Architects to and from Romania until 1940

text: Alexandru PANAITESCU

Photo credits: Alexandru PANAITESCU

Source of illustrations: UAR Photo Archive

During the 19th century, the complex process of the evolution of the Romanian Principalities on the Danube, then of the young state of Romania on the road to European modernity, at first at a slow pace and with many hesitations and upheavals, gradually led to the first radical transformations. From a very early period, the course towards modernity will be more and more attractive for many foreign professionals in all fields, including construction and architecture, who will come to practice in Romania, making decisive contributions to its transformation in a Western direction and distancing, albeit slowly, from the Oriental-Byzantine tradition that characterized the previous periods.

From the first decades of the 19th century, buildings with hybrid, transitional forms first appeared, in which, as a rule, a "fashionable", often simplistically interpreted, neoclassical or neo-gothic style, often with neo-classical or neo-gothic elements, more or less still traditional in their more or less traditional dress. However, local craftsmen were slowly adapting to the new tastes of the patrons, without exception members of the elite, who were eager to display their attachment to Western European values, not only in the way they dressed and behaved, the way they decorated their interiors or, above all, by their almost exclusive use of French, but also in the buildings they built to represent them. For example, around 1819, Bishop Costache Filitti asked the architect Joseph Weltz to have the Church of St. Dumitru of Oaths built "...with German craftsmanship [...] and clad with columns on the outside...".

The traditional building practices were soon lost under the influence or execution of certain works by foreign craftsmen, masons, blacksmiths, stonemasons, stucco workers, painters, bricklayers, potters, terracotta workers, etc. who came to the Principality with the first architects, all of them foreigners. They came first from Central Europe, dominated by the German tradition, then from Italy (mainly good quality craftsmen) and then, especially in the last decades of the 19th century, from France. An example of this are the families of stucco-workers from northern Italy who worked in Romania towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, to whom we owe the quality of the finishes on several buildings, particularly in Bucharest, such as the Romanian Athenaeum, the Royal Palace (in the form of the 1880-1920s), the Palace of Justice, the National Bank of Romania Palace and many other public and private buildings1, and their case is by no means unique.

In the first decades of the 19th century, until the middle of the century, the first foreign architects were mostly German, but not only, to whom we owe works of neoclassical or especially neo-Gothic architecture.

Among those solicited or/and tempted to practice architecture in the Romanian space, it is worth mentioning a Catalan, Xavier Villacrosse (circa 1790-1855), probably one of the first architects with studies in Paris to come to Romania. A personality ignored today, he worked in Wallachia, where he held a prestigious position during the reigns of the rulers, as architect of the Bucharest police (chief architect) from 1840-1848, marrying and settling here. He was the author of many works, such as the Ghica Tei Palace, designed after 1822 in neoclassical style for Grigore IV Ghica (1822-1828), the first prince of the land after the Phanariot era; the transformation of the Golescu House in Calea Victoriei into a stately palace (1837); reconstruction of the Radu Vodă Monastery (after the earthquake of 1838), with major neoclassical interventions carried out together with Joseph Weltz and Heinrich Feiser; reconstruction and consolidation of the Church of St. Gheorghe Nou after the fire of 1847, to which he added a large portico and a controversial neoclassical spire; participation with Anton Heft and others in the design and realization of the Great Theatre (completed in 1852); rebuilding in neo-Gothic style and monumental dimensions the Church of St. George. Spiridon Nou (1852-1858) in Calea Șerban-Vodă, Bucharest, the work being completed by the architect Luigi Lipizer (probably 1825-1864), a native of Dalmatia, who was active in Wallachia from 1856 to 1862.

The Swiss-born architect Johann Schlatter (1808-1865), a "monastic architect" favored by the ruler Gheorghe Bibescu (1842-1848), was also active during the same period, and in the mid-19th century he designed in a neo-Gothic style, historicist-romantic style, the partial or complete restoration of the churches and precincts of the monasteries of Dealu, Bistrița, Arnota (transformed into a royal prison), Tismana, as well as the Church of the Annunciation - Curtea Veche in Bucharest, the church of Antim Monastery and so on.a. He also completely rebuilt the Chindiei Tower in Târgoviște and designed a grandiose palace for Bibescu Vodă, located approximately in the area of the current railway station and the CF Băneasa passage, a work left unfinished after the abdication of the ruler in 1848 and whose last ruins were demolished in 1939. The neo-Gothic style, often in simplified forms, mainly used by Schlatter, as well as the neoclassical style in the case of Villacrosse, were contested in the following decades, and most of their works were subsequently transformed or destroyed2.

Also until the mid-19th century, foreign architects were responsible for the realization of other significant buildings, such as, in a very selective list, the Church of St. Dumitru de Juramânt (1819) and the Ghica-Tei Chapel (1833), both works in Bucharest by the architect Joseph Weltz; the Ghica Palace in Căciulați-Ilfov, the Suțu Palace, after 1833, arch. Conrand Schink and then in 1862, arch. Johann Veit; Iași Cathedral, 1833-1839, arch. Gustav Freywald and, 1880-1887, arch. Alexandru Orăscu. In Bucharest we also note the Theater "cel Mare" - National Theater on Calea Victoriei, completed in 1852, arch. Anton Heft and others; the Liebrecht-Filipescu House in Dionisie Lupu Street, Bucharest, after 1860, arch. Luigi Lipizer; Știrbei Palace on Calea Victoriei, circa 1835, arch. Michel Saint-Jourand or Sanjouand, with studies at the "École Nationale des Beaux-Arts" in Paris, the first French architect to practice in Wallachia, later, around 1881 the palace will be enlarged by the Austrian architect Friederich Hartmann. In Iași, in addition to several residences transformed with forms suggesting neoclassical intentions, the Sturdza Palace, known as the "palace on the walls", built at the Frumoasa Monastery, before 1819, is worth noting. Marin Kubelka.

Also until the mid-19th century, foreign architects were responsible for the realization of other significant buildings, such as, in a very selective list, the Church of St. Dumitru de Juramânt (1819) and the Ghica-Tei Chapel (1833), both works in Bucharest by the architect Joseph Weltz; the Ghica Palace in Căciulați-Ilfov, the Suțu Palace, after 1833, arch. Conrand Schink and then in 1862, arch. Johann Veit; Iași Cathedral, 1833-1839, arch. Gustav Freywald and, 1880-1887, arch. Alexandru Orăscu. In Bucharest we also note the Theater "cel Mare" - National Theater on Calea Victoriei, completed in 1852, arch. Anton Heft and others; the Liebrecht-Filipescu House in Dionisie Lupu Street, Bucharest, after 1860, arch. Luigi Lipizer; Știrbei Palace on Calea Victoriei, circa 1835, arch. Michel Saint-Jourand or Sanjouand, with studies at the "École Nationale des Beaux-Arts" in Paris, the first French architect to practice in Wallachia, later, around 1881 the palace will be enlarged by the Austrian architect Friederich Hartmann. In Iași, in addition to several residences transformed with forms suggesting neoclassical intentions, the Sturdza Palace, known as the "palace on the walls", built at the Frumoasa Monastery, before 1819, is worth noting. Marin Kubelka.

In addition to these, there are countless other larger or rather small works, exclusively the work of foreign architects, not always well trained, which nevertheless sought to change, even if only in a punctual way, the urban ambience, in a European sense, of Romanian towns, especially Bucharest and Iasi.

Also worth mentioning for the middle of the 19th century is a work of great monumentality, generally omitted from specialized Romanian literature3, probably because it was realized in a territory which then, as now, was not within the natural Romanian borders. It is the Metropolitan Palace in Chernivtsi, Bukovina (1864-1882), designed by the Czech architect Josef Hlávka (1831-1908), built with brick facades, with a form that, in a historicist approach, combines refined neo-Moorish, neo-Byzantine and medieval Moldavian architecture elements in a synthesis of great value.

In the last two decades of the 19th century, after Romania's proclamation as a kingdom in 1881 and in the first decade and a half of the 20th century, a series of large administrative buildings and cultural institutions, as well as sumptuous private residences in Bucharest, Iasi and gradually also in other cities of the smaller Romanian states, became landmarks of the European evolution. In a very selective and inevitably incomplete list, a few monumental buildings erected in Bucharest are worth mentioning, such as the eclectic ones, most of them of the French school: the National Bank Palace, on Lipscani str., 1883-1885, arch. Cassien Bernard and Albert Galleron; CEC Palace, 1896-1900, arch. Paul Gottereau; Palace of Justice, 1890-1895, arch. Albert Ballu, interior decorations arch. Ion Mincu; the Royal Palace, 1882-1885 (transforming and extending the Dinicu Golescu House dating from around 1815) and the main wing of the Cotroceni Palace, circa 1893, arch. Paul Gottereau; Palace of the Ministry of Agriculture, 1896, arch. Louis Blanc, etc. A large-scale work expressing the will and tastes of King Charles I is the Peles Castle in Sinaia, initially in the style of the German Renaissance, 1875-1883, designed by the German architects Wilhelm von Doderer and Johannes Schulz, then enlarged and redecorated between 1896-1914 by the Czech architect Karel Zdeněk Líman.

These large-scale works were carried out with the contribution of foreign architects, mainly from France and Italy, but also from Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who worked in Romania for short or long periods, such as Paul Gottereau (1843-1924), Albert Ballu (1849-1930), Giulio Magni (1859-1930), Albert Galleron (1846-1930), Cassien Bernard (1848-1926), Karel Zdeněk Líman (1855-1929). Others also settled here, such as Gaetano Burelli (1820-1896), André Lecomte du Noüy (1844-1914), Louis Blanc (1860-1903), Daniel Renard (1871-after 1935) and others.

After the first pioneering phase, full of hesitations and hesitations until the middle of the 19th century, many of the aforementioned architects, active towards the end of the century, can be considered, thanks to their works of great value, to have laid the foundations for the crystallization of architecture in modern Romania and its increasingly firm connection with that of the West, expressed mainly in eclectic forms corresponding to the trends of the time.

In Bucovina around 1900, the Austrian architect Karl Adolf Romstorfer (1854-1917) is regarded as a pioneer in the field of research and restoration on a scientific basis of architectural monuments in this area, including: the Suceava Fortress (1897-1903); the Șcheia Fortress; the Mirăuți Church (1898-1903); the Putna Monastery Church (1901-1902); the Church of St.. Apostles Peter and Paul in Solca (1901-1902); St. George's Church and the bell-tower of St. John the New Monastery in Suceava (1904-1910) and so on.

In another Romanian area, Transylvania, which was also under Austro-Hungarian authority until 1918, architects from all parts of the empire, mainly Hungarians, but also Czechs and Austrians, were to be found, who, through their numerous representative buildings, helped to give the region a specific character, emphasizing its multicultural and multiethnic nature. In a very brief mention we mention only the Town Hall, the Greek-Catholic Bishop's Palace and the Apollo Palace, works by arch. Rimanóczy Kálmán-fiul, the Poinar and Kolozsvári Palaces, arch. Ferenc Sztarill, all from Oradea; the Black Eagle Complex, also from Oradea; the Administrative Palace and the Palace of Culture in Târgu Mureș; as well as the Theater in Deva, works by the architects Jakab Dezső and Marcell Komor. The Neptun Palace, architect. László Székely, from Timișoara, or the Reformed Church "with the rooster", arch. Kós Károly from Cluj and many others. Works by Hungarian architects, most of them are also examples of the Hungarian or Austrian 1900 Style, which was also practiced in Transylvania in the early 20th century.

During the same period it is also worth noting the intense activity of the architectural office led by the Austrian Ferdinand Fellner jr. and the German Hermann Gottlieb Helmer, specialized in the design of concert halls. Between 1870-1913, they built 42 theaters, primarily in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Vienna, Budapest, Szeged, Fiume-Rijeka, Karlovy Vary, Poszony, Prague, Zagreb, etc.).In Romania, they built theaters in Timișoara (the main facade was transformed in neo-Romanesque style in the 1930s by the architect. Duiliu Marcu), Cluj, Oradea, Cernăuți, as well as the one in Iași, Romania. From a stylistic point of view, the two architects skillfully amalgamated elements of the Italian, German, French and Dutch renaissance, in a well mastered synthesis with baroque and rococo elements, in the last period and in specific interpretations of the 19004 style.

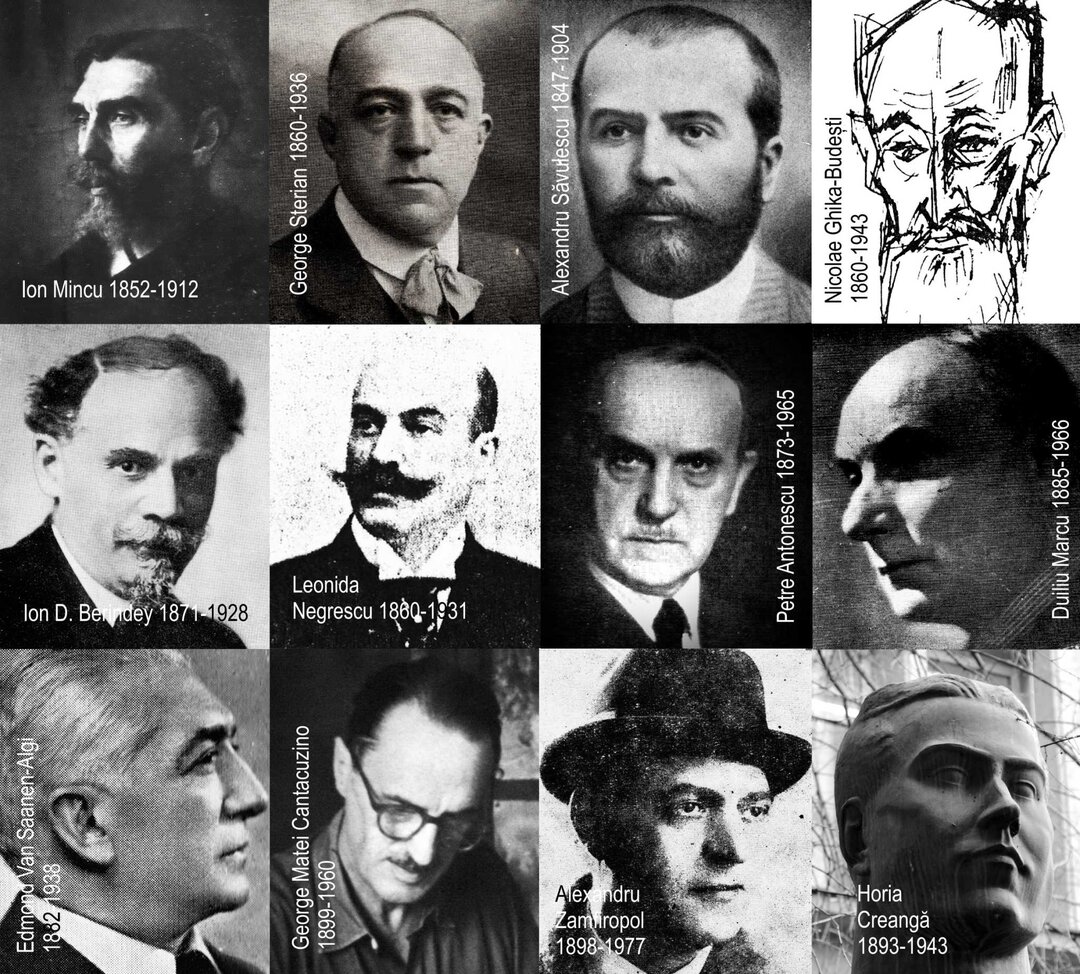

In Romania, in the borders of the last decades of the 19th century, a new, indigenous generation, made up of Romanians educated in Paris, graduates of the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, was to assert itself strongly. Here are just a few of them: Ion Mincu (1852-1912), Ștefan Ciocârlan (1856-1937), Leonida Negrescu (1860-1931),on D. Berindey (1871-1928), Jean George Pompilian (1872-1938), Toma Dobrescu (1862-1934), Eracle Lăzărescu (1868-1937), Alexandru Săvulescu (1847-1904), Dimitrie Maimarolu (1859-1926), George Sterian (1860-1936), Ion N. Socolescu (1856-1924), Ștefan Burcuș (1871-1928) and others.

For the professional establishment of the first generation of Romanian architects, after some unsuccessful attempts, on February 26, 1891 the Romanian Architects Society - SAR was founded, followed in 1892 by the establishment of the School of Architecture, first as a private institution belonging to SAR, from 1897/1904 taken over by the state; followed in 1906 by the first issue of the magazine Arhitectura. Their work, which over time had to overcome numerous obstacles, has continued to this day, proving to be enduring.

Nicolae Ghika-Budești (1869-1943), Petre Antonescu (1873-1965), Nicolae Nenciulescu (1879-1973) were also part of the following series of Romanian architects trained at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts, Paul Smărăndescu (1881-1945), Edmond van Saanen-Algi (1882-1938), Roger Bolomey (1883-1947), Duiliu Marcu (1885-1966), Constantin Pomponiu (1887-1945), followed by Horia Teodoru (1894-1976), George Matei Cantacuzino (1899-1960), Ion Al. Davidescu (1890-1980), Alexandru Zamfiropol (1898-1977), Horia Creangă (1892-1943), Robert Mihăescu (1895-1970), Theonic Săvulescu (1907-1976) and so on.

Finally, it should be pointed out that many of the Romanian architects trained abroad were responsible for the realization of numerous edifices and buildings that were functionally diverse, demonstrating great stylistic versatility, especially in the inter-war period. They were thus able to practice with such ease both in neoclassical-eclectic forms and later in the national spirit that they brilliantly composed the neo-Romanesque style. From the mid-1920s many opted for Art Deco or/and modern-cubist, but also classically modernized expressions, succeeding in a few decades to redefine the Romanian built environment architecturally-urbanistically. The limited space of an article, forcing to an excessive and inevitably too subjective selection, makes us avoid exemplifying some valuable works realized by them, especially since they are generally well-known.

Also, some of the architects trained abroad were also professors at the Higher School of Architecture in Bucharest, training highly respected professionals whose qualities were confirmed during the interwar period. With regard to the work of the School of Architecture, it should be noted that, due to the fact that most of its staff were trained mainly in Paris, even though it promoted architecture in a national, "neo-Romanian" style from the outset, it was dominated by the "Beaux-Arts" spirit. In this sense we appreciate, like the architect Radu Patrulius: "... the immense service of the Beaux-Arts school in stimulating skill in: imagination, symbolism, clarity, reason of function, interesting flattery of spaces; hierarchy and order, decoration; as well as other skills that are not lacking in the evolution of our profession" to which was added his contribution to the shaping of public taste "... through Vitruvian, Palladian exercises or through the syntax of national monuments..."5. Paraphrasing a slogan from the early 1950s, it is not an exaggeration to consider that the School of Architecture in Bucharest was initially "Beaux-Arts-ist in substance and neo-Romanian in form". This characteristic, which was to mark, more or less, the Romanian architectural education, was to be felt until the 1960s. A much smaller number of Romanian architects were also trained during the same period at schools in Berlin, Rome, Milan, Munich, Vienna, Milan, Vienna and so on, while others benefited from training periods at the Accademia di Romania, which was set up in Rome in the 1930s on the initiative of Nicolae Iorga.

Also, some of the architects trained abroad were also professors at the Higher School of Architecture in Bucharest, training highly respected professionals whose qualities were confirmed during the interwar period. With regard to the work of the School of Architecture, it should be noted that, due to the fact that most of its staff were trained mainly in Paris, even though it promoted architecture in a national, "neo-Romanian" style from the outset, it was dominated by the "Beaux-Arts" spirit. In this sense we appreciate, like the architect Radu Patrulius: "... the immense service of the Beaux-Arts school in stimulating skill in: imagination, symbolism, clarity, reason of function, interesting flattery of spaces; hierarchy and order, decoration; as well as other skills that are not lacking in the evolution of our profession" to which was added his contribution to the shaping of public taste "... through Vitruvian, Palladian exercises or through the syntax of national monuments..."5. Paraphrasing a slogan from the early 1950s, it is not an exaggeration to consider that the School of Architecture in Bucharest was initially "Beaux-Arts-ist in substance and neo-Romanian in form". This characteristic, which was to mark, more or less, the Romanian architectural education, was to be felt until the 1960s. A much smaller number of Romanian architects were also trained during the same period at schools in Berlin, Rome, Milan, Munich, Vienna, Milan, Vienna and so on, while others benefited from training periods at the Accademia di Romania, which was set up in Rome in the 1930s on the initiative of Nicolae Iorga.

In the 1920s and 1930s, and even before the First World War, in addition to their studies, architects' trips for research or, as a rule, unrestricted holidays abroad on their own, especially to France, Italy, etc., or for treatments in spas and other resorts, were a matter of course for their professional and social practice and prestige.

In the inter-war period, however, the flow of architects that we consider formative for Romanian architecture will practically come to an end, mainly made up of foreigners who came to practice, and sometimes to live, in Romania or Romanians who returned home after studying architecture abroad.

It should also be noted that, especially with the establishment of the SAR, there has been a gradual tendency to favor exclusively the right of practice of Romanian architects, by questioning, then limiting and even excluding the activity of foreign architects. A clear signal in this respect can be seen in the dispute around 1900 concerning the restoration work of the French architect André Lecomte du Noüy, a close friend of King Charles I, who excessively applied the restoration principles of the French architect Eugéne Viollet-le-Duc, in some cases demolishing monuments of undeniable value in order to rebuild them in forms considered stylistically ideal.

A few years later, at the SAR Congress of 1916, it was proposed to prohibit the entrusting of public works to foreign architects and to make it compulsory for all state architectural works to be awarded only through a national public competition in which, in addition to Romanian architects, foreign architects could also participate, provided they had been established in the country for at least five years.

During the inter-war period, the right of foreign architects to practice was restricted until it was banned, with rare exceptions, such as the design of the Telephones Palace, realized in association between the architect Edmond van Saanen-Algi and the American architects Louis Weeks and Walter Froy, or the German-Jewish architect Rudolf Fränkel (1901-1974), one of the architects of the Scala and Adriatica blocks on Calea Victoriei, etc, active in Romania between 1933-1937, a refugee in Great Britain, and settled in the United States after the war.

In the insecure conditions of the late 1930s and early 1940s, the conditions for practising the profession of architect were gradually tightened, including the adoption in October 1941 of a new law organizing the Romanian College of Architects - CAR, which, among other things, made it compulsory to present a certificate of nationality and ethnic origin when enrolling in the College.

After a few years, these situations were far outweighed in severity by other measures imposed by the new communist regime, which had been in place since March 1945 with the support of the Soviet occupiers. There followed not only an overthrow in all aspects of the architects' practice framework, but also a limitation, to the point of exclusion, of the links with the professional environment in the West and an exclusive orientation towards the Soviet one, fracturing for several decades the natural evolution of Romanian society and culture, and implicitly of architecture.

NOTES

1.See the study La via del marmo artificiale da Rima a Bucarest e in Romania tra otto e novecento (The Artificial Marble Road from Rima to Bucharest and other Romanian cities during the period of Carol I), published by the Zeisciu Cultural Center for Studies, Italy, 2010.

2.Including for a presentation of the work of several foreign architects of the first half of the 19th century in Walla Wallachia see Horia Moldovan, Johann Schlatter, western culture and Romanian architecture (1831-1866), Simetria Publishing House, Bucharest, 2013

3. An exception is the work Cernăuți - arhitectură europeană, arhitectură românească (1860-1940) by Octavian Carabela, Mihaela Criticos, Aurelia Carpov, Irina Korotun, Dragoș Olaru, Editura Simetria, București, 2018, p. 44-49.

4. Information and illustrations for the architects active in Transylvania during the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the Dictionary of Transylvanian Architects during the Austro-Hungarian Dualist Period, by Varga Atilla and Gabriela Rus, Argonaut Publishing House, Cluj-Napoca, 2017.

5. From the article "Roger H. Bolomey", arh. Radu Patrulius, Arhitectura magazine no. 1/1982, p. 49.