Oltenești Culele: the creative response of local communities to great historical events

Rosario Asunto opens her book on landscape with a chapter on the metaspatiality of landscape, referring chronologically to the definitions of landscape according to Italian explanatory dictionaries, which 150 years ago was described as a fragment of nature worthy of being a "subject of painting", a cutout, a frame extracted from a larger whole1. Whether that frame is the canvas, the window or the horizon, beyond that frame the landscape continues, in concrete terms, in one of two ways: with a uniform, repetitive landscape, as in the Sahara Desert, or with a varied landscape that changes significantly in appearance as the observer moves around.

Over the last half century, the concept of landscape has undergone an accelerated process of redefinition2, with man as a shaper of the natural landscape, user or 'cultural consumer', depending on his sensory and spiritual capacities, taking the human being at the heart of its meaning. Current value analysis in the field of built heritage seeks to explore the knowledge, skills and motives that led those who created what we today call built heritage to manifest themselves as they did through monumental art, architecture, ensembles or by relating buildings to the natural environment3. It also investigates to what extent the physical and cultural qualities of built heritage have been preserved and have or have not been "obstructed" by the interventions or constructions that have succeeded them, with a view to assessing the capacity of built heritage to transmit its value to humanity4.

Oltenia is a geographic space that has scenographic and strategic qualities on a vast scale, being a composition in crescendo from south to north, starting from the Danube, dominated by the hilly-platform area with a low general slope, followed by the Subcarpathians and ending with the mountain range. This space constitutes the visual base, or "blanket" on which the evolution of the architectural typologies of the Oltene cule architectural typologies is projected over at least three centuries. Rather, the landscape of the forested plateaus of the Getic Plateau 300 years ago is repetitive, uniform, sand dune-like, unique due to the elongated shapes of the hills and similar valleys in which the rivers functioned as ordering axes. Viewed from any of its high central points with long-distance visibility, this geographic space provides a similar visual setting.

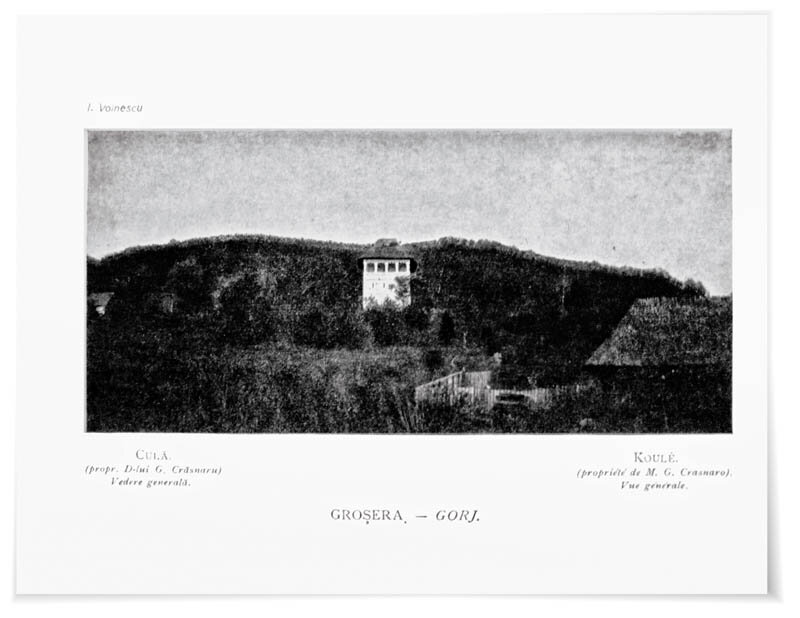

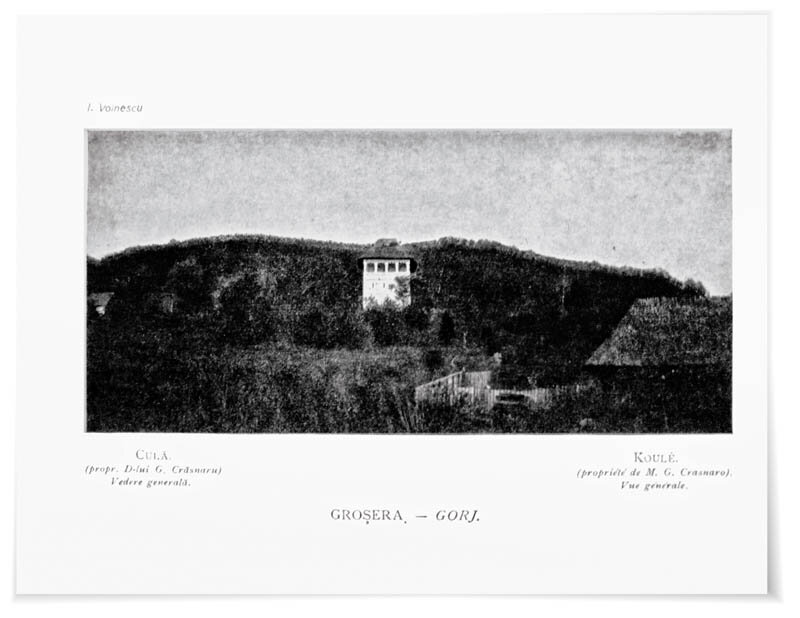

Always situated on high ground, up to 20 kilometers apart, with an urban typology specific to the manorial villages settled along the watercourses because of the agricultural land, most of the cula-type buildings dominated the settlements and the landscape, located on mounds in the center of the valleys or on hilltops with wide visibility.

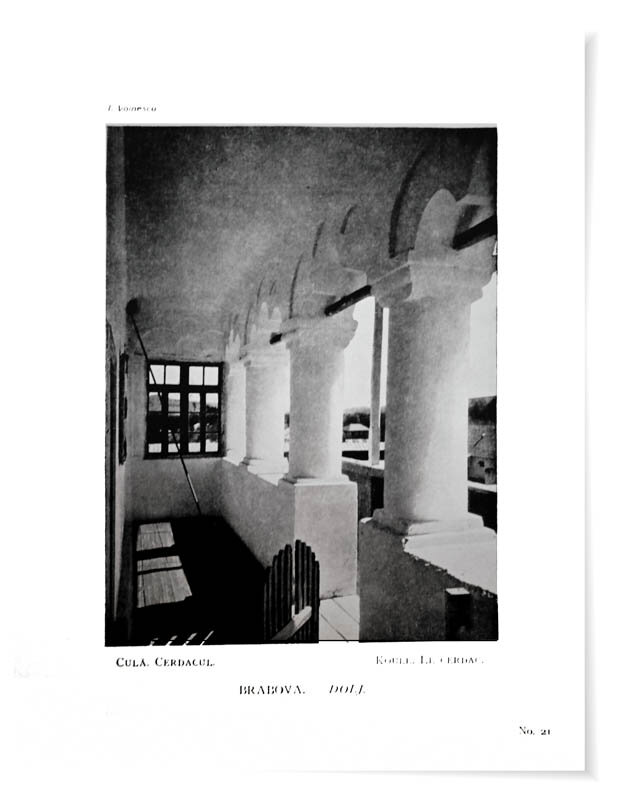

The dominant geometrical relationship of the unique cottage-type buildings to the village, the juxtaposition of material consistency with the precariousness of the peasant dwellings in terms of size, volumetric typologies, construction materials, insulation and uniqueness reassures their authority.

The 107 cottage-type constructions mentioned in the three monographs written by Iancu Atanasescu5 and Valeriu Grama, Radu and Sarmiza Crețeanu6 and Ion Godea7 are divided into 10 categories, the vast majority of which are tower-type constructions, the most independent form of composition.

The Austrian engineer Wilhelm Janeke claimed that the architectural program of the manor annexed to the manor house would be a reinterpretation of the donjon tower of the 12th8 and 13th centuries, when Teutonic knights9 were brought to Oltenia, probably due to the typology of the manor annexed to the manor house. An example of this could be the Trikule10 fortress at Svinița, in the area of the Danube Cazanelor, where, by order of King Béla IV in the 13th century, Johannite knights were brought and settled there, and later the fortress was also reinforced by Pippo Spano in the 15th century11. This fortress could be considered the first in the series and there may have been others of this type12.

The manors with secondary volumes sometimes containing defense chambers on the rear façade or volumes with a gazebo at the entrance, and the manors to which towers were added to or superimposed on the original volumes in the second half of the 18th century, were originally, in many cases, foundations of the noblemen of the time of Michael the Brave, of important rank. These manors, eleven in number, were arranged longitudinally in the Subcarpathian area at significant distances, with the exception of the Vlădaia manor.

The towers annexed to the manor were inhabited only during the attacks, the oldest ones being dated to the 17th century, located in the area of the Getic Plateau, but also in the Muntenia Plain, the farthest to the east was the Ciumernicu manor, in the present-day town of Popești-Leordeni, Ilfov, and another preserved manor of this type is the one in Frăsinet, Teleorman County. The newest construction of this type was the cula in Popești-Gorunești, founded by the Cârstea protopopul in 1805.

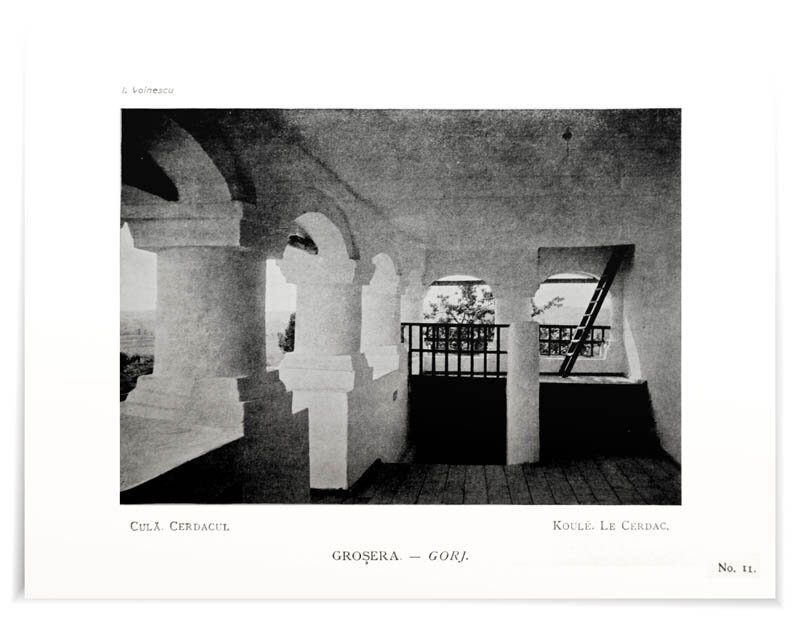

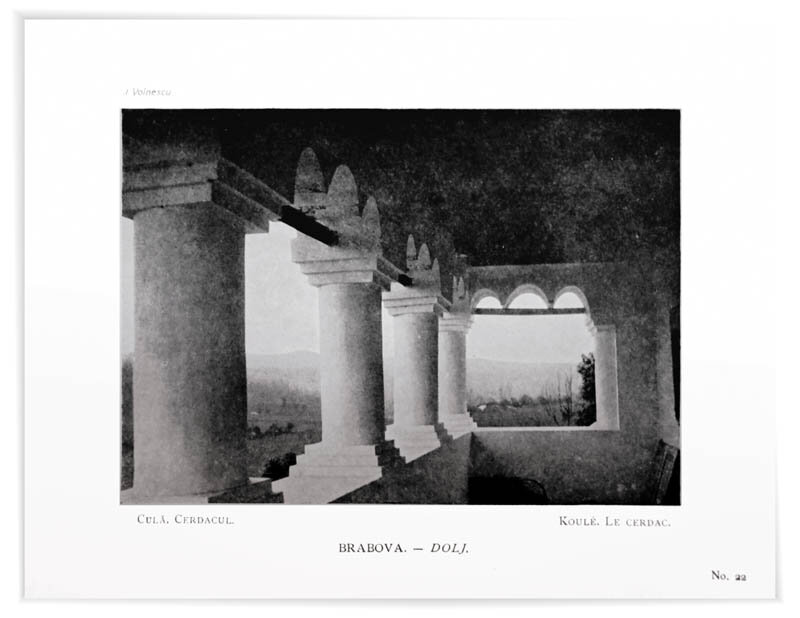

The fifth category representative of the second half of the 18th century is that of the towers of permanent dwelling, scattered on the hills of the Jiului Valley, gathering the most accomplished examples of the style: Curtișoara, representing the Classical Renaissance, Groșerea - exemplifying the Baroque, and the new cula of Măldărești - characteristic of Mannerism. They belonged to the boyar boyars who were the rulers of the Phanariot lords or administrators in the territory, and some of them settled in Oltenia after the Austrians withdrew.

Read the full text in issue 6/2013 of Arhitectura magazine

PHOTO:

SILVIA COSTIUC

Ion Voinescu

Monuments of peasant art in Romania, Bucharest, Carol Göbl,

Notes:

1 Rosario Asunto, Peisajul și estetica, Meridiane, Bucharest, 1986, vol. I, p. 47.

2 ICOMOS, World Heritage Cultural Landscapes, UNESCO-ICOMOS Documentation Center, 2009, p. 7.

3 Five (II-VI) of the six cultural criteria imposed by UNESCO for inscription on the World Heritage List refer explicitly to the cultural values that a monument, ensemble or site can convey through its preserved physical characteristics. Cf. UNESCO, Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention, World Heritage Center, 2013, pp. 49-53 and pp. 77-98.

4 UNESCO requires the requirements of authenticity and integrity to be met in relation to the cultural criteria for the inscription of listed sites. Cf. UNESCO, Ibidem, p. 79-95.

5 Iancu Atanasescu and Valeriu Grama, Culele din Oltenia, Craiova, Editura Scrisul Românesc, 1974.

6 Radu and Sarmiza Crețeanu, Culele din România, Bucharest, Meridiane Publishing House, 1969.

7 Ion Godea, Culele dinRomânia - tezaur de arhitectură europeană, Timișoara, Editura de Vest, 2006.

8 In 1150, when Oltenia was occupied by King Géza II, Franconian settlers from Germany were called in, then, in 1211, Teutonic knights were called in to fight against the Pechenegs and Cumans. Cf. Wilhelm Janeke, op. cit., p. 37.

9 After the Mongol invasion of 1247, Oltenia came under the vassalage of King Béla IV, who brought several dozen Teutonic knights into the territory with the intention of colonizing the area and building fortresses, these knights being forbidden to receive settlers from Transylvania. Cf. Neagu Djuvara, O scurtă istorie a românilor povestită celor tineri, Bucharest, Humanitas Publishing House, 2002, p. 44.

10 Another place-name etymologically related and geographically close to Șvinița is Ada-Kaleh, an island-city, strategically located, like Șvinița. It has been inhabited since antiquity and was fortified in the 13th century, but also on the threshold of the 17th century by the Austrians.

11 Ilie Sălceanu and Nicolaie Curici, The "Șvinița" Phenomenon, Satu Mare, Solstițiu Publishing House, 2012, p. 259.

12 By their location on the left bank of the Danube, at equivalent intervals between Cazane and the mouth of the River Ji, some of them also built on ancient ruins: Desa, Cetate.