Revitalizing Europe's road infrastructure - between small and big actions

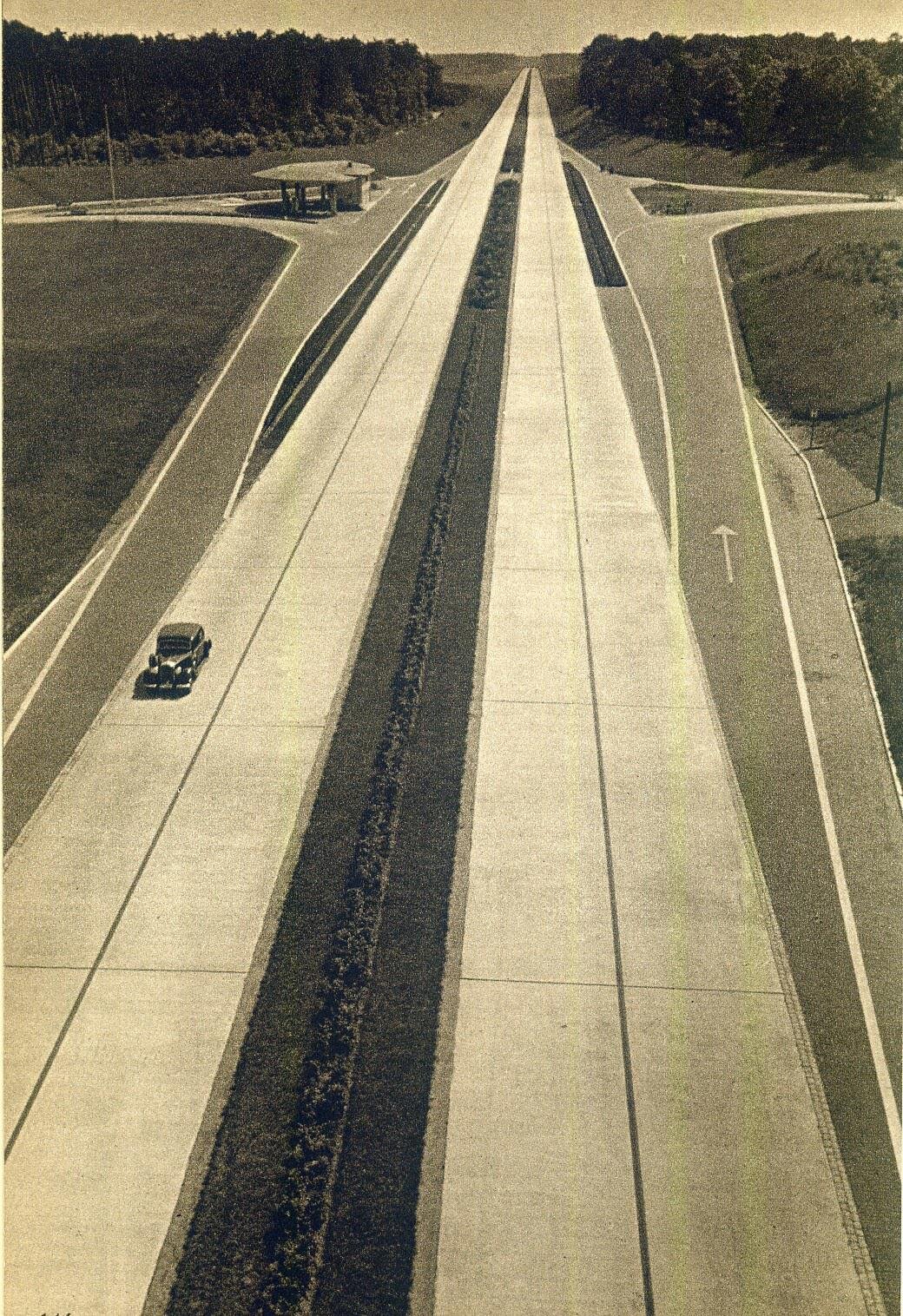

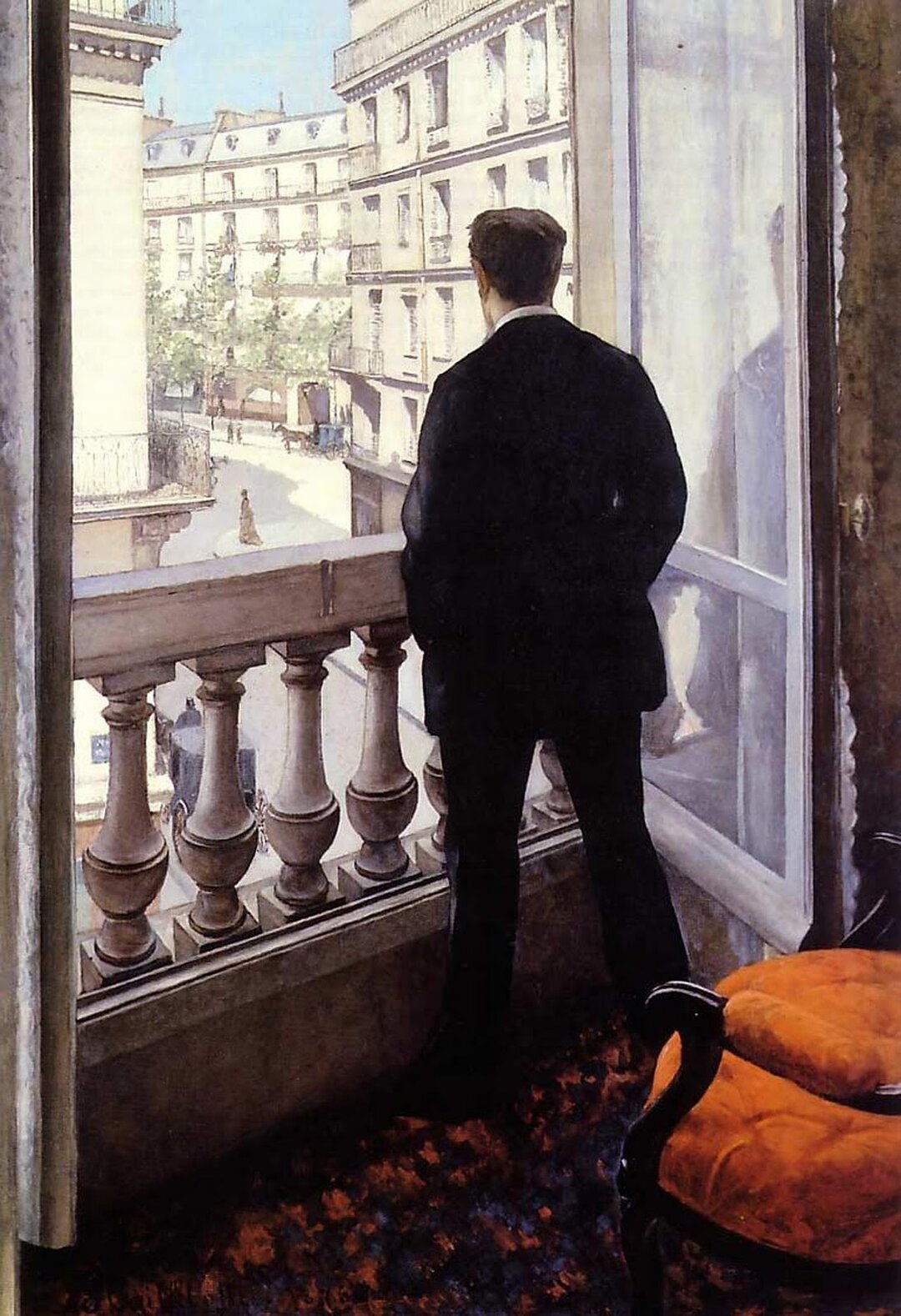

The last century has undoubtedly changed the face of cities with the widespread introduction of the automobile. Road infrastructure has adapted to these radical changes, and in addition to existing streets and boulevards, new types of roads have emerged, with their own demands and influences on the built environment. Bridges, viaducts or road overpasses, which used to cross mainly non-urban areas, have become massive sculptures in the middle of cities that are unknows to them, such as those in Europe. They cut through boulevards and streets, crossing them or running parallel, horizontally, above or below them, squeezing between buildings like uninvited guests. In many cases, they have left their mark on the neighborhoods and areas they pass through, leaving behind a myriad of effects, some arguably positive, others undoubtedly harmful to the townspeople.

The best example of the organic symbiosis of infrastructure and architecture dates back to the Middle Ages. Old inhabited bridges, where traffic was dominated by pedestrians, just like streets, were harmoniously integrated into the urban fabric as a natural extension of the street, all the way across the river. The new engineering creations, designed to serve mainly motorized traffic and less the ordinary pedestrian, monopolized this organic side of the street and often created around them a chaotic, parasitic residual space, vulnerable to social problems1.

The interval between the 1950s and the 1970s was the most feverish period in which hundreds of road overpasses were built in a fervor to bring the car into the midst of urban life. It was the desire to solve the problems of congestion and fluidity that sparked the wave of construction of these numerous urban overpasses and viaducts. With them, however, came the negative effects, as congestion worsened and fluidity remained the same. The unintended consequences of these insertions were strong, both physically and socio-economically. These massive infrastructures have left in their wake many broken-up neighborhoods, caused residents to move out more or less of their own volition, and created diffuse areas that have long been avoided by local authorities or private investors. Fortunately, the last few decades have brought back into the public sphere an interest in the development of deprived areas, including these areas affected by the presence of road infrastructure.

The need for space, rising urban land prices and socio-demographic and political changes have set the context for creative discussions about the urban buildable space so valuable in European metropolises. It has been recognized that the residual space around bridges or viaducts is primarily a viable land resource, which many private investors as well as public administrations have taken into consideration. From grassroots actions and participatory urbanism to true master plans and strategies, they aim to regenerate and revitalize these areas of potential. The need to use this space has created the opportunity for their functional conversion by partially or totally stopping cars. In few cases demolition measures have been undertaken.

The most common intervention is infill, when the intrados of an infrastructure is occupied by commercial and related activities, ranging from shops to fitness centers or art galleries. The once dead space underneath is thus infused with human activity, resulting in a decreased risk of abandonment and crime. This measure of filling vacant space with various functions by planting infrastructure is increasingly common in major cities around the world. The lack of central undeveloped space makes any land resource a potentially valuable site.

In Prague, the northern embankment of the Vltava River has been transformed into a promenade some four kilometres long, and the wall under the road has been repurposed by converting the 20 cellars that make up the Vltava River (fig. 1). Part of a wider strategy to revitalize the river, the 2019 project consisted of a modular design designed to fit efficiently and uniquely into the tight spaces for each cellar (fig. 2)2. Cafes, clubs, studios, workshops, art galleries and other spaces for the public brought the site to life. The cultural-commercial insertion intended by the project has made the riverbank attractive to passers-by, while creating flexibility in the space when needed.

© BoysPlayNice Photography / Jakub Skokan & Martin Tuma / © Petr Janda | Brainwork

© Petr Janda / Brainwork

On the south bank of the Thames in the 1950s, an infill was built under Waterloo Bridge to house England's largest independent cinema, along with the National Film Archive. In 2018, an architectural infill was completed under the bridge to respond to new needs for circulation flows and other cultural facilities within the cinema3. As such, the team at Carmody Groarke Office envisioned a translucent, transparent and luminous volumetry that forms a dynamic complementary relationship with the Brutalist architecture of the area. The new entrance to the existing complex opens to the exterior occupied by the promenade that accompanies the river, with a glazed ground floor inviting the public inside (fig.3). The bridge becomes a veritable roof, protecting the public space in front of the new extension and forming together with it a cohesive whole.

BFI Southbank

© Luke Hayes & Carmody Groarke

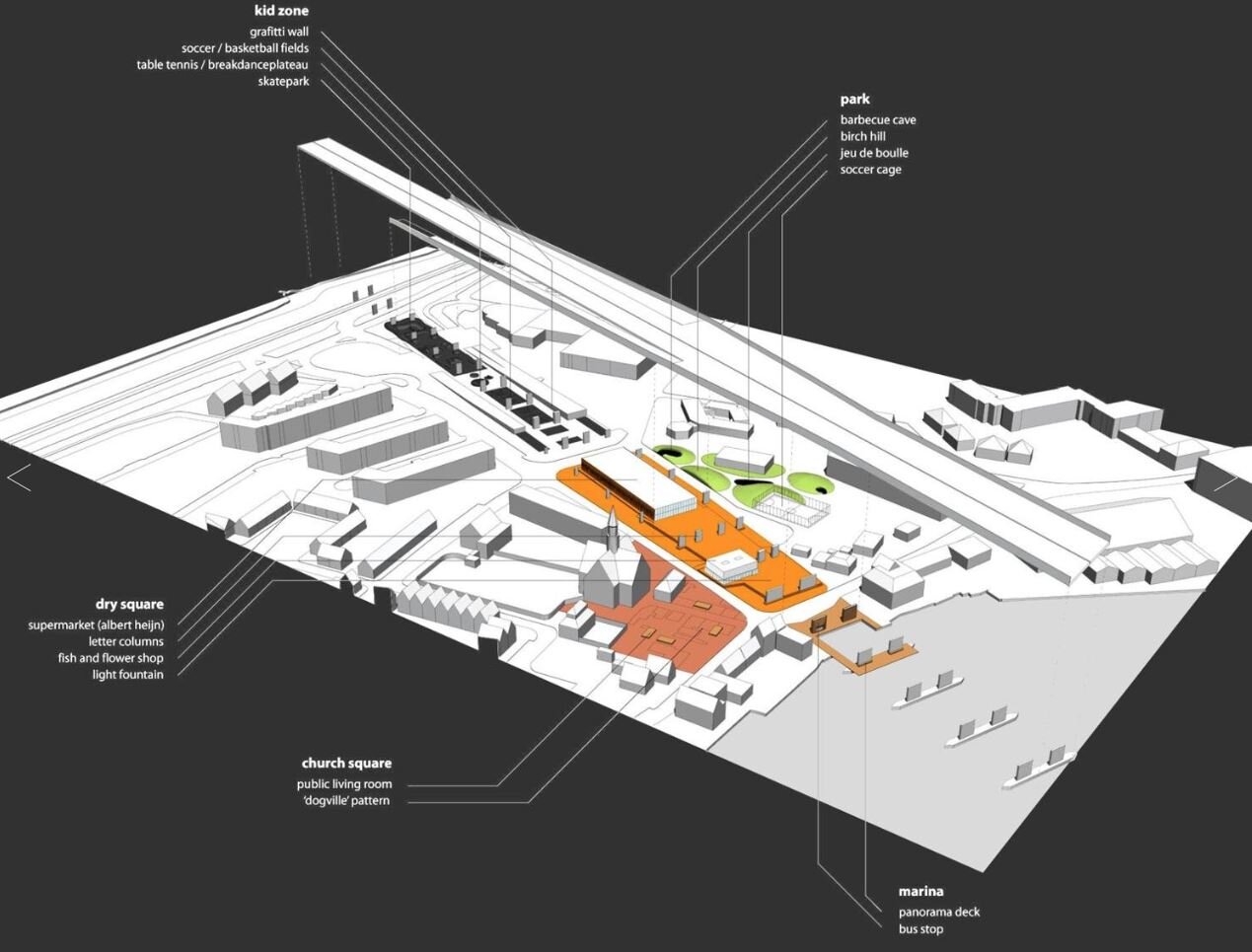

In contrast to the two culturally charged examples, the Dutch architects from NL Architects opted for a more commercial use of the space under the A8 suspended highway in the small town of Koog aan de Zaan. From the outset, the highway was a physical barrier that divided a space tightly knit around the church and the old town hall4. The link between them was inevitably lost with the realization of the highway in the 1970s, but in 2003 the local authorities started the process of recovery by creating new connections. A supermarket from a popular Dutch chain became the commercial attraction of the area, physically materialized in a bright space bordered by glossy white tin panels under the concrete floor. The rest of the space has been valorized with new sports and play areas, squares and even a small deck overlooking the river. The two areas around the town hall and the church were also included in the project, forming together with the intrados of the passage a string of public spaces designed to reconnect north and south (Fig. 4).

© NL Architects, 2006

While operations on the basis of serious revitalization projects with concrete and permanent actions tend to have positive results in the long term, smaller projects encounter difficulties later on. Once their period of operation is over, many of these projects are remembered as experiments without an immediate permanent transition. Bureaucracy, differing policies of the authorities or lack of funding all mean that such projects do not have the continuity of long-term urban operations. More often than not, these projects do not aim at permanent construction under the infrastructure, but rather emphasize urban landscaping with public spaces and possibly temporary and easily demountable buildings.

Folly for a Flyover, implemented under a road overpass in East London, was a project dedicated to cultural events and functioned as a temporary architectural installation over a six-week period. A neglected space, partly bordered by the concrete of the bridge but also by the River Lea, was transformed into an open-air cinema where people could come and watch movies, drink coffees and admire art installations (fig. 5). Assemble, the team behind this initiative, invited the local community to participate both in the creation of this architectural installation and to enjoy this newly refunctionalized place5.

Folly for a Flyover

©Assemble

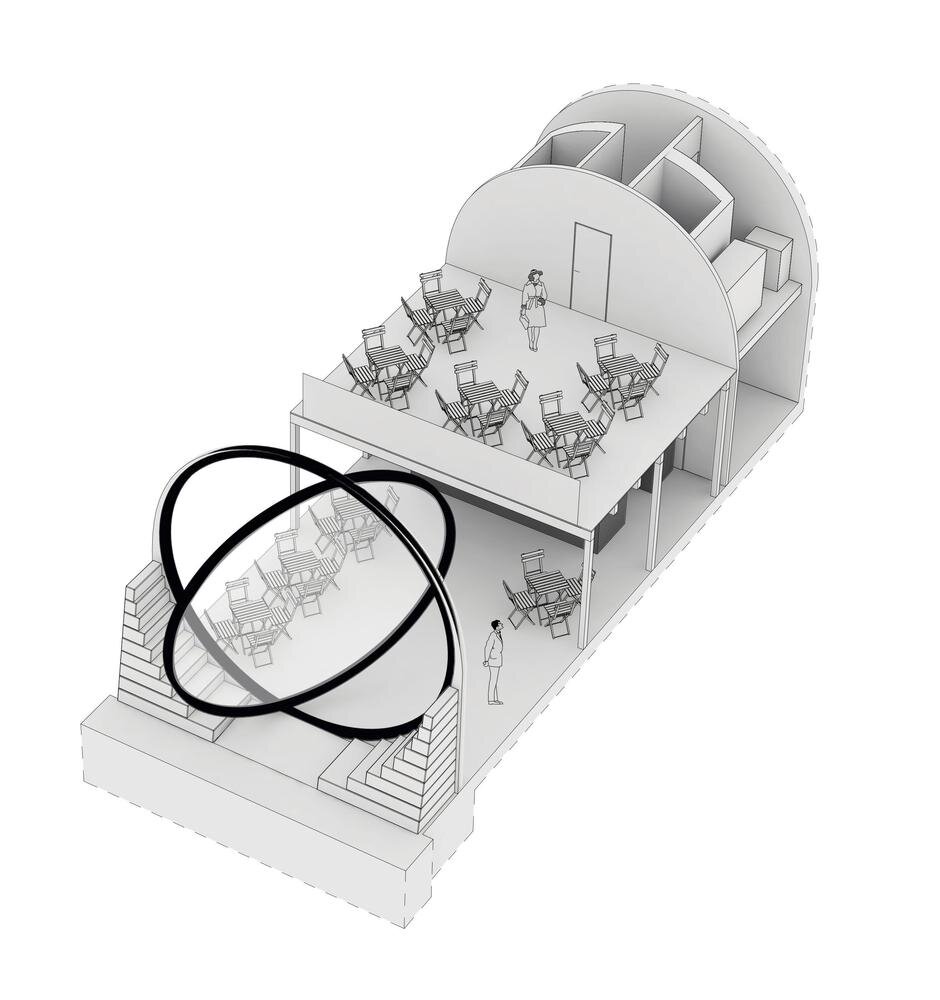

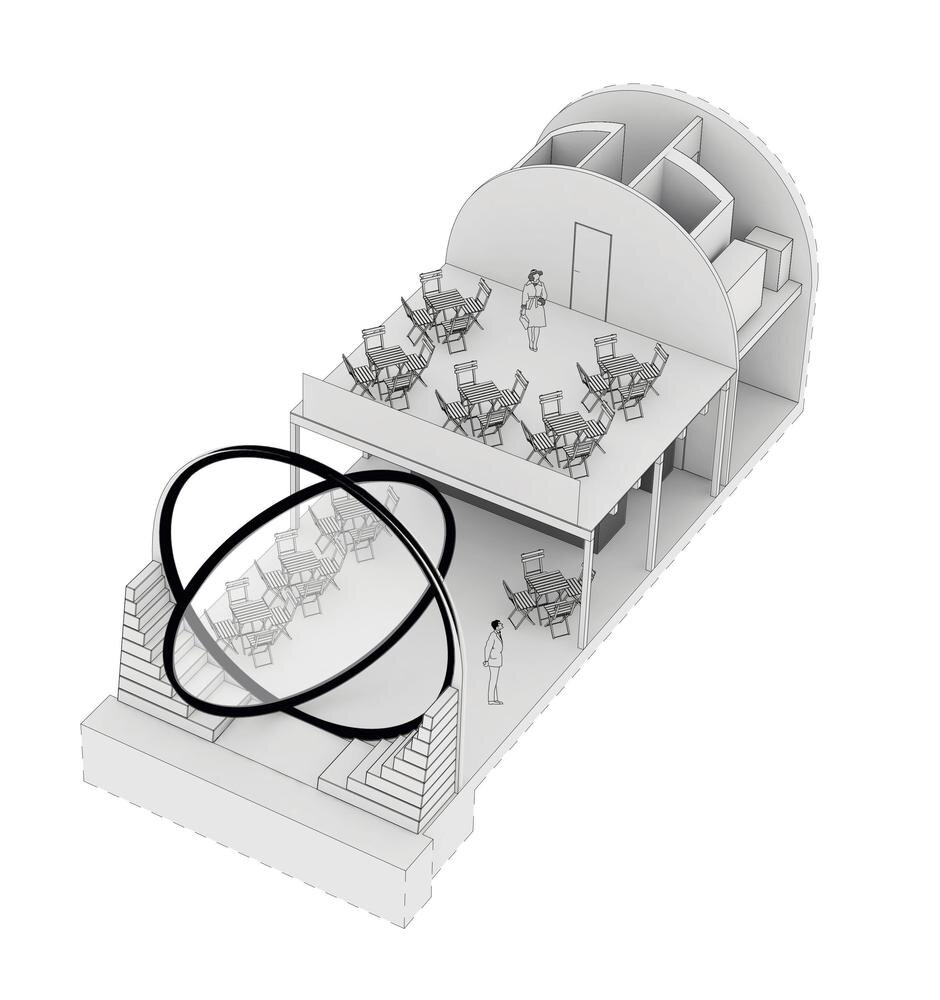

A similar project was implemented by architects from two architectural offices, Atrium Stydio and Esterni, in Slovakia. Part of a larger project, prepared on the occasion of Košice's designation as European Capital of Culture in 2013, the project temporarily transformed a run-down and socially vulnerable site into a cultural and sports space6. The team of architects wanted to reclaim the derelict space of an abandoned road bridge through lightweight, removable wooden structures. The focus was on community by creating a gathering place, with a makeshift amphitheatre made of wooden bleachers on the bridge embankment, a stage and sports areas and a small café. There was no shortage of effective artificial lighting to create a totally different atmosphere from that generated by the concrete of the overpass (Fig. 6). The project had a happy ending, as the area continues to function today as a skatepark-type sports venue.

--17309-xl.jpeg)

Sport center Under the Bridge

© Atrium architekti

The G124 architects led by Renzo Piano attempted a similar intervention in Rome. Their project, Sotto il viadotto (Under the viaduct), was part of a wider strategy to use the European Union's TUTUR(The Temporary Use as a Tool for Urban Regeneration) mechanism. The choice of a semi-abandoned infrastructure such as the Viadotto dei Presidenti, which crosses the northern outskirts of Rome, was a natural choice in an attempt to save a vulnerable and derelict area, even temporarily. The aim was to transform the residual underbelly into a useful public space that could act as a starting point for the future regeneration of the surrounding neighborhoods7. The architects wanted to involve the community through workshops, presentations and participatory/tactical urban planning throughout the implementation of the process8. The minimal interventions consisted in the creation of urban furniture objects out of pallets, tires and various recycled objects (fig. 7). Also, two containers served as temporary workshops, and the only component of the intervention that still survives today is the pedestrian alley with bicycle path that crosses the space under the underpass.

Sotto il viadotto (Under the viaduct)

© Agnese Samà, arch – G124

Scottish architects 7N Architects and landscape architects RankinFraser Landscape Architecture have also made use of urban installations with their Phoenix Flowers project. This was implemented in 2010 and was part of an urban regeneration project in Glasgow's historic city center9. The monotonous and dangerous character of the transit space under the suspended route of the M8 motorway was tamed by the proposed urban design. The design placed a strong emphasis on color to counter the grayness of the infrastructure, and the light installation brought a welcome reassurance to the pedestrian route crossing the bridges underneath (Fig. 8). Implemented with the support of local authorities, the project is still working.

Phoenix Flowers

© 7N Architects

Unfortunately, things have not necessarily changed for the better in both the London and the Italian cases after the end of the operational period. Lessons have been learned, but bureaucracy, different development priorities or simple carelessness have not led to the changes for the better that were initially so much desired. But the Slovak and Scottish examples have shown that, with interested public authorities, temporary experiments can continue in the future.

The most common and easiest way to use these places is a softer approach, without including them in any large-scale strategic urban revitalization or regeneration operation. Wherever we find suspended infrastructure within cities, there is the possibility that stretches of it may be occupied underneath by spontaneous or improvised commerce - agri-food markets, periodic fairs or simple stalls. In most cases, however, they function either as landscaped or undeveloped parking lots or simply as transit areas. In this way the space is used, even if not in the most interesting way, and maintenance costs are minimal. Such interventions involve urban design and landscaping, with an emphasis on greening to combat pollution, along with graffiti and mural art to hide the gray of concrete pillars and beams of infrastructure.

In London, local authorities have greened the underside of the Hammersmith Underpass with planters and plant screens to reduce traffic pollution (fig. 9).10 In Bratislava, to improve the appearance of a bus station under a junction of road overpasses, a civic organization together with the team from Vallo Sadovský Architects painted the asphalt green and yellow for the road markings (fig. 10)11. With this intervention, they wanted to draw the authorities' attention to the unkempt appearance of the terminal, while at the same time creating an improved visual image.

--17312-xl.jpeg)

Hammersmith A4 'Fly-Under'

© Meristem Design

Green Square / Urban Interventions

© Pato Safko, arh - Vallo Sadovský Architects

In Bucharest, road overpasses are the order of the day in a city where cars still dominate the space, and dealing with parking is a matter of general concern. Relieving congestion by encouraging high-speed traffic remains a priority, and to this end, the overpasses are being maintained in their current form, with no particular changes. The local administration has used the height of the Basarab overpass infrastructure to squeeze even more parking spaces by means of an intermediate platform above the ground (fig. 11, 12). We thus see an attempt to make a vast space more efficient while at the same time satisfying drivers. In the current situation, it is still premature to speak of spontaneous or strategic interventions that also prioritize pedestrians.

Road infrastructure, particularly suspended road infrastructure, can function as a skeleton to which a new urban breath is attached. Human activities are necessary to transform a vague and uncertain place into a pleasant, attractive and economically profitable space. Be it a supermarket, an art gallery or a simple landscaped promenade, these interventions can change the character of a place and can also reconnect once fragmented areas. But a strong dose of interest is needed, from local authorities, private individuals and ordinary citizens who can demand a paradigm shift.

References

Galdini, R. (2020). Temporary uses in contemporary spaces. A European project in Rome. Cities, Vol. 96

Patti, D., Polyak, L. (2017). Frameworks for temporary use: Experiments of urban regeneration in Bremen, Rome and Budapest. In Henneberry, J. ed. (2017). Transience and Permanence in UrbanDevelopment

Van't Hoff, M. (2016). Underneath Rails and Roads. In Glaser, M. ed. (2016). The city at eye level: Lessons for street plinths, Eburon Academic Publishers, Utrecht, Netherlands

Zanzottera, F. (2018) Italian outskirts: reflections for a debate. In A. Conti, G.A.T., Martínez, eds.(2018). 30 x 40 x 50 SUBURBS OF THE WORLD MINOR CITIES Pará de Minas: Built environment and social life, Do A Edition Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Assemble (2011), Folly for a flyover, online, available at: https://assemblestudio.co.uk/projects/folly-for-a-flyover

Revitalization of Prague's Riverfront / petrjanda/brainwork (2019), online, available at: https://www.archdaily.com/942192/revitalization-of-pragues-riverfront-petrjanda-brainwork

Carmody Groarke (2019), BFI Southbank, online, available at: https://carmodygroarke.com/work/bfi-southbank

Atrium Architekti (2013), Sport center Under the Bridge, online, available at: https://www.atriumarchitekti.sk/en/architecture/urban/sport-center-under-the-bridge

7N Architects (2010), Phoenix Flowers, [Online], available at: https://www.7narchitects.com/projects/phoenix-flowers

Green Square Urban Interventions / Vallo Sadovsky Architects, online, available: https://www.archdaily.com/177428/green-square-urban-interventions-vallo-sadovsky-architects?ad_medium=gallery

Hammersmith a4 'fly-under' receives a green makeover to help combat air pollution, online, available at: https://www.meristemdesign.co.uk/news/2019/1/7/meristem-green-screens-are-pedestrians-first-line-of-defence-against-air-pollution

Notes

1 Patti, D., Polyak, L. (2017). Frameworks for temporary use: Experiments of urban regeneration in Bremen, Rome and Budapest. In Henneberry, J. ed. (2017). Transience and Permanence in Urban Development, 231-248.

2 Revitalization of Prague's Riverfront / petrjanda/brainwork (2019), [Online], available at: https://www.archdaily.com/942192/revitalization-of-pragues-riverfront-petrjanda-brainwork.

3 Carmody Groarke (2019), BFI Southbank, [Online], available at: https://carmodygroarke.com/work/bfi-southbank.

4 Van't Hoff, M. (2016). Underneath Rails and Roads. In Glaser, M. ed. (2016). The city at eye level: Lessons for street plinths, Eburon Academic Publishers, Utrecht, Netherlands.

5 Assemble (2011), Folly for a flyover, online, available at: https://assemblestudio.co.uk/projects/folly-for-a-flyover.

6 Atrium Architekti (2013), Sport center Under the Bridge, online, available at: https://www.atriumarchitekti.sk/en/architecture/urban/sport-center-under-the-bridge.

7 Galdini, R. (2020). Temporary uses in contemporary spaces. A European project in Rome. Cities, Vol. 96, 102445.

8 Zanzottera, F. (2018) Italian outskirts: reflections for a debate. In A. Conti, G.A.T., Martínez, eds. (2018). 30 x 40 x 50 SUBURBS OF THE WORLD MINOR CITIES Pará de Minas: Built environment and social life, Edition Do A Belo Horizonte, Brazil, pp. 23-36.

9 7N Architects (2010), Phoenix Flowers, online, available at: https://www.7narchitects.com/projects/phoenix-flowers.

10 Hammersmith a4 'fly-under' receives a green makeover to help combat air pollution, online, available at: https://www.meristemdesign.co.uk/news/2019/1/7/meristem-green-screens-are-pedestrians-first-line-of-defence-against-air-pollution.

11 Green Square Urban Interventions / Vallo Sadovsky Architects, online, available: https://www.archdaily.com/177428/green-square-urban-interventions-vallo-sadovsky-architects?ad_medium=gallery.

--17314-xl.jpeg)

--17315-xl.jpeg)