to sleep, but to awaken us. The checkerboard plan, conceptualized by Hippodamos of Miletus in the 5th century BC, is the spatial retranscription of the democratic principle of equity, which is supposed to ensure that all citizens are equally representative before the law in the city. It could also be said, as Andrea Branzi says, that the Charter of Athens is Keynesianism translated spatially. And that the suburbs, with their petit-bourgeois suburbs around the cities, are the expression of a liberal, individualistic and disillusioned society, of every man for himself and every man for himself. The city, the public space (or lack of it), is a reflection, a mirror, of the societies that create them. The future history of our cities will depend on the societal choices we make. A.N.: Do you think that the architectural profession is in crisis, that architects are overwhelmed by the contra- inces, by a formative vision? P.K.: I think that our society is in crisis... and the architect is part of society. The multiplication of constraints, prescriptive approaches, the tendency towards hyper-specialization, individualism, the unbridled search for profit, make it difficult to practice our profession. Yet our societies have never been so complex, and the architect is one of the professionals best trained to master complexity. A.N.: Is it possible, from this point of view, to question the architect's role in the world, in a political and social context, his relationship to time, to reality, to immediate data; do we need a return to an ethical vision of architecture, for which you are in any case advocating? P.K.: As you have well understood, it is not only possible but necessary, indispensable, to return to an ethical, political and social vision of architecture, anchored in reality. Otherwise, architects will become facade designers, embellishers or decorators. After having, throughout history, served power and money, for a century architecture has been at the service of the greatest number, to become democratic. This is the societal project that we must continue to pursue in a changing and changing world. A.N.: You are president of the French Society of Architects (SFA), honorary member of the Korean Institute of Architects (KIA) and also director of the publication "Le Visiteur". We would like to know a little more about the special issue, dedicated to Bucharest, that "Le Visiteur" is preparing. Can you tell us what is at stake, what are the requirements? P.K.: We are in the early stages of editorial work to produce a special issue on Bucharest. Richard Edwards is behind this project, supported by the French Institute in Bucharest and the Romanian Cultural Institute in Paris. The magazine "Le Visiteur", published by the SFA, is not an architectural news magazine, but a critical review with a very demanding editorial content. It is in this spirit that we wish to approach the issue dedicated to Bucharest. A great deal of selection work, critical analysis and editorial content remains to be done. Bucharest is a fascinating city with a huge potential for transformation, with a remarkable heritage from various periods. We wish to report on all this, but also to publicize the most interesting aspects of today's architectural production. |

| NOTE: 1. Quote mentioned by architect Pablo Katz in his lecture at the French Institute in Bucharest, April 11, 2012. |

| * Pablo Katz is a D.P.L.G. architect and urban planner. After years practicing in Argentina he founded in France GKP Architecture, then Pablo Katz Architecture. He has designed more than two thousand housing units, several school groups and crèches in Paris, the Perigueux Convention Center, the Dordogne Departmental Communication Center, the restructuring of a 15th century building for the Rhine Opera and various urban planning projects. Pablo Katz has also taught at the Ecole Camondo (Paris), the UTDT University (Buenos Aires), the FADU-UBA (Buenos Aires), the Ecole Spéciale d'Architecture (Paris) and the Kunstakademie (Stuttgart). |

COLLECTIVE HOUSINGParis XIVCost: 10 mil. € excl. VATGeneral contractor: RIVPSurface area: 6.502 sqm ScdDate: 2011

COLLECTIVE HOUSINGParis XXGeneral contractor: FRANCE HABITATIONSurface area: 559 sqm ScdCompetition: 2007

FRANCE BLEU PÉRIGORDPérigueuxCost: 10 mil. € excl. VATGeneral contractor: CONSEIL GÉNÉRAL DE DORDOGNESurface area: 700 sq.m Scd Date: 2006Photo: Hervé Abbadie

HOUSE CK06 Paris XXGeneral contractor: PRIVATESurface area: 250 sq.m ScdStructure: CONCRETE-METALYears of realization: 2006-2008Duration of study: 18 MON MONTHSDuration of works: 18 MONTHSDelivery date: 2009Photo: Arnaud Rinuccini