Le Corbusier 50, „Mesures de l’homme”: a retrospective under the auspices of the Modulor

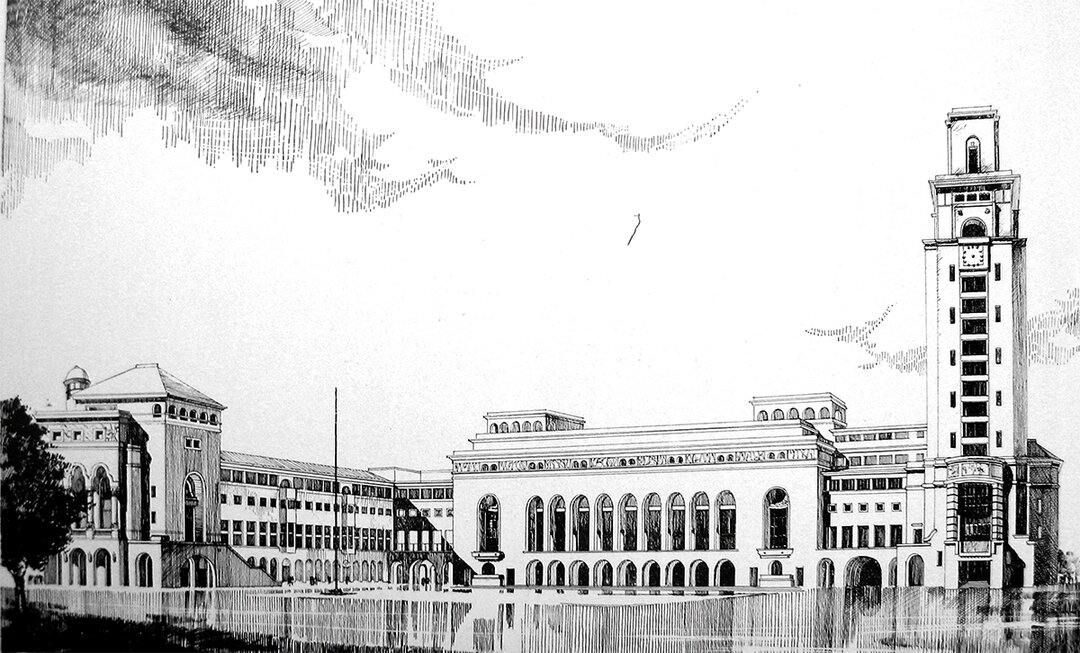

The founding act of the world's largest architectural collection took place in 1956, when the model of the Notre-Dame-du-Haut de Ronchamp Chapel, listed as a sculpture in the inventory, entered the collection of the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris. From April 29 to August 3, it is on public display - along with nearly 300 other paintings, drawings, models, publications, furniture and films - in an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou - commemorating the 50th anniversary of the death of its creator, the writer, artist, architect and urban planner Le Corbusier. This major retrospective is the main event in the Le Corbusier Foundation's program for 2015, plus 28 other exhibitions and as many conferences, ceremonies and publications. A veritable "Le CorbusYear" if we are to paraphrase the phrase consecrated in Warsaw by the Centrum Architektury Foundation, which dedicated 2012 to the architect. In her article in the magazine "Secolul 21"¹, Mariana Celac uses the term to refer to something that has already become a phenomenon: the years of its anniversaries are always marked by a profusion of events. As early as 1987, on the centenary of his birth, a first wave of exhibitions took place across Western Europe, Brazil and the United States. The Pompidou Center hosted a retrospective exhibition entitled "L'aventure Le Corbusier, 1887-1965", curated by François Burkhardt, director of the Center for Industrial Creation, together with historian and architect Bruno Reichlin, and with Vittorio Gregotti as scenographer. The second wave began in 2011, a century after the architect's initiatory journey to south-eastern Europe, and culminated this year, also in Paris. This time Frédéric Migayrou and Olivier Cinqualbre are presenting Le Corbusier to the French capital.

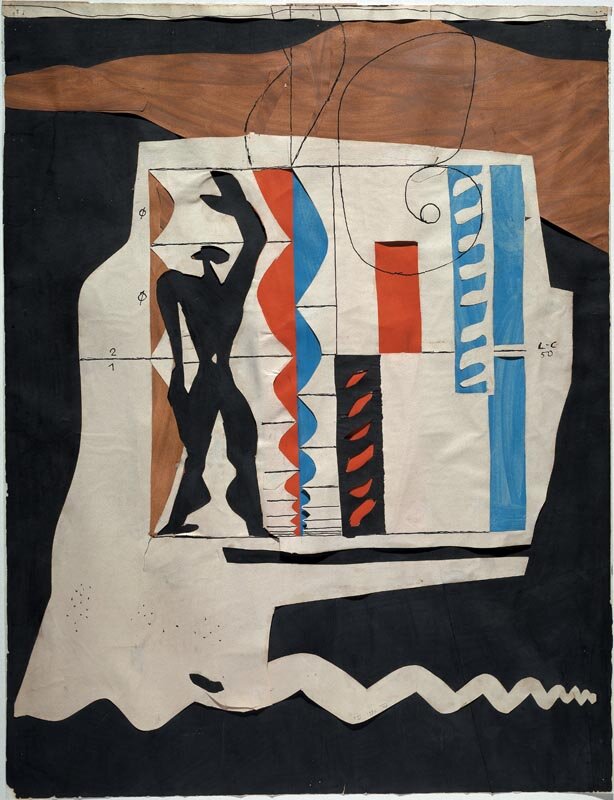

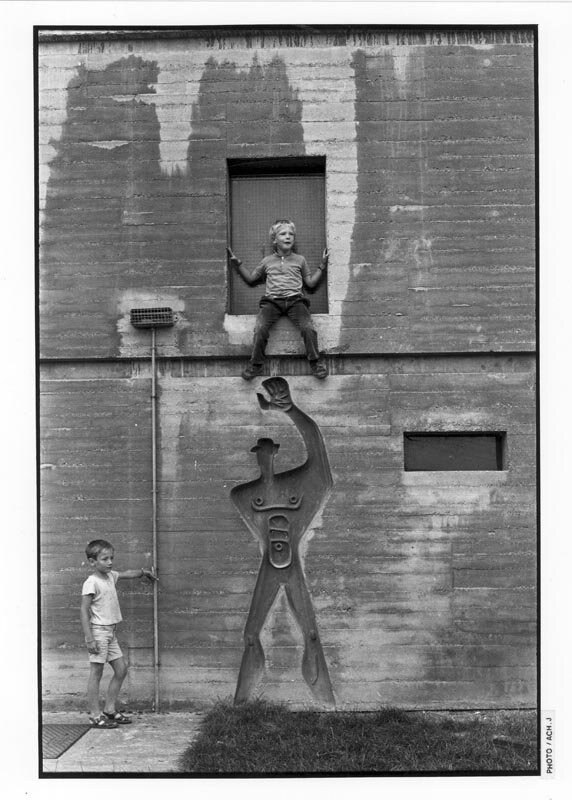

Unlike the 1987 edition, this exhibition is not a complete monograph. Entitled "Mesures de l'homme" (The Measures of Man), it investigates the architectural conception of a considerable but not exhaustive part of Le Corbusier's work through the prism of the Modulor, the famous 1.83-metre-high silhouette of the human body that has left its mark on generations of modern architects. At the Triennale in Milan in 1951, Le Corbusier presented the Modulor as a simple tool for linear and optical measurements, comparing it to sheet music² and giving it the same qualities of improving human life as aviation³. But despite this oversimplification, the curators of the exhibition are trying to reveal that it is much more than just an abstract normative metric. The phrase comes from a contraction of the terms "modulus" and "golden section"(section d'or), emphasizing the direct reference to ancient architecture, in particular the Parthenon, which the architect had visited in 1911 during his trip to the Orient. This unit, developed in direct proportion to the measurements of the human body, reveals to Le Corbusier how "architecture is perceived as a volume mathematized according to the laws of physiological harmony"4. The influence of the five months he spent in Peter Behrens' studio between 1910-1911, where he was exposed to the "Lebensreform" (life reform) movement in search of harmony, based on the psycho-physical theories of the philosopher Gustav Fechner and the psychologist Wilhelm Wundt, is also felt. With the Modulor, Le Corbusier formalizes a modern "scientific aesthetic", a system of proportions that allows the harmonious organization of all spatial constructions based on the perception of the human body.

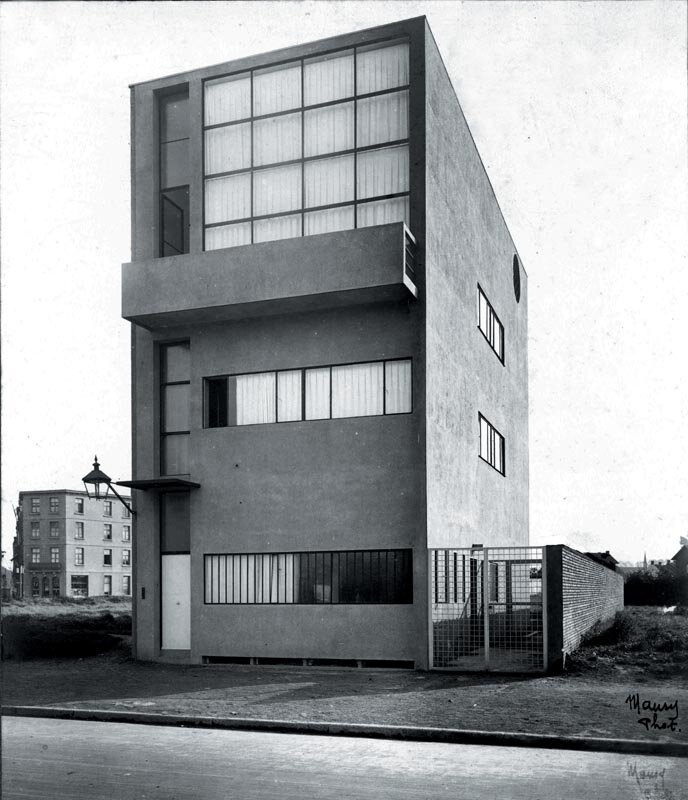

Nearly 50 drawings and objects in the exhibition are devoted exclusively to the Modulor, and the scenography also takes up the proportions prescribed by the Modulor. The rest of the exhibition traces the stages of the research that preceded this concept, with particular emphasis on the routes used in the design of individual houses and artists' studios in the 20s and 30s. In these projects one can already glimpse the search for a different way of living, a search that would later crystallize in his great collective housing projects, such as the Unité d'habitation in Marseille. At the same time, a large number of works of fine art, often devalued in comparison with Le Corbusier's architectural production, are also presented. The public is thus able to follow a broad artistic development over half a century: from the decorative motifs sketched in Germany in the first decade of the millennium, to the geometric paintings reflecting the purist theories developed with Amédée Ozenfant, to the figurative period of the 1930s, when the female body was the main subject of his work, leading to the "acoustic" years a decade later. Without this overview, the organic forms of the Notre-Dame-du-Haut Chapel in Ronchamp are hard to miss for an architect with a reputed affinity for machinism and mass production. The ensemble is complemented by a wealth of documentary evidence of his prolific career as a theoretician, as well as a large number of furniture prototypes.

The proposed itinerary concludes with a synthesis of Le Corbusier's thinking on minimal and minimal space developed around the physiology of the body: the 16 square meter cottage he built in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin (1949) on a cliff on the seafront. In the wooden "living cell"(Cabanon), the architect was almost nude, like the snapshot at the exit of the exhibition, portraying Le Corbusier painting a mural fresco at Jean Badovici 's villa5 in Vézelay (1936). A short distance away, on the morning of August 27, 1965, he drowned in the Mediterranean.

Despite three years of research and countless rare or premiere pieces, the exhibition was not without controversy. In the run-up to its opening, a media offensive was launched following the publication of three books almost simultaneously with the exhibition, which characterized Le Corbusier as a collaborator and supporter of the Vichy government, a fascist, a Nazi and an anti-Semite. They are the works of François Chaslin6, "Un Corbusier" (12 March 2015); Marc Perelman7, "Le Corbusier: Une froide vision du monde" (28 March 2015); Xavier de Jarcy8, "Le Corbusier, un fascisme français" (8 April 2015). In addition, the curators of the exhibition have been accused of having deliberately tried to sanitize the public's view of the figure of the emblematic architect, by avoiding the subject altogether. The reason for such a choice would have been to avoid a conflictual relationship with the Le Corbusier Foundation, a key player in the realization of this event. Indeed, the first half of the 1940s is represented in the exhibition only by the "acoustic period" room, which presents works of organic plastic art that would be translated into architecture a few years later with the construction of the Notre-Dame-du-Haut Chapel in Ronchamp (1950-1955). In response to the controversy, Frédéric Migayrou emphasized during the press conference that the real monograph on Le Corbusier at the Centre Pompidou was in 1987, when all aspects of his life were presented to the public, including his relations with the Vichy government. This time around, the exhibition has a different vocation, not attempting to be exhaustive of the architect's work, as witness the extremely brief presentation of his projects in Chandigarh. The selection of the projects included is based on their relevance to the curators' analysis of the architect's work, through the prism of psychophysical spatial perception and his roots, particularly of German origin. Thus, the political aspects of Le Corbusier's career do not fit in with the research directions assumed by the curatorial team three years ago. Moreover, the 'incriminating' documents on which the new publications are based come largely from the architect's private correspondence, which has been made public by the foundation that bears his name. Following these debates, however, the Centre Pompidou and the Le Corbusier Foundation have announced the organization in 2016 of a scientific colloquium to examine the institutional, economic, social and political history of the French architectural scene in the 1930s and during the Second World War, a subject that has not yet been the subject of a full academic analysis.

NOTES:

1 Entitled ""Et de plus, ça sentait partout les lys, obstinément..." Charles-Edouard Jeanneret in Bucharest in 1911", Mariana Celac's article is dedicated to the mentions made by Le Corbusier in his notebooks between June 16-22, 1911, during which time he visited Bucharest, Câmpina and Sinaia as part of his trip to the Orient. "Secolul 21, no. 1-6, 2014, p. 280-297.

2 The parallels drawn by Le Corbusier between architecture and music most likely originated in the influence of his brother, Albert Jeanneret, a violinist and composer, a disciple of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze at Hellerau from 1909 until the beginning of the First World War. During this time, he studied eurythmy, a way of approaching music that takes into account his physical perception.

3 Le Corbusier, "Conférence de Milan", Fondation Le Corbusier, Paris, 1951, p. 1. For Modulor (1943) see Le Corbusier, Le Modulor, essai sur une mesure harmonique à l'échelle humaine, applicable universellement à l'architecture et à la mécanique, Éditions de l'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, coll. Ascoral, Paris, 1949.

4 Frédéric Migayrou, 'Les yeux dans les yeux: architecture et mathesis', in Frédéric Migayrou, Olivier Cinqualbre (eds.), Le Corbusier. Mesures de l'homme, Center Pompidou, Paris, 2015, p. 20.

5 Romanian-born architect and architectural critic, editor between 1923-1932 of the important avant-garde architectural magazine L'Architecture Vivante.

6 French architect and architecture critic. Previous positions include Director of the Exhibitions Department of the IFA (Institute Français de l'Architecture) from 1980-1987, Editor-in-Chief of the magazines 'L'Architecture d'Aujourd'hui' (1987-1994) and 'Cahiers de la recherche architecturale', Deputy Editor-in-Chief of 'Techniques et Architecture'.

7 Architect, Doctor of Philosophy, researcher and lecturer at the University of Paris 10-Nanterre.

8 Journalist for Télérama.