Clutch down

© Mihnea Mihalache-Fiastru

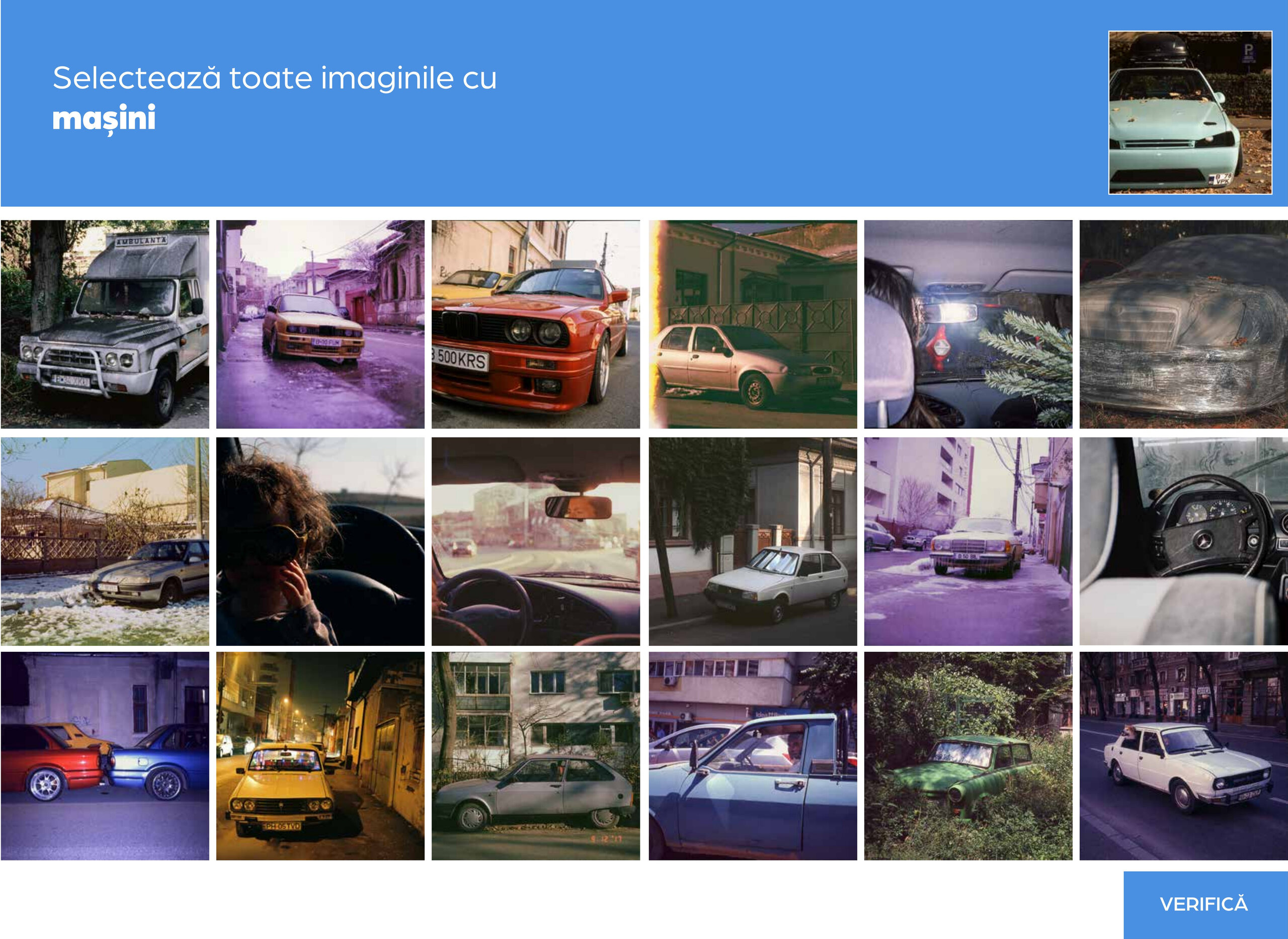

My grandfather used to take me out to the car to help him with the scent pads under the rubber floor mats of his Dacia 1100. It had license plate number 1-B-6757, gray, rear-wheel drive, front trunk, and an upholstery of a black and green fabric, which I didn't like at the time, but now it's like you'd get a car just for a good upholstery like that.

Clutch down, first gear

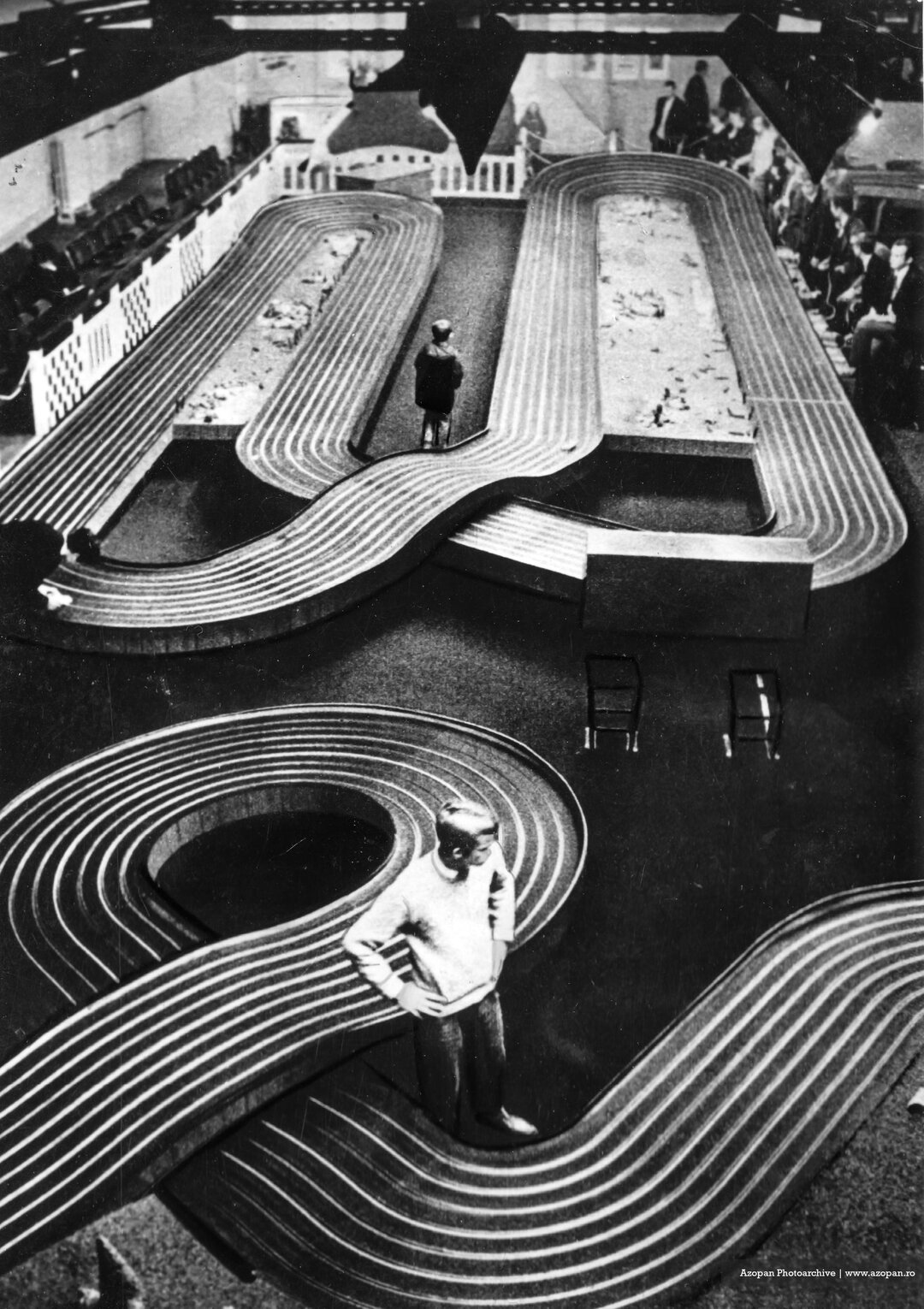

Before Wunder Baum, essences, and other car smells, in the '80s car odorizers were these multi-layered paper plates that you impregnated with lavender and put under the rubber floor mats, where they stayed until the smell evaporated completely. Then they'd put perfume on them again and so on. I think when I was about 5 years old, that was the first time I ever helped with the car. If I think about it, it was the only time since then. It happened in the typical villas built in 1960-1961, in the area of Intrarea Văcărești - Aleea Zânelor - Strada Sibiel, P+2 or P+3 block-villas, with gardens in front and back and the space between them laid out with gravel for parking, benches for the residents and many lime trees whose strong smell woke you up and put you to sleep every June. I still know all the cars in that parking lot, between Villa 2 and Villa 3, the one where my grandparents lived: My grandfather's Dacia 1100, Ivanciovici's neighbor's Dacia 1100, the yellow Lada 1200 of the neighbor on the first floor, on staircase B, the yellow Dacia 1300 of Gulimănescu, my friend Vali's father, my friend Vali's friend's father, the two Oltcituri of the neighbor on the ground floor, the two Skoda 120s, one white and one green, of Ianovschi and the white Dacia 1300 of Mr. Focșa. That was all. My grandfather came to Bucharest at the age of 14, in '43, from Berbești, Vâlcea, and started working as an apprentice car mechanic. He lived in a small courtyard in Cotroceni, on Medic Severin Street, and the older people there still remember him and his family for how poor they were compared to the people in the area. The Fiastru family. Beyond the difficult material situation he came from, he liked cars, and after 1950 he specialized and became one of the managers of the Danubiana tire company. Although he could see his work in the office, he still liked to spend his time among car parts and objects. In the evenings, when he came home and changed, the skin on his feet would be stained black with smoke from the tire production line. Eventually, because of the work environment, he also became ill with various cardiovascular diseases after the age of 60. In 1970 he had an accident on a snow-clearing operation in Ilfov, when at 5 in the morning, on the way to the objective, the ARO car in which he was with 4 colleagues overturned on the ice. His knee was shattered and he was then considered inoperable.

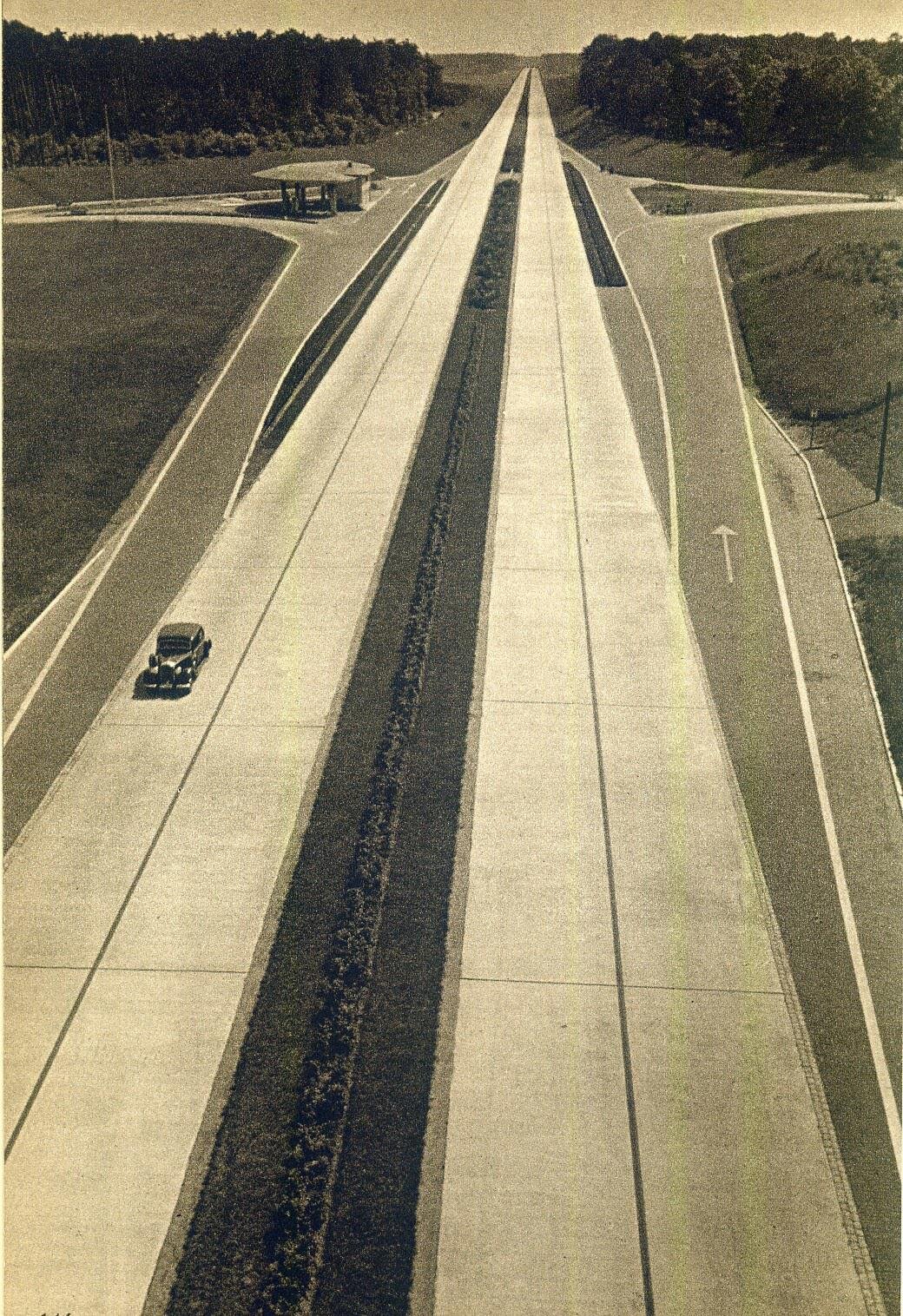

But even so, a year later, he took his Dacia 1100 with which we went on all my grandparents' vacations in the 80s, to Eforie Nord, Herculane, Vatra Dornei or to the countryside, to Berbești, where he was from. My grandfather wouldn't have done anything illegal, at least not in any way, at least not any motoring. In the 1980s, when only Sundays were a day off, cars were allowed to circulate on the basis of a decree which stipulated that on one Sunday only cars with an even number on the last digit of the license plate were allowed to circulate, and on the following Sunday only those with an odd number on the last digit. There were exceptions: protocol cars, diplomatic cars and cars with three-digit license plates indicating an owner with a position of power or influence in society, which were not stopped by the militiamen. In common parlance we used to talk about cars with 'with husband' or 'without husband' license plates. I was born on a Sunday, October 10, 1982, when it was the turn of cars with husbands to have the right to drive, so my grandfather couldn't take my mother to the hospital and my father had neither a license nor a car, and my grandfather didn't risk taking the Dacia 1100 out in traffic, so he went on foot to the maternity hospital, and my parents arrived in the yellow Dacia 1300 of Gulimănescu, whose son, Vali, was 1 year old at the time and who I played with all my childhood, at my grandparents' until I was 10. Vali died around the age of 30, and his father, with the yellow Dacia, shortly before him. Grandfather could dismantle and build a car from scratch, unfortunately I never caught him in the mood for that, but I often heard him giving the most accurate advice to the neighbors. Towards the end of the 80's the habit of going out to the car had settled in, pensioners and men of that time gathered to repair one car or another, most people were good at fixing almost anything on a Dacia. And if they couldn't, help was just a doorbell away. Grandpa decided in '88 to give up the Dacia 1100 and swap it for a Dacia 1310 or 1410. He put himself on the waiting list for the car and asked for the color "café au lait". In those years, cars were more garish, loud and fun colors than they are today. After a year or so of waiting, the Dacia "café au lait" color didn't appear, instead, the possibility of a Dacia 1410 in Mamaia blue color came up, which grandpa accepted. For a couple of years he was very proud of it, drove it around the countryside and built in the trunk, as was a sort of fashion at the time among some Dacia owners, a plywood cupboard with sliding doors in which to keep tools, whatever that meant or what those tools were. It was his second and last car, he died in 1998, incapacitated and frustrated that he could no longer drive. His car went to a nephew in Berbești.

Clutch down, second gear

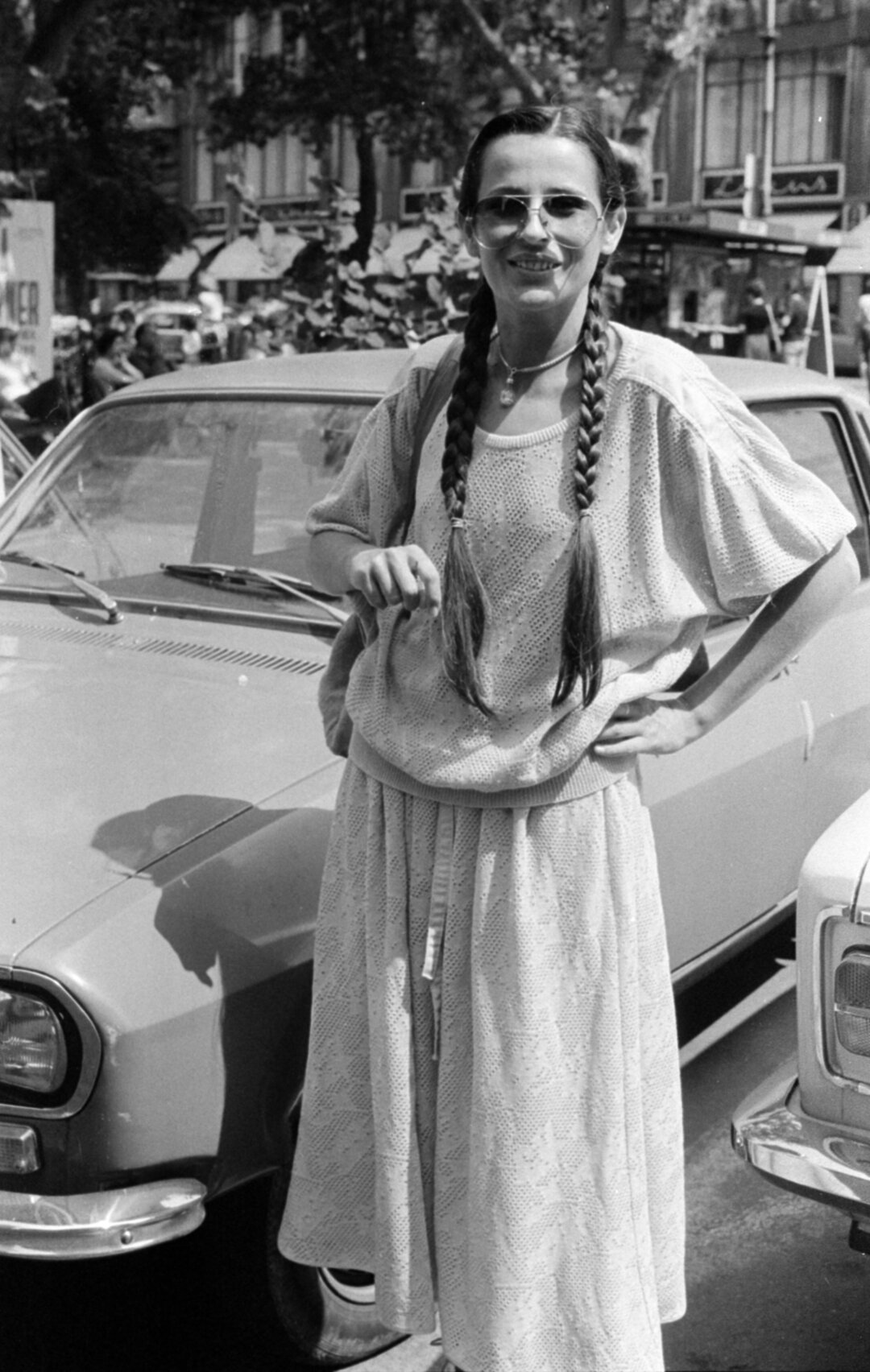

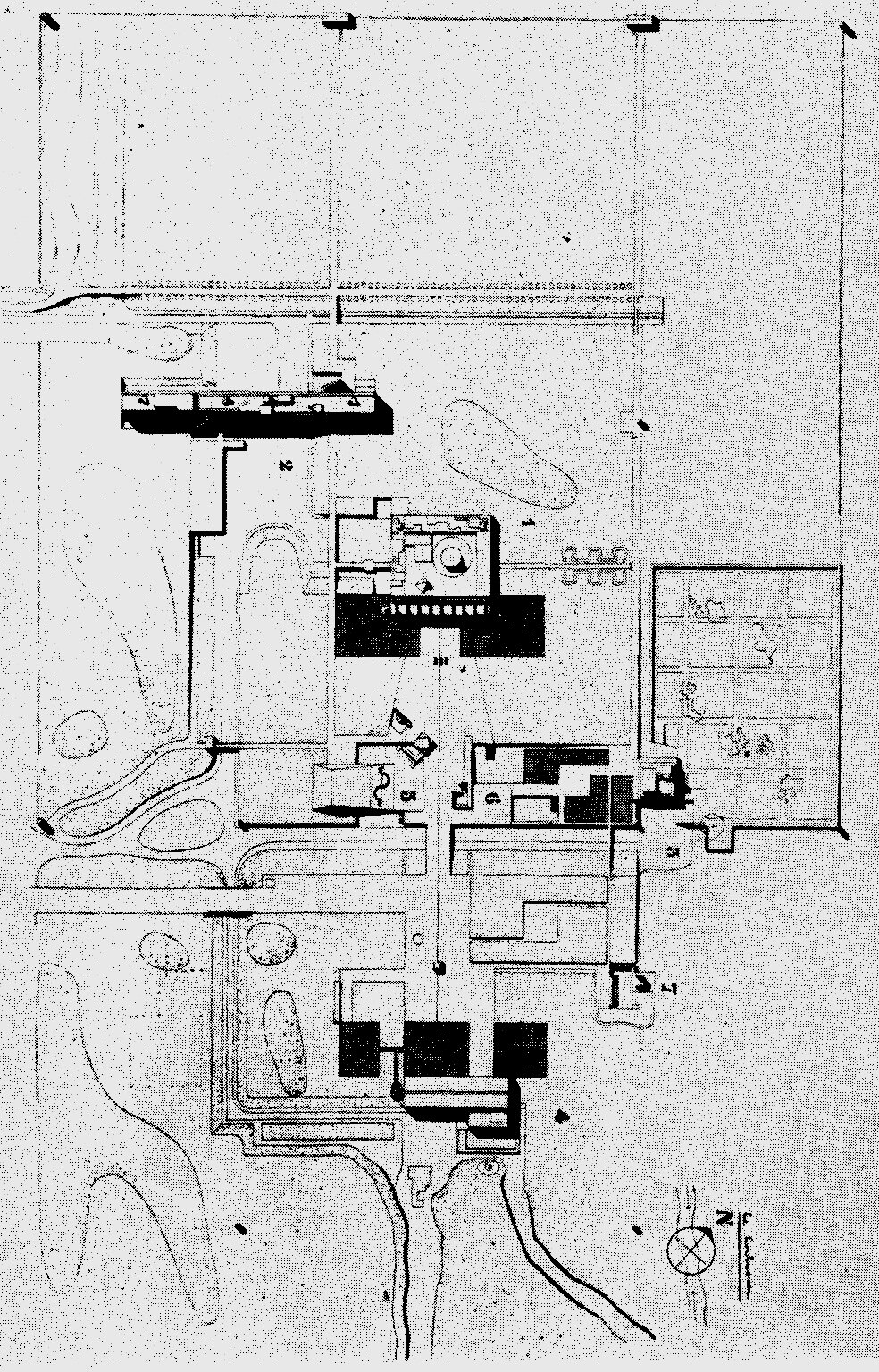

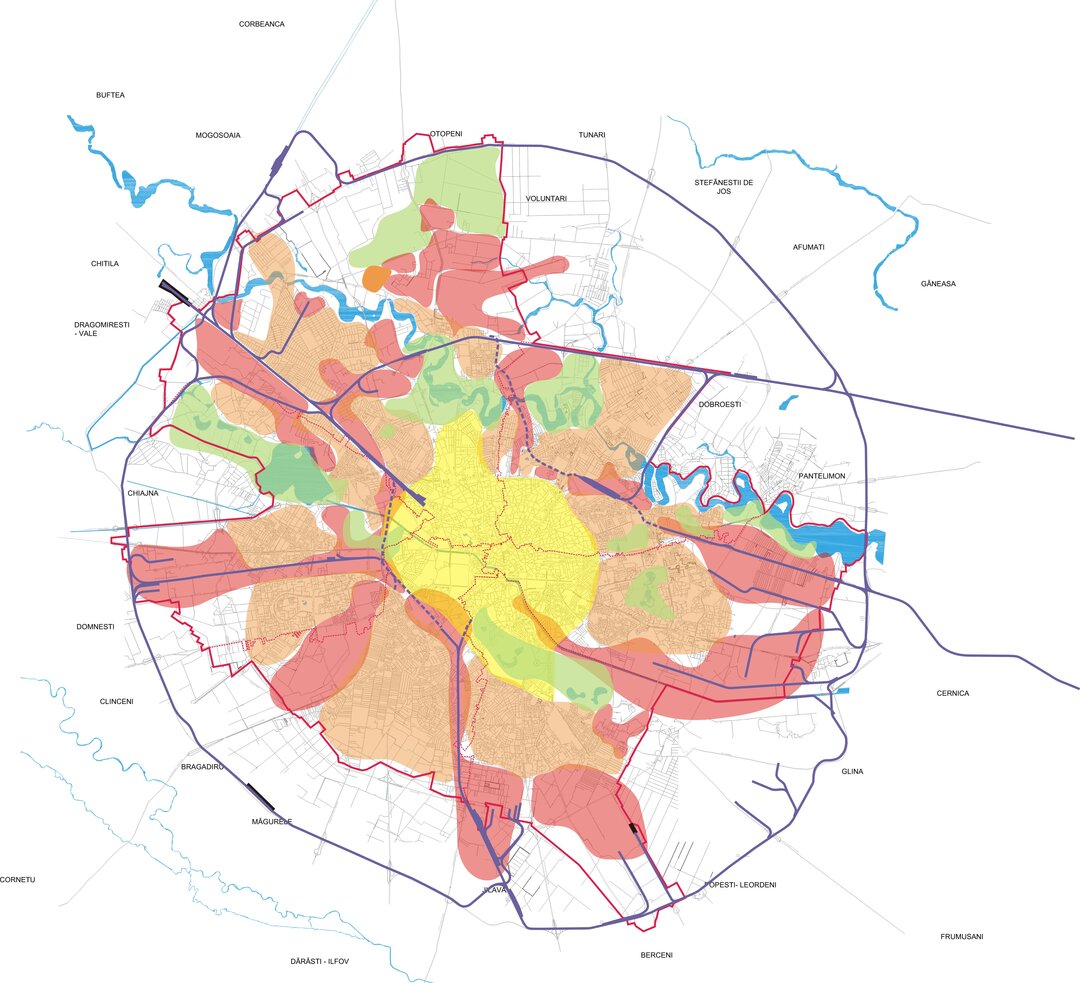

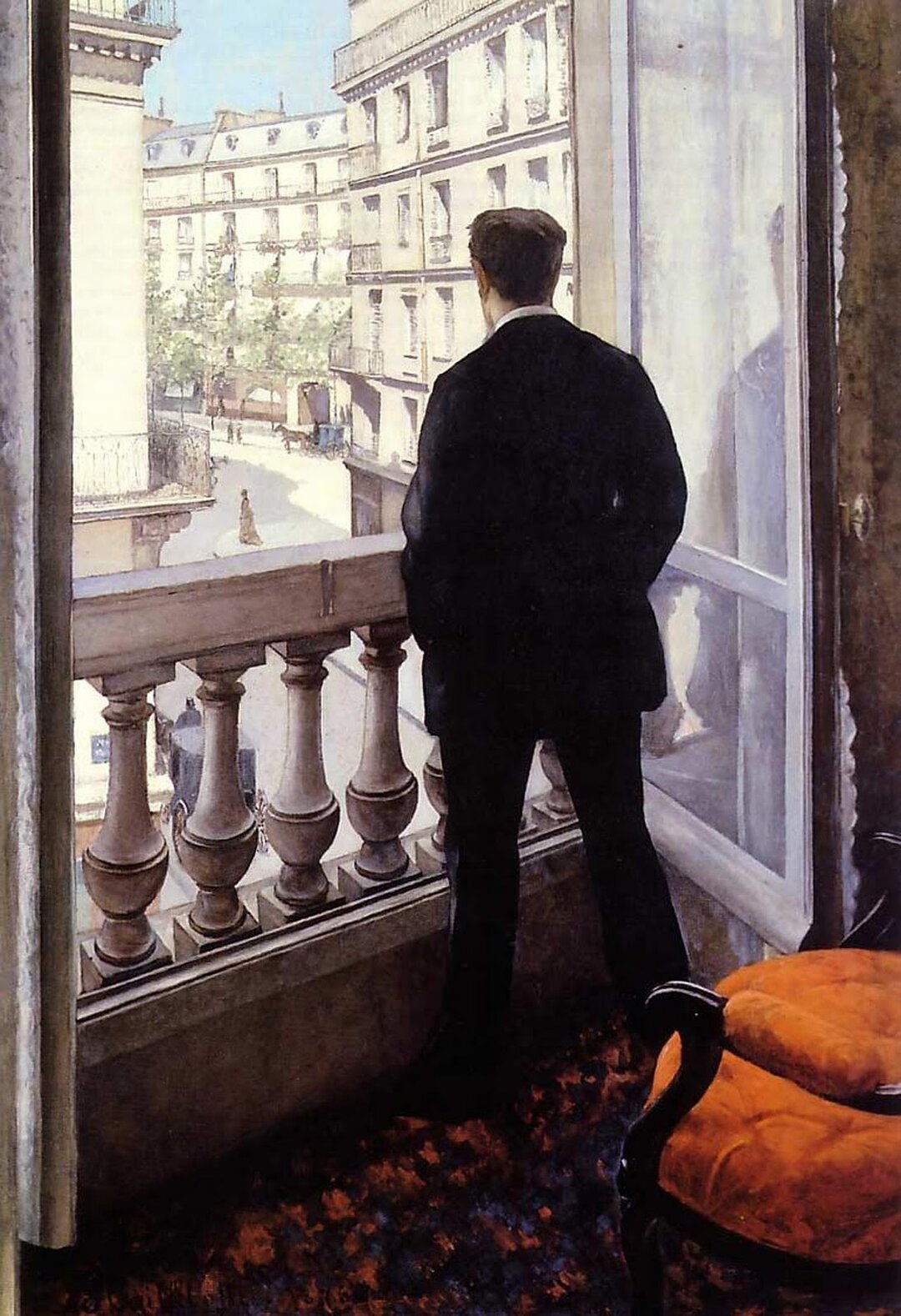

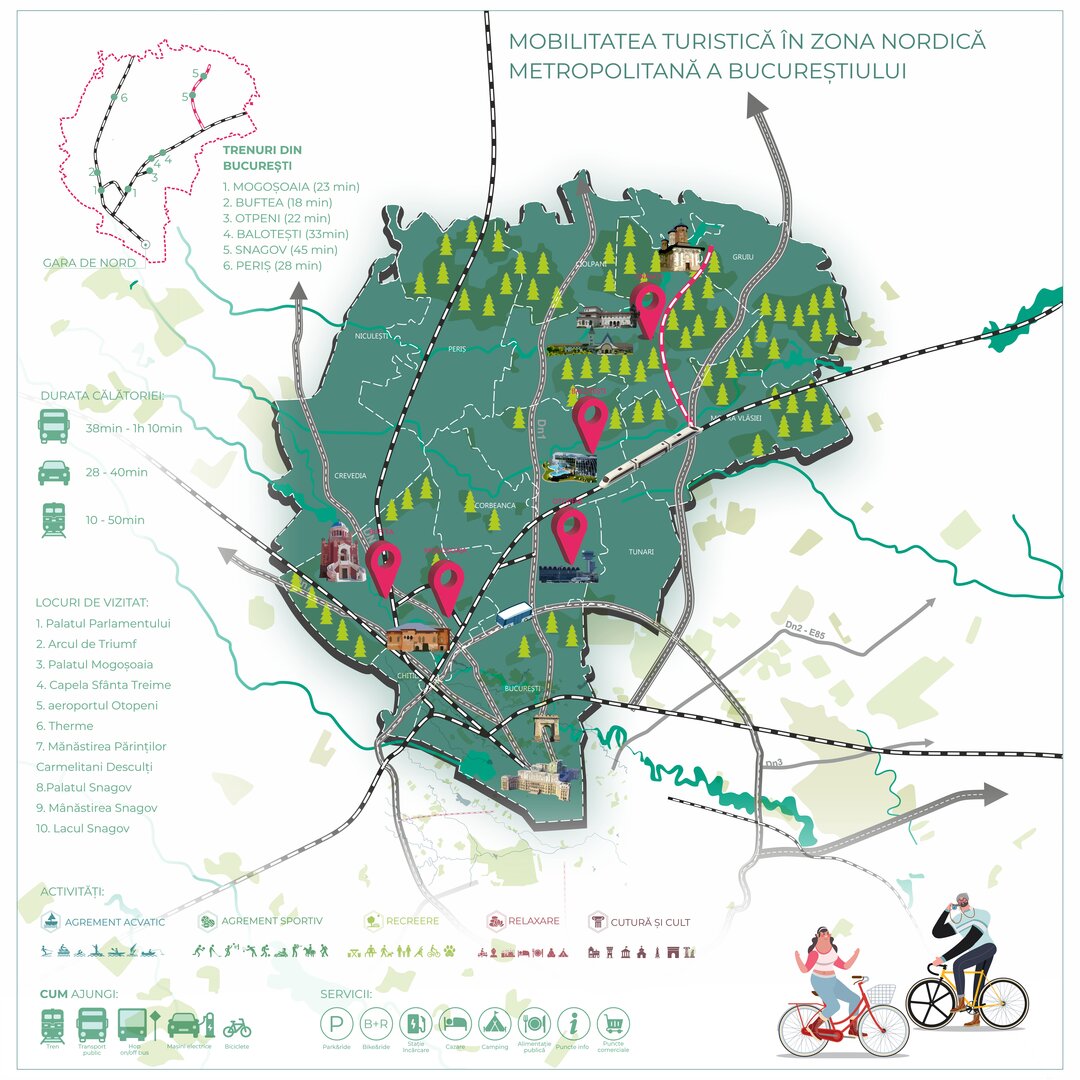

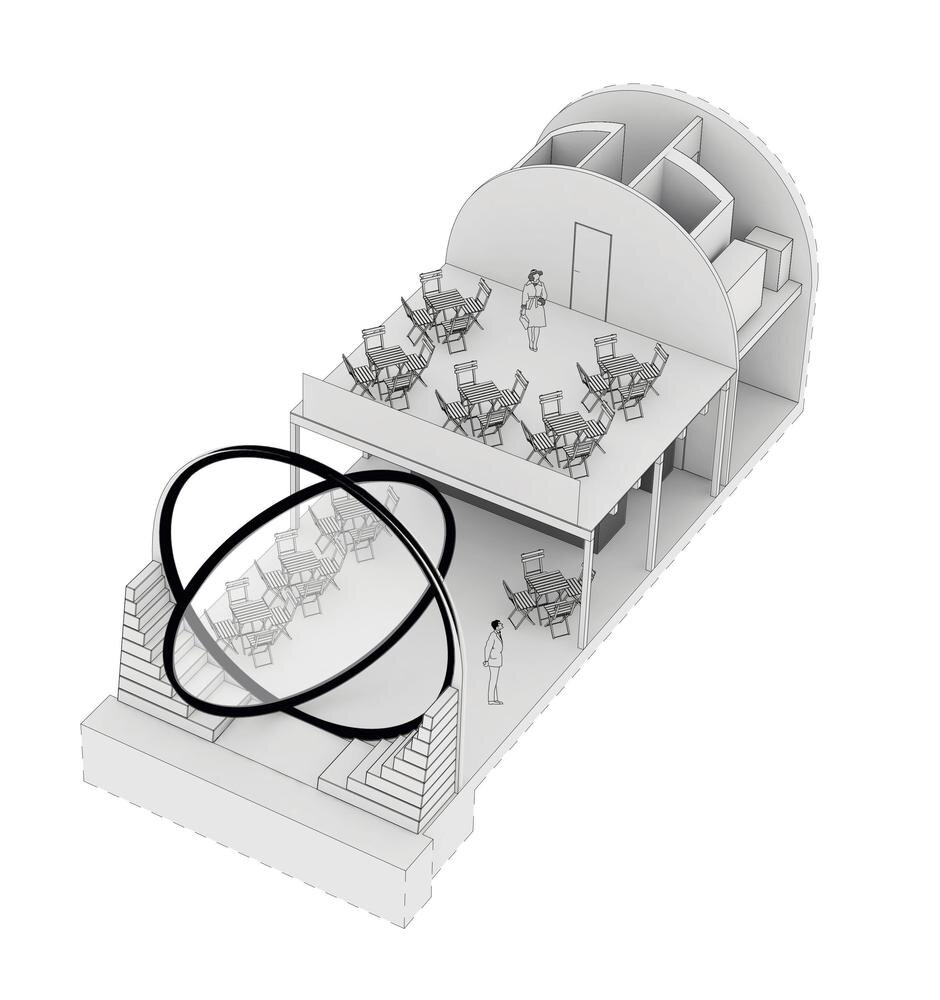

As early as the spring of 1990, all kinds of cars of different makes began to appear, of which I had never seen before, the same ones we know now, but seemingly more of them and more variety. It was easier to experiment, cars considered luxury or expensive, were no longer just for people in state positions, they were now available to anyone who knew their way around in this environment where these second-hand cars, generally from the West, were being driven. I lived in an area in Bucharest where many people were involved in selling and buying cars and I know that it was not an occupation with negative content or connotation, as people imagined, all the Mercedes, BMWs, Volvos, Fords, Renaults and so on were just objects of the new world that we wanted to be part of and experience as best we could. Some were into jeans, some into sweets, some into Lego and toys, some into dog breeds, some into alcohol and tobacco and some into cars. They were all objects that basically had the same basis (fascination, reclamation) and the same purpose (integration). The people who brought, bought and sold cars were nothing more than agents of the new culture, who had a well marked role in our city's recent history. I saw a lot of cars in those days and collected Turbo gumball surprises, I liked to observe them, I still do, I tried to collect Matchbox metal models, Corgi Juniors and Majorettes. However, I always felt a distance between myself and the whole motoring thing, something that would never develop into a real passion. My mother had a granddaughter who was a ballerina at the Opera who, just after December 1989, bought a Citroen BX which to this day sticks in my memory as one of the coolest cars I've ever been in. From the spring-summer of 1990 I started going out with my father around the city, downtown, just to look at the new things that were appearing. We used to go to the UNIC shop opposite the Italian church, to Romarta Children's where they had Lego on the ground floor, to Dumarex, which was at the entrance on Lipscani from the boulevard. We saw very expensive things, some we could afford, others we couldn't, they were sold in lei, dollars or marks, it didn't matter, we had money, and we had so and so. But beyond what you could or couldn't afford, there was the joy of discovering new things, whatever they were, Castrol oil, Delta ice cream, Kinder egg, it didn't matter. The summer of 1990 was one of the most exciting I can remember, full of discoveries, the Coppa del Mondo and CinCin chewing gum with footballer surprises. One day I asked my grandmother to call my father at work, at ACM3, which had not yet become SC MONOLIT SA, to tell him that I had a surprise with Marius Lăcătuș at CinCin. In the autumn of 1990, in front of our apartment block, at the intersection of Calea Văcărești and Mihai Bravu road, on the Dâmbovița wharf, a fair began to be organized which, by 1993, had become one of the biggest fairs ever held in a Romanian city. At the beginning, the fair was organized on the quay, on the traffic direction between the Vitan Bârzești bridge, from the bread factory, to the bridge near the Mihai Bravu metro station, where today there is a footbridge. It's a pretty popular video from those years, taken from a car, starting at the BIG intersection, going down Calea Văcărești and passing by the fair on a Sunday. In two years, the fair grew, it took over the other direction of traffic on the quay, and some people also sold their wares on the hillsides that were supposed to be the edges of the great reservoir that eventually became the Văcărești Delta. In the beginning there was nothing standardized or organized in any way, you went straight to the market and looked for what you were interested in. There were no stalls or designated spaces, everyone managed as best they could, some sold directly on the side of the road, others, usually those who came with clothes, would line up their jeans, tracksuits, leather and fur coats directly on the Dâmbovița fence, others came with chairs and folding tables on which they spread their things, but more often than not, the vendors drove their cars directly into the fairgrounds, covered their windows with towels and newspapers and turned the cars into huge stalls. Often, the cars were for sale. I was interested in fluorescent crayons and liners, some clothes that were popular with the kids, like FANATIC bermuda shorts, purses, hats, bicycles and computers. I got them all from the fair, the big fair that in later years was to be known as the Vitan Fair, by which time it had nothing to do with the weekly event of the early 1990s, at which hundreds of thousands of people would surely gather. One Sunday I got an HC91 computer with a Russian cassette player for uploading games, which I hooked up to a black-and-white Sport TV and so we had video games. Which didn't grab me, like cars, then or later. But it was easy for me to get the latest games for Romanian computers because I lived in an area where they were plentiful, either from the fair or from Big. The systematization of the upper numbers on Văcărești Way, between the intersection with Mihai Bravu and up to the intersection at Piața Sudului, happened between 1985 and 1988. In 1985 the tower blocks were built, the drawings of which appear in Gheorghe Leahu's personal work books. In the same year and in 1986 the 4-storey blocks on Pridvorului Street were built, and in 1988 the 7-storey blocks between the tower blocks, as well as the long block on the intersection, where I lived. The park at the Children's Palace, which today is called Children's World, was laid out, with a swimming pool and a summer amphitheater which were to form a complex for schoolchildren and young people. The amphitheater was never completed and never functioned, but the swimming pool opened in the summer of '89. That stretch of Calea Văcărești resembles in its architecture and uniqueness another stretch of Calea 13 Septembrie, also featured in Leahu's books. Officially, the segment was built for people who worked on the IMGB platform, unofficially, certain blocks and staircases were known to be inhabited by at least privileged people. However, in a tower block with a single staircase and four flats per level, out of the eight, last numbered at the intersection with Mihai Bravu as you walk towards Big, 63 children lived. I counted them together with a friend who lived there a few years ago, on a day when we had nothing to do. We were the first generation of kids to live in the Tineretului-Văcărești area, after the major transformations that happened in the 70's and 80's. I also remember all the cars in the parking lot behind blocks 1B, 1C and 1D where we lived. In the summer of 1991, I really wanted my parents to get me a bigger parrot, an Australian nymph or something. One afternoon while I was sleeping over at my grandparents' house for lunch, my dad came over with a fellow engineer from ACM3 who was driving and said, "Let me show you what I got!". We went out in front of my grandparents' villa and there in the parking lot was his colleague Gabi, driving a car as yellow as a chicken and looking like a communist car, although it had certain design features that took it out of the Eastern European car stereotype, but minor. I was extremely disappointed, I couldn't understand why he got a car if that was the car. Besides, it was clear to me that with this expense, there went my parrot. And so it was, anyway, my parents probably had no intention of taking my nymph. That evening, Gabi and I drove to the country with Gabi to my grandparents on my father's side, from Oarja, Argeș and back. We sat in the back and I was very sad, a noisy car that shook like a Trabant and my dad who kept trying to convince me that it was cool because it had a roof hatch, and all I thought was okay about it was the Blaupunkt audio system. All the way to the country and back, Gabi praised his car, which to me seemed like a jungo that you couldn't go over 90 kilometers per hour in and that I would have been ashamed to talk about with my schoolmates. In fact, the car was brilliant and now I regret all my thoughts of that time, with a design bordering between humor and Eastern European mannerism. It was a 1987 Wartburg 353, the penultimate model in the 353 series that Wartburg ever produced, with the 4-speed gearbox down low (not on the steering wheel, as before), the dash and the brown trim, funny and interesting at the same time. Immediately my dad started driving school with a very massive and tall instructor, Bogdan. He took the license exam on the first try and they hit the roads in the yellow Wartburg with license number 2-B-2264.

Clutch down, third

There followed many country trips in the Wartburg, which was so sloshing and shivering and we also drove with the hatch and windows open that even the cassette player could not be heard, no matter how loud my father played it, who kept playing Julio Iglesias and Demis Roussos tapes. In 1993 and 1994, that was pretty much the soundtrack for going to the country - and we went to the country quite often, about once every two weeks, which for me was nothing but missed weekends. In the fall of 1994, my dad drove the Wartburg to our dealership and sold it, I don't know how or why he decided he wanted a new car and bought a new, gray-metallic Dacia 1410 "Iliescu's Smile". Then he went to the fair again and got silver seat covers, they were some GLX polyester ones and an anti-theft device that linked the clutch pedal to the steering wheel. There were also some anti-theft ones that just locked the steering wheel, but the myths at the time were that those were more vulnerable, that there would be some cases of car theft where they would take the locked steering wheel out altogether, replace it with another one, and that's how the thieves got away with the car. So if the steering wheel was tied to the clutch pedal and you also had an alarm, you were considered safe. I don't think anyone ever tried to steal his Dacia, but he seemed to think they did. He kept that car for many years, a lot longer than it would have been useful, but he must have gotten used to it. The B-82-MTM was the car of my teenage years that I came home with from training and getting ready for admissions. By the time I was 17, friends from middle school and the neighborhood in Văcărești, some high school classmates from Central School, started getting driver's licenses and cars. I never imagined that I would have a license and a car, what to do with the car, where to go? I still think about why I would go by car, but most of the time I know I'm fooling myself. There were young people my age who couldn't wait until they turned 18 to get their license, neighbors who went to special driver's ed school, people who knew how to drive since they were kids and could finally drive legally. The distractions changed, we started going around town looking for them and things suddenly became different. Suddenly most of my generation realized that in one year we had single-handedly taught ourselves the city by looking for amusements more than we had in 18 years of life. We were everywhere, in a car or in a taxi, in Răcari, in the former Miraj factory, in Râmnicu Vâlcea, in Râmnicu Sărat, in Ambrozie, in Bobocica, in Moară, on Moșilor, in Sebastian, in Tei Toboc, on Viitorului, on Tunari, we were little gangs in which we felt invincible. And we were, for a while. Our neighbor, Americanu', had a Lada 1200 with which the whole neighborhood beat the whole city. Like so many of our neighbors on that side of town, he died around 2012 or 2013, and every time I remember him, I think of his Lada.

Clutch down, fourth gear

In the fall of 2001, my folks told me it was time for me to go to driver's ed school and get my driver's license. My dad got in touch with Bogdan, the instructor with whom he had also done the school 10 years before, and we started driving lessons. He had a white Dacia 1410, all "Iliescu's smile". I didn't like driving school, I felt there wasn't enough room in the driver's seat. I'd do an hour's driving, but after 40 minutes at the most, I didn't feel like it. We would usually meet at the bridge at Timpuri Noi, where before Băsescu's demolitions there was a kiosk very popular with taxi drivers, who were always stopping for coffee and other snacks. This Bogdan was a cocky guy who used to criticize all sorts of things to which I didn't pay attention, most of the time I didn't even listen to him, I answered him monosyllabically when I could tell from the tone of his voice that it was a two person conversation. He had this "clutch down" thing, he never said, "shift!" or "we're changing gear" or whatever, he always said: "clutch down first, clutch down second, clutch down third". I only heard him say "clutch down, fourth" once, when we were on Mihai Bravu highway, at noon, and it was quite empty, and he was in a hurry to pick up his boy from school, who was somewhere in Pantelimon. It was the only time I ever drove in fourth gear, and the highest speed I've ever driven: 50 miles per hour. All these things I didn't experience in any way other than that I couldn't wait to get out of the car. I failed the class twice because I didn't know which law book I was supposed to read from, and then Bogdan's car was stolen. Being self-employed and working in his own car, I had to wait a few months until he managed to buy another car. Eventually he got a Dacie like the one before and the day before the exam we drove a bit more on Văcărești and Tineretului. When I got out of the car, he asked me if I had read for the exam and made sure that I had read from the right book. Which is when I found out what the book was. I read it twice that night, the next morning I went to the exam, where I got 24 out of 26. I was entering the course, and if I failed, my driving school would expire and I'd have to start all over again. Our meeting point was Carol Halls in Filaret area, we were three guys waiting for the policeman and a blond lady with wavy hair came. I thought I would start the exam first, hoping that maybe she would make me go down the hill near the Carol Park, which was easy, I was going second. If he made me turn down the streetcar line to Heavy Traffic, I'd probably fail. I got into the car and the policewoman told me to take her to a club I knew, but I pretended not to understand the joke: - I'm sorry, I don't know, which way do you want to go, I asked her. - Go ahead, she answered me superior and I understood then that I was going to take the exam. I went down the hill near Carol, entered Candiano Popescu Street, where I parked and she let me out. After me, a guy got behind the wheel, who certainly knew how to drive better than me, and she repeated the joke about the club, but the guy made some jokes about clubs in Bucharest. She obviously failed him. So I've had my license since 2002, changed it once when it expired in 2012, then it expired again in 2022, but the last time I drove was then, on Filaret hill. In 2004, my father got rid of the "Iliescu's smile" Dacia, I don't know what he did with it, it had become a bit crappy, and so he ended up, again, in the Vitan fair. He came back with a Volkswagen Passat 1.9 TDI that he had no idea was going to become a cult model. It had 12,000 kilometers. Today it has 380,000 kilometers.