Theresia Bastion, a cultural mall?

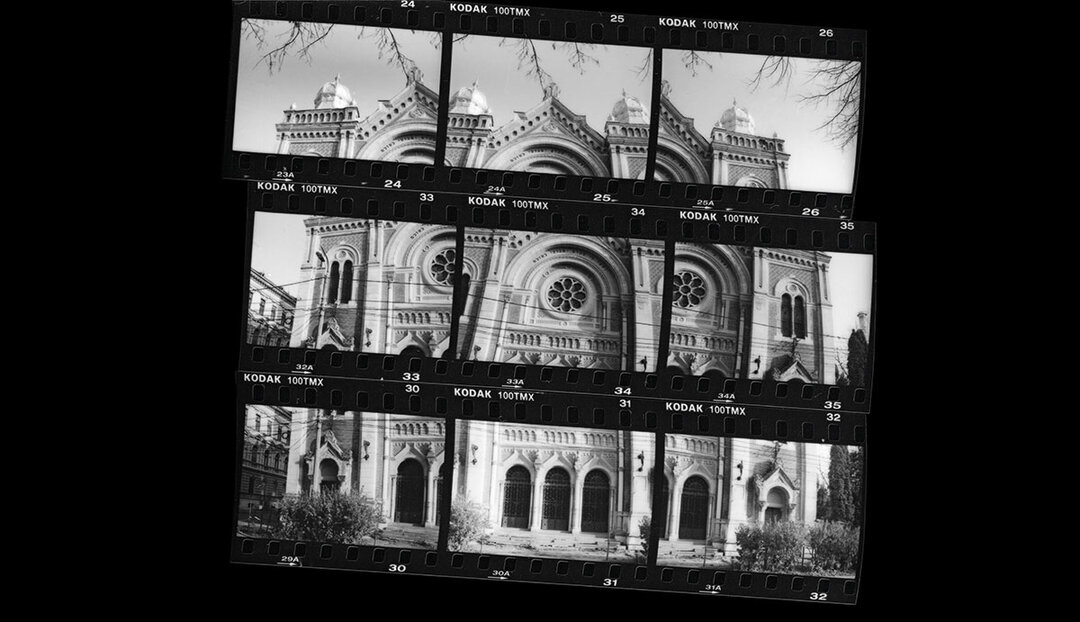

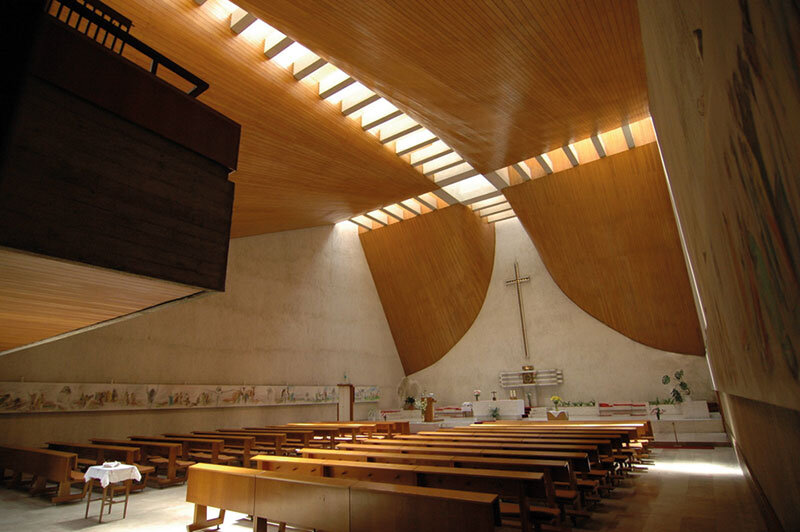

In the fall of 2010, only a few days after the protective fences separating Hector Street from the spectacle of the new architecture of the inner courtyard of the Theresia Bastion in Timișoara were dismantled, I noticed with surprise a new phenomenon for the urban geography of a Romanian city. At that moment, the still uninaugurated space of the courtyard of honor was quickly taken over by a number of groups of skaters and bikers, who nonchalantly and curiously carried out the first endurance tests of this new architecture. The response from the managers of this public space was equally swift. Before long, the courtyard and gangways of the historic building became the scene of some truly comical performances, starring the few public guards posted on duty. Literally running through the gangs and playful defiles of the new architecture any individual equipped with two or more wheels, they managed the feat of quickly ridding this public space of any form of spatial manifestation that did not fit into the norm. I perceived, with some sadness, this moment as a betrayal of the spatial ideals of the new architecture.

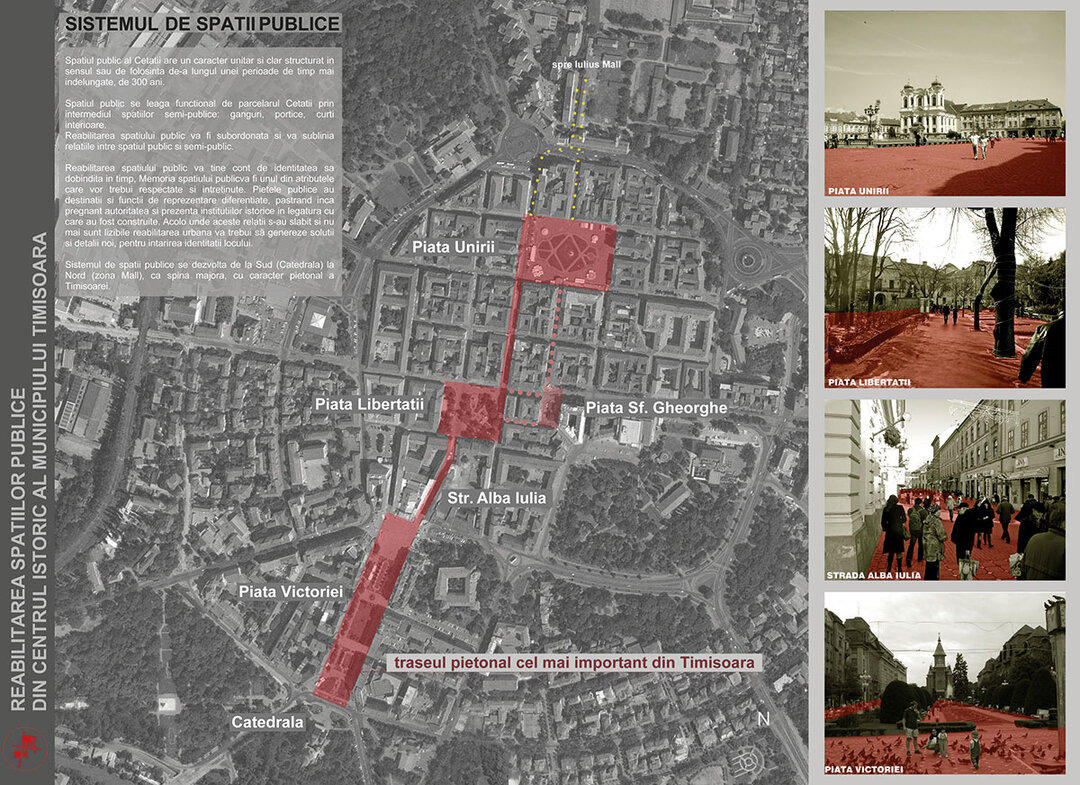

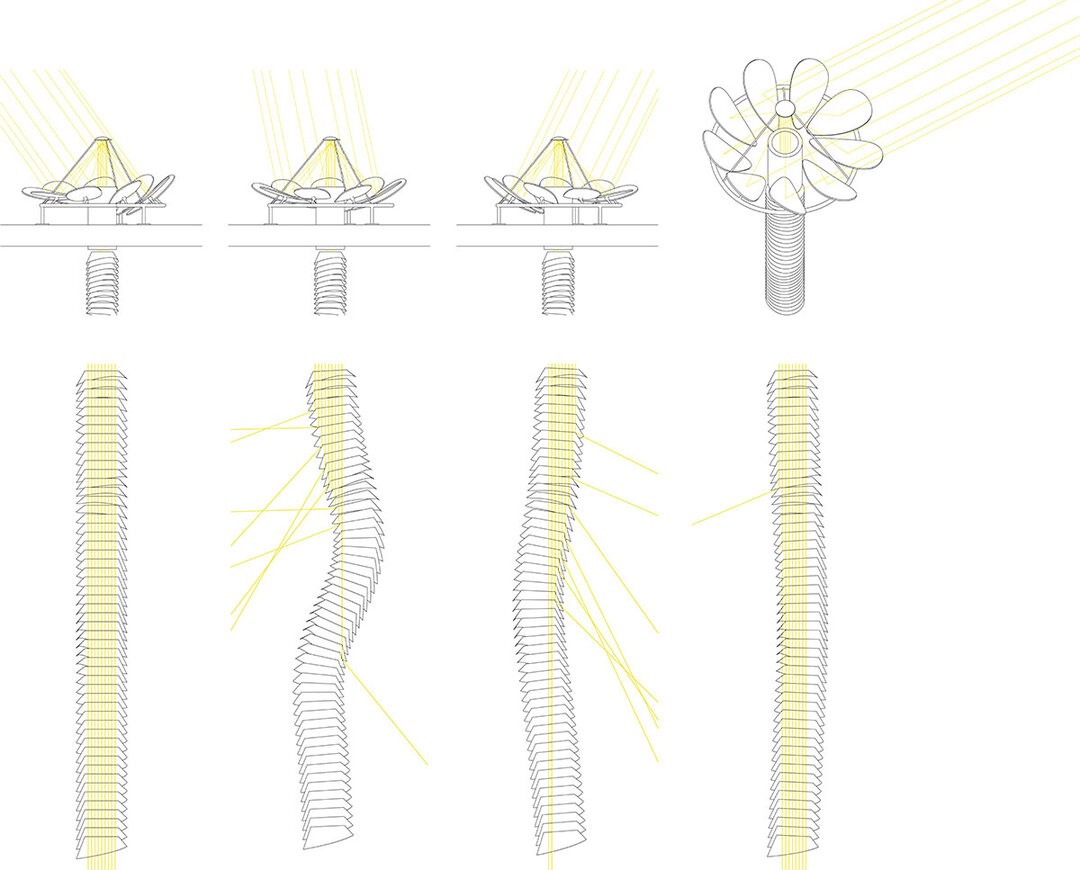

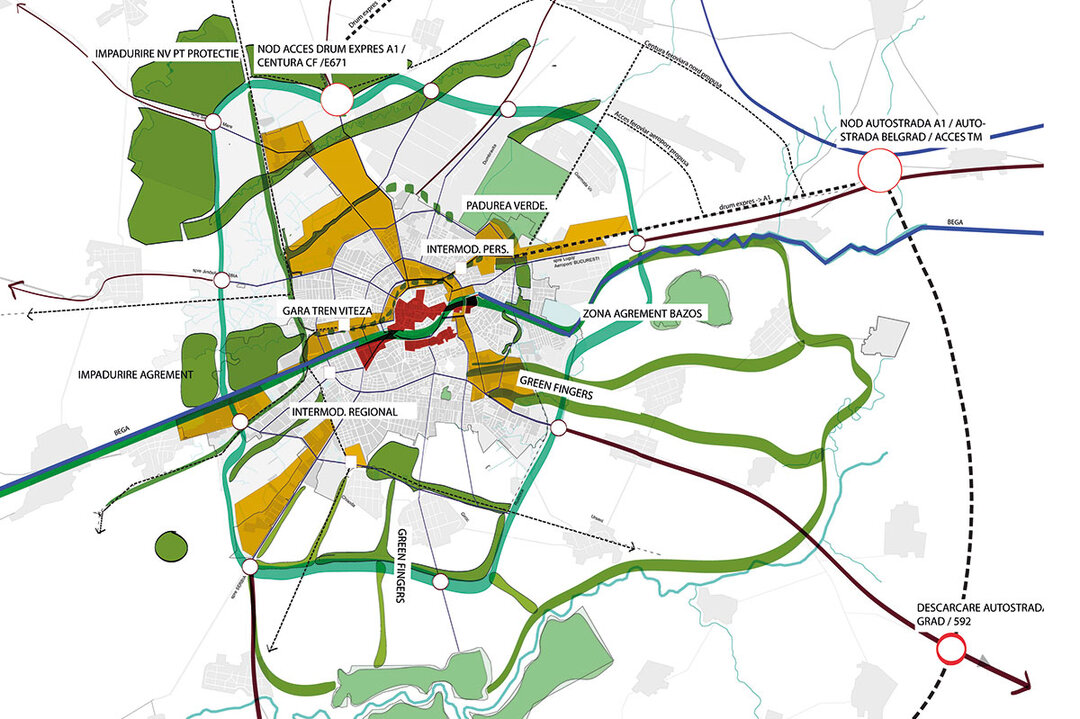

The transformation of this dynamic space, in the three short years since its inauguration, into a veritable zone of exclusion and control raised a series of questions for me, first of all, about the way public space is understood in Romania. Secondly, I wondered where are the activities I wanted to see in this space. Where is art, music, theater, who brings them, who maintains them, who consumes them. They still exist in the city's traditional spaces and institutions, but they have not migrated to this space, and when they have, it has been either temporary or inconsistent. Is it enough to have a space, a well 'planned' enclosure to stimulate these activities? The architectural quality of the newly generated space, its representative, symbolic, landmark character should have been, at least in our vision, the architects', sufficient to coagulate all these activities in this area. At the time of the inauguration, the beneficiary acquired an object designed, ironically, precisely to his own requirements, which he did not know how to capitalize on. This begs the question: if this is a flagship space, who is it really intended for and how is it being valorized? With an extremely favorable position in the geography of the city, at the confluence of several motorway and pedestrian arteries that circumscribe the central area, linking the university campuses to the south and north, benefiting from the proximity of the Faculty of Fine Arts and, in the future, the Faculty of Music, Theatre and Film, the ensemble should have been aimed at a highly dynamic target audience, coagulated around the creative segment of the city's population. The spaces of the reconfigured and architecturally unified historic buildings were to receive some of the pre-existing cultural functions as well as some new ones, while the new courtyard of honor, through the iconic, reference quality of the proposed architecture, was to transform this public space into an exterior support for the former.

Read the full text in issue 1/2013 of Arhitectura - Special Issue Timisoara

Bibliographical references:

Borden Iain, Skateboarding, Spaceand the City: Architecture and the Body Berg, Oxford, 2001.

Clarke D. B., The Consumer Society and the Postmodern City, London, Routledge, 2003.

Debord Guy, Society of the Spectacle, London, Rebel Press, 2010.

Hubbard Phil, City, New York, Routledge, 2006.

Lefebvre Henry, The Production of Space, Blackwell, Cambridge MA, 1991.

Merrifield Andy, Metromarxism, New York, Routledge, 2002.

Moore Alan, Art Gangs: Postmodern Artists Collectives in New York City, New York, Autonomedia, 2011.