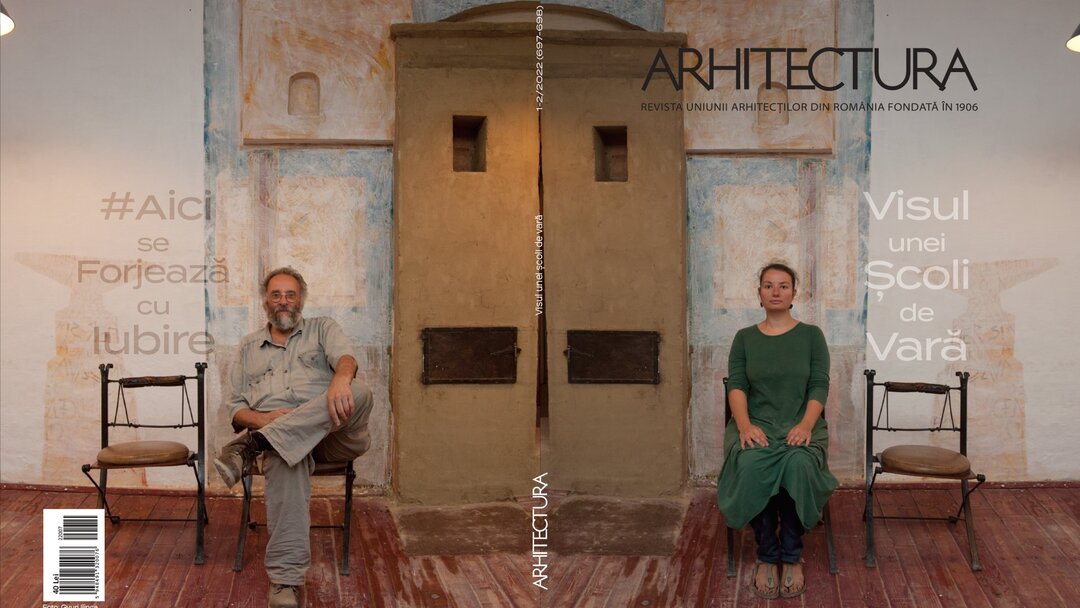

The beginning or why is Alexandra beating iron at the manor?

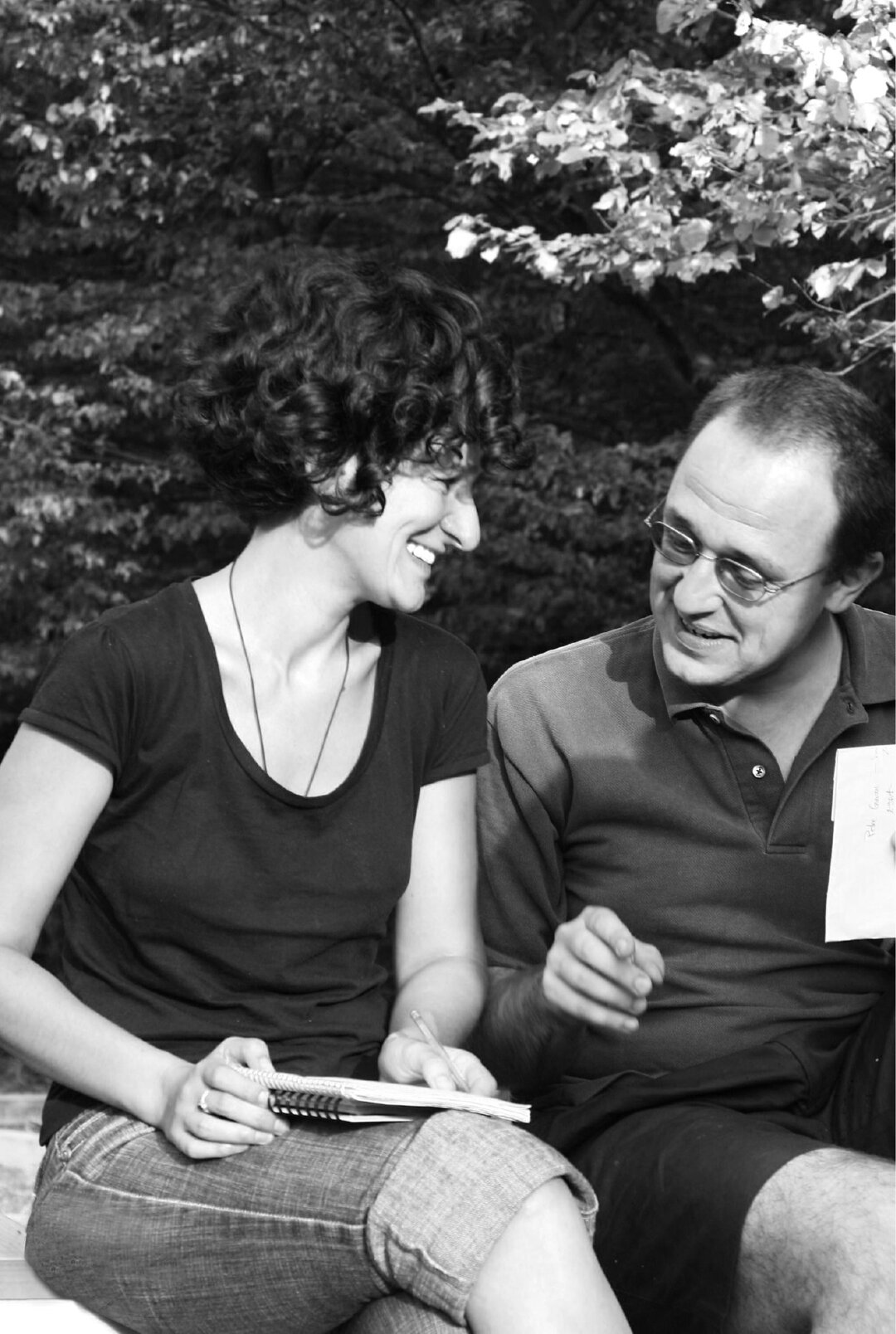

©Mihai Bodea-Tatulea

Of all the stories I can tell you, let me begin with mine. There was a proud horse that often passed through the lane of the village where I grew up, galloping alone, missing his rider or his cart. He seemed a presence from another world. It was some time before I identified whose it was and what of it. And then I watched, first furtively, then begging to assist, as he mounted. The colt and the horse knew each other, or so it seemed. There was a matter of language there, very perceptible. Then, from hiding, I saw for the first time how metal becomes fire. When the same man repaired the skeleton of my sleigh and taught me to hammer a nail, it seemed to me a very beautiful and useful craft. I made and played with families of nails, each with its own personality. The carts, with their many shapes and loads, as many as I could catch, in a remnant of an already partially perverted village, would also go from time to time to the same man's yard. If the world had been made of metal, I would have made the catch that he could fix it; and he did so as long as the world needed him.

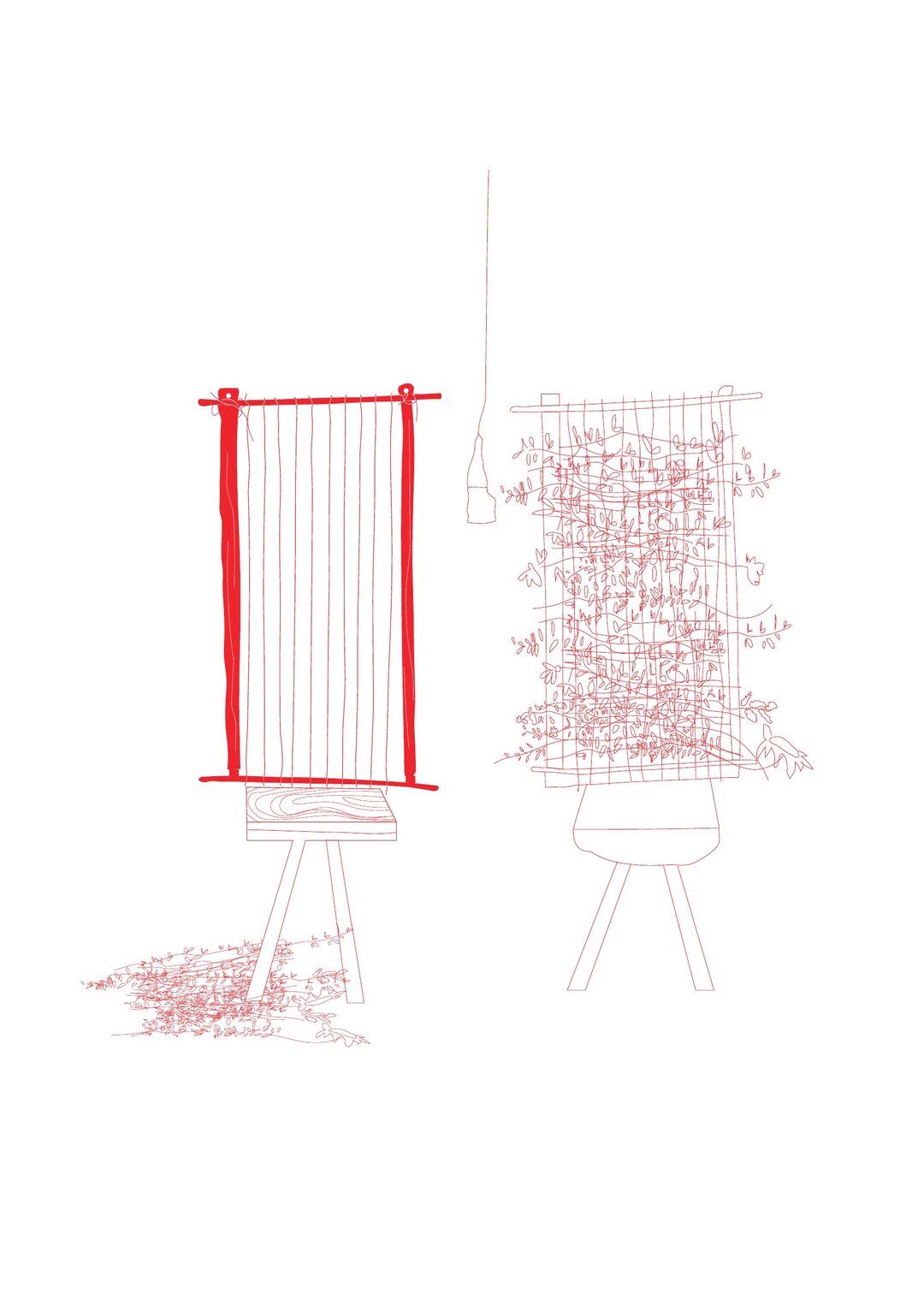

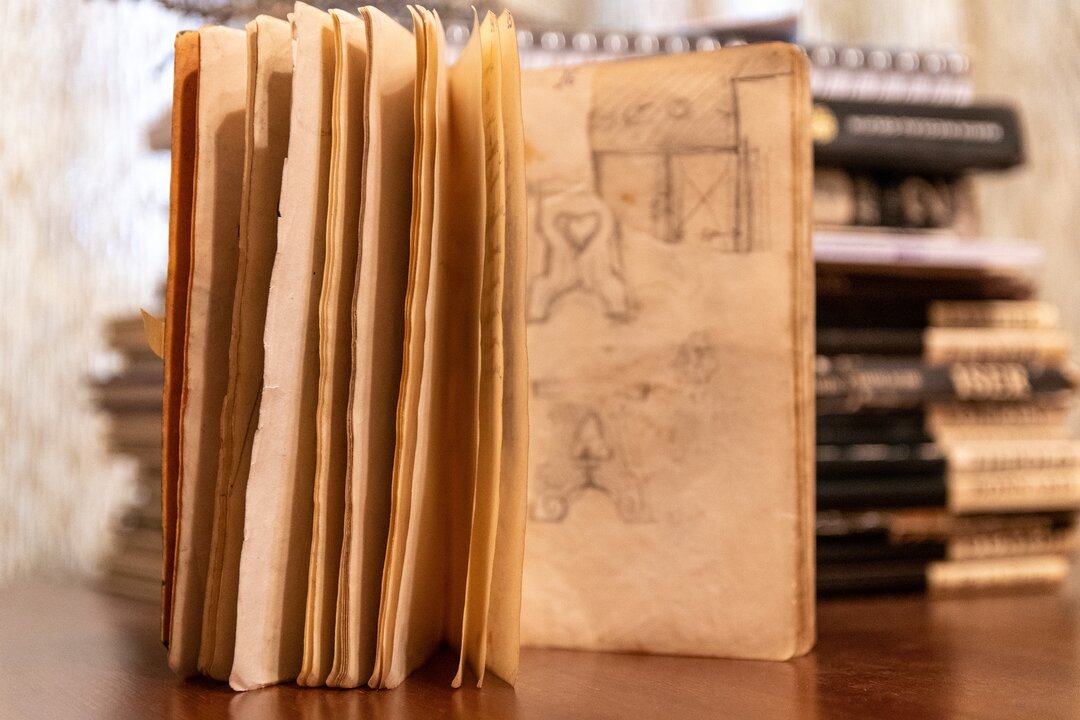

And over all this the years have rolled on. A few years ago, my memories met the reality of a forge, in a village called Țibănești, where I went to a festival of blacksmiths, French and Moldavian, to understand something of the world of the craft. I was preoccupied by several questions, including "how is drawing embodied?", "what is the relationship between architecture and the maker, whatever its nature?", "how do you decide which is the best line when you are building a form?". Here, the first exercise was making a nail. My days began and ended at the forge. I remember that fire in the forge, which changed the temperature far beyond the already unbearable outside. I was working on the construction of the village bus station. The loud sound of hammers, the bustle of work on three anvils, the metal splinters bouncing, the long, large-section bars with reddened ends, the ceremonial cracking of coals, the mixture of sweat and slag, a clearly sensory world in which it was out of date to take out a laptop to draw objects. It had to be different. At the end of a marathon in which you participate fully in the realization of an idea, you have a kind of clarity. My design ideas in part melted, and the rest underwent processes of bending, warping, twisting. I don't know what replaced them, but the experience was revealing. Once you've "put your hand" on the reddened iron, you carry with you a deep mark.

Since then, Țibănești has been the incubator and experimental territory of thoughts that test objects and question the ways and systems of generating forms, of simplifying processes, of understanding the reasons and life of the material, of making architecture come alive.

The object, proud, noble, almost eternal, by the very nature of the material, is sometimes placed in front of us without understanding where it comes from and what is its previous life. The backstage of the object has questions, anxieties, limitations, dust, toiled bodies, a sense of modesty in the face of the unknown (as if you never know enough). But you also have a consistent pleasure in being part of the birth of something whose existence depends on you. Something that you are constantly questioning and shaping. Something that you dream and pursue to a point where you let it happen. Your being sometimes focuses on an object.

When you work on a construction site like the one in Țibănești, it exerts such a powerful attraction that you have a sense of a center, which keeps deepening through the things that revolve around it, the ideas that emerge, the remarkable encounters with very different people who are working side by side with you on this problematic hull of craftsmanship and architecture in the contemporary world.

After the blacksmiths of Țibănești left more of a memory, we have tried to reconstruct a present-day peripeteia and to bring the village and the town, the blacksmith and the architect, the Romanian and the Frenchman, into communication, in a weaving from which we have extracted the things that enrich each other, rather than those that divide them.

From the African blacksmith in Medina to the people who pulsate at the sight of metal, running in the middle of the night after pieces of popular ironwork, to the architects who try out old formulas of finishes in iron objects of today, I have convinced myself that the attraction given by the world of blacksmiths still exists, even if discreet, hidden, taking other forms and taking more interest in the city.

I would like this project to help to reconsider an attitude - both of the blacksmith towards himself and of others towards him - it is a great art to know how to make something with your own hands; blacksmithing is an old-fashioned craft only insofar as there is no imagination to respond to a social context through it. That is why I have tried to recover some fragments of history scattered around the world, to recall the past and the present of this craft and perhaps to spark something.

Ioana: But why have things that seem very simple, like putting reeds on a house or making a nail, become so important? And why are they so important for the city-dweller, why do they mark him?

Alexandra: These things just seem so simple, in essence they are very profound. They are simple only in form, but not in content. Take, for example, the repetitive activities of low complexity: sifting sand, crumbling clay, mixing cellulose and so on. In all of them you're making repetitive gestures that give you the opportunity to be with yourself for quite a long time. And you're not used to that, you come from another time, another life. You practice patience.

Then you re-circulate the mind-hand-eye connection, it's something that's something that's built up after so much contact with a screen. To make a correct nail, with a good section, with a centered and beautifully shaped head is not an easy thing, it's an exercise that requires many "strings".

You have a discovery about yourself in contact with matter. You understand better who you are.

Ioana: Do summer schools have something of Don Quixote battling the windmills?

Alexandra: Yes. They do. This apparent weakness is our strength. Because it allows us to do what you can't do in a university or other places. To knead some almost impossible ideas, to think "what if" and to execute, to assume the waste of resources for the sake of knowledge.

Our goal is the enriched participant.

And since you mentioned Don Quixote having a vibration, I would say that all summer schools are about vibration, they are about a life that is alive, because architects tend to freeze things; they get into processes, into optimizations, into over-thinking, into correlating many layers of information vital to the development of a place.

This novel also speaks of a certain lightness, you don't take yourself so "seriously". And then you have a different approach to mistakes. Our education, our society, has instilled a fear of mistakes.

In summer schools people learn to make mistakes and they learn to analyze, talk about it and move on. We try to integrate these pranks into a transmission ecosystem, they are very useful for me in guided tours.

Moreover, the generosity of Șerban Sturdza to invest a lot of energy in including these learning exercises in the site, builds out of these insecure learners, step by step, more courageous people.

Ioana: And eventually like the mansion of Țibănești and the whole ensemble, which nobody is in a hurry to finish. The point is that the architect and the client want to finish a project as quickly as possible, there is always pressure. You seem to have infinite time.

Alexandra: In Țibănești we tried a post 2004 "slow food" genesis translated into slow architecture/reutilization/conversion. Why? Because it sets things well in the community and because it's only after 10 years that you start to draw your first conclusions, to exist, that's what anthropological studies say. All the actions here have a punctual relevance, but also an overall relevance or network that can be highlighted over time.

The project aims to regenerate the manor house and its annexes for the benefit of the community, and therefore also to involve the community in developing its own cultural agenda and making use of the manor house. So we need to know and trust each other, and this is built over time.

Because the birth is long, we think about how to bring the building to life before it's finished, so in pieces, and then at each stage of its growth and healing, we use the spaces as creatively as we can. Here the place gradually reveals itself, and in fact your interest is in realizing what is valuable by itself in that place and what its guiding axis is.

Moreover, for us, it is much more nourishing to approach a project in this way, in contrast to the mechanisms developed by, say, a European-funded project, where the learning component is limited to the design and implementation team. The Carp Mansion has so far been home to more than 4000 people, its purpose is to be a school and incubator for new generations of built environment specialists. Its role is to give courage to others to embark on such an adventure. As Vintilă Mihăilescu said: "I wish this mansion would never end".

Then, if you ask me again why "slow arhitecture", I'll tell you this: because the world is fast food and it's clear that you have a lot to learn from such a contrast. Simply living slower is a learning experience. While we are rushing, Europe has started to slow down, to see the positive values of slow living.

Ioana: Could you see such a summer school in the middle of Bucharest?

Alexandra: Ha! I wondered that myself. I've had a couple of attempts to do summer schools in Bucharest, all kinds, for example, in the staircase of the block, a relevant play space for the city.

In summer schools you're in a kind of island, where people are also kept by the "fortress walls", they have nowhere to go and nothing to do. Whereas in Bucharest you have to know how to attract and keep them, it's very difficult.

It seems to me that you need other tools here. At one point I wanted to do a city laboratory. A dozaj with design & build workshops, music concerts, themed evenings, activation of unused space. Tables played an important role, we were thinking of closing streets, opening dead ends, turning cooking into performance, and seating - an occasion for design and architecture. The simplest, but not meaningless, universal event, a primary and spiritual gesture at the same time, dinner, was staged with design and architecture to demonstrate the ability of form to change moods, perceptions, atmospheres and perhaps even life paths.

Each dinner was a thematic encounter, about happy cities, about how art and design can be relevant to the everyday lives of a diverse audience.

I think everyone has their own archive of ideas. It's a good place to grow.

Ioana: How do you train students in your blacksmithing classes?

Alexandra: There are two parts to the training of future ironworkers, theoretical and practical. In addition, we try as much as possible to transfer knowledge from the arts and life to them.

The training of the students involves going through a number of study modules covering: Tools, Protective Parts, Volutes and Decoration, Fasteners, Supporting, Rotating and Closing Parts, Handrails and Straight Handrails.

At the same time, the blacksmith's workshop is working on the creation of confections that are inserted in restoration sites or contemporary architectural works. A new direction is the creation of introductory modules in the art of blacksmithing for all those interested in discovering cultural heritage.

Today, the prestigious association of craftsmen "Les Compagnons du Devoir et du Tour de France", a French non-profit organization, aims to offer the opportunity for everyone to fulfil themselves in and through their craft. Today, the journey around France, a practice for the companions to perfect their skills, has become a journey around Europe, and the village of Țibănești has become a living point for the transmission of the craft of blacksmithing, recognized at European level.

Our project's name revolves around the traveling horses - art blacksmiths, who have come to the "Iron at the manor house!": Clement Côme, Sylvain Gabriel, Fabien Monestier, Fabien Monestier, Victor Hornez, Antoine Deroo, Pierre Hosta, Sébastien Palomas, Léo Coutant, Gabriel Padioleau, Gaëtan le Gall, Sebastien Bridonneau, Brendan Olivier, Quentin Guillerm, Germain Fortin, Adrien Corbin. Through their travels, they all seek a threefold formation: professional, cultural and human.

It is interesting to note that UNESCO has inscribed companionship, this network of transmission of knowledge and human identity through crafts, on the list of Intangible Cultural Heritage. In the context of globalization, the protective measures of Intangible Cultural Heritage are an important factor in maintaining cultural identity.

At present, We're striking iron at the manor! powered by Maria Association in partnership with Pro Patrimonio Foundation is trying to introduce a system of companionship in Romania, adapted to the needs and national cultural specificities.

Ioana: What is it like working with Șerban Sturdza?

Alexandra: The closest image is Matrioska dolls, there's always something to discover.

Ioana: Were you looking for a master? A model?

Alexandra: Yes, it seems to me that there's a shortage of role models in our society and it seemed to me that architecture is so complex that you need a guide to lead you through the labyrinth once.

I first listened to Șerban Sturdza talking about windows into the history of culture and civilization and I empathized deeply. I knew he was the right guide. It's a natural relationship, a lot of people today are embarrassed by this kind of mentoring, I look at churches and I see that churches have been built on the foundations of older ones and so on. There is nothing shameful here, it can even be a shortcut and a reinforcement of values, if they are well dosed and if the relationship is healthy. Vintilă Mihăilescu said "looking back to the future".

Ioana: What's next?

Alexandra: We dream of other blacksmiths to prove their usefulness in the villages; we dream of the Carp Cultural Hub, the first craft school in Moldova, to finish the space and put it into use, we dream of the first European diplomas in the art of ironwork.

We dream of products created in blacksmithing that will be loved in our homes and that will be able to support a few blacksmiths from Țibănești trained in our project. We dream of understanding the need to train young people in this craft, to see them proud of the fruits of their labor and not embarrassed for practicing a seemingly old-fashioned trade. Our dream is to create a living space where, in addition to seasons and summer camps, we have a community involved in local activities and workshops, actively enjoying the places we create and developing their own vision, their own program.

We dream of our lab being populated and in demand by beautiful people with ideas and zest.

We dream of a natural proximity to a living heritage.

© Alexandra Culescu

%2035.pdf--16926-m.jpg)

--16931-m.jpg)