București. În căutarea identității vizuale

BUCHAREST. IN SEARCH OF LOST IDENTITY

| BUCUREȘTIUL ESTE IMPOSIBIL DE DESCRIS CU O SINGURĂ SINTAGMĂ. ÎNCERCÂND SĂ ÎI DEFINIM IDENTITATEA, DESCOPERIM DIVERSITATEA DE STILURI ARHITECTURALE, PREZENȚA, ÎNCĂ PALPABILĂ, ÎN ȚESĂTURA ORAȘULUI A EVOLUȚIEI SALE ÎN TIMP, HAOSUL SPAȚIULUI PUBLIC, CULORILE CONTRASTANTE, VITALITATEA. |

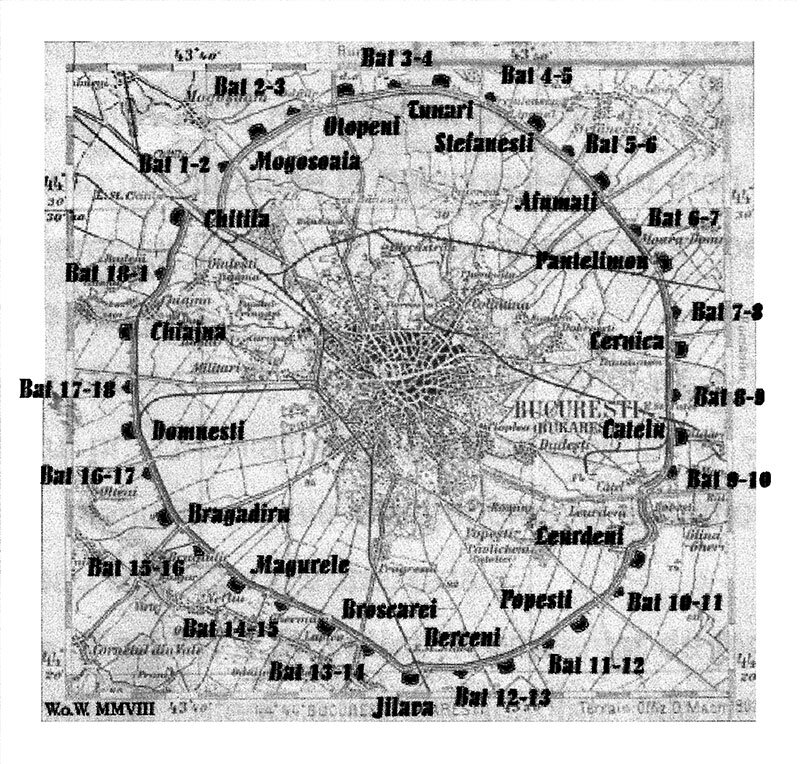

| Pentru Ștefan Baciu, Bucureștiul este, în egală măsură, un oraș urât și fascinant: „Cât te urăsc, orașul meu iubit,/Cât te râvnesc, când nu sunt lângă tine,/Căci cu o albă lamă de cuțit/Otrava ta mi-ai încrustat-o-n vine”1. Dana Harhoiu îl descoperă ca „oraș al destinului și vocației europene, oraș martirizat de puterea totalitară,(....) un oraș care trebuie înțeles, gândit și refăcut.... Bucureștiul s-a dezvoltat asimilând influențe orientale, printr-o capacitate de integrare naturală care i-a susținut vocația de a fi un oraș între Orient și Occident”2. Bucureștiul emoționează călătorii străini: Paul Morand crede că lecția pe care ne-o oferă „nu e o lecție de artă, ci una de viață; el te învață să te adaptezi la toate, chiar și la imposibil”3, în timp ce Catherine Durandin spunea că Bucureștiul nu este „un mic Paris, însă forfoteala sa, contrastele sale arhitecturale, intruziunile ruralului în inima sa și cartierele dezarticulate incită imaginația să creeze o coerență. Această coerență nu este arhitecturală, ci afectivă” 4.Indiferent de context, încercarea de a defini Bucureștiul pornește întotdeauna de la prezența sa istorică, sâmburele în jurul căruia se definește orașul contemporan. Bucureștiul istoric, 14% din suprafața orașului5, concentrează valorile arhitecturale, ambientale și culturale care îi creionează unicitatea. Dacă se poate vorbi despre o identitate palpabilă a Bucureștiului, ea se regăsește în cartierele istorice, cu aerul lor patriarhal, cu amestecul lor de stiluri arhitecturale, cu fațadele decorate, cu grădini private, cu parcursul sinuos al străzilor. Bucureștiul cartierelor istorice, neglijat sau demolat de administrația comunistă pentru a face loc proiectelor sale faraonice, a devenit, în perioada postdecembristă, ținta predilectă a speculației imobiliare. În ultimul deceniu, numeroase intervenții urbane derogatorii au distrus coerența urbană a vechiului București, conducând la degradarea calității vieții locuitorilor și la pierderea unor repere istorice și culturale.Astăzi, discursul public despre patrimoniul Bucureștiului este disfuncțional, rupt de realitate. Experții vorbesc despre patrimoniul orașului ca și cum acesta ar fi doar o înșiruire de „obiecte” disparate, înscrise sau nu pe Lista Monumentelor Istorice. Investitorii, administrația publică și arhitecții ne explică în permanență că Bucureștiul este în permanentă devenire, că orașul are nevoie să se dezvolte cu orice preț. În eseul său „Să mai filosofăm puțin despre București”6, arhitectul Dorin Ștefan dezvolta teoria „devenirii urbane” a Bucureștiului: „Astăzi, Bucureștiul este blocat în prag. Va trebui să treacă pragul. Înapoi nu poate să mai meargă. (....) Să lăsăm orașul să-și urmeze cursul. Noi doar să-l «asistăm critic»”. O teorie elegantă, contrazisă însă de realitatea cotidiană a străzii, devenită o junglă în care noul anihilează vechiul. „(...) Situarea complexă, transistorică și transindividuală”7 a orașului despre care vorbește Dorin Ștefan se manifestă prin demolări de imobile cu arhitectură valoroasă și prin intervenții urbane brutale asupra țesutului istoric. La umbra teoriei, realitatea se dovedește a fi agresivă, inestetică, indiferentă la valorile trecutului. Cuvântul de ordine al acestei „deveniri” asistate este, din păcate, lipsa de respect față de istoria locului. Orașul istoric și locuitorii săi se află astăzi într-o luptă surdă pentru supraviețuire.Cu toate acestea, nici Primăria Municipiului București (PMB), nici organizațiile profesionale nu au făcut încă o evaluare a efectelor urbanismului derogatoriu asupra coerenței zonelor construite protejate. Din studiile de caz documentate de Asociația Pro.Do.Mo8 rezultă că o mare parte din noua arhitectură ignoră nu numai legislația internațională de protecție a patrimoniului, ci și legislația națională, mai permisivă.Discursul public nu reflectă realitatea, ci o ocultează.

Pentru a da Bucureștiului șansa să intre în competiție cu alte capitale europene și pentru a inspira în bucureșteni loialitate față de orașul natal sau de adopție, zonele istorice trebuie protejate cu orice preț. Astfel, viitorul Plan Urbanistic General va trebui să întărească și să detalieze regulamentul zonelor protejate, nu să îl „flexibilizeze”. Derogările care au mutilat zonele protejate în ultimii ani nu trebuie să reprezinte punctul de pornire al unui nou Plan Urbanistic Zonal. Printre propunerile care ar îmbunătăți calitatea intervențiilor în zonele construite protejate este și înființarea unei Comisii a Bucureștiului Istoric, care să evalueze proiectele din punctul de vedere al coerenței urbane și al conservării patrimoniului construit. În prezent, proiectele sunt evaluate numai din punct de vedere tehnic de Comisia Tehnică de Urbanism și Amenajarea Teritoriului din cadrul PMB. Nu există niciun control asupra esteticii noilor imobile și rareori sunt respectate condiționalitățile referitoare la materialele de construcție și la crearea unei arhitecturi adecvate caracterului zonei. Nici membrii Comisiei Monumentelor Istorice, nici membrii CTUAT nu evaluează proiectele in situ și pe baza unor studii de impact asupra coerenței zonei. Pe de altă parte, Primăria mimează consultarea publică și ignoră sistematic criticile și protestele locuitorilor. În realitate, nicio instituție publică nu este responsabilă de modul cum se dezvoltă zonele construite protejate, ceea ce permite investitorilor privați să „interpreteze” regulamentul urbanistic în interes propriu. O mai bună reglementare a procesului de avizare și o largă participare publică sunt ingrediente necesare, dar nu suficiente, pentru conservarea zonelor protejate. Lipsește cadrul economico-financiar care să stimuleze elaborarea proiectelor de conservare și restaurare. Acest cadru trebuie să cuprindă subvenții publice, scutiri de impozite, garanții financiare, împrumuturi pe termen lung și o reglementare clară a parteneriatului public-privat, care să condiționeze concesionarea terenurilor publice promotorilor imobiliari de conservarea și restaurarea patrimoniului construit. Una dintre sursele de finanțare pentru regenerarea urbană a zonelor istorice este Uniunea Europeană, cu condiția ca administrația publică să înțeleagă importanța conservării identității istorice a orașului și să aibă capacitatea administrativă de a gestiona proiecte urbane complexe. Primul pas în atragerea de fonduri de dezvoltare a cartierelor cu valoare arhitecturală este, însă, inventarierea tuturor imobilelor și a spațiilor libere publice și private. Acest pas nu a fost făcut, încă, de către PMB care, în ultimii 12 ani, a inventariat numai 12 zone protejate din cele 98 legiferate. În schimb, a inițiat un proiect de cartare a trei zone protejate9, care, dacă va fi adoptat de Consiliul General, ar reprezenta o derogare de la regulamentul zonelor protejate prin creșterea indicatorilor urbanistici. Lipsește o abordare coerentă a dezvoltării cartierelor istorice la nivelul administrației locale. În opinia noastră, a Asociației Pro.Do.Mo și a Asociației Salvați Bucureștiul, inițiatorii proiectului de voluntariat Inventarul zonelor construite protejate10, evaluarea cantitativă a zonelor istorice este o condiție esențială pentru inițierea unor proiecte coerente de regenerare urbană pe baza unor analize socio-economice pertinente. Educația este o altă pârghie importantă în efortul de conservare a zonelor istorice. În experiența noastră, conceptul de zonă construită protejată este necunoscut publicului larg, inclusiv locuitorilor din cartierele istorice. Nu există nicio instituție publică care să fie responsabilă cu informarea și consilierea proprietarilor din zonele construite protejate, în schimb, instituțiile implicate în aprobarea documentațiilor de urbanism (Primăria Municipiului București, Direcția de Cultură și Patrimoniu Național a Muncipiului București, Ministerul Culturii și Patrimoniului Național și Ministerul Dezvoltării și Administrarea Teritoriului) joacă ping-pong birocratic cu responsabilitatea avizării. Acest articol este o pledoarie în favoarea conservării și regenerării urbane a zonelor construite protejate11, singurul instrument de conservare a identității orașului. Pentru societatea civilă, zonele protejate nu sunt un concept birocratic, imposibil de aplicat, sau „pragul” care blochează dezvoltarea economică a orașului. Pentru noi, zonele istorice configurează identitatea Bucureștiului, pe care trebuie să construim viitorul. |

| Note: |

| 1. Ștefan Baciu, Cetatea lui Bucur, lyrics, „București!”, Humanitas Publishing House, 2006.2. Dana Harhoiu, București, Un oraș între Orient și Occident, p. 13, Simetria Publishing House, Arcub, 2001.3.Paul Morand, București, p. 235, Echinox Publishing House, 2000.4. Catherine Durandin, București, Amintiri și Plimbări, p. 139, Paralela 45 Publishing House, 2003.5. „Zone Protejate Construite - Municipiul București și teritoriul administrativ”, „Ion Mincu” Institute of Architecture Bucharest - 1997, architect Dan Marin, architect Florinel Radu.

6. Bucureștiul Ascuns, „Să mai filosofăm puțin despre București”, architect Dorin Ștefan, Igloomedia Publishing House, 2010. 7. Ibidem. 8. Patrimoniul Bucureștiului. Raport 2008-2012, Asociația Pro.Do.Mo, www.prodomo.org /urbanism/proiecte/proiecte_1.php 11. HCGMB nr. 279/2000, http://www.pmb.ro/servicii/urbanism/zone-protejate/z_aprobate.php |

| BUCHAREST IS IMPOSSIBLE TO DESCRIBE IN ONLY ONE WORD. WHEN WE ATTEMPT TO DEFINE ITS IDENTITY, WE DISCOVER ITS DIVERSE ARCHITECTURAL STYLE, THE PRESENCE, STILL PALPABLE, IN THE TISSUE OF THE CITY, OF ITS EVOLUTION OVER TIME, THE CHAOS OF THE PUBLIC SPACE, THE CONTRASTING COLORS, THE VITALITY. |

| For Ștefan Baciu Bucharest is an ugly, as well as fascinating, city: “How much I loathe you, my beloved city, /How much I need you, when I am not near you, /As in the wound you cut with a white blade/You poured the poison running through my veins”1. Dana Harhoiu describes it as a “a city of European destiny and vocation, martyred by the totalitarian power,(....) a city which needs to be understood, thought over and rebuilt... Bucharest has developed by assimilating Oriental influences, thanks to a capacity of natural integration which has supported its vocation of city caught between the East and the West”2. Bucharest has deeply moved foreign travelers: Paul Morand believed that the lesson this city taught us “is not a lesson in art, but a lesson in life; it teaches you to adapt to anything, even to the impossible”3, while Catherine Durandin noted that Bucharest is not “a little Paris; however, its hustle and bustle, its architectural contrasts, the intrusion of country life in its very heart and its disjointed districts invite the imagination to create a coherent entity. This coherence is not architectural, though; it is emotional”4.Irrespective of the context, the attempt to define Bucharest always starts from its historical presence, the kernel around which the contemporary city is defined. Historical Bucharest, 14% of the city area5, concentrates the architectural, ambiance and cultural values which make it unique. If we must refer to a tangible identity of Bucharest, then it can definitely be found in the historical districts, with their patriarchal air, their mix of architectural styles, the decorated facades, the private gardens and the winding trajectory of the streets. The Bucharest of historical districts, neglected or demolished by the communist administration to make room for its pharaonic projects, has become, in the post-December ’89 period, the favorite target of real estate speculation. In the last decade, numerous illegal urban interventions have destroyed the urban coherence of the old Bucharest, leading to the degradation of the life of its inhabitants and to the loss of historical and cultural landmarks.Nowadays the public discourse on the patrimony of Bucharest is dysfunctional and utterly cut off from reality. The experts refer to the city patrimony as if it were a mere string of disparate “objects”, registered or not on the List of Historical Monuments. The investors, the public administration and the architects permanently explain to us that Bucharest is subject to ongoing change; that the city needs to develop at all costs. In his essay “Să mai filosofăm puțin despre București” (Let us speculate a little more about Bucharest)6, architect Dorin Ștefan developed the theory of Bucharest’s “urban becoming”: “Today Bucharest is stuck on the threshold. It will have to cross it though. There is no turning back for it. (....) Let us leave the city to follow its course, and let us just «assist it critically»”. It is an elegant theory, which is contradicted, however, by the daily reality of the street, practically a jungle where the new is doing away with the old. “(...) The complex, trans-historical and trans-individual location”7 of the city, referred to by Dorin Ștefan, expresses itself through demolitions of buildings evincing valuable architecture and through brutal urban interventions on the historical tissue. In the shade of theory, reality turns out to be quite aggressive, unaesthetic, and indifferent to the values of the past. The essential word which best summarizes this assisted “becoming” is, unfortunately, the lack of respect towards the history of the place. The historical city and its inhabitants are nowadays engaged in a silent war for survival.However, neither the Bucharest City Hall (PMB), nor professional organizations have performed an assessment of the effects of illegal city planning on the coherence of the protected built up areas. The case studies documented by Pro.Do.Mo Association8 show that a large part of the new architecture ignores not only the international laws regarding protection of the patrimony, but also national and more permissive, laws.Public discourse does not reflect reality at all; it conceals it.

In order to give Bucharest the chance to enter into a competition with other European capitals and to infuse Bucharest dwellers with loyalty towards their native or adoptive city, historical areas must be protected at all costs. Thus, the future General Urban Plan will need to consolidate and to further detail the regulation on protected areas, not to render it “more flexible”. The derogations which have maimed the protected areas during the last years should not represent the starting point of a new Zonal Urban Plan. One of the proposals which could improve the quality of interventions in the protected built up areas is the establishment of a Commission of Historical Bucharest, which would evaluate the projects in terms of urban coherence and preservation of the built-up patrimony. At present, such projects are only assessed from a technical standpoint by the Technical Urban Planning and Land Development Commission within PMB. There is no control over the aesthetics of the new buildings and the requirements concerning the construction materials and the creation of architecture in line with the character of the area are rarely observed. Neither the members of the Historical Monuments Commission, nor the members of CTUAT evaluate the projects in situ and on the basis of impact studies on the coherence of the area. On the other hand, the City Hall mimes public consultation and systematically ignores the criticism and protests raised by the inhabitants. In point of fact, no public institution is responsible for the manner in which built up protected areas are developed, which allows private investors to “interpret” the urban planning regulation for their own benefit. A better regulation of the endorsement process and larger public involvement are necessary, but not sufficient to preserve the protected areas. What is missing is the appropriate economic and financial framework which would encourage preservation and restoration projects. Such framework needs to contain public subsidies, tax exemptions, financial guarantees, long-term loans and a clear regulation of the public-private partnership, which would condition the concession of public land to real estate promoters on the preservation and restoration of the built up patrimony. One of the financing sources of the urban regeneration of historical areas is the European Union, provided that public administration understands the importance of preserving the historical identity of the city and possesses the administrative capacity to manage complex urban projects. Yet the first step to attract funds for the development of districts with architectural value is to make an inventory of all vacant buildings and premises, be they public or private. However, this step has not been taken yet by PMB which, during the last 12 years, has made an inventory containing only 12 protected areas from the 98 provided by law. Instead, it initiated a map drawing project for three protected areas9 which, if adopted by the General Council, would amount to a derogation from the regulation of protected areas through an increase in urban planning indicators. What is missing is a coherent approach by local administration authorities to the development of historical districts. We, the Pro.Do.Mo Association and Salvați Bucureștiul Association, initiators of the voluntary project An Inventory of Built up Protected Areas10, are of the opinion that the quantitative assessment of the historical areas is an essential condition to the initiation of coherent urban regeneration projects based on relevant socio-economic analyses. Education is another important factor in the effort to preserve historical areas. According to our experience, the concept of built up protected area is unknown to the public at large, including to the inhabitants of historical districts. No public institution is responsible for the information and guiding of owners in the built up protected areas; instead, the institutions involved in the approval of urban planning documentation (Bucharest City Hall, The Directorate for Culture and National Patrimony of the Bucharest Municipality, the Ministry of Culture and National Patrimony and the Ministry of Development and Land Management) play a bureaucratic game of Ping-Pong with the liability for the opinions issued. This article is a plea in favor of the urban preservation and regeneration of protected built-up areas11, the only tool for preserving the identity of the city. For civil society protected areas are not a bureaucratic, impossible to apply project or the “threshold” which blocks the economic development of the city. For us, historical areas are those areas which shape the identity of Bucharest, on which we must build the future. |

| Notes: |

| 1. Ștefan Baciu, Cetatea lui Bucur, lyrics, „București!”, Humanitas Publishing House, 2006.2. Dana Harhoiu, București, Un oraș între Orient și Occident, p. 13, Simetria Publishing House, Arcub, 2001.3.Paul Morand, București, p. 235, Echinox Publishing House, 2000.4. Catherine Durandin, București, Amintiri și Plimbări, p. 139, Paralela 45 Publishing House, 2003.5. „Zone Protejate Construite - Municipiul București și teritoriul administrativ”, „Ion Mincu” Institute of Architecture Bucharest - 1997, architect Dan Marin, architect Florinel Radu.

6. Bucureștiul Ascuns, „Să mai filosofăm puțin despre București”, architect Dorin Ștefan, Igloomedia Publishing House, 2010. 7. Ibidem. 8. Patrimoniul Bucureștiului. Raport 2008-2012, Asociația Pro.Do.Mo, www.prodomo.org /urbanism/proiecte/proiecte_1.php 11. HCGMB nr. 279/2000, http://www.pmb.ro/servicii/urbanism/zone-protejate/z_aprobate.php |

FOTOGRAFII:

IOANA MARIA RUSU

Moara lui Assan București

Zona Berzei-Buzești București / Area Berzei-Buzești Bucharest

Zona Berzei-Buzești București / Area Berzei-Buzești Bucharest

Zona Berzei-Buzești București / Area Berzei-Buzești Bucharest

Zona Berzei-Buzești București / Area Berzei-Buzești Bucharest

Zona Berzei-Buzești București / Area Berzei-Buzești Bucharest