Form, image, imagery and love of geometry

Form, image, imagery, and love of geometry

| In principle, if we feel that we are in the presence of a work of art, then that really is a work of art. I think so. It presents itself to us first as form. Some architects, more non-Latin architects, are unable to reconcile themselves completely with the visual side of things. Neither can I yet, morally or emotionally. But neither can we resist the importance of form when it comes to the visual arts. |

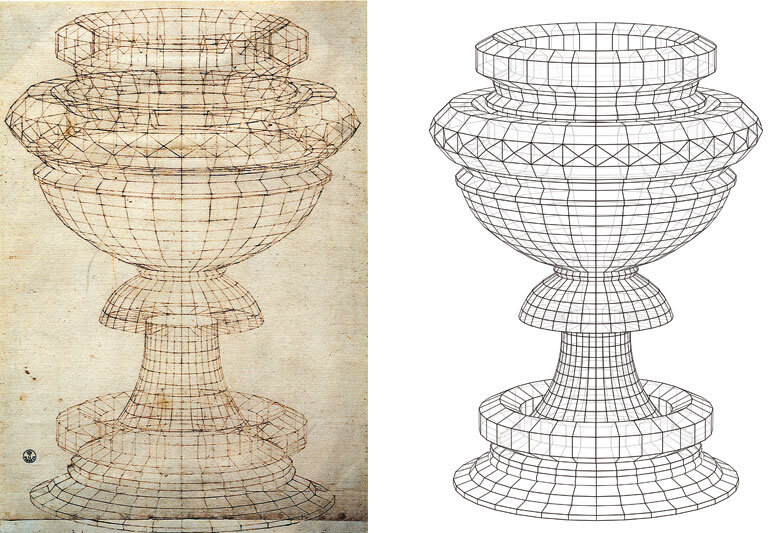

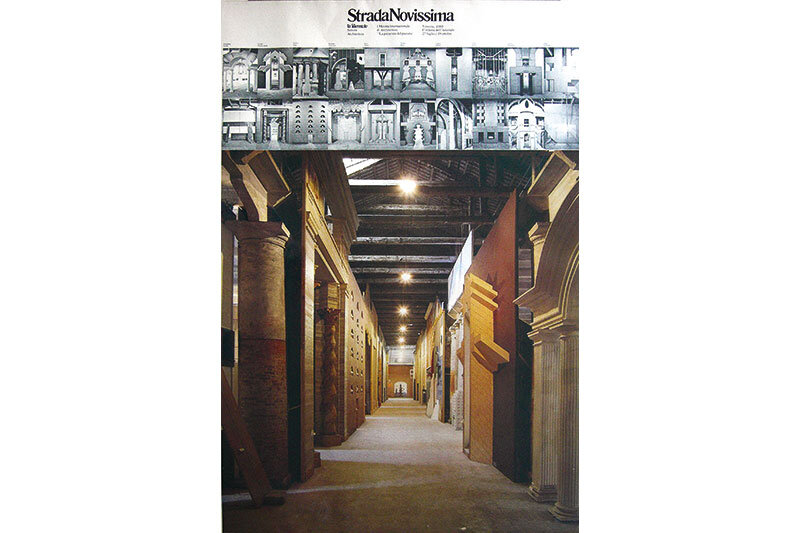

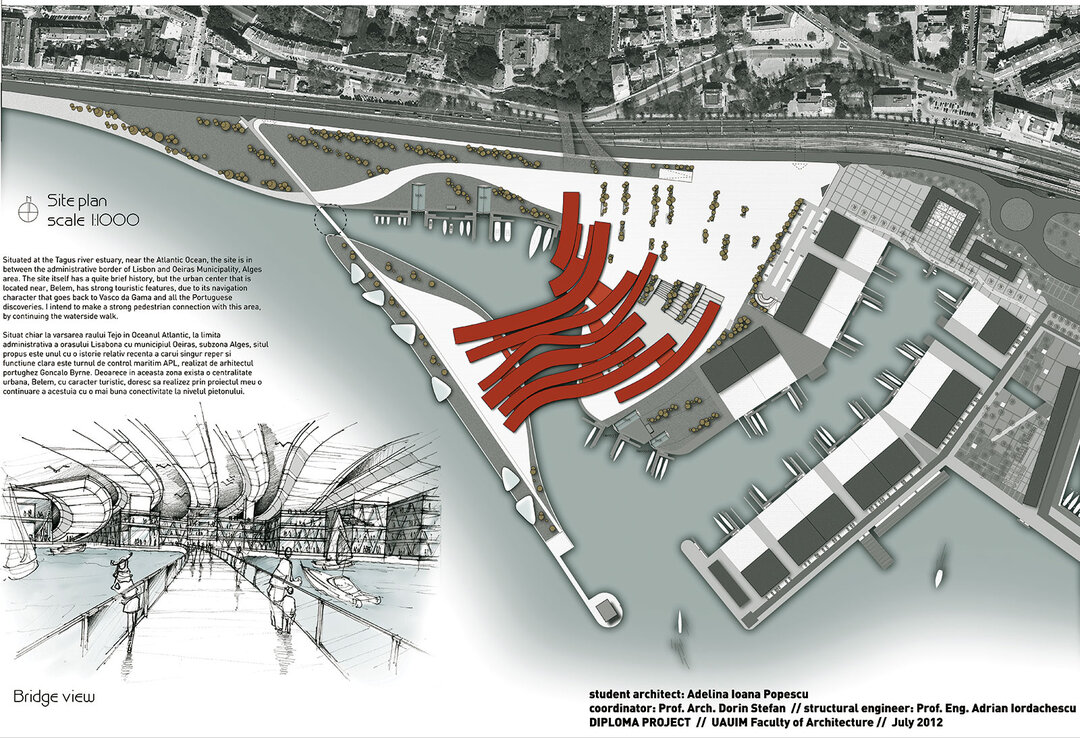

| In the first place, because what first moves us in the presence of an object suspected of being art is form, that is, a certain alchemy of lines, colors, light, space, surfaces. But, associated with this appearance, there is something else which arouses the aesthetic reaction, a common quality which must be shared by an Etruscan vase, a Gaugain painting, an Anatolian carpet, the stained-glass windows of Chartres, an Olmec sculpture, Fra Angelico's frescoes and the chapel of Ronchamp. It is the intuition that behind the visual is a story, told for those with ears to hear, but which first needs a certain force to penetrate beyond the surface layer of form. And if it is a work of art, it finds confirmation there. We complain today about the prevalence of image over value. We fear, it seems, for art's nimbus of nobility, given by meaning. So we fear not so much the prevalence of form over semantic value as the prevalence of images over forms and values. The image of a value is called prestige, and the image of a form is called representation. We are afraid of false prestige and self-sufficient representations, created by professionals of imagery - sociologists or photographers. We fear not for ourselves, but we fear for our students, happy to fall into the traps of powerful images. Architectural representations are to our students like Lorelei, and they paddle through publications without seeing - hidden for them in the depths - the text. Meaning. In fact, because the professionals strive to make their images so retinal, for the public at large the visual is often enough, instead of the aesthetic experience. This is what we fear. We don't fear the distortions our subjectivism produces when in contact with the art form, because scholars have legitimized it for us, and we think we control it. The rest, which we call subjectivity, we accept almost with pride. We assume the derogations that our visual perception, never one hundred percent purely visual but contaminated through the filter of the ineffable canvas that is our own imaginary, allows us to make. Scientists have ventured to investigate the inevitable degree of opacity of form in its encounter with the visual. Rudolf Arnheim, for example, analyzed the dynamic interaction of visual forces and their influence on perception. What also matters is the level of intellectualization of the work, which ranges from an assimilated cultural product to an avant-garde object that defies the established principles of composition. Perception also depends on the conjunctural hypostasis of the subjects, which may or may not allow the installation of a state of orientation favorable to aesthetic reception. Admitting that the state of receptivity exists, whether in the form of optional contemplation or methodical study, enjoyment is intertwined moment by moment with knowledge. Thus it is the viewer's competence that ultimately decides the level of aesthetic experience. And yet, irrespective of whether reception is further from or closer to full reception, democracy has decided to be tolerant towards all art receptors, because the diversity of aesthetic experiences, even in terms of quality, does no harm. The problem arises when aesthetic reception no longer even takes place, it stops at the stage of visual perception. |

| Read the full text in Arhitectura 4/2012 |

| In principle, if we feel that we are in the presence of a work of art, then that thing really is a work of art. That's what I think. First of all it presents itself to us as a form. Some non-Latin architects can't really get along with the visual side of things. Nor am I able to yet, either morally or sentimentally. But that doesn't mean we can go against the importance of form when we talk about the visual arts. |

| In the first place, this is because what moves us when we're in the presence of an object suspected of being art is its form, i.e. a certain alchemy of lines, colors, light, space, surfaces. But combined with this appearance there is also something that evokes an aesthetic reaction, a shared quality possessed by an Etruscan vase, a Gauguin painting, an Anatolian rug, Chartres stained glass windows, an Olmec statue, Fra Angelico frescoes, and the Ronchamp Chapel. It is the intuition that behind the visual there is a story told for those that have ears to hear, but which first of all requires the strength to pierce through the superficial layer of form. And if it is a work of art, it will find its confirmation there. Nowadays we complain about the prevalence of image over value. It's apparent that we fear for the nimbus of nobility that meaningfulness lends art. We are not so much afraid of the prevalence of form over semantic value as much as we are afraid of the prevalence of images over forms and values. We are afraid of fake prestige and self-sufficient representation, created by image professionals: sociologists and photographers. We're not afraid for our own sake, but for the sake of our students, who so blithely succumb to the snares of powerful images. To our students, architectural representations are like the Loreley, and they row through publications without seeing the text, hidden from them in the depths. Which is to say, without seeing the meaning. In fact, because the professionals strive to make their images so retinal, the visual rather than aesthetic experience is often sufficient for the public as a whole. We're not afraid of the distortions that our subjectivism produces on contact with artistic form, because the scholars have legitimized it for us, and we think that we control it - to a certain degree. As for the rest - what we call subjectivity - we accept it almost with pride. We accept the derogations permitted by our visual perception, which is never one hundred per cent visual, but contaminated through the filter of the ineffable gauze that is our own imagination. The scholars have ventured to investigate the inevitable degree of opacity of form in the encounter with the visual. Rudolf Arnheim, for example, has analysed the dynamic interaction of visual forces and their influence on perception. What also counts is the level of intellectualisation in a work, which ranges from assimilated cultural product to avant-garde object, defiant towards the established principles of composition. Perception also depends on the circumstantial hypostasis of the subject, which may or may not allow a state of orientation favourable to aesthetic reception. If we allow that the state of receptivity exists, either in the form of facultative contemplation or methodical study, the pleasure intertwines with knowledge moment by moment. Thus, it is the viewer's competence that ultimately decides the level of the aesthetic experience. Nevertheless, regardless of whether reception is closer to or farther away from complete reception, democracy has decided to allow a large amount of tolerance towards all the receptors of the arts, because the diversity of aesthetic experiences, even in terms of quality, does not do any harm. The problem arises when aesthetic reception does not take place at all, coming to a halt at the stage of visual perception. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |