Se întâmplă fără noi

It’s happening without us

| Aveam intenția să scriu un „contre-point” - privind „forma urbană” - la „Bigness”, eseul apărut în ultimul număr al revistei Arhitectura. Reluând note din anii ’80 și comparându-le cu publicații recente, mi-am dat seama de enormele schimbări petrecute în ultimele decenii la nivel planetar și urmările lor pe planul teritoriului, al urbanismului și al arhitecturii. Prima opțiune mi s-a părut aproape ridicolă în fața tsunamiului urban. |

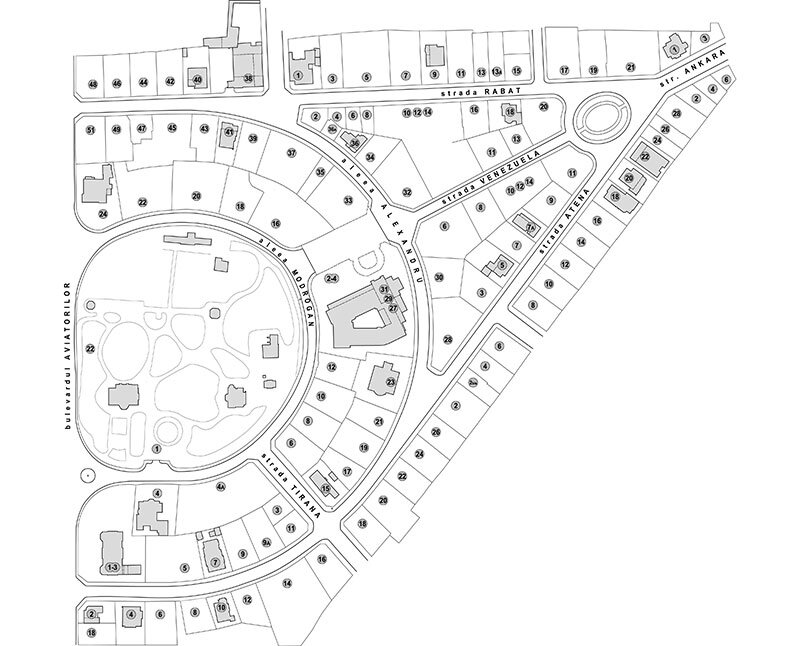

| Un termen - aparent puțin nociv - „l’étalement de la ville”1 poate rezuma, într-un fel, această situație. Este vorba de o extindere a urbanului - în forma sa de „periferie” - la ansamblul teritoriului.

Regiuni întregi, din America de Nord, Europa, Asia de Sud-Est, sunt atinse de acest „mitage du territoire” (ciuruire a teritoriului întocmai cu o țesătură devorată de molii - n.r.). Creșterea populației, ameliorarea condițiilor social-econo-mice, rentabilitatea investițiilor, dar mai ales perenitatea visului întoarcerii la natură și al posedării unei case2, iată, simplificate, câteva din motivațiile acestui exod. „Motorul” noii libertăți este automobilul. Implicațiile sunt pletorice, unele copleșitoare. Un singur exemplu: „Franța oferă o ilustrare comprehensibilă pentru modalitatea de amplasare a rețelelor în teritoriu. În succesiunea celor trei factori determinanți - infrastructurile, zonele de comerț și birouri, etalarea rezidențială - trebuie să începem cu drumurile și cu automobilul”3. Rămânând în domeniul unor preocupări mai apropiate, iată cum prezintă David Mangin situația: „În Europa de astăzi, împărțirea ideologică și profesională a activității de urbanizare a devenit radicală: infrastructurile (rețelele de drumuri în primul rând - n.a.) pentru ingineri; produsele, tipologiile și terenurile pentru promotori; fațadele pentru arhitecți”4 și, mai departe: „în 70% din cazuri, topografii, departe de a face numai măsurători, sunt veritabili «maîtres d’œuvre» ai lotizărilor. Ei exercită un autentic rol de urbaniști pentru care formarea profesională nu i-a pregătit în vreun fel”5. Este frapantă absența unei viziuni de ansamblu, fragmen-tarea extremă a intervențiilor, aleatoriul competențelor, obsesia rentabilității pecuniare. Dar să privim lucrurile mai atent. Vom observa repede că aceia care au deschis această „Cutie a Pandorei” au fost arhitecții înșiși. La sfârșitul anilor ’50, când Peter Smithson refuză ideea (Choisy și Le Corbusier) „spațiului urban” grec antic, el o făcea și pentru a da mai multă pregnanță interesului pe care îl manifesta în acea perioadă pentru „limbajul” urbanismului american bazat pe distanță (distancing) ca instrument de a pune în raport clădirile6. El va fi, de altfel, la originea interpretării planului-masă pentru IIT (Mies van der Rohe) ca o grilă uniformă, anticompozițională. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 4/2012 al revistei Arhitectura |

| NOTE1.

David Mangin - LA VILLE FRANCISéE, Editions de la Villette, Paris, 2004 (p. 11) Studiul este remarcabil în partea analitică și o parte dintre concluzii. Soluțiile - limitate, par impregnate de un anume „politically correct”.

2. Patrick Leuleu - „La maison est toujours le rêve des français” în LE FIGARO din 10 iulie 2012: „80% des français rêvent d’avoir une maison individuelle” (p. 15). 3. „....la France offre une bonne illustration pour tenter de comprendre précisément la façon dont se mettent en place les réseaux sur des territoires. Dans la chronologie des trois facteurs déterminants - les infrastructures, l’urbanisme de commerces et d’entreprises, l’étalement résidentiel - c’est par la route et l’automobile qu’il faut commencer (D. Mangin - ibidem 1, p. 75). 4. „Dans l’Europe d’aujourd’hui, la division idéologique et professionnelle du travail urbain est devenue radicale: les infrastructures aux ingénieurs; les produits, les typologies et les terrains aux promoteurs; les délaissés de la voirie aux paysagistes, les façades aux architectes” (D. Mangin - ibidem 1, p. 75). 5. „Dans 70% des cas, les géomètres, loin d’être seulement des arpenteurs, sont les véritables «maîtres d’œuvres» des plans de lotissement. Ils exercent un vrai rôle d’aménageurs auquel leur formations ne les a pas forcément préparés...” (D. Mangin - ibidem 1, p. 170). 6. Peter Smithson - SPACE AND GREEK ARCHITECTURE (în The Listener, 16 octombrie 1958), citat de Jacques Lucan în COMPOSITION, NON COMPOSITION, Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, Lausanne 2009, p. 451. |

| I was intending to write a “contre-point” to “Bigness” (the essay I published in the last issue of Arhitectura), on the subject of “urban form”. Going back to my notes from the 1980s and comparing them with recent publications, I realised how enormous have been the changes that have taken place globally in the last few decades and their impact on the ground, at the level of urbanism and architecture. My initial choice seemed to me almost ridiculous when confronted with the urban tsunami. |

| The seemingly innocuous term “l’étalement de la ville”1might, in a way, sum up this situation. It is a question of the extension of the urban - in its “peripheral” form - to the territory as a whole.Entire regions of North America, Europe, and South-East Asia are affected by this “mitage du territoire” (the eating away of a territory, like a fabric being devoured by moths).

Population growth, improvements in socio-economic conditions, the profitability of investments, and above all the perennial dream of going back to nature and owning a house 2 - in simple terms, these are just a few of the reasons for the exodus. The engine of the new freedom is the motorcar. The implications are plethoric; some are overwhelming. Here is just one example: “France provides a good illustration when it comes to understanding exactly how territorial networks are put in place. If we are to take the three determining factors in turn - infrastructures, office and shopping areas, residential sprawl - then we have to begin with roads and motorcars.” 3 Still in the area of similar concerns, David Mangin presents the situation as follows: “In today’s Europe, the ideological and professional division of labour in urbanism has become radical: the infrastructure (primarily roads - my note) goes to the engineers; the products, typologies and terrains go to the developers; the public highway verges go to the landscape gardeners; the façades go to the architects”4 and “in seventy per cent of cases, the surveyors, far from being merely surveyors, are true ‘master builders’ of subdivision plans”.5 What is striking is the lack of an overall vision, the extreme fragmentation of the work carried out, the randomness of the competencies, the obsession with pecuniary profitability. Let us look at things more closely. We shall quickly notice that the people who opened this Pandora’s box were the architects themselves. In the late 1950s, when Peter Smithson rejected (Choisy and Le Corbusier’s) idea of the ancient Greek “urban space”, he did so in order to lend greater weight to the interest he was showing in the “language” of American urbanism at that time, an urbanism based on distancing as a tool for making buildings relate to one another.6 It was Smithson who originated the interpretation of plane/mass for IIT (Mies van der Rohe) as a uniform, anti-compositional grid. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| NOTES:

1. David Mangin, La ville francisée, Editions de la Villette, Paris, 2004 (p. 11) The study is remarkable for its analytical section and a part of its conclusions. The limited solutions seem imbued by a certain “political correctness,” however. 2. Patrick Leuleu, “La maison est toujours le rêve des français,” Le Figaro, 10 July 2012: “80% des français rêvent d’avoir une maison individuelle” (p. 15). 3. “[L]a France offre une bonne illustration pour tenter de comprendre précisément la façon dont se mettent en place les réseaux sur des territoires. Dans la chronologie des trois facteurs déterminants - les infrastructures, l’urbanisme de commerces et d’entreprises, l’étalement résidentiel - c’est par la route et l’automobile qu’il faut commencer (D. Mangin, ibid, p. 75). 4. “Dans l’Europe d’aujourd’hui, la division idéologique et professionnelle du travail urbain est devenue radicale: les infrastructures aux ingénieurs; les produits, les typologies et les terrains aux promoteurs; les délaissés de la voirie aux paysagistes, les façades aux architectes” (D. Mangin, ibid, p. 75). 5. “Dans 70% des cas, les géomètres, loin d’être seulement des arpenteurs, sont les véritables «maîtres d’œuvres» des plans de lotissement. Ils exercent un vrai rôle d’aménageurs auquel leur formations ne les a pas forcément préparés...” (D. Mangin, ibid, p. 170). 6. Peter Smithson, “Space and Greek Architecture”, The Listener, 16 October 1958, quoted by Jacques Lucan, Composition, non-composition, Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, Lausanne 2009, p. 451. |