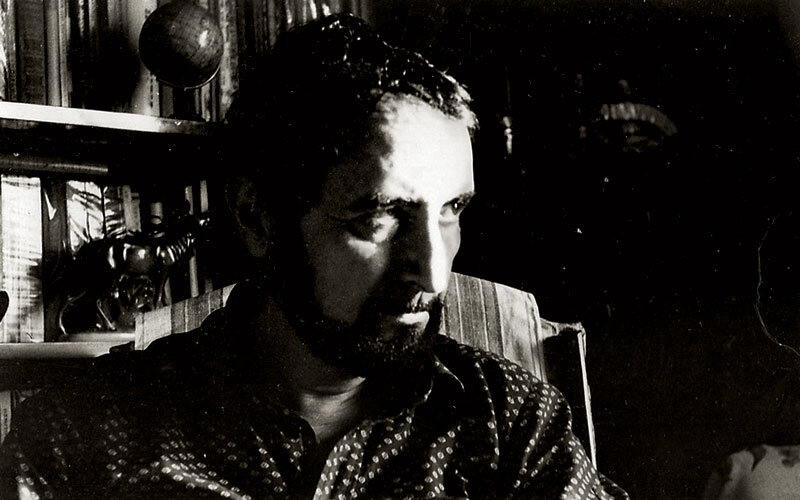

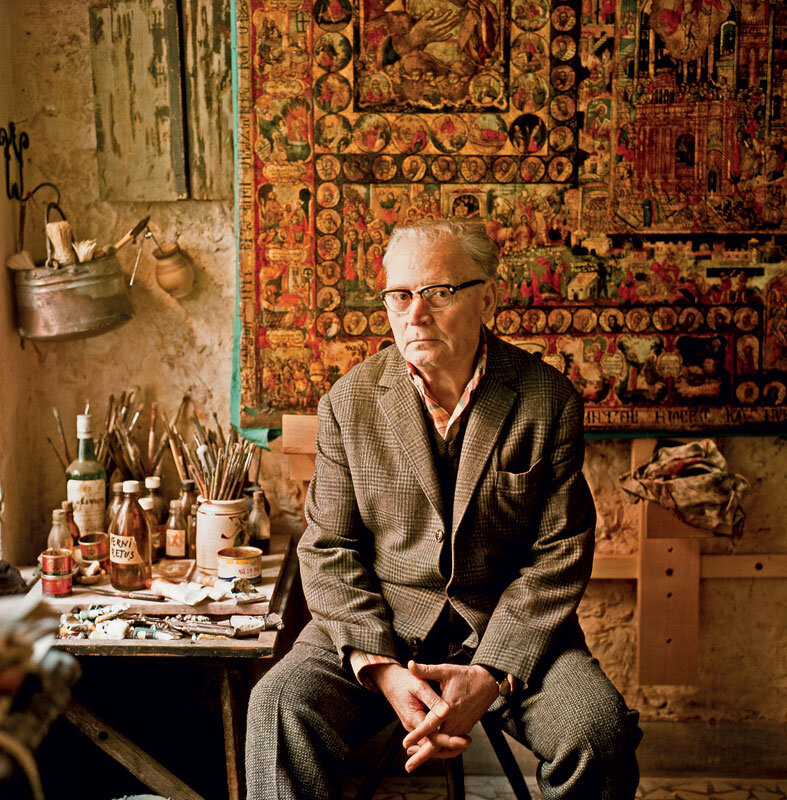

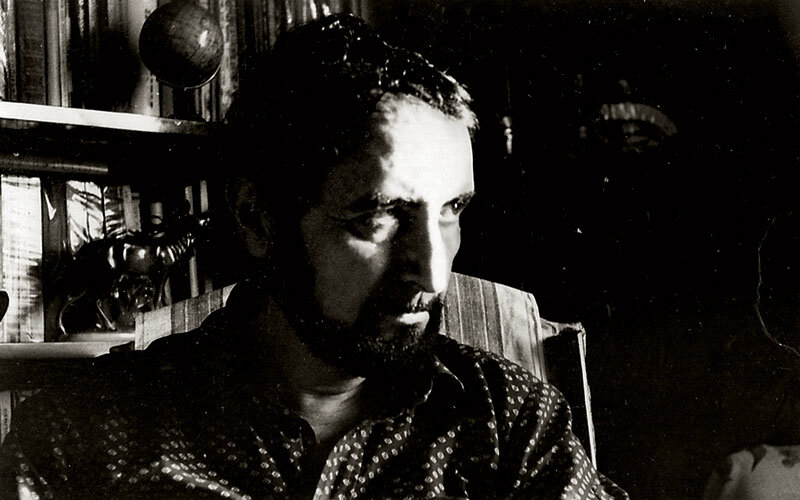

Ion Cristodulo (1925-1991)

1925 - born on October 25, in Bucharest

1943 - graduates from Gheorghe Lazăr High School, Bucharest

1943-1948 - undergraduate studies: Fine Arts (Bucharest), Architecture (Bucharest), Scenography (Cluj)

1947 - scenographic debut at the Giulești Theater

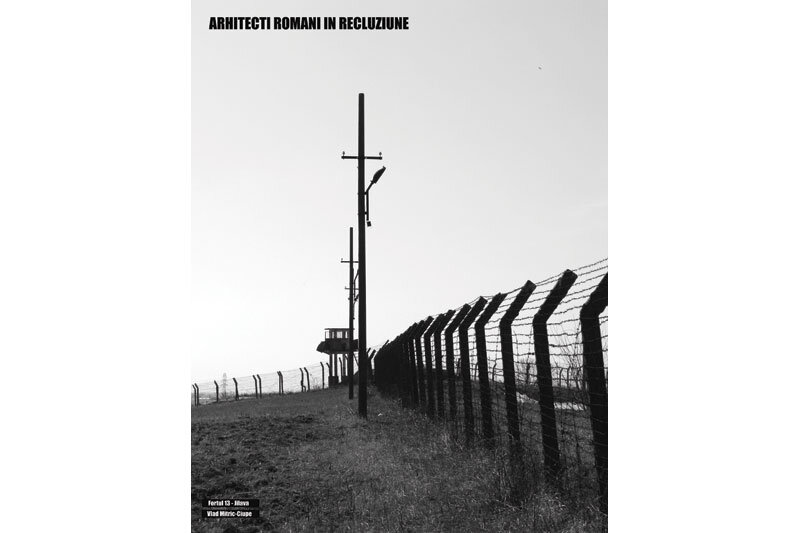

1950-1953 - political imprisonment in Jilava, Canal - Coasta Galeș and Poarta Albă, Constanța - Cazinou

1951-1952 - while in detention, he is assigned as site foreman for the works

restoration of the Constanța Casino

1953 - hired as technical referent and later employed as architect,

at Trustul 3 Construcții, Bucharest

1954 - Romanian Opera in Bucharest, site foreman for finishing works

stucco-marble

1955 - Schitul Maicilor, monumental architecture, execution and finishing works

1955-1958 - Cașin Monastery, monumental architecture, execution and finishing works

1956 - The House of the Spark, monumental architecture, finishes

1956-1959 - Buftea Cinematographic Studios, site manager

1958 - "Sf. Ilie" Church, Slănic Moldova, mural painting

1958 - Agency 1 CFR Bucharest, mural painting

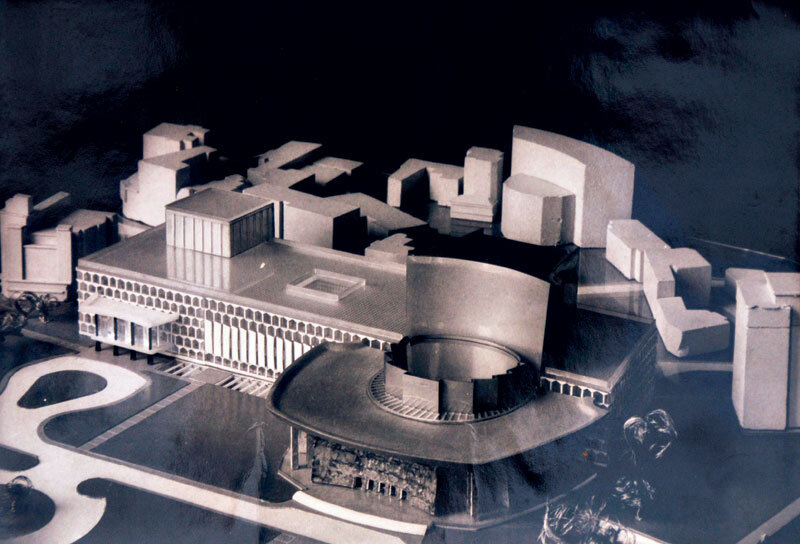

1959 - State Theater, Brasov, monumental architecture, site supervisor

1960-1961 - imprisonment in Codlea prison, sentenced to 5 years, released after one year

1961 - Art Shop, Făgăraș

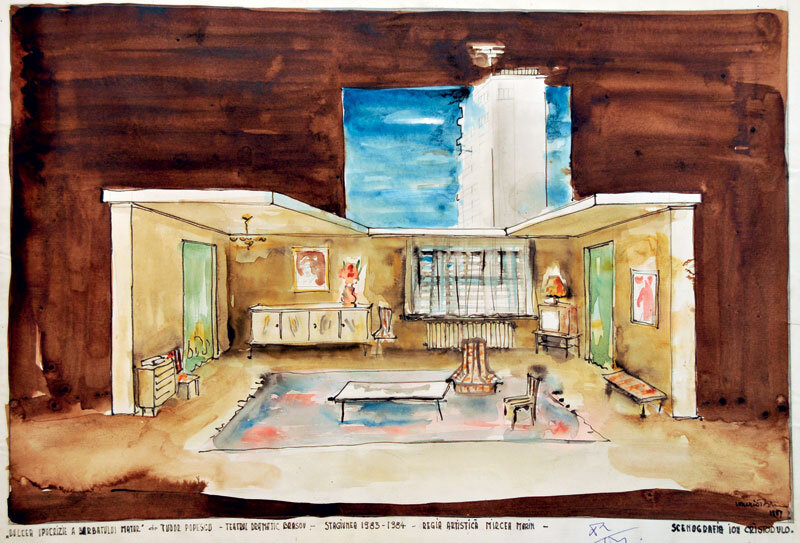

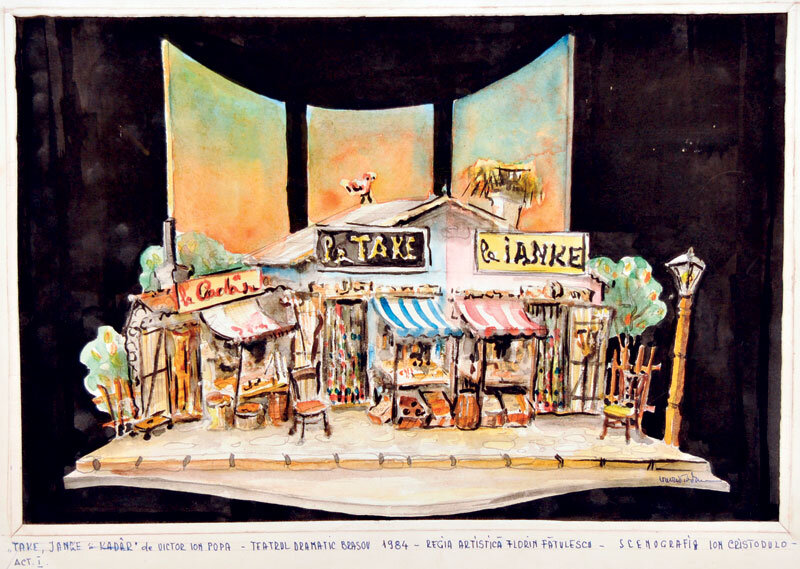

1962-1989 - Dramatic Theater in Brasov, stage designer

1991 - died on September 8

Coming from a family with strong roots in the Christian life of Greece, with grandparents and great-grandparents who were Orthodox priests, a family that took refuge in Bucharest at the end of the 19th century, Ion Cristodulo1 followed three courses of study between 1942 and 1949: architecture, fine arts and stage design. During the war and the early years of the communist regime, his life was marked by hardship and poverty, and he worked hard to support his family. He supported himself by performing at the National Theatre, and then took a job as an artist-decorator at the CFR Trade Union House of Culture. With the desire to continue his studies abroad and to go to Italy - he had been confirmed as a potential candidate for an architecture prize2 - he joined the Greek Orfeus Society and the Pro America-Britain organization. His first political grievances emerge amid the transformations

Romanian society and he became active in a "monarchist subversive organization" - the Mountain Eagles - which called for resistance actions against the regime. We do not yet have all the information about these activities of the architect, but on the one hand, the documents in the CNSAS archive prove a tough investigation in the cellars of Rahova, and a house search report identifies in Cris-todulo's possession a model 27 pistol, cartridges of various caliber, a firecracker and a rocket. Neither in the course of the investigation nor in the verdict do we find any reference to these items of evidence, which shows the investigators' inability to prove anything concrete3.

We learn from a note in his father's diary4, saved and recovered decades later: "On May 29 (1950 - n.n.) our dear son Neluță was kidnapped from us by the Securitate and taken away in the torture and suffering cellars, leaving a huge void in our crushed souls". His wife was pregnant at the time, and in a few months' time her first child would be born, whom he would see after his release5. He is attached to a batch of 15 members and convicted of the offense of spreadingforbidden publications6. The very harsh investigation is also proven by a note in the file: "he is insincere, he has given his statements with great difficulty and only in the face of the evidence" - for those familiar with the methods of the Securitate: daily beatings, physical and mental torture, etc.

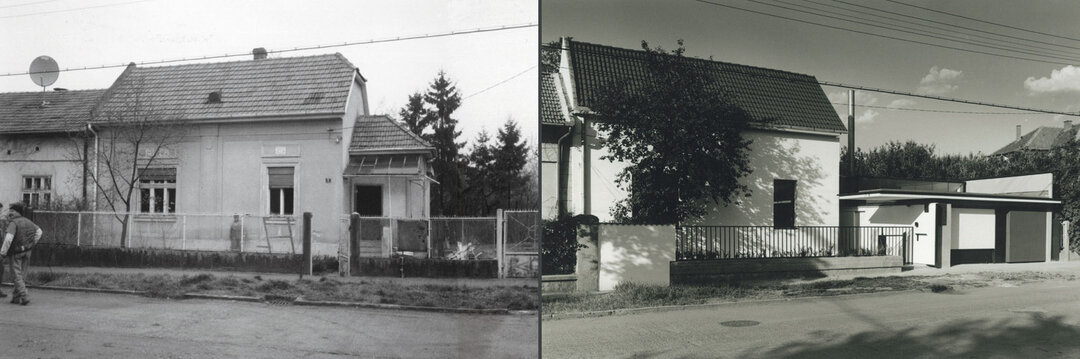

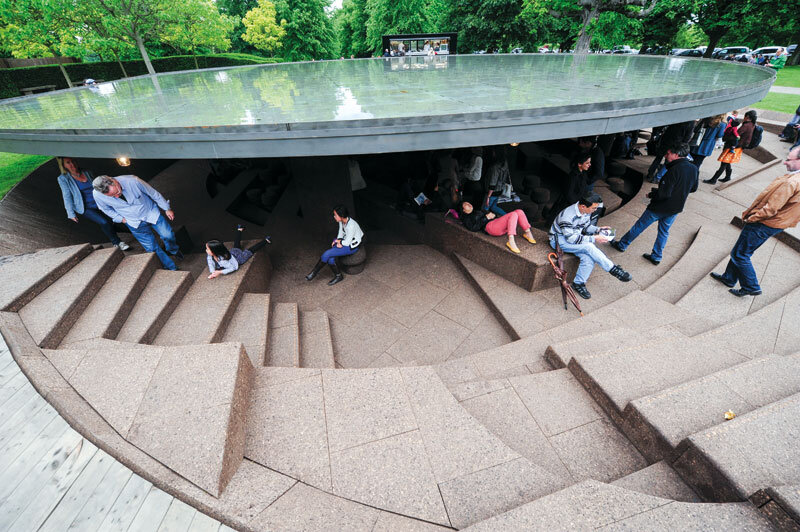

After a period spent in Rahova transit prison, he was transferred for a few months to Jilava prison7 (in July 1950), and then sent for "re-education through labor" to Canal. The work at Coasta Galeș consisted in unloading and loading by hand wagons with excavated earth. Working hours were 12 hours a day, in two shifts. The work did not stop even in winter, as excavating the frozen earth was anordeal8 .The most important moment of the concentration camp experience was the selection of a batch of 100 men picked up in the fall of 1951 from the Coasta Galeș camp9 and taken to Constanta to restore the Casino, destroyed by bombing during the war. While for the first two months the work was "supervised" by the architect Constantin Joja10, Ion Cristodulo was in charge of the site for the following year - until completion. More than 60 years after this event there is only one surviving witness, the former political prisoner Mircea Nicolae11. Pious and moving - a "simple" apprentice printer at the time of his arrest - Mircea Nicolae says today that prison was his opportunity for "higher education" alongside so many intellectuals, and that his survival was due to the fact that "they had each other and all together they had God"12. When talking to his son about the episode at the Casino, Ion Cristodulo referred to it as his own Chateau d'If, and the actor Ion Omescu - another of the 100 apprentices - calls the prisoners knights of pale faces/ with little power but gentlefaces13 .

After a further period in the Poarta Albă camp14, Ion Cristodulo was released in 195315, but not before signing the standard pledge for those leaving the prison. On my release I was informed that I was not allowed to divulge to anyone anything I had seen or heard about the places of detention I had passed through, or about the people incarcerated. I will also not communicate anything written or verbal to relatives or other persons about the remaining prisoners. In case I do not comply with the above, I am aware that I am liable to suffer the rigors of the laws of the Romanian People'sRepublic16 .

Serving a three-year sentence, which came at the heart of the most brutal period of political imprisonment in Romania (when the process of extermination and re-education of the enemies of the people took unimaginable forms), the architect Cristodulo is released as another man, a man who was perfect in prison from the perspective of faith and hope. As an example of unshakeable faith, which, in the ruinous decades of human hardship, has ensured that hope never dies and that grace endures and flourishes unceasingly through his chosen ones, making the broken to beunconquerable17, are the few lines he tries to send from prison to his son, which reach their destination a few years later. My child. Today I will tell you a sad story. It is the story of the land of no joy and your father is now among them. Those who grow up there are many and ugly. The land is without water and the days without feast. There are cars that scream louder than people and mountains of sand made with the palm of the hand. Under them we have lost our souls. We're all learning and always something else. I have learned to be silent. You learn to talk. Look, there's the table and the chair and everything. We're almost there. One day you'll pull me by the coat and say, "That's Dad. Life's a ship, my child, and the winds are ill, but let the sail be always white.

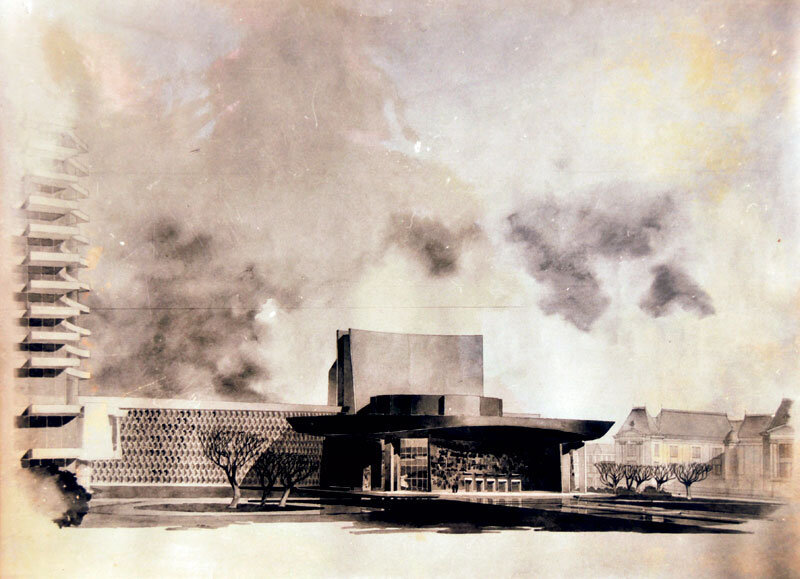

Outside he finds a radically altered world, overturned values, the key to Marxist dialectics present in every field, a powerful alter-rare, including the architects' guild18. Submissive to socialist realism and strongly conditioned by ideology, the architecture of the time took a strong stance against cosmopolitanism and bourgeois imperialist architecture. Under the simplifying pretext of the need for an art intelligible to all, which justified limiting expression to a single formula, hostility to artistic diversity was clearlyapparent19 .

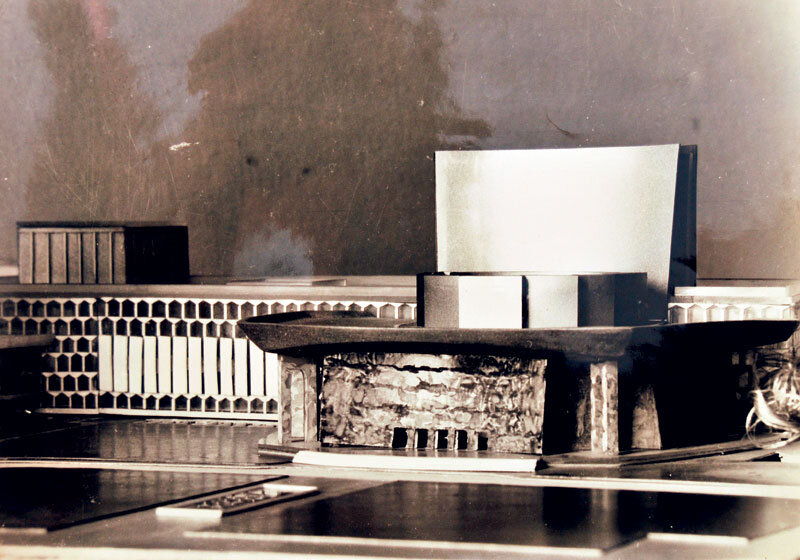

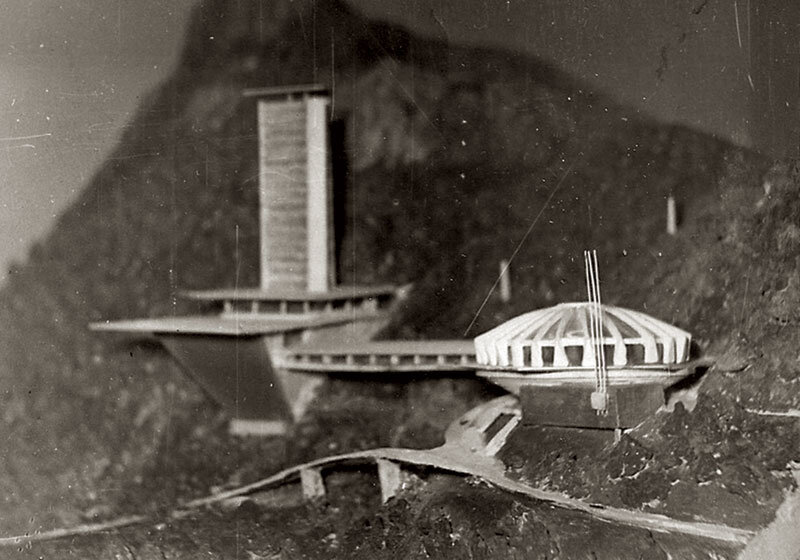

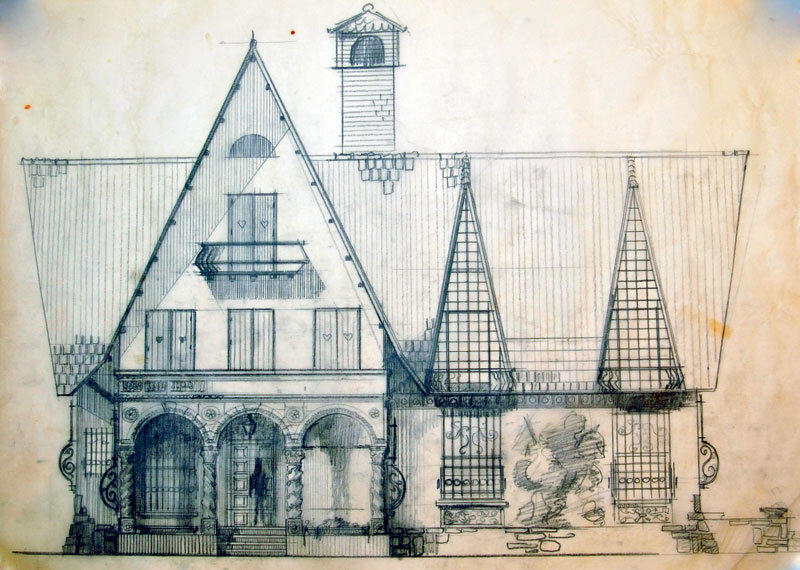

In this turning point in Romanian architecture, Ion Cristodulo found it very difficult to find a job, and after six years of participation in various architectural, restoration, stonework, stucco work, church frescoes, in 1959 he was entrusted with the completion of the State Theatre in Brasov - one of the main landmarks of his work as a monumentalist architect - in particular the interiors and, especially, the ceiling of the main hall bearing the imprint of Cristodulo's talent and skill. Following a slanderous denunciation, accused of damaging the State during the management - including financially - of the works at the Theatre, and benefiting from aggravating circumstances due to his previous convictions, he is sentenced to 5 years in prison. His father's diary describes the scene of the trial: "In the dock, between the sentenced, was my dear son in prison uniform, weakened by the pain and moral suffering he endured in the Codlea prison. The sight of my son in the state he was in crushed me with grief, and I wonder how I had the strength to bear it". Following an appeal, where it was proved that the alleged injuries were mere fabrications, Cristodulo was released after another year in prison. After settling in Brasov, he remarried and took a job as a set designer at the State Theatre, where he designed sets and costumes for over 50 performances. Over the years, he also participated in the staging of other plays, operas and operettas in Bucharest, Iași and Alba Iulia, and was the set designer for the first four editions (1968-1971) of the Cerbul de Aur International Festival. After the trauma of imprisonment, he tried to find a form of balance by taking refuge in painting20. His more than 60 paintings, along with sketches, studies, stage design and architectural works, complete the personality of a complex artist with a dramatic and impressive career. The sufferings he endured, the stigmatization that followed his liberation, and the dissatisfaction he accumulated after December 1989, when architect Ion Cristodulo was on the streets with the people of Brasov, all hastened his end, which came on 8 September 1991, at the age of just 66. An architect, painter and scenographer with outstanding achievements, all the more so in the context of his "quality" as an enemy of the people, a personality still alive through the work he left behind, and one of the architects imprisoned, whose fate we are now considering. Finally, we would like to mention the special interest and support of the architect's descendants, who have provided us with material from the family archive, and their initiative to publicize the life and work of the father, first through an exhibition of paintings, and in the future through exhibitions dedicated to his architectural works, scenography, photography and a complete monograph.

Notes

1. Greek surname which, in translation, means the dog of Christ or, by extension, the servant of the Lord.

2. Interview with Apollon Cristodulo on January 13, 2012, author's personal archive.

3. As a result of the tortures to which the members of the lot were subjected during the investigation, the Securitate failed to prove the "terrorist" character of the organization, contenting itself with the "subversive" one.

4. Found in the personal archive of Mr. Apollon Cristodulo, one of the architect's sons, as well as all the illustrations in this article.

5. We also mention the victimization of the wives and children of political prisoners, confiscated wealth, and crossed career paths. Most probably as a result of pressure from the Securitate and the peculiarities of the situation, the wife divorced the architect Cristodulo in 1953.

6. The 16 convicted were aged between 22 and 52 and received sentences ranging from 1 to 10 years, architect Ion Cristodulo was sentenced to 2 years in correctional prison.

7. At Jilava he was cellmate of: G. D. Ioanițescu (university professor and minister), Generals Leonard Mociulschi and Gheorghe Mihail, intellectuals Ion Halmaghi, Camil Petrescu, Zahu Pană, George Ivașcu, and Father Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa.

8. Dicționarul Penitenciarelor din România Comunistă (1945-1967), IICCR, Muraru Andrei (coord.), Polirom Publishing House, 2008.

9. The architect Cristodulo worked in a team of loaders-unloaders that included the priests Arsenie Boca and Ilie Lăcătușu.

10. Architect Constantin Joja (1908-1991), sentenced in 1948 to three years in prison, is the subject of a future episode of our series.

11. Mircea Nicolae was 17 when he was arrested for membership of the Partizan Youth organization.

12. Interview with Mircea Nicolae on 16.02.2012, author's personal archive.

13. Poets behind bars, Petru Voda Monastery, 2010.

14. The largest camp on the length of the Channel, with a capacity of up to 15,000 prisoners.

15. Long after the official expiry of the sentence, which indicates recalcitrant behavior from the point of view of the Securitate, those considered re-educated were released on time.

16. One of the reasons why Ion Cristodulo spoke little about his detention period.

17. Ion Cristodulo - painter, architect, scenographer, Apollon Cristodulo publisher, Bucharest, 2012.

18. In 1951, the College of Architects was abolished, the Institute of Architecture aggressively taught Political Economy, Scientific Socialism and Russian, admission was based on a dossier, many teachers and students were expelled from the school, many architects were imprisoned and others were purged, the first design institutes appeared, which meant the decapitation of the liberal profession.

19. Union of Architects of the P.P.R.R./R.S.R., Archives of Totalitarianism, Romanian Academy, National Institute for the Study of Totalitarianism, issue 3-4/2010, p. 234.

20. Homage exhibition, 22 May-8 June 2012, organized by the Calderon Cultural Centre of the City Hall of the 2nd District in partnership with the React Foundation, TVR Cultural, at the initiative of the sons of the architect Cristodulo.