The architect's community versus the community architect

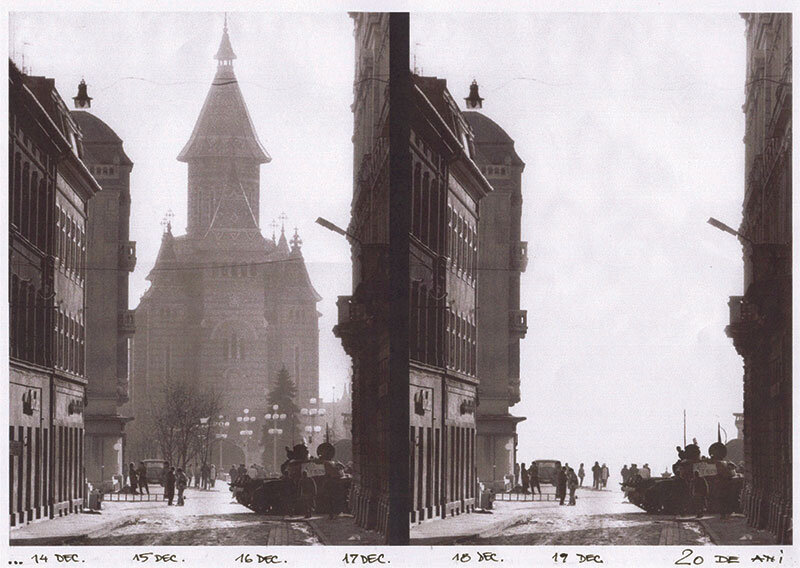

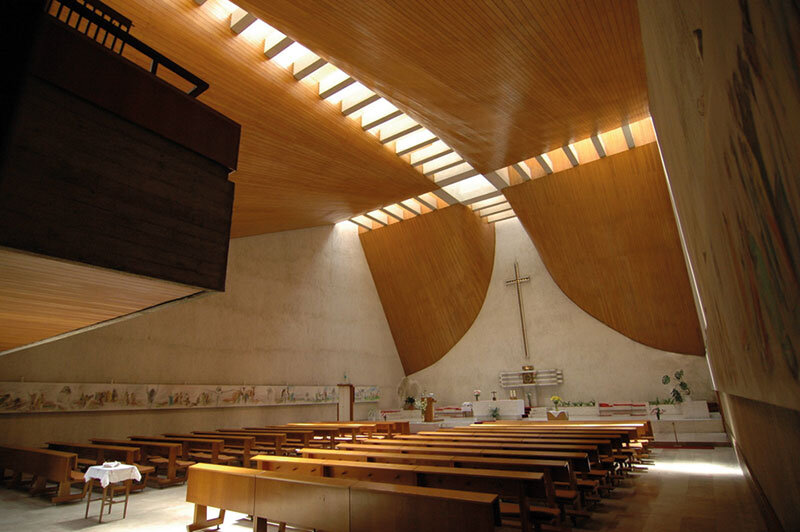

The Toledo Declaration (2010), adopted in the context of the emergence of the great financial-economic and social crisis, reinforced its focus on the quality of life of European Union citizens. This issue has been formalized by European governments because of the challenges facing European cities and structural changes caused by globalization, climate change, demographic change, etc. Special attention has been reaffirmed for 'deprived neighbourhoods in the context of the city as a whole', a commitment already made in the Leipzig Charter (2007) to reduce social and European polarization between communities within the same city. Urban regeneration plays the leading role in the new strategy adopted. It applies to the environmental, social, economic, cultural, architectural and urban planning environments. According to the abovementioned act, these goals can only be achieved through 'good governance', which seeks to optimize efforts and resources by strengthening cooperation, synergy and governance at all levels and adopting an integrated approach. These ideals can be achieved not only by 'reducing conflict and copying', but above all by encouraging collaboration between public and private actors, which should be geared towards 'revalorizing, reclaiming and even reinventing the existing city', thus optimizing the human, social, material, cultural and economic capital formed throughout history. Using these elements to build efficient, innovative, smart, more sustainable and socially integrated cities. Therefore, this strategic commitment to urban regeneration can only be achieved through an 'urban alliance', shared by all actors involved in the 'city-building' process : the finance sector, property owners, developers, politicians, public authorities, residents, experts, etc. The above-mentioned expert body encompasses many fields of activity. Of these, we are concerned with the role of architects and urban planners in this process. The role of these professions in the new alliance has been taught since the first lessons at university. Are we ready for the challenge of diminishing the copying of others? Is it right to educate the new generation by copying the London regeneration model around the Thames (except that we in Timisoara don't have abandoned docks), to copy the Bilbao model (except that we in Timisoara don't have an abandoned extractive industry), to copy the New York green space model (except that we don't have an abandoned surface subway line) or do we have the capacity to offer our own approach to our needs? Are we up to the challenge of lessening the conflict with the other actors involved in the act of reinventing the city? Is it right to educate the new generation of architects by copying the star model promoted by the Hollywood industry? Is it right to educate the new generation by copying the approach of modern urbanism, according to which "the architecture of cities was too important to be left to the citizens"?(Fishman, 1977) Therefore, over the years, as a trainer of future members of the corps of architects and urban planners (seen as a whole), I have tried, through new pedagogical methods, to bring about a change of attitude, namely that the architect and/or urban planner should serve the community, and not the other way around.

In a recently published article (Hanford, 2012a), E. Hanford recounts how D. Hestenes, a professor of physics at Arizona State University, demonstrated on the basis of experiments with students beginning after 1970 that, when assessing students' understanding of fundamental physics concepts on exams, the average pass rate among students did not exceed 40%. At that time, "most professors did not test (students) for this kind of understanding; students just had to solve problems to pass the exams." Together with other colleagues, Hestenes tried to find a way to test understanding of fundamental concepts. Today, although the information is everywhere, only 14% of students understand the fundamental concepts taught by traditional methods; Hestenes claims that "10% [...] learn anyway without any instructor. In principle, they learn by themselves", adding that most students "cannot passively assimilate knowledge" and as such, a method must be found to actively involve them in the learning process. The results of these studies were published in 1985, but were ignored for a long time. According to E. Hanford (Hanford, 2012b), the one who went further was E. Mazur (Mazur, 1997), a professor of physics at Harvard University, who claims that he set out to change the established method in universities. So, instead of giving traditional lectures, he proposes that students, after a preliminary reading of the topics, discuss the issues in small groups. In his experiments, for example, in a class of 100 students, he analyzed three possible answers to a problem; while only 29% of the students chose the correct answer on the first attempt, after discussion with the other students, the percentage of correct answers could rise to 62%. These techniques are referred to by E. Hanford (Hanford, 2012b) as "interactive engagement" techniques. The author also argues that, "in agreement with the results of Force Concept Inventory tests on tens of thousands of students from all parts of the world, most people who attend conventional courses end up with a poor grasp of fundamental concepts in physics". The originator of the new teaching methods, E. Mazur (Mazur, 1997) used an approach that he called "peer instruction" (the expression "peer instruction" has no exact equivalent in English, but refers to the development of individual intellectual and comprehension skills through constructive confrontation with the knowledge and opinions of peers in an informal environment and free dialog, where each member of the group is both teacher and learner. Similar expressions in Romanian, but which do not fully cover the meaning of the English expression, would be: "collective study", "co-learning", "mutual education", with the emphasis on the informal aspect of the relationship between colleagues). According to the above-mentioned study, students to whom the new teaching method has been applied claim that if traditional methods based on one-way transmission of information (from teacher to student) are maintained, there will be no need for faculties, because, thanks to modern technologies, information can be obtained as such at any time via the Internet.

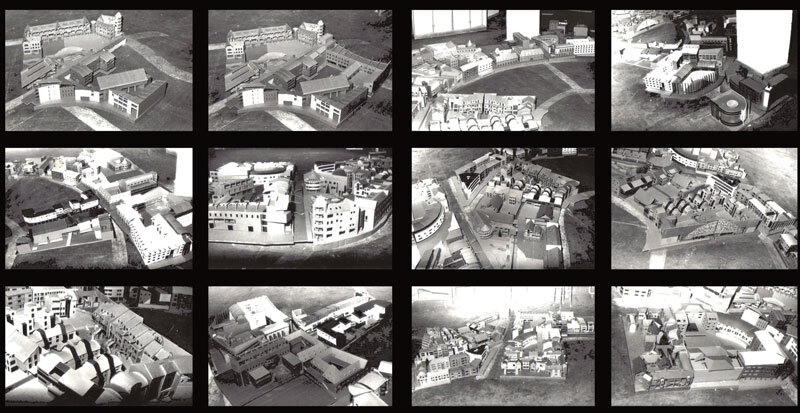

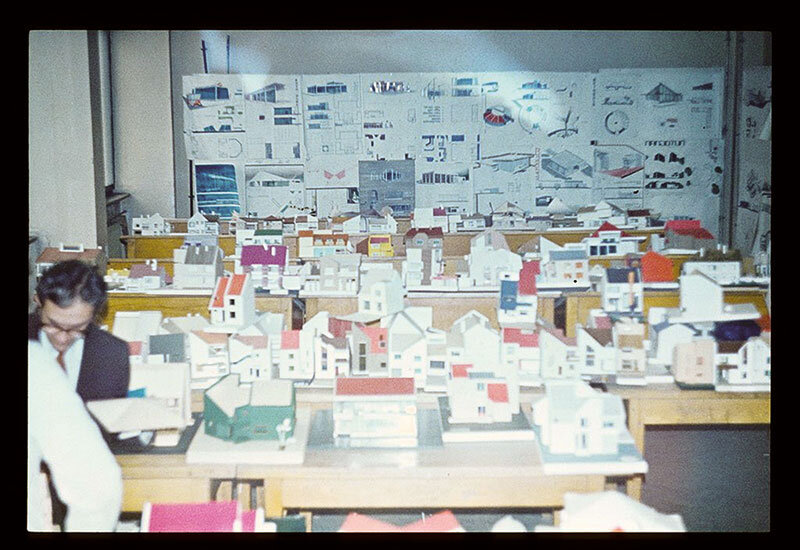

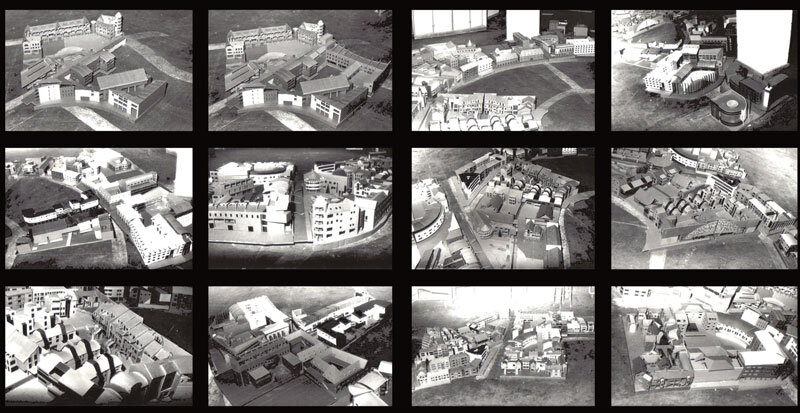

In the following, we will present a series of attempts to apply these methods, which are based on stimulating students' intuition and discovering fundamental realities through co-learning, applied to the specifics of our profession. These attempts have been carried out at the Polytechnic University of Timișoara, Faculty of Architecture, throughout our pedagogical experience.

Read the full text in issue 1/2013 of Arhitectura magazine - Special Issue Timișoara