Locuri ale Națiunii

Places of the nation

| Să începem prin a defini noțiunea de „loc”.

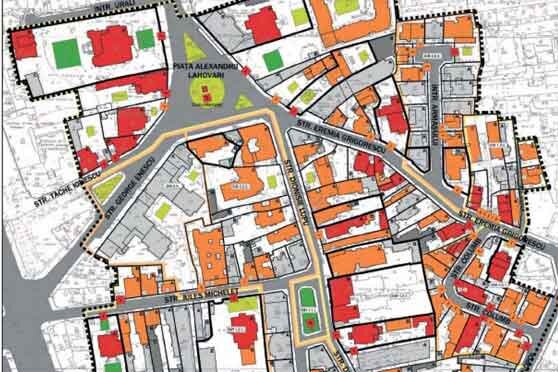

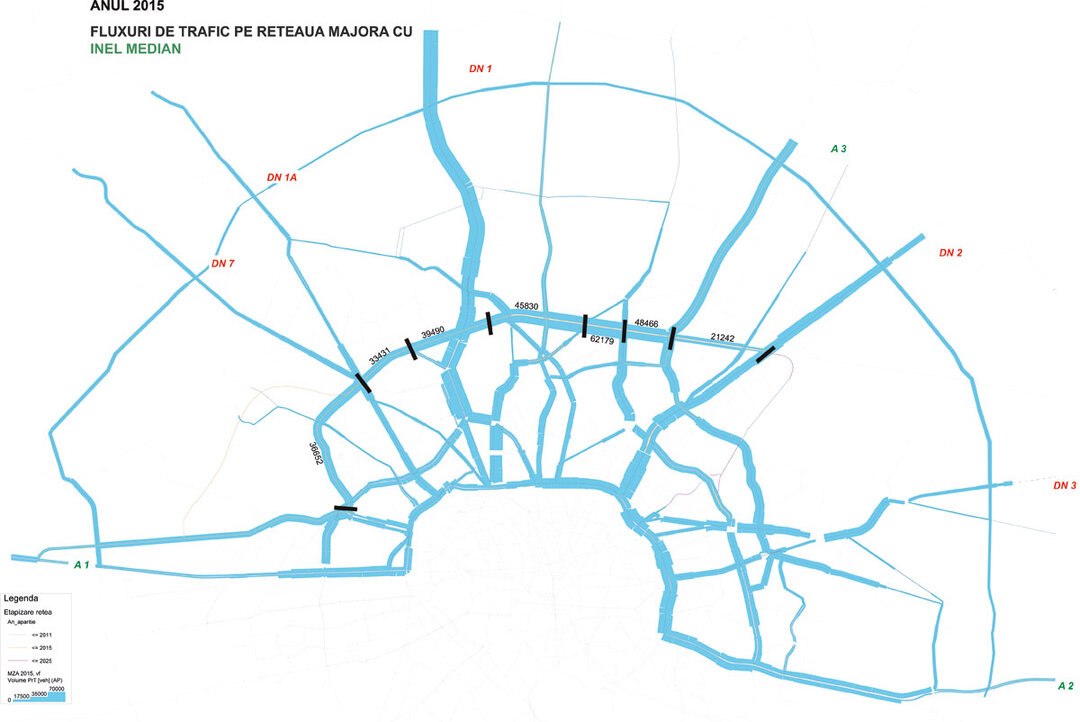

Probabil că argumentarea lui Heidegger este cea mai convingătoare: „... a locui înseamnă a exista pe Pământ”1. În același timp: „cuvântul din vechea germană pentru a construi / edifica BUAN (devenit BAUEN - n.n.) înseamnă și a locui”2. A locui este legat de „loc”. Pentru a da măsura exactă a acestei intime legături, Heidegger alege ca exemplu un pod. El unește malurile unui fluviu reunind în jurul lui pământurile ca regiune, dar mai ales: „... nu este podul care ocupă locul pentru a exista, ci numai începând cu podul se naște locul”.3 Cu o altă ocazie, Heidegger4 se referă la relațiile contextuale care leagă în lume ființele, lucrurile, natura. „Contextualismul” ca manieră de a privi proiectul arhitectural/urban sub forma unei medieri între existent și nou este teoretizat de Thomas Schumacher.5 Christian Norberg-Schulz aprofundează și dezvoltă. El scrie, în 1976, privind „locul”: „Noi înțelegem o totalitate de lucruri concrete având substanță materială, formă, textură și culoare. În același timp, aceste lucruri determină un «caracter environmental» care este esența legăturii. În general, un loc este resimțit ca un caracter sau o «atmosferă». Un loc este, deci, un fenomen calitativ «total» pe care nu putem să-l reducem la fiecare dintre proprietățile sale, precum relațiile spațiale, fără a pierde din vedere natura sa concretă”.6 Contextualismul, centrat pe noțiunea de „loc”, se consti-tuie (în numeroasele sale variante) ca o tendință teoretico-practică majoră în arhitectura ultimelor decenii. Nu putem, ajunși în acest punct, să nu evocăm ce am putea numi tendința opusă („arhitectura procesuală”, de „extrudere” a „congestiei”) care pretinde, în raport cu metropolizarea plane- tei, ieșirea din scară (Bigness), renunțarea la preocupările „formale” și contextuale, afirmând că: „«Arta» arhitecturii este inutilă în Bigness”.7 Pe ce teren teoretic ne vom situa deci în cazul abordării „locurilor națiunii” în București? Se poate vorbi de „locuri ale națiunii” acolo unde evenimente excepționale pentru destinul unor comunități au avut loc și s-au înscris în memoria colectivă. La Grütli, pe malul Lacului celor patru cantoane, a fost semnat, în 1291, Pactul perpetual, act fondator al Confederației elvețiene. De câmpia de la Blaj este legată configurația României moderne. În majoritatea cazurilor însă, „locurile națiunii” se găsesc pe teritoriul urban. Nu cred că este cazul să insist asupra rolului determinant pe care îl joacă arhitectura, deși surprizele sunt numeroase. Aș cita ca „locuri ale națiunii” în București: Dealul Mitropoliei, Piața Universității și „umbilicus urbis”, Piața Palatului. Voi expune aici numai câteva idei generale: - Locurile națiunii constituie „materializări” ale fundamentelor naționale. - Locurile națiunii merită să aibă o poziție prioritară în concepția de ansamblu și planificarea urbană. - Locurile națiunii sunt elemente structurale esențiale ale orașului contribuind de manieră determinantă la aprecierea și prestigiul acestuia. - Prezența lor printre preocupările permanente ale factorilor de decizie poate evita situații ca aceea a parkingului de sub Piața Universității, salvată in extremis prin intervenția arhitecților. - Intervențiile nu pot fi decât rezultatul unor concursuri de arhitectură minuțios pregătite, antrenând o largă participare, sub o jurizare incontestabilă. - Locuri de memorie, locurile națiunii pot fi în același timp: vii, atrăgătoare, conviviale, deschise unor multitudini de activități, scene capabile să răspundă celor mai exigenți creatori de „atmosfere”. - În fine, formula „bigness” nu pare - până la proba contrarie - cea mai apropiată celor trei situații bucureștene. |

| 1. Martin Heidegger - BÂTIR, HABITER, PENSER în:

„Essais et conférences”, Gallimard, Paris, 1958, p. 174 (trad. N.L.) 2. Ibidem 1, p. 172 (trad. N.L.) 3. Ibidem 1, p. 183 (trad. N.L.) 4. Martin Heidegger - L’ORIGINE DE L’OEUVRE DE L’ART în: „Chemins qui ne mènent nulle part”, Gallimard, Paris, 1962 5. Thomas Schumacher - CONTEXTUALISM: URBAN IDEALS AND DEFORMATION, Casabella nr. 359-360, 1971 6. Christian Norberg-Schulz - THE PHENOMENON OF PLACE în: „Designing cities”, editat de Alexander R. Cuthbert, Blackwell Publising Ldt. 2003, p. 116 (trad. N.L.) 7. Rem Koolhass - FIN DE SIECLE INNOCENTE? în Jaques Lacan, „OMA - Rem Koolhass. Pour une culture de la congestion”, Electa Moniteur, Paris, 1990, p. 114-115 (trad. N.L.)Places of the nation |

| Let us begin by defining the notion of “place”.

Heidegger’s argument is probably the most convincing: “dwelling” means “the stay of mortals on the earth 1.” Moreover: “The Old High German word for building, buan, means to dwell2.” To dwell is connected to “place”. In order to convey the exact sense of this intrinsic link, Heidegger chooses the bridge as an example. The bridge joins the banks of a river, gathering the earth as landscape around the stream, and above all: “the bridge does not come to a locale to stand in it; rather, a locale comes into existence only by virtue of the bridge 3.” Elsewhere, Heidegger refers to the contextual relations that bind together beings, things and nature in the world 4. “Contextualism” as a way of looking at architectural/urban design in the form of a mediation between the existent and the new is theorised by Thomas Schumacher 5. Christian Norberg-Schulz takes this idea further. In 1976, he wrote of “place”: „We mean a totality made up of concrete things having material substance, shape, texture and colour. Together these things determine an “environmental character”, which is the essence of place. In general a place is given as such a character or “atmosphere”. A place is there-fore a qualitative, “total” phenomenon, which we cannot reduce to any of its properties, such as spatial relationships, without losing its concrete nature out of sight” 6. Centred on the notion of “place”, contextualism, in its numerous variants, constitutes a major theoretical/practical trend in the architecture of the last few decades. Having come thus far, we cannot but evoke what we might name the opposite trend (“processual architecture”, the ar-chitecture of “extrusion” of “congestion”), which, in relation to the metropolisation of the planet, puts forward Bigness, an abandonment of “formal” and contextual concerns, arguing that “the ‘art’ of architecture is redundant in Bigness” 7. Therefore, in Bucharest, what theoretical ground do we occupy in the case of the “places of the nation” approach? It is possible to speak of “places of the nation” as those where outstanding events in the destiny of a community have taken place and inscribed themselves in the collective memory. In Grütli, on the shore of the lake of the four cantons, the Perpetual Pact was signed in 1291, the founding act of the Swiss Confederacy. The field at Blaj is linked to the coming together of modern Romania. In the majority of cases, however, the “places of the nation” are located on urban ground. I do not think that here is the place to dwell upon the decisive rôle played by architecture, although the surprises here are many. As “places of the nation” in Bucharest I would cite the Hill of the Metropolia, University Square and the “umbilicus urbis”, Palace Square. In the hope that I shall have the opportunity to develop this subject further in a future issue, I shall for the time being lay out a few general ideas: - The places of the nation are “materialisations” of what underlies the nation; - The places of the nation deserve to hold a position of prio-rity in the overall urban concept and in town planning; - The places of the nation are essential structural elements of the city, contributing in a decisive way to the its prestige and the way it is viewed; - If the places of the nation were among the ongoing concerns of decision makers, then situations such as the car park below University Square, which was rescued at the last moment thanks to the intervention of architects, might be avoided; - Such interventions must be only the result of painsta-kingly prepared architectural competitions with a wide range of entrants and an uncontroversial jury; - As sites of national memory, the places of the nation can also be lively, attractive, convivial, open to multiple activities, stages capable of responding to the most exigent creators of “atmosphere”; - Finally, until proven otherwise, “bigness” does not appear to be the most appropriate solution for the three situations in Bucharest. |

| 1. Martin Heidegger, “Building, Dwelling, Thinking”, in Basic Writings, Ed. David Farrell Krell, HarperCollins, London, 2008, p. 351.2. Ibid, p. 348.

3. Ibid, p. 356. 4. Martin Heidegger, “L’Origine de l’oeuvre de l’art” in Chemins qui ne mènent nulle part, Gallimard, Paris, 1962. 5. Thomas Schumacher, “Contextualism: Urban Ideals and Deformation”, Casabella nos. 359-360, 1971 6. Christian Norberg-Schulz, “The Phenomenon of Place” in Designing Cities, ed. Alexander R. Cuthbert, Blackwell, 2003, p. 116. 7. Rem Koolhass, “Fin de siècle innocente” in Jaques Lacan, OMA - Rem Koolhass. Pour une culture de la congestion, Electa Moniteur, Paris, 1990, pp. 114-115. |