Formă, imagine, imagerie și dragoste pentru geometrie

Form, image, imagery, and love of geometry

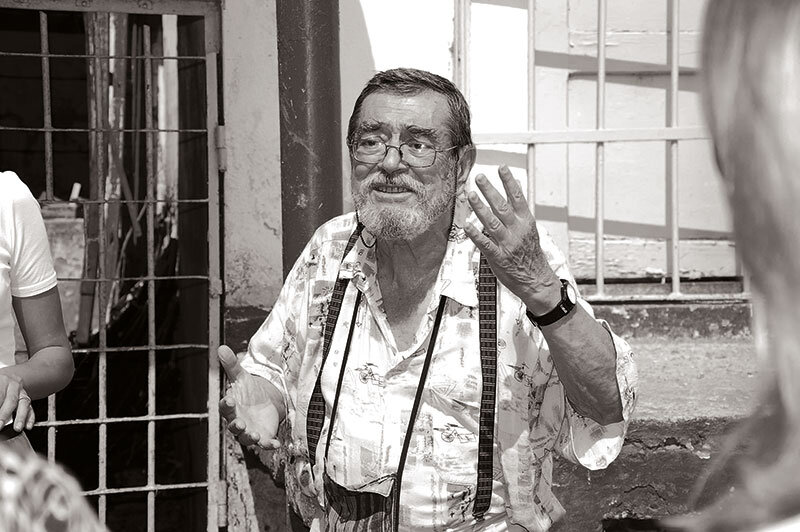

| În principiu, dacă simțim că ne aflăm în prezența unei opere de artă, atunci aceea chiar este o operă de artă. Așa cred eu. Ea ni se prezintă mai întâi ca formă. Unii arhitecți, mai ne-latini, nu reușesc să se împace complet cu latura vizuală a lucrurilor. Nici eu încă nu pot, nici moral, nici sentimental. Dar nici nu putem să ne împotrivim importanței formei, când ne referim la artele vizuale. |

| În primul rând, pentru că ceea ce ne mișcă mai întâi în prezența unui obiect suspectat de a fi artă e forma, adică o anumită alchimie a liniilor, culorilor, luminii, spațiului, suprafețelor. Dar, asociat acestei aparențe, mai există ceva care stârnește reacția estetică, o calitate comună pe care trebuie că o au un vas etrusc, un tablou de Gaugain, o carpetă din Anatolia, vitraliile din Chartres, o sculptură olmecă, frescele lui Fra Angelico și capela din Ronchamp. Este intuiția că în spatele vizualului se află o poveste, spusă pentru cine are urechi de auzit, dar care mai întâi are nevoie de o anumită forță pentru a pătrunde dincolo de stratul superficial al formei. Și dacă aceea e o operă de artă, găsește acolo o confirmare.

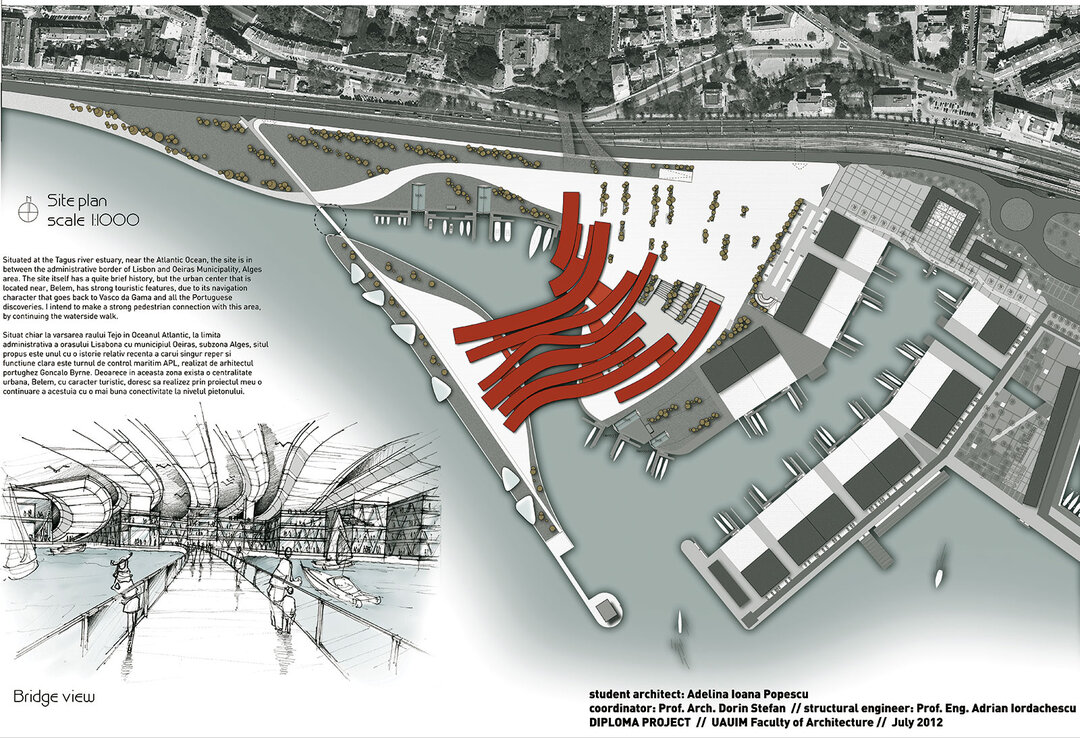

Ne plângem, azi, de prevalența imaginii asu-pra valorii. Ne temem, se vede, pentru nimbul de noblețe al artei, dat de semnificații. Deci nu ne temem atât de mult de prevalența formei asupra valorii seman-tice, cât ne temem de prevalența imaginilor despre forme și valori. Imaginea unei valori se cheamă prestigiu, iar imaginea unei forme se cheamă reprezentare. Ne temem de false prestigii și reprezentări autosuficien-te, create de profesioniștii imagisticii - sociologi sau fotografi. Nu ne temem pentru noi, ci ne temem pentru studenții noștri, bucuroși să cadă în capcanele imaginilor puternice. Reprezentările de arhitectură sunt pentru studenții noștri precum Lorelei, iar ei vâslesc prin publicații fără să mai vadă - ascuns pentru ei în adâncuri - textul. Adică sensul. De fapt, pentru că profesioniștii se străduiesc să-și facă imaginile atât de retinale, pentru întregul public vizualitatea e adesea suficientă, în loc de experiență estetică. De asta ne temem. Nu ne temem de deformările pe care subiectivismul nostru le produce la contactul cu forma artistică, pentru că savanții ni l-au legitimat, iar noi credem că-l controlăm. Cât de cât. Restul, pe care îl numim subiectivitate, îl acceptăm aproape cu mândrie. Ne asumăm derogările pe care și le permite percepția noastră vizuală, niciodată sută la sută doar vizuală, ci contaminată prin filtrul pânzei inefabile care e imaginarul propriu. Savanții s-au încumetat să investigheze inevitabilul grad de opacitate al formei la întâlnirea cu vizualul. Rudolf Arnheim, de exemplu, a analizat interacțiunea dinamică a forțelor vizuale și influența lor asupra percepției. Contează și nivelul de intelectualizare a operei, care merge de la un produs cultural asimilat până la obiectul avangardist, sfidător față de principiile consacrate ale compoziției. Percepția depinde și de ipostaza conjuncturală a subiecților, care permite sau nu instalarea stării de orientare favorabilă receptării estetice. Admițând că starea de receptivitate există, fie sub formă de contemplare facultativă, fie ca studiu metodic, plăcerea se întrepătrunde moment de moment cu cunoașterea. Astfel, competența privitorului este cea care, în final, decide asupra nivelului de experiență estetică. Și totuși, indiferent dacă receptarea se află mai departe sau mai aproape de receptarea com-pletă, democrația a decis să admită o mare toleran-ță față de toți receptorii artelor, pentru că diversita-tea experiențelor estetice, chiar sub aspectul calității, nu produce niciun rău. Problema apare atunci când receptarea estetică nici nu mai are loc, ea oprindu-se la stadiul de percepție vizuală. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 4/2012 al revistei Arhitectura |

| In principle, if we feel that we are in the presence of a work of art, then that thing really is a work of art. That’s what I think. First of all it presents itself to us as a form. Some non-Latin architects can’t really get along with the visual side of things. Nor am I able to yet, either morally or sentimentally. But that doesn’t mean we can go against the importance of form when we talk about the visual arts. |

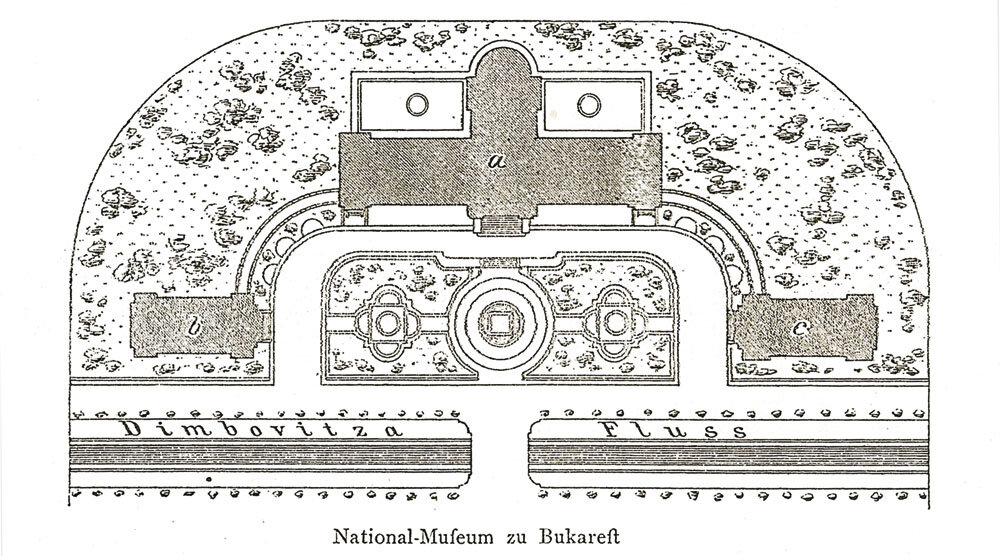

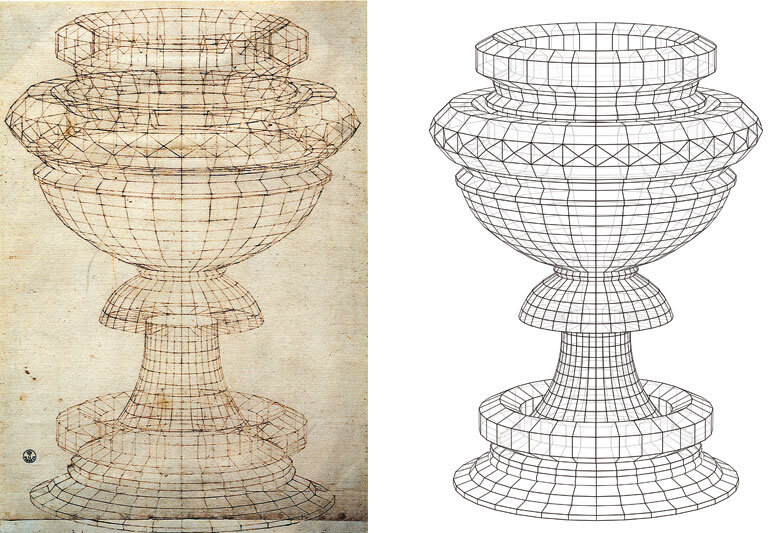

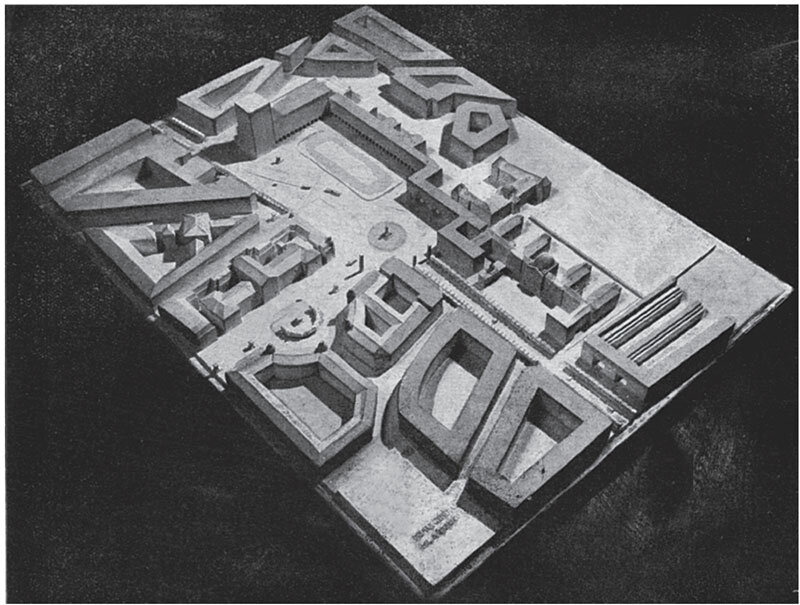

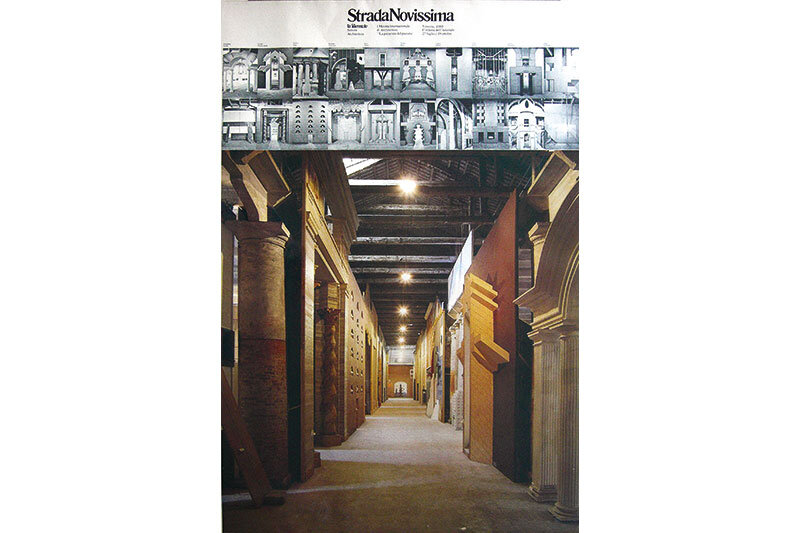

| In the first place, this is because what moves us when we’re in the presence of an object suspected of being art is its form, i.e. a certain alchemy of lines, colours, light, space, surfaces. But combined with this appearance there is also something that evokes an aesthetic reaction, a shared quality possessed by an Etruscan vase, a Gauguin painting, an Anatolian rug, Chartres stained glass windows, an Olmec statue, Fra Angelico frescoes, and the Ronchamp Chapel. It is the intuition that behind the visual there is a story told for those that have ears to hear, but which first of all requires the strength to pierce through the superficial layer of form. And if it is a work of art, it will find its confirmation there. Nowadays we complain about the prevalence of image over value. It’s apparent that we fear for the nimbus of nobility that meaningfulness lends art. We are not so much afraid of the prevalence of form over semantic value as much as we are afraid of the prevalence of images over forms and values. The image of a value is named prestige; the image of a form is named representation. We are afraid of fake prestige and self-sufficient representation, created by image professionals: sociologists and photographers. We’re not afraid for our own sake, but for the sake of our students, who so blithely succumb to the snares of powerful images. To our students, architectural representations are like the Loreley, and they row through publications without seeing the text, hidden from them in the depths. Which is to say, without seeing the meaning.

In fact, because the professionals strive to make their images so retinal, the visual rather than aesthetic experience is often sufficient for the public as a whole. We’re not afraid of the distortions that our subjectivism produces on contact with artistic form, because the scholars have legitimised it for us, and we think that we control it - to a certain degree. As for the rest - what we call subjectivity - we accept it almost with pride. We accept the derogations permitted by our visual perception, which is never one hundred per cent visual, but contaminated through the filter of the ineffable gauze that is our own imagination. The scholars have ventured to investigate the inevitable degree of opacity of form in the encounter with the visual. Rudolf Arnheim, for example, has analysed the dynamic interaction of visual forces and their influence on perception. What also counts is the level of intellectualisation in a work, which ranges from assimilated cultural product to avant-garde object, defiant towards the established principles of composition. Perception also depends on the circumstantial hypostasis of the subject, which may or may not allow a state of orientation favourable to aesthetic reception. If we allow that the state of receptivity exists, either in the form of facultative contemplation or methodical study, the pleasure intertwines with knowledge moment by moment. Thus, it is the viewer’s competence that ultimately decides the level of the aesthetic experience. Nevertheless, regardless of whether reception is closer to or farther away from complete reception, democracy has decided to allow a large amount of tolerance towards all the receptors of the arts, because the diversity of aesthetic experiences, even in terms of quality, does not do any harm. The problem arises when aesthetic reception does not take place at all, coming to a halt at the stage of visual perception. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |