Cezar Lăzărescu, the story of an architect

There is no doubt that a simple listing of the works under the signature of Cezar Lăzărescu could cover the entire space of this article. It is equally true that in just as many lines one could gather the comments, misgivings or accusations against Cezar Lăzărescu's public persona. However, a balanced assessment of the author and the period in which he evolved cannot yet be made. Until then, it can be said that Cezar Lăzărescu was an extremely prolific architect with a long professional career. Nor can it be denied that the architect had a dual relationship with the communist regime, alternating between protected and disadvantaged. Without going too far wrong, it could be said that the life and career of Cezar Lăzărescu could have been a good source of inspiration for a volume that follows on from George Călinescu's companion novels, Bietul Ioanide and ScrinulNegru1. Thus, if Ioanide's fate is an exemplary illustration of the architect's destiny in the context of the changing political regime of the 1950s, then Lăzărescu's case can continue the story, illustrating in an exemplary way the architect's evolution as a professional and public figure throughout the entire communist period.

In the following, the personality of Cezar Lăzărescu will be presented with the help of a fictional character. As the thread of reality is doubled by the references in the footnotes, the concrete facts are placed in the background of the text, offering a double reading.

The sketch of such a character might sound like this:

Baltazar Lăzărescu, illegitimate son of the architect Ioanide

He had always felt that fate had been unjust to him. He had felt a burning desire to renounce his own name from the moment he learned that Alexandru, his beloved and mournful father, had been his adoptive father2. As far as he could remember, he had seen Ioanides only once, and it seemed as if he could still hear in his ears that strange way in which he had spoken his name. The architect had said to him then, "Balthazar, the patronized king! What a beautiful name you have, my boy." He thought he recognized him in public at the watercolor exhibition. Ioanide, ebullient, was giving explanations about the watercolors on display, looking proud, as if they were his own works in the exhibition3. And then, for a while, he heard nothing more about the architect. He met him again later, in his second year at university, when one of his colleagues introduced him to the man who was to teach them the history of architecture. "Here's Ioanide, the great professor!" The tone of his voice was wry and ironic. Although considered by many of the students to be a character of unbounded coldness, Balthazar will always remember a warm, gentle and understanding Ioanides. For Baltazar, contact with Ioanides meant not only rediscovering his lost father, but also discovering the fundamental truths on which he later built his own path in architecture4.

From the very beginning something had pushed Baltazar towards leftist thinking and he had done so with real faith. However, from the very beginning he had the childish satisfaction of being in the opposite camp to that of Tudorel, Ioanide's eldest son5. He had joined without batting an eyelid those who wanted to be in step with the times and make their contribution to building the new society. Although he had not yet finished university, Baltazar had enrolled in the school of town planning and there, together with some of his colleagues, he practiced town planning under the guidance of some of the masters of the time6. Very soon afterwards, Baltazar began his real career designing for the country's major reconstruction works. He had been involved with great impetus, as an employee of the new Construction Design Institute, in drawing up plans for residential and administrative buildings in one of the most important industrial cities of the time7. The young architect would later go on to design large-scale urban compositions in the spirit of socialist realism for future socialist cities in the south of the country; from now on, Baltazar could take pride in the fact that he was working alongside his father8.

From the very beginning, Baltazar had been fascinated by Ioanide's clear mind and the skill with which he put his thoughts on architecture on paper. Although at first rather technical articles, reports of projects in progress, Baltazar's texts seemed to have both clarity and thoroughness. Writing tidies the mind, Baltazar later told himself9. The new architect was thus beginning to make a name for himself, even in the anonymity into which the emergence of the design institutes had plunged his profession: his articles appeared in the magazine alongside those of Ioanide10.

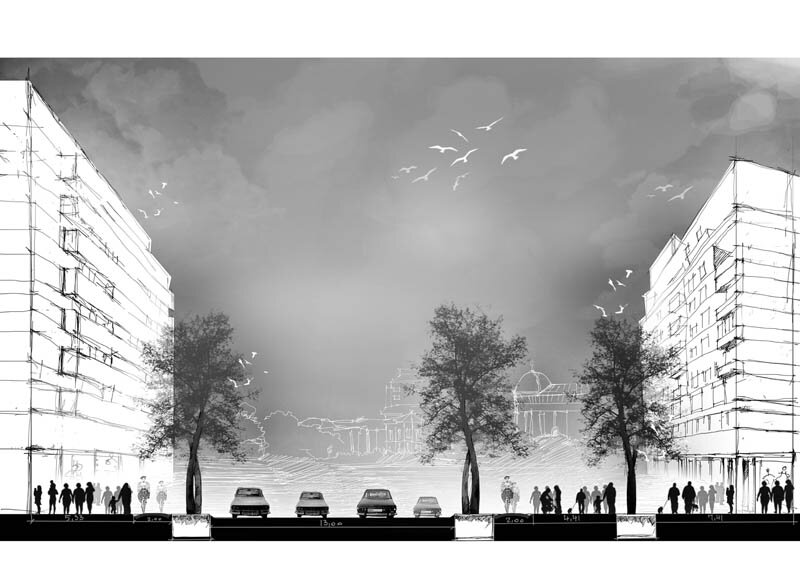

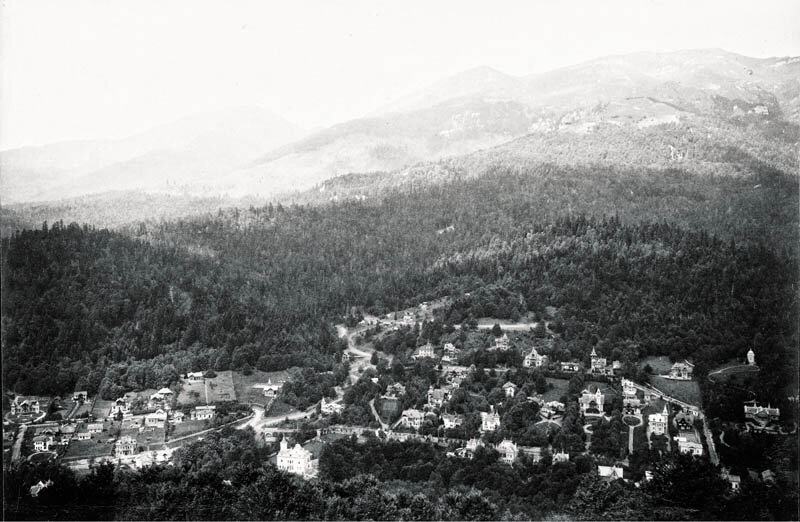

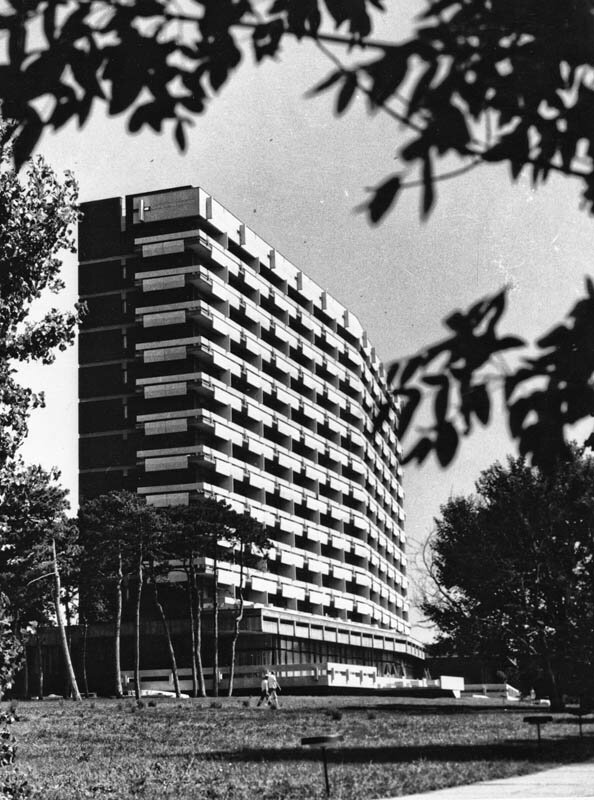

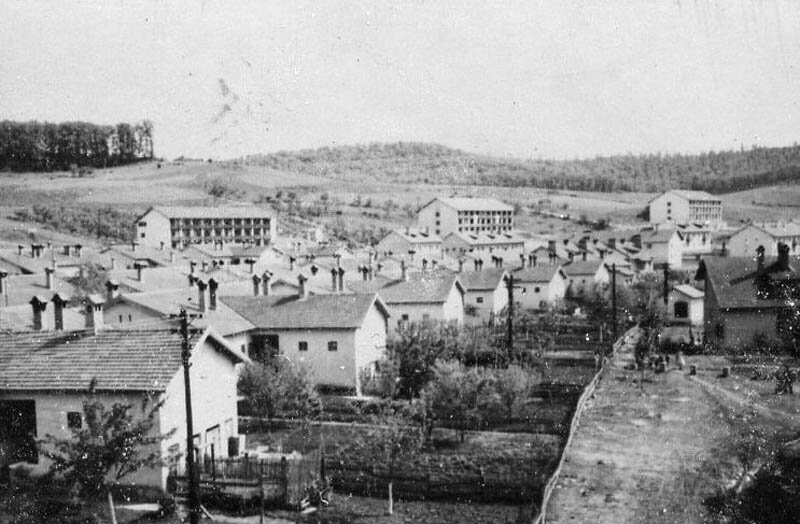

In the last years of the troubled post-war period, Baltazar, a young architect who had proved himself to be a good coordinator, was given the task of systematizing the coast11. Having abandoned the canal project, the political regime was now looking to fulfill another promise: raising living standards. The seaside was also to be a common good, the land of dreams. It was only now that Balthazar felt his career had truly begun. After a brief period still trapped in the method of Socialist Realism, Baltazar gave free rein to his imagination, freeing himself from the constraints of traditional urban planning, with streets enclosed between corridors, even if they were bordered by low-rise blocks12. With the seaside projects, Baltazar was breaking away again from Ioanide; now it was he, the son, who would show and teach the old architect the beautiful, the new. At least that was what Balthazar thought at the time, full of enthusiasm and pride. But it was the hubris of an architect who, at only 38 years of age, was receiving all the official merits due to him13.

From now on, the projects would flow and Balthazar's path seemed paved with gold. But fate did not spare Balthazar either, just as it had for Ioanides a few years earlier. Balthazar's refusal to design a traditional-looking dwelling and abandon his new creed brought the architect into disgrace for a while14. He was again in his father's shadow.

For a while, however, Ioanide seemed to have lost the strength of his youth, and when fate brought them face to face again, it was the ambitious Baltazar who won the day15. And again the projects flowed: hotels, residences, embassies. Baltazar was now a professor at the Institute of Architecture and had very soon been appointed rector of the Institute. Again known and protected16.

Times were, however, changing with astonishing speed and what had been right yesterday was now defied. With time, Baltazar realized that politics is a spinning wheel, coming to the same point from time to time, whether you like it or not. So when he was asked to emblazon his own ideals, he kept silent, thinking back to his youthful years17. Only two years before his death, in his capacity as President of the Union, he replied curtly and jerkily to the reporter interviewing him, without even listening to the latter's questions: "The creation of contemporary Romanian architecture is based on the powerful political, social and, above all, economic transformations that have taken place in our country since the Second World War. The new social order and the intense process of industrialization of the country led to..."18. To Balthazar, the words echoed in his mind in a strange, old-fashioned voice, like a long-learned poem. Although he thought he had much more to say, when the wheel would have turned, Balthazar died suddenly, much earlier than Ioanides19.

The sketch of the imaginary character Baltazar Lăzărescu - Baltazar Ioanide, after the name of his natural father - is pure fantasy. However, it attempts to highlight precisely the "professional" paternity that the mature architects of the inter-war period had over the generation of architects to which Cezar Lăzărescu belonged, despite the political regime they lived through. Cezar Lăzărescu's professional destiny traversed the (so diverse) stages of the communist regime in the same way that the professional career of architects such as Duiliu Marcu, Horia Maicu or Octav Doicescu crossed diametrically opposed political regimes, adopting or adapting to their own expressive language. Baltazar Ioanide's story also speaks about the particular destiny of architecture and, implicitly, the role of the architect in communist society, as they were officially exhibited, but which lost their meaning altogether, whenever they intersected with manifestations of the cult of personality.

NOTES:

1 Poor Ioanide and The Black Scrin are the two novels written by George Călinescu in the spirit of socialist realism.

2 We know of not the slightest doubt as to the authorship of Alexandru Lăzărescu, and it is not our intention to allude to it in the slightest. The distortion of reality in this way is the pretext of this exposé by alluding to the fact that a person born in 1923 could very well have been the son of Ioanide, whose date of birth is identified by Mariana Celac as 1887 [Mariana Celac, "B. Ioanide, architecte (1887-1968). L'homme et l'oeuvre" in Secolul 21. Spécial Bucharest-Paris, p. 69-167]. Cezar Lăzărescu was born in Bucharest on October 30, 1923, and his parents were Alexandru and Sofia Lăzărescu.

3 In 1942, the year in which he was admitted to the Faculty of Architecture, Cezar Lăzărescu's drawings and watercolors were exhibited in the small hall of the Athenaeum (Ileana Lăzărescu, Georgeta Gabrea, Vise în piatră, București, Ed. Capitel, 2003, p. 162).

4 Here Ioanide is none other than G.M. Cantacuzino, who at the beginning of the 1940s taught History of Architecture at the Faculty of Architecture in Bucharest. In his book, Ion Mircea Enescu describes G.M. Cantacuzino as a character who showed students "a gratuitous contempt", a professor who "was at the chair to pass on his knowledge to beginners" (Ion Mircea Enescu, Arhitect sub comunism, București, Ed. However, the younger Cezar Lăzărescu saw G.M. Cantacuzino a teacher of dialog (Ileana Lăzărescu, Georgeta Gabrea, Vise..., p. 17). Even if G.M. Cantacuzino was a professor at the School of Architecture for a short period of time (1942-1948), his personality marked those generations of students with whom he came into contact. The equilibrium of Palladio's architecture as transmitted by Professor Cantacuzino to his students was one of the foundations of their formation (see the articles dedicated to the fourth centenary of Palladio's death in Arhitectura, no. 6, 1980, pp. 45-54).

5 We do not know about Cezar Lăzărescu's political orientation during his university years, but it is known that in 1948, after graduation, he joined the Salva Vișeu labor brigades as a volunteer (Ileana Lăzărescu, Georgeta Gabrea, Vise..., p. 162).

6 Between 1943-1948, under the direction of Duiliu Marcu, a department specializing in urban planning was set up at the Faculty of Architecture in Bucharest (Grigore Ionescu, 75 de ani de învățământ superior de arhitectură, studiu monograficfic, București, IAIM, 1973, p. 58).

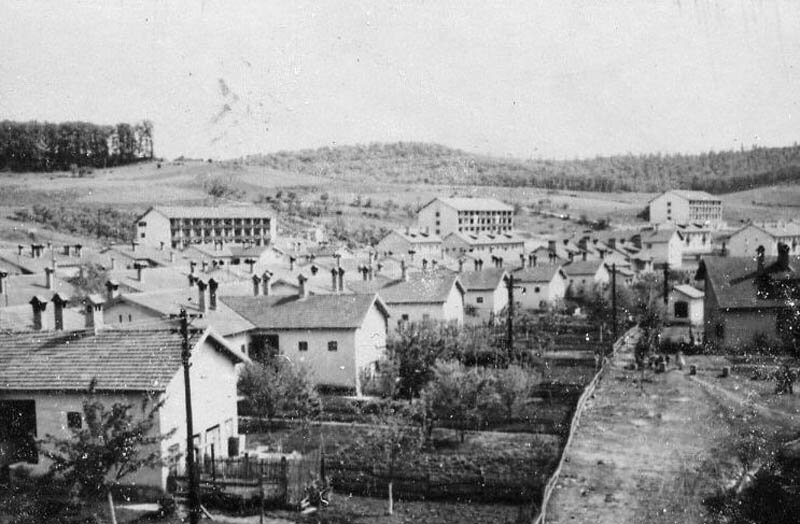

7 Cezar Lăzărescu made his debut in practice in 1949, with the projects realized within the IPC for the housing of non-family blocks and for the administrative pavilion of the Hunedoara factories (Ileana Lăzărescu, Georgeta Gabrea, Vise..., p. 28-30).

8 Like other architects who practiced in the interwar period, Octav Doicescu - the one identified by Mariana Celac as the source of inspiration for Călinescu's character - was one of those who got involved in the great socialist projects of the period, such as the constructions dedicated to the World Youth Festival, which took place in Bucharest in 1953. In parallel with these social-cultural construction projects, another major project of the political regime in the 1950s was the construction of the Danube-Black Sea Canal, taking up the theme of the great Soviet navigable canals. Along this canal, a network of riverside towns was to be developed, built according to urban compositions that were tributary to Socialist Realism. Cezar Lăzărescu was one of the authors of the projects for the cities of Cernavodă, Poarta Albă, and Năvodari in 1952 and Constanța in 1954 (Gustav Gusti, "The Danube-Black Sea Canal" in Arhitectura, no. 4-5, 1950, p. 133-140). In addition, Cezar Lăzărescu co-authored the detailed systematization plans and some of the buildings designed for the town of Medgidia between 1949-1953 (Gustav Gusti, "Housing in buildings with few masts", in Arhitectura, nr. 6-7, 1954, p. 25-26).

9 In parallel with his design work, Cezar Lăzărescu published a series of articles on city systematization and construction, starting in 1949. Naturally written in the language of the time, Lăzărescu's fairly extensive texts contain a large number of examples of the work carried out by the first design institutes ("From the practice of city planning", in Arhitectură și Urbanism, no. 12, 1952, pp. 16-25, "From the experience of designing and construction of housing quarters", in Arhitectura RPR, no. 1, 1953, pp. 3-12, "In connection with the design of workers' settlements", in Arhitectura RPR, no. 8, 1954, pp. 1-7). These, together with the materials published in the bulletins of the institutions involved in the systematization of cities, represent today, in the absence of (available) archival materials, a quite eloquent documentary material. Lăzărescu's work, Proiectarea și construcția orașelor (Bucharest, Ed. Tehnică, 1956) is - even if apparently a collection of data and rather technical notions - an illustration of the state of research at a certain moment in time and a detailed picture of the vision of the time on the principles of systematization.

10 Many of the large-scale articles in Arhitectura, the only architectural journal after 1948, were signed by the older Gustav Gusti or Horia Maicu.

11 According to the testimony of architect Constantin Jugurică, Cezar Lăzărescu became a close associate of the Dej family with the construction of the seaside resort. Cezar Lăzărescu is credited with the designs for the vacation villas in Snagov and Predeal built for the Dej family [Constantin Jugurică, "1965. Regele a murit (Gheorghiu Dej) - Trăiască Regele (Nicolae Ceaușescu)", in Ileana Lăzărescu, Georgeta Gabrea, Vise..., p. 179-180].

12 The first versions of the systematization sketch were published in Arhitectura in 1955, as a tribute to Socialist Realism, which generally produced low-rise housing developments on the outskirts of cities.

13 In 1961, Cezar Lăzărescu was awarded the State Prize of the Republic for his coastal systematization design and was decorated with the Order of Labor. The State Prizes were first offered in architecture in 1951, and the laureates at that time were Horia Maicu (45) and Nicolae Bădescu (38), followed in 1952 by Petre Antonescu (79), Duiliu Marcu (67) and Richard Bordenache (47). In 1953, the State Prize was awarded to Octav Doicescu (51) and P.E. Miclescu (52). The significance of awarding state prizes was to give credibility to the Socialist Realist architecture, associating it with outstanding personalities of the interwar period. From the same perspective, it can be said that the significance of the 1961 State Prize was to give credence to Modern Socialist Socialist architecture, that of a functionalist nature.

14 It seems that Elena Ceaușescu had asked Cezar Lăzărescu to design a villa with 'flourishes in stone and wood' (Constantin Jugurică, '1965 The King is Dead ...', p. 180). However, Cezar Lăzărescu's professional activity does not seem to have had a consistent interruption between 1961 and 1970: Guest House, Floreasca, Bucharest (1962), Governmental Guest House, Timișul de Jos (1964), Governmental Guest House, Bucharest (1964), Special Villa for Heads of State, Snagov (1965), Five Special Governmental Villas, Bucharest (1966)... Governmental Reception and Official Reception Hall at Snagov (1967)... Regional Palace in the Central Square of Pitești (1969). Also a controversy over a certain politically correct architectural expression made the facade of the Musical Theatre (Opera) and its author (Octav Doicescu) the object of severe criticism in Iosif Chișinevschi's speech at the Works for the Constitution of the Union of Architects (RPR) in Constructorul, December 27, 1952, p. 2. The facade was modified and the author was soon rehabilitated by receiving the State Prize a year later.

15 Constantin Jugurigă recalls an ideas competition held in 1970 for the construction of Otopeni Airport. Ascanio Damian, Horia Maicu and Cezar Lăzărescu took part in the competition, the latter's solution being the one preferred in the end (Constantin Jugurică, "1965 Regele a murit ...", p. 181). The rivalry between Maicu and Lăzărescu is also mentioned by Alexandru Panaitescu (Alexandru Panaitescu, De la Casa Scânteii la Casa Poporului. Patru decenii de arhitectură în București. 1945-1989, București, Ed. Simetria, 2011, p. 42).

16 In 1970, Cezar Lăzărescu was appointed professor, in 1971 rector, replacing Ascanio Damian, and in 1972 he was awarded the distinction of Emeritus University Professor (Alexandru Panaitescu, De la Casa Scânteii..., p. 77).

17 After 1971, the series of laws on urban planning and systematization proposed, first and foremost, a return to the traditional character of the street. According to Alexandru Panaitescu, the urban planning solutions based on this legislation were theoretically supported by Cezar Lăzărescu. He was also the one who coordinated the studies for the model groupings of residential blocks in future ensembles(ibidem).

18 The fragment is part of an interview with Contemporanul magazine, in the issue of August 3, 1984, entitled "New urban planning, expression of socialist civilization". Since 1966, Cezar Lăzărescu has written articles for the press: Scânteia, Contemporanul, Informația, Tribuna, etc.

19 Cezar Lăzărescu died on November 27, 1986, at the age of 63.