Bitolia Red - A long-liver on the painting scene

On the occasion of the retrospective dedicated to Alexandru Țipoia five years after his death, Amelia Pavel announced the provocative approach of new classifications of artists born between 1914 and 1920. Her suggestions changed, with interest and perplexity, even the selection of the National Gallery of the Art Museum.

It is also five years since George Ștefănescu, who has been in exile near Münster since 1989, stopped painting. It is not only the same year of birth, 1914, that brings the posthumous destiny of the painter Ștefănescu closer to the exemplary reconsideration of Țipoia's work, carried out by his son after 1990. Both artists have Macededo-Greek paternal roots. Both served a formula of balanced modernism, Țipoia predominantly in formal rhythms, Ștefănescu in chromatic arpeggios. The work of these "little masters" can always call into question the stars of an epoch, through exegetical revisitation subordinated to a revelatory display. The surprise comes through a new filter of stylistic coherence, especially when the artist has opted for discretion and the penumbra of his own studio. And in the game of market shares, works that stand the test of time (in terms of execution technique), have an added historical authenticity and an originality untouched by mediatization, can delight as a restored novelty and can broaden the panoptic destiny of the artistic vocation on the canvas of a historical era.

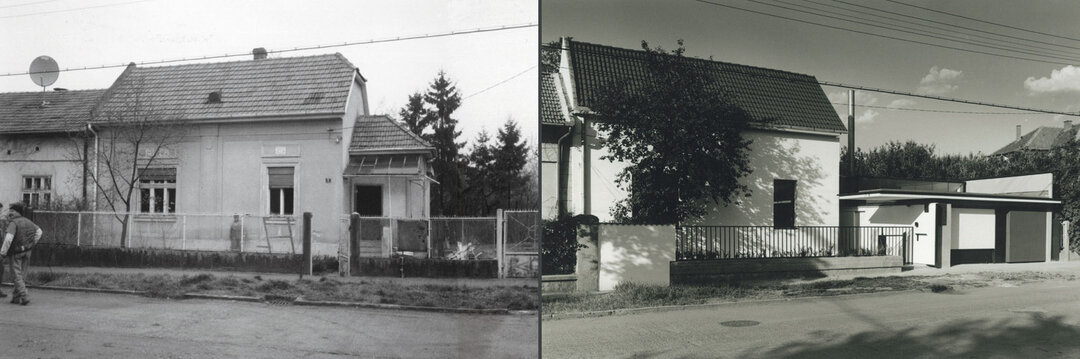

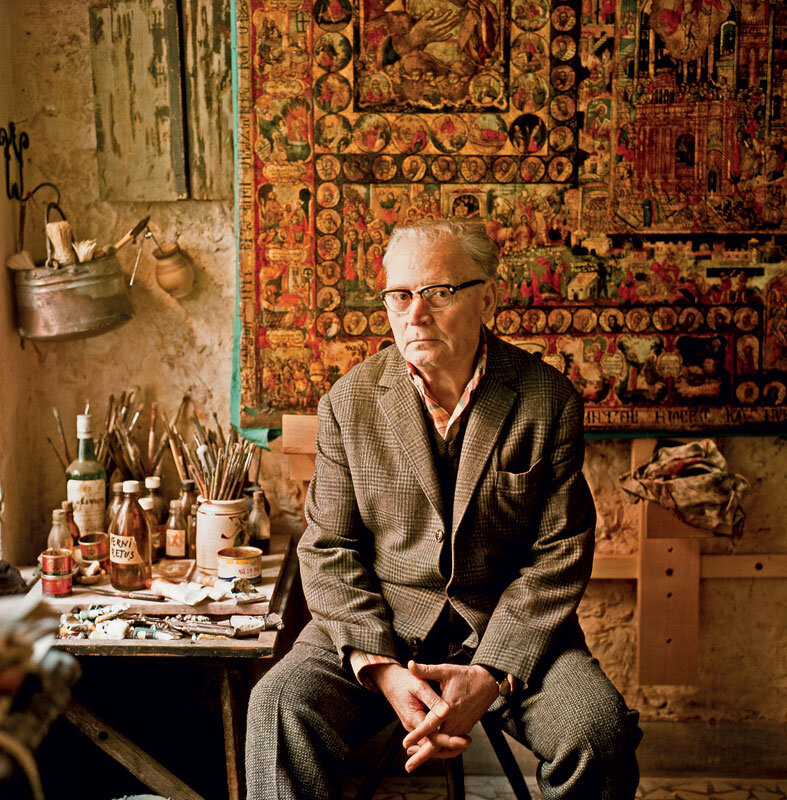

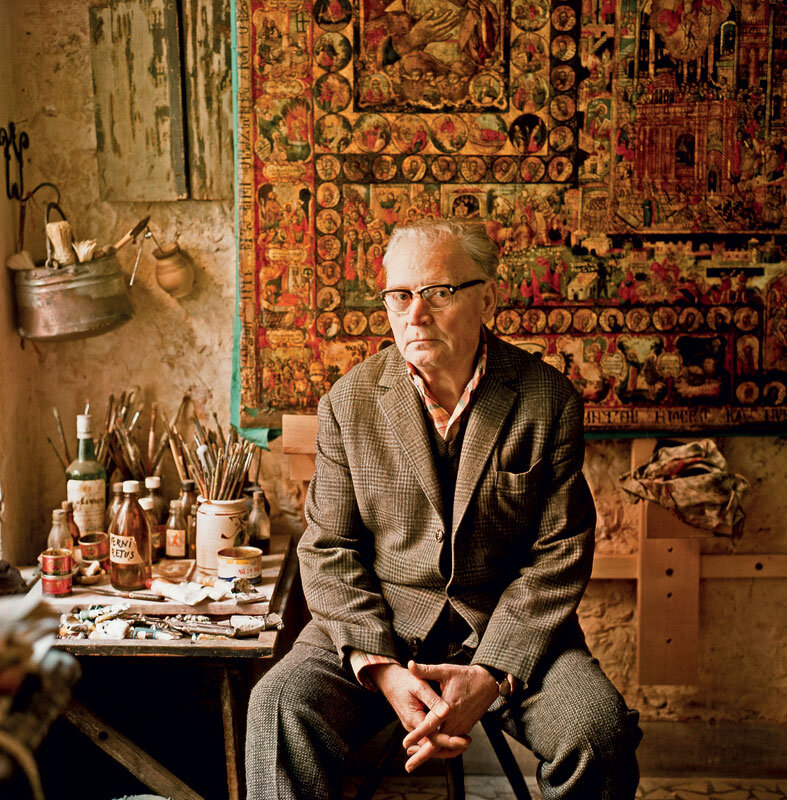

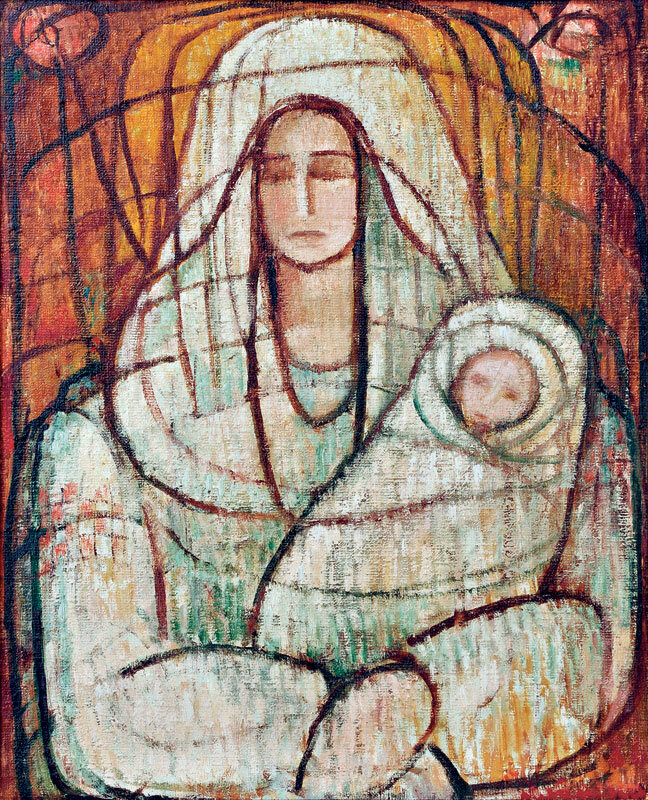

Until the age of 50, George Ștefănescu did not have the peace and quiet of a quiet studio for the 'certificate of modern cerebrality' that the demanding Anca Arghir awarded him in Arta magazine, in reference to his exhibition at the Simeza Gallery in 1970. His destiny as a painter was forged during his school years in Râmnicu Sărat, then, from 1933 until his mobilization at the front, in the environment of Theodorescu-Sion, Lucian Grigorescu and, above all, Nicolae Dărăscu. But the earthquakes of the mid-20th century directed George Ștefănescu towards various artistic expressions with a concrete outlet: painting and mural decoration, advertising graphics, posters and, above all, stage design. His work for the theatre (1958-1974) replenished his dexterity for strong color, a sensitivity that had been compromised for about a decade after the physical trauma of the war. George Ștefănescu left his son, an architect and painter, hundreds of easel graphics and paintings. The artist was stylistically analyzed in the monograph published in 1987 by Meridiane (signed by Adriana Bobu), in the key of a harmoniously tame expressionism. Not at all ostentatious, the painter captures an extended cone of stimuli-pretext from reality for a stylized figuration in arched and nested forms like a composition for enamels. More than just a landscape painter, Ștefănescu is an imaginative with parabolically composed figures (meditative themes, harlequins, dance, folkloric customs) that can be sublimated into chromatic graphs, well mastered in the realm of lyrical abstraction. On the other hand, still lifes or toponymic landscapes can gurgle with the pretexts of ripe chromatic families and contour arabesques. "The Mystery of Blue" is the title of an oil canvas from 1983, but perhaps the red of an old Balkan carpet is a leitmotif of George Ștefănescu's stenic chromaticism. It is sensuous with the enamel of the painting, but also honoring the contours of the form, in a kind of dejucado-desplete way.

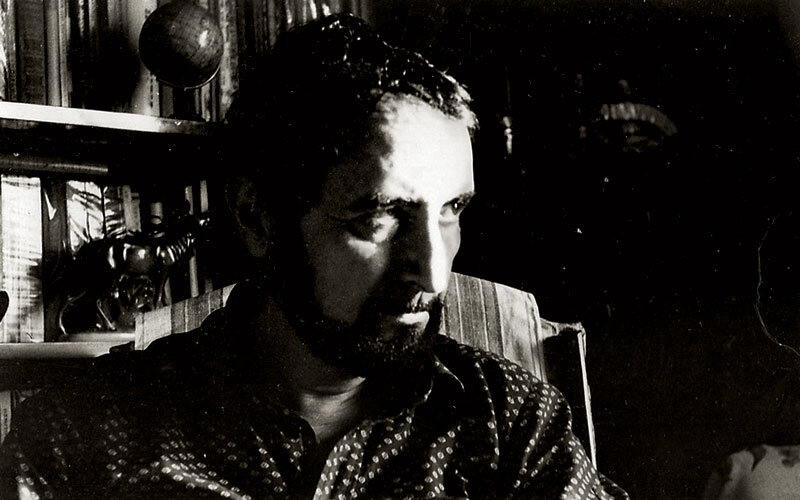

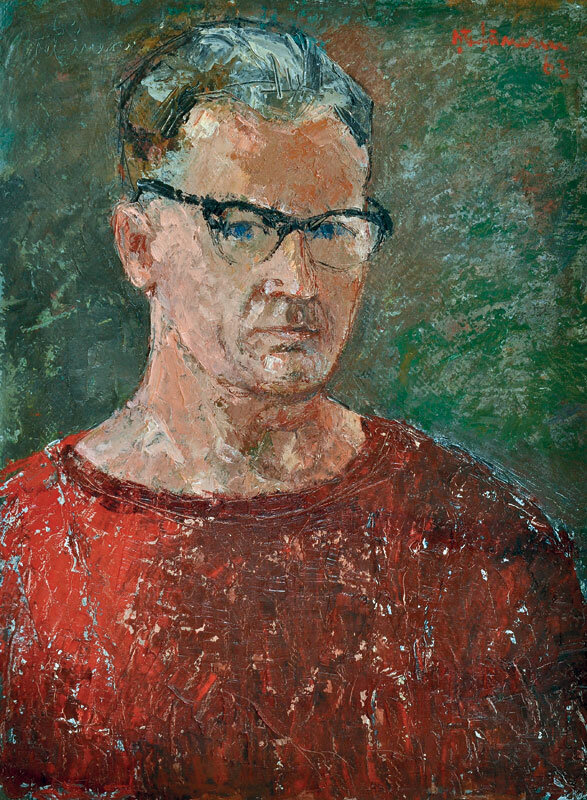

The painter's sadovenian style appears meditative-concentrated in his remarkable self-portraits, of the man born in the Great War, seriously wounded in the Second World War and able to see the United Europe. The long-lived artist is a marvelous example of seniorial senescence fueled by an artistic destiny that has conquered the evil of the times, that "Sadness of Young Women" of the middle of the 20th century.

Photos: Radu Ștefănescu