Patrimoniofobia: falsa dilemă a conflictului dintre dezvoltare și conservarea patrimoniului

HERITAGE-PHOBIA. A FALSE DILEMMA IN THE CONFLICT BETWEEN DEVELOPMENT AND HERITAGE PRESERVATION

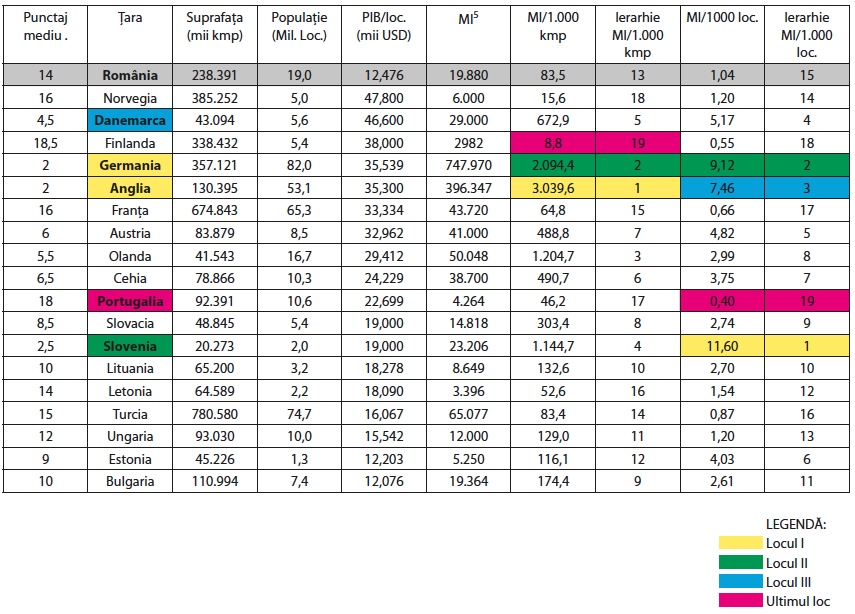

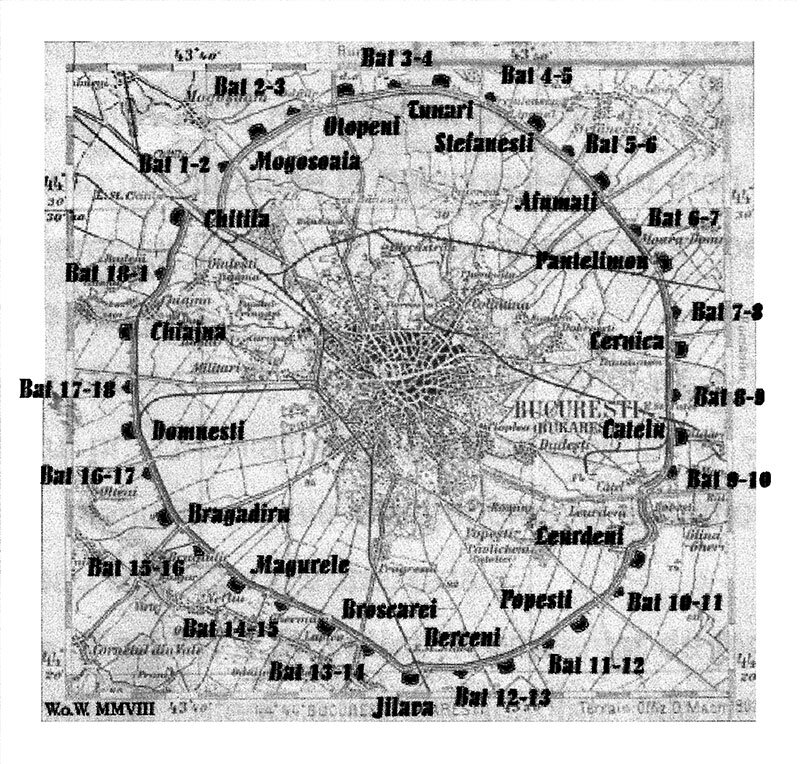

| De ceva timp sunt voci care spun că în Lista Monumentelor Istorice din România - și cu precădere în București - ar fi prea multe monumente istorice. Că rezonabil ar fi să se mai reducă din ele, pentru a putea dezvolta liber teritoriul, încorsetat de rigorile protejării clădirilor clasate. Scoaterea acestora din Lista Monumentelor Istorice ar avea același efect benefic ca acela clamat cu cinism nu de mult pentru „scoaterea din sistem” a pensionarilor. După 23 de ani de tranziție spre economia de piață, timp în care rezultatele în nivelul de trai și calitatea vieții noastre sunt relativ modeste, s-a descoperit în sfârșit ce ne împiedica a ajunge din urmă țările care, plecând în același timp cu noi din „lagărul socialist”, au ajuns sensibil mai departe. Cauza ar fi existența supranumerică a patrimoniului construit, cu precădere cel urban, sau cel care stă nefericit pe traseul marilor și întârziatelor (din această privință, probabil) șantiere de infrastructură.

Tehnica este veche: dacă bugetele statelor sau oamenii sărăceau ori economia era în criză, vina nu stătea în activitatea politicienilor, administratorilor sau autorităților, ci, după caz, la burghezi, la străini, la evrei ori - dacă nici burghezi, nici străini și nici evrei nu erau - la contextul geopolitic nefericit. Astăzi, prin poziții publice, în conferințe, ședințe de avizare ori în Parlament soluția care ni se oferă pentru repornirea economiei este modificarea listei monumentelor istorice (cel puțin în București), schimbarea sistemului de avizare astfel încât statului român să i se substituie grupuri private și locale de interese, ștergerea istoriei locurilor pentru a le putea extrage seva energetică sau de materii prime. Ce nu este spus de teoreticienii lui „development first” este că trendul pe care ni-l propun este exact opus nu doar celui exprimat de recomandări ori convenții internaționale (unele semnate chiar și de România), dar și celui consacrat de experiența recentă a țărilor pe care vrem să le ajungem din urmă din punct de vedere al calității vieții. |

| Citiți textul integral în numărul 2/2013 al revistei Arhitectura |

| Several voices have been heard lately claiming that the List of Historical Monuments in Romania, and especially in Bucharest, is too lengthy. That the reasonable thing to do would be to cut it down a little in order to allow free development of a land that is otherwise suffocated by the rigorous laws protecting historical buildings. Their deletion off the List of Historical Monuments would have the same beneficial effect as that cynical “removal of pensioners” from the system, claimed not long ago. After 23 years of transition to the market economy, during which time the results observed in the living standard and the quality of life are fairly modest, it has been finally discovered what has been preventing us from catching up with the countries which, while escaping the socialist prison concurrently with us, have nonetheless managed to go much farther. The cause would be the superabundance of the built heritage, especially in the urban areas, or of that heritage which unhappily stands in the way of the great and delayed (for this reason, probably) infrastructure building sites.

The technique is old: when state budgets or people grew poor or the economy went through a crisis, the fault did not lie with the activity of politicians, managers or the authorities, but, depending on the circumstances, with the bourgeois, the foreigners, the Jews or - if there were no bourgeois, foreigners or Jews - with the unhappy geopolitical climate. Nowadays, by means of public stances, in conferences, information meetings or in Parliament, the solution provided to give a new start to the economy is to amend the list of historical monuments (in Bucharest at least), to change the endorsement system so that the Romanian state may be replaced by private and local groups of interest, to delete the history of places in order to be able to extract their energy resources or raw materials. What the advocates of the “development first” theory fail to say is that this trend is opposed not only to that expressed by international recommendations or conventions (some of them even signed by Romania), but also to that consolidated through the recent experience of the countries we wish to catch up with in terms of life quality. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |