Urban evolution in relation to transportation evolution

The evolution of cities and then urban systems, in terms of their size, structures, morphologies, densities, and ambience, has been influenced throughout history by a multitude of factors, perhaps the most powerful of which have been the progress of science and technological innovations, particularly in the fields of transportation, communications and information.

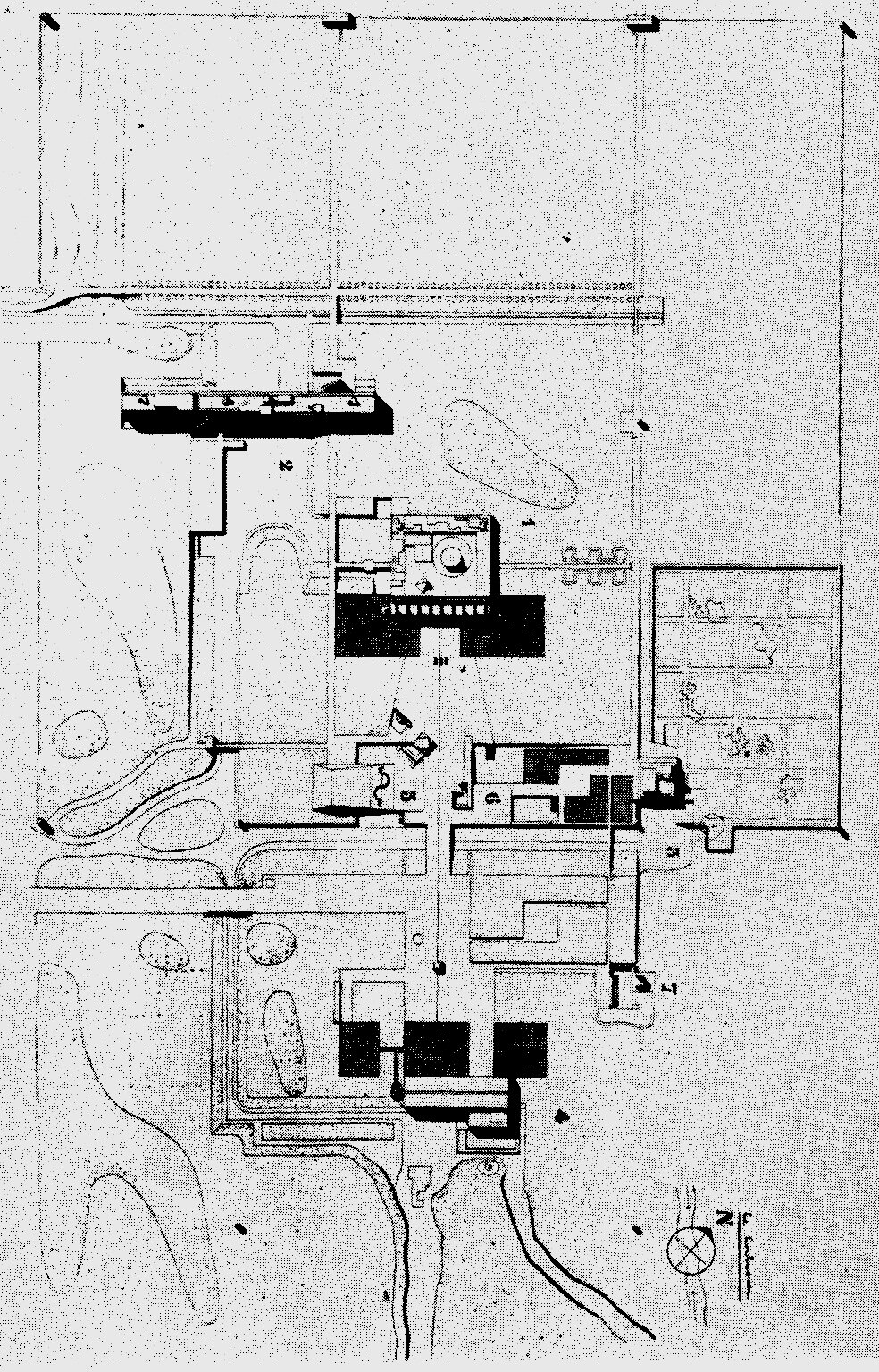

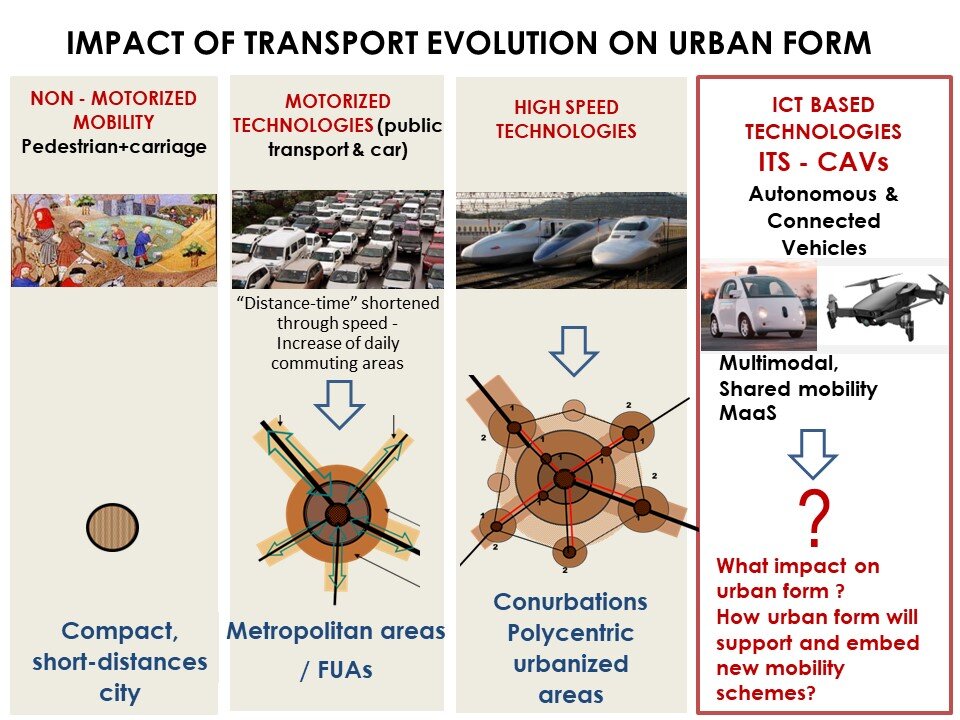

Human settlements, as systems of localized activities, have always been calibrated by the possibility of covering the distances between them, on a daily basis, within a limited and acceptable time span. Until the 18th century, before the advent of motorized transport technologies (train, urban public transport, car), settlements were on a "walking scale", with average diameters of 5-7 km (Fig. 4). Horse-drawn carriage was mostly limited to the movement of goods within and outside these settlements. The possibilities for extensive farming were also limited by the defensive walls, which were very difficult and costly to rebuild in larger enclosures. The development of human settlements in the long phase of 'walking' (non-motorized transport) was therefore intensive, with extreme densification of a small territory, leading to a high homogeneity of settlement patterns and intensity of land use. The silhouette of these towns, of which the medieval town is considered to be the archetype, was marked by only a few representative buildings of secular and religious power. The street layouts were predominantly narrow, organic or geometric (in the case of towns built on the basis of plans), with only a few wider roads for military parades or religious processions.

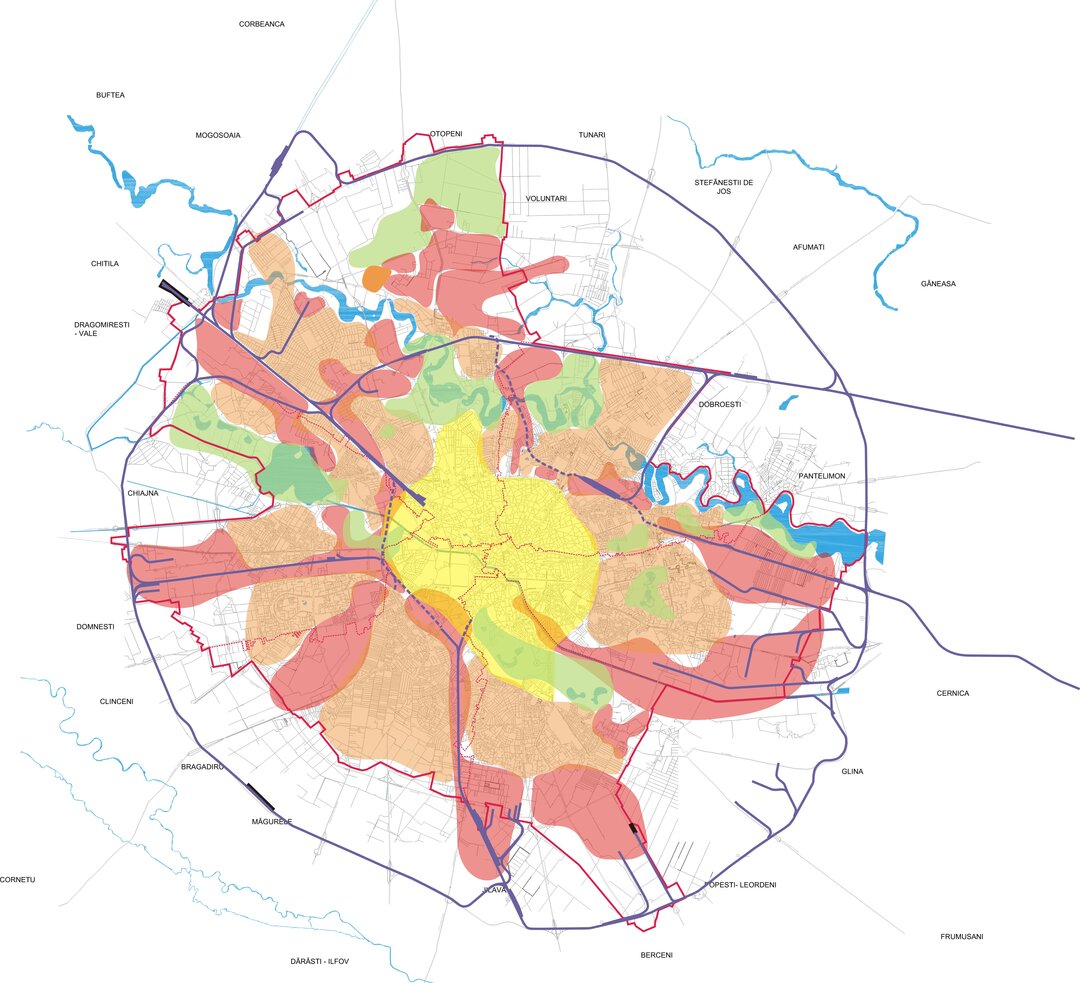

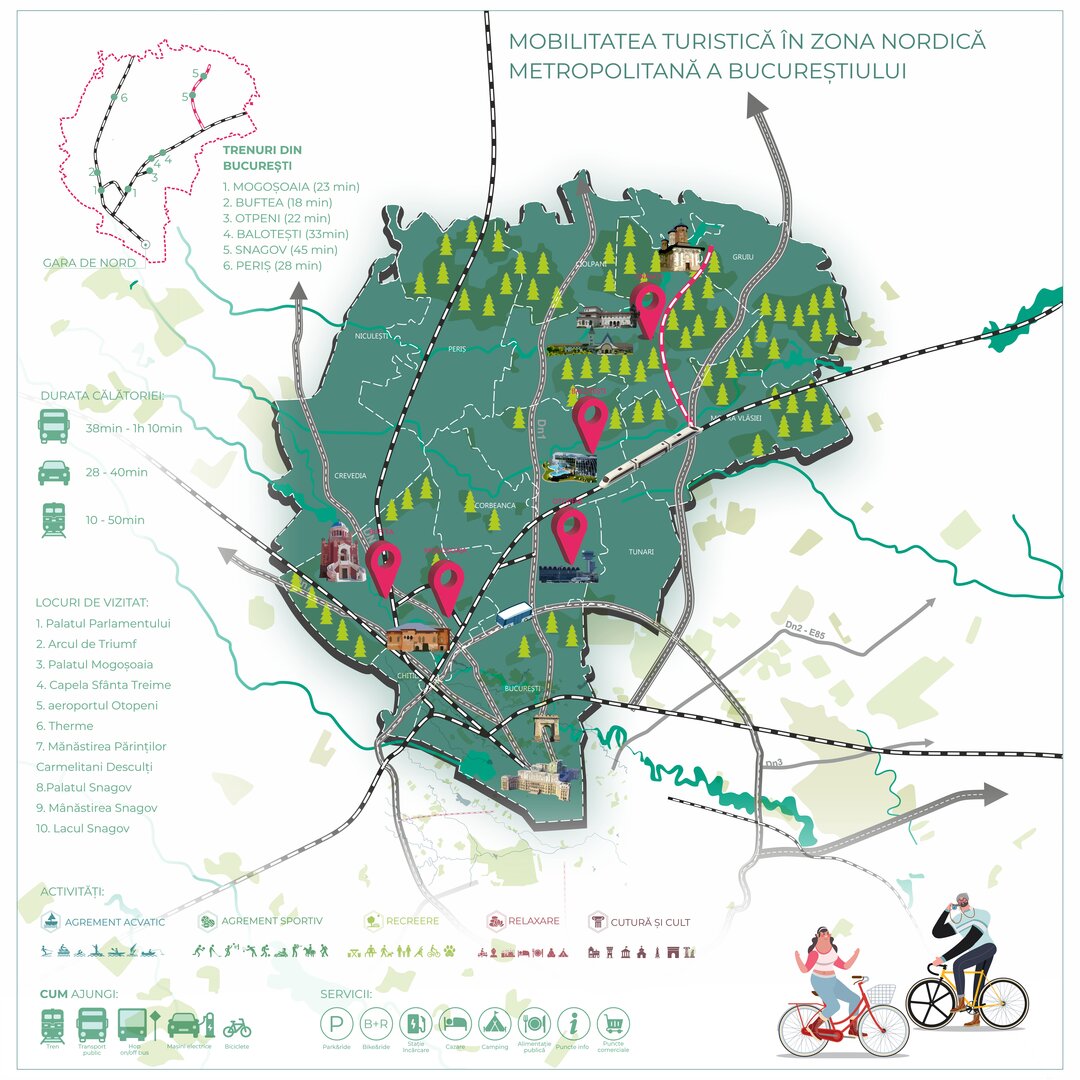

With the advent of mechanized and then motorized transport technologies, and with the development of their speed performance, an interesting change in the substance of distance occurred. From a metric notion in the context of urban life, it has become a chrono-metric notion. When we travel distances between various localized activities, the time required to cover that distance has become preeminent in relation to the length of the route traveled by a vehicle. Modern transport has therefore given distance a temporal dimension, becoming distance-time, relativized by the speed of travel. Travel budget time (travel budget time) is a part of the daily 24-hour time budget which is divided between various activities: work, relaxation, travel, sleep, etc. It is therefore limited so as not to affect the availability of time for other activities. Yauco Zahavi showed in his studies in the 1960s that, irrespective of cultural or technological context, the travel time budget in big cities has been constant over time, averaging about 1h 15'. Cesare Marchetti also studied the average time spent commuting in the 1990s, and identified the Marchetti constant of about an hour round-trip, or half an hour round-trip/half an hour round-trip. It is this half-hour time-distance that calibrates theterritory of the commuting commuting basin, which has transgressed administrative boundaries over the last 70 decades, starting in the 1950s on the American continent and in Western Europe, and for about three decades in Western/Eastern Europe. The higher the level of development of traffic infrastructure and transport services at the regional metropolitan level, the more extensive these areas of daily flows are, and the stronger the force of attraction-polarization of the urban system in the hierarchy of the European urban fabric.

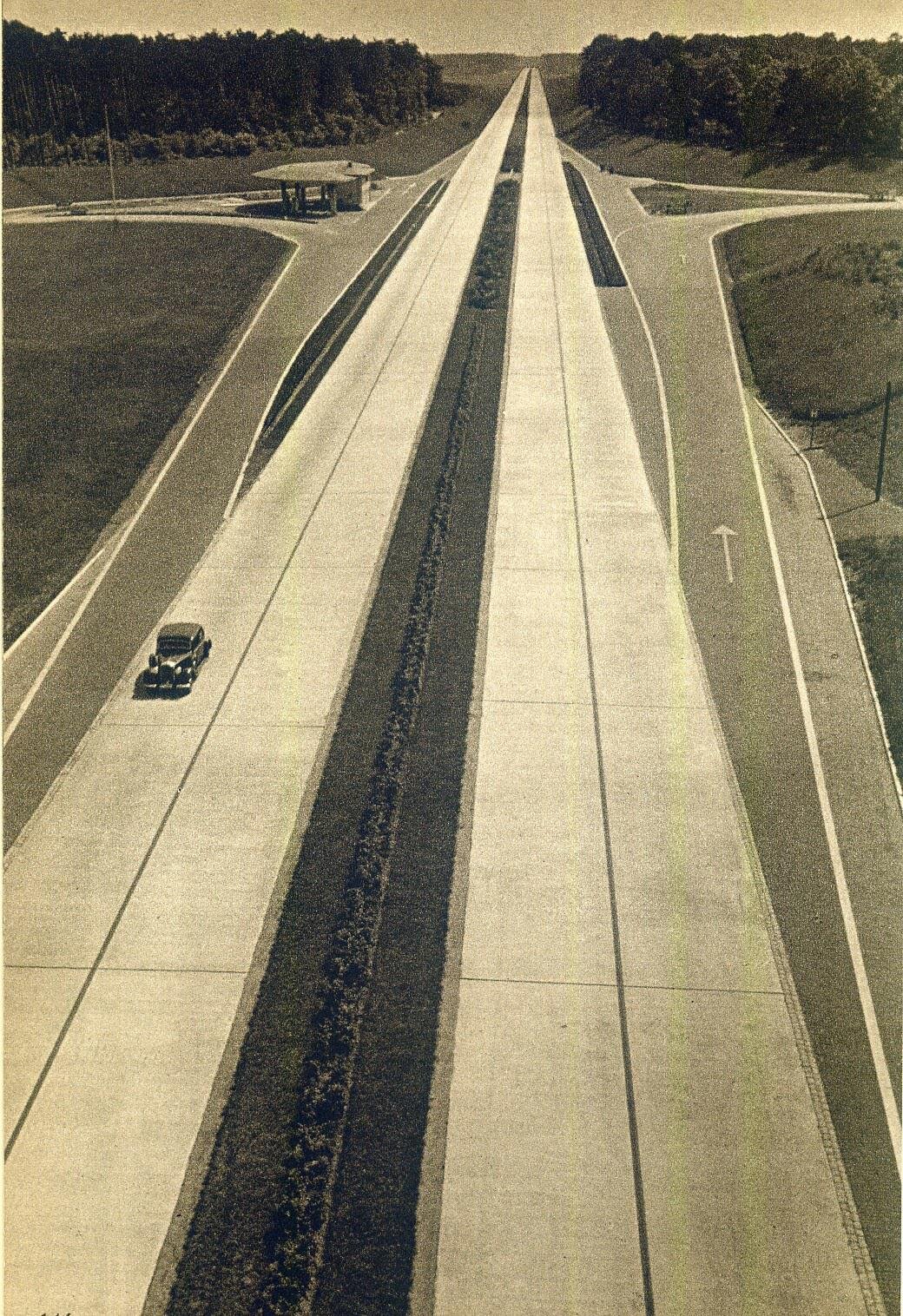

With the advent of the train, omnibuses and then the automobile, the time-distance associated with the daily travel budget progressively increased and cities began to expand in ever larger areas as the speed performance of vehicles evolved, highways were built and the rate of motorization increased.

It can be argued that the process of peri-urbanization and later metropolization was generated and driven by rail and automobile transport. Urban has become territorialized, no longer a notion strictly linked to the administrative unit called the city, but a concept associated with an urban way of living on larger territories, integrating several administrative territorial units into urban systems. Today's urban is a territory of everyday flows forming Functional Urban Areas - (fig. 4).

Much more complex urban structures have become polycentric. Urban morphologies have diversified, both as a result of the evolution of building patterns, techniques and technologies, cultural trends, but also as a result of the marked differentiation of land prices over increasingly vast territories. The low cost of land in peri-urban areas and the freedom of movement provided by the automobile have been the driving forces behind the process of urban sprawl, with low-density, predominantly residential, low-density urban fabrics, which are functionally highly dependent on the city around which they have developed and towards which they are developing ever-increasing commuter flows, exceeding existing road capacity.

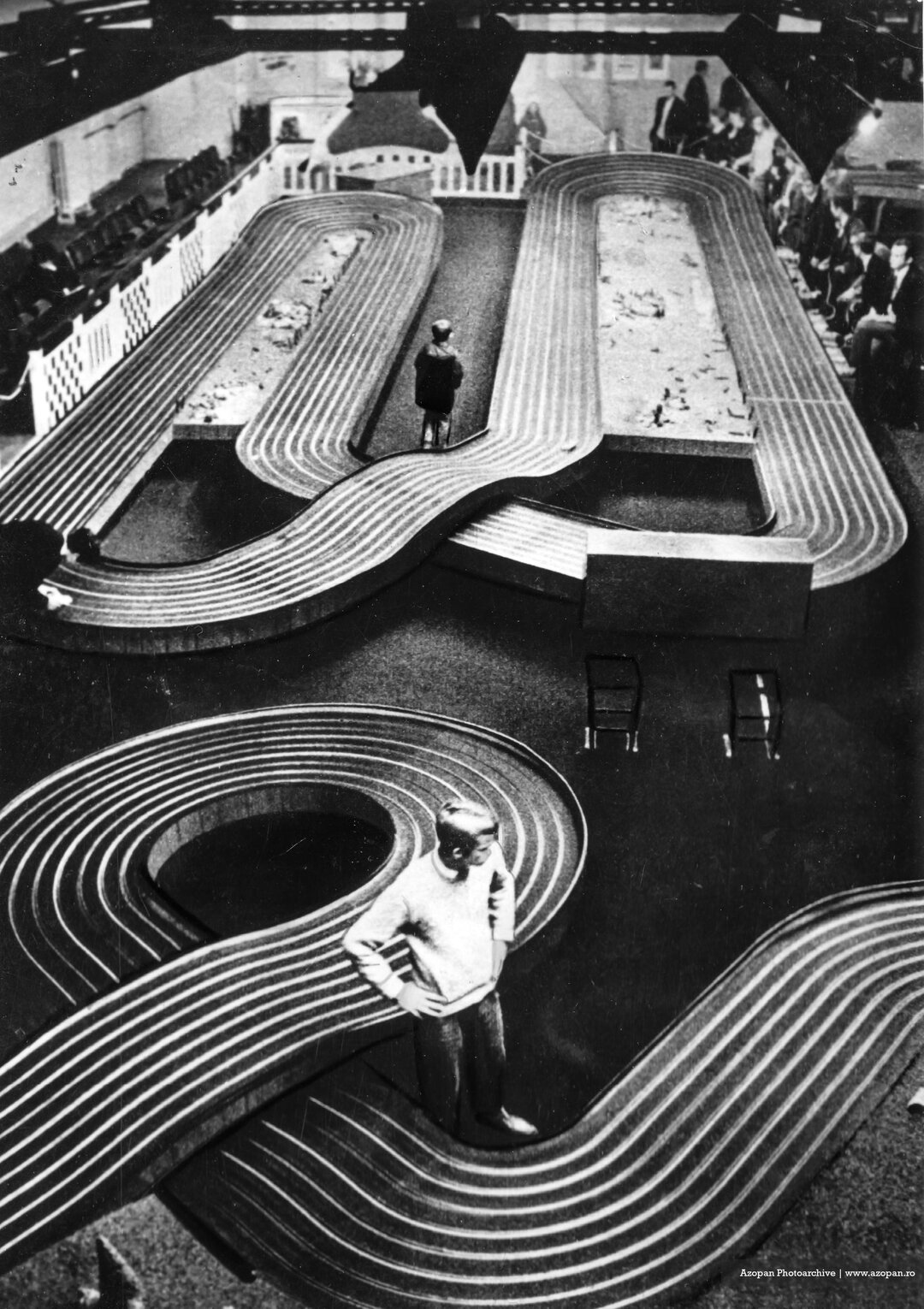

With the increase in the rate of motorization, in the face of the bulimic demand for traffic and space generated by the automobile, the paradigm of adapting the city to the automobile was adopted. Since the 1950s, in the countries of Western Europe, highways have been built, street layouts have been extended and reshaped in a logic of adapting the city to the car, associated with the term 'traffic fluidization'. Public spaces - streets, squares and urban squares - have been transformed by traffic engineering into traffic corridors and parking areas for several decades, losing their anthropological role as spaces for community life, with environmental and aesthetic requirements. The automobile, a major polluter and consumer of urban space, has contributed to what in the history of urban planning is known as the "urban decline" phase, i.e. a centrifugal development dynamic associated with the degradation of city centers and, in general, of most public spaces (Fig. 1).

© Foto Mihaela Negulescu

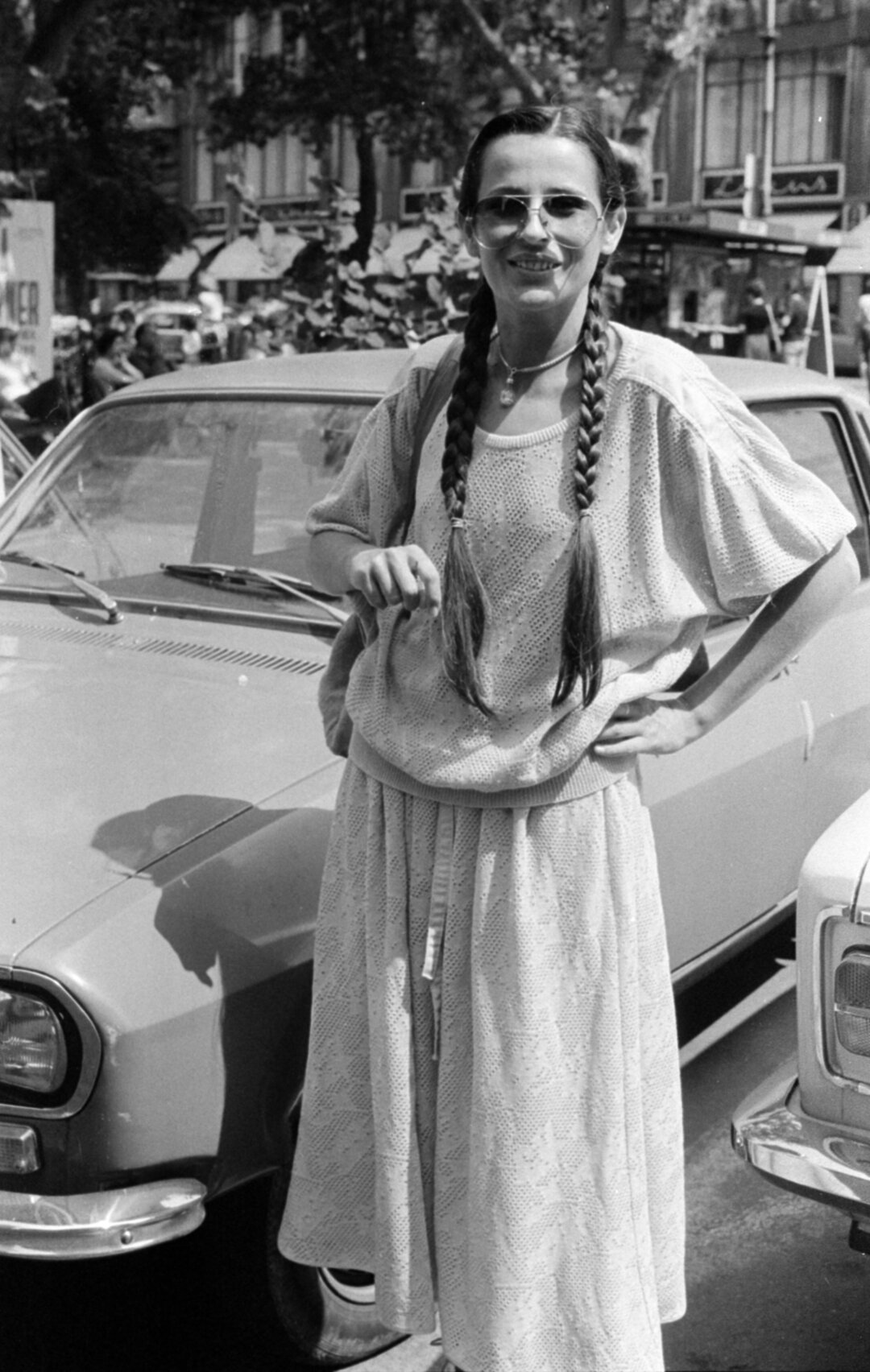

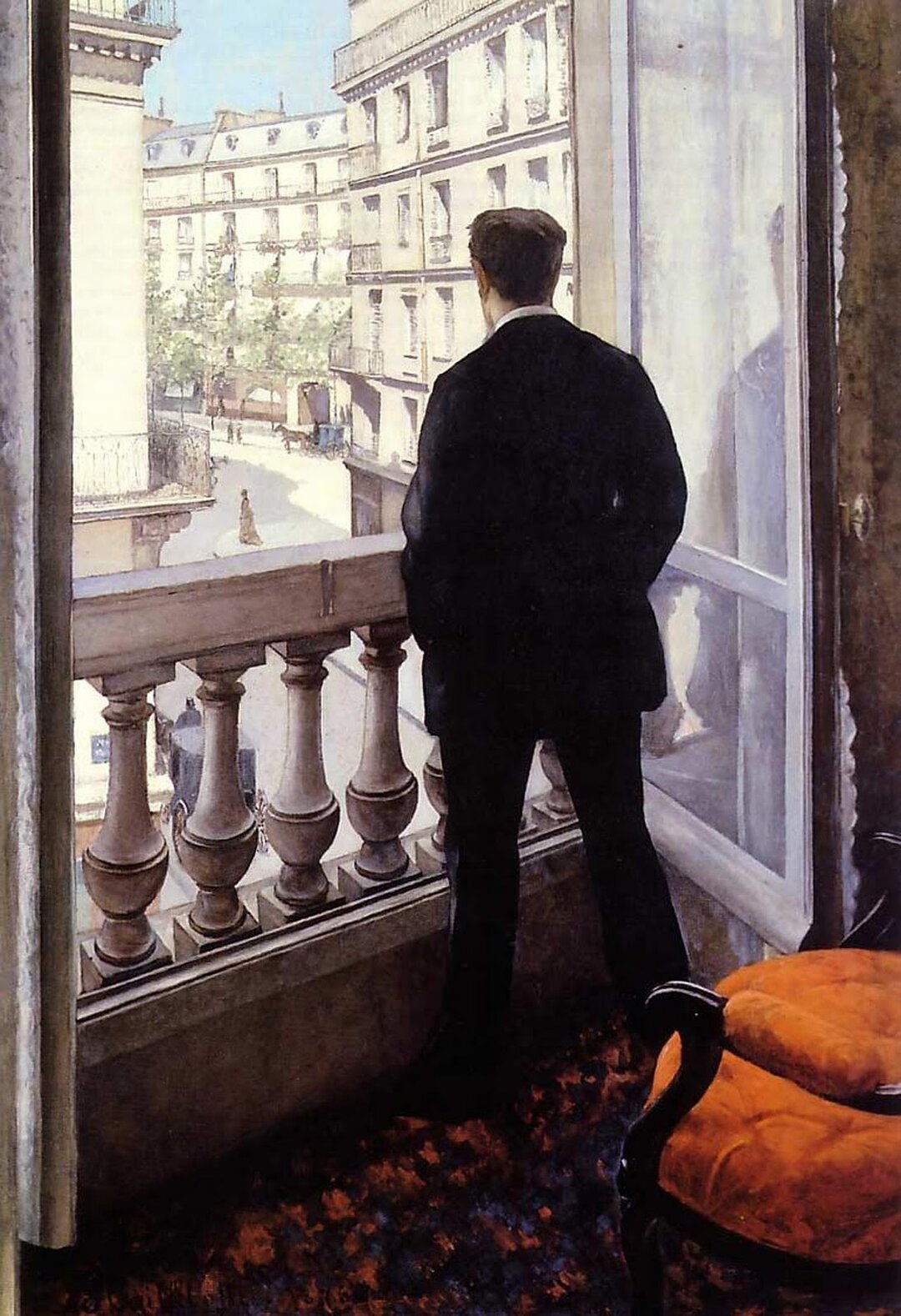

In the 1970s, pollution generated by traffic and classic industry was a determining factor for the emergence and development of the ideology of sustainability. The incorporation of urban mobility into this new logic has generated an important paradigm shift that requires difficult and long-term changes. The major challenge is to reduce pollution and curb climate change by reducing the role of the car in movement systems as quickly as possible through a (multi)modal restructuring of flows. The new paradigm of sustainable and intelligent mobility is coupled with a new urban paradigm of reshaping the 'city for people', with a focus on improving the quality of urban living through urban regeneration and rehabilitation of public spaces (Fig. 2). Remodeling of streets and urban squares in the major and secondary road network is taking place, often based on reducing the space for moving and stationary cars, in order to regain the status of a pleasant and safe living space with enhanced aesthetic and identity value. The 'complete street', 'pedestrianized' and 'shared-space' models are making a comeback. All urban regeneration interventions are necessarily based on new, contextualized, multi-modal mobility schemes in which the car is literally and figuratively losing ground, while public transport, non-motorized travel and shared (micro)vehicle systems, i.e. less polluting and less space-consuming travel options, are gaining in importance. Spatial development planning is becoming increasingly integrated with urban mobility planning to reshape urban mobility in support of urban regeneration.1 In this respect, integrated UM (Urban Planning and Urban Mobility) concepts are now emerging to guide planning in both areas, such as the 'walkable neigbourhood'2, the '15 minutes city', the 'superblock' and others.

Over the last two decades, the development of high-speed and long-distance transport has resulted in a very short time-distance of 1-3 hours between major European cities connected by the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T), indicating a trend towards their aggregation into conurbations and even future continental macro-megalopolises.

Thus, motorized transport and, in particular, the automobile, have played a major role in the spectacular evolution of urbanization over the last century, in its growth in size and complexity, with associated structural and morphological transformations.

Today, we are witnessing the emergence and accelerated development of intelligent mobility, with new technologies such as autonomous, robotized, and flying vehicles for aerial urban mobility already announced (Fig. 3). It is not yet sufficiently anticipated what the impacts of future intelligent transport systems will have on the urban, in a context in which other potentially restructuring transformations for spatial organization are also taking place, such as, for example, digitization and virtualization (de-localization) of activities (Fig. 4).

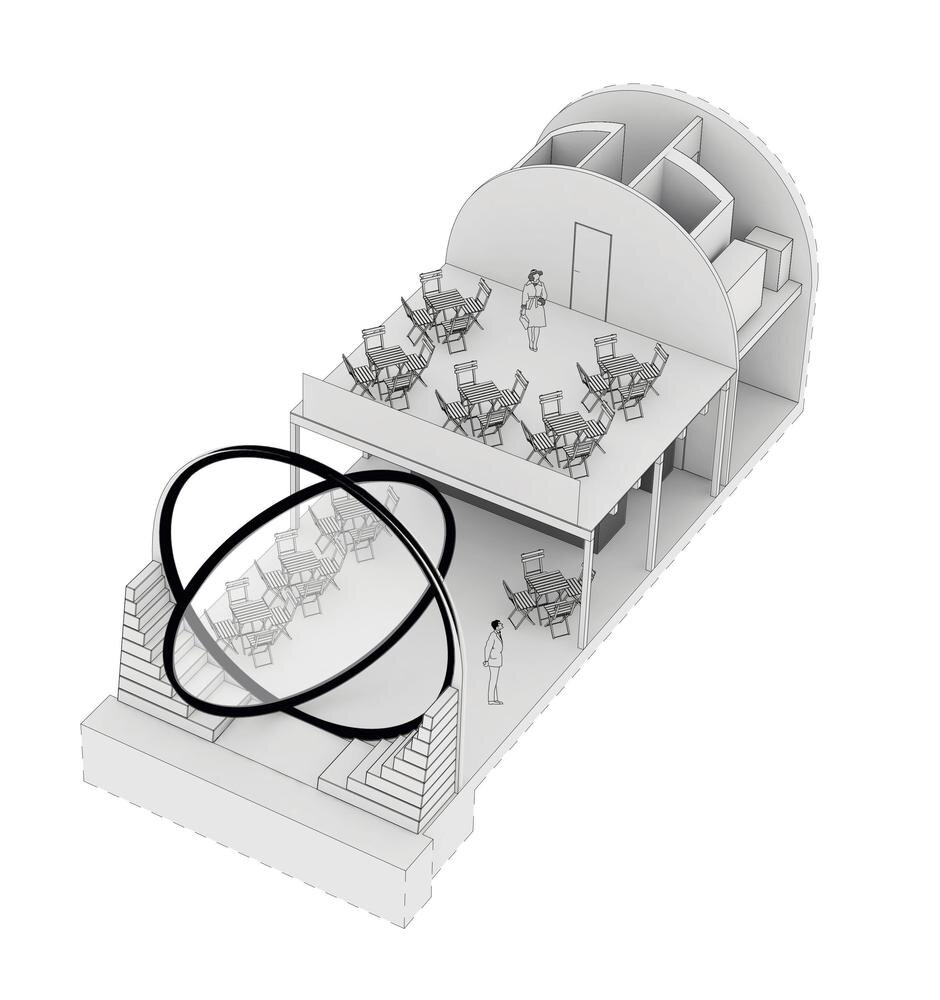

Sotto il viadotto (Under the viaduct)

© Agnese Samà, arch – G124

Notes

1 In the Master's program "Urban Mobility" of the Faculty of Urban Planning of the University of Architecture and Urbanism "Ion Mincu", methods and models of integrated planning UM (Urbanism and Mobility) are studied.

2 It revives the concept of "neighbourhood unit" proposed by Clarence Perry in 1923, emphasizing the need for spatial organization on the principle of proximity, with a preference for non-motorized movement between basic, everyday activities.