Orașul arlechin

Arlequin city

| Spiritul unei urbe nu se relevă la prima privire; o lectură decantată, oglindită de planuri iscusit întrepătrunse, este necesară. Alteori, lectura urbană este doar un exercițiu plicticos, pentru cunoscători. Genius loci se manifestă uneori cu pregnantă claritate - splendoarea Parisului, vivacitatea Barcelonei, convenționalismul rafinat al Vienei - alteori genius se exprima difuz, texturat, alambicat, aproape labirintic - Marsilia, Istanbul, Praga, Alger - iscând niveluri de expresie pe măsura locului care îl invocă. |

| Cu fiecare oraș, un potențial arhetipal devine manifest. El generează forme și spații care, în diversitatea și comuniunea lor, prin multiplicitate și particularizări, exprimă mereu, inepuizabil, acea forță producătoare de cultură urbană, forță fără nume și fără chip.

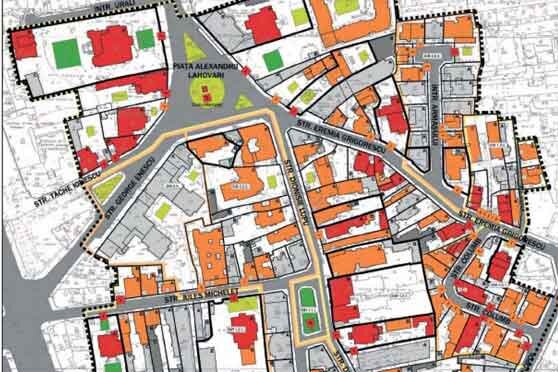

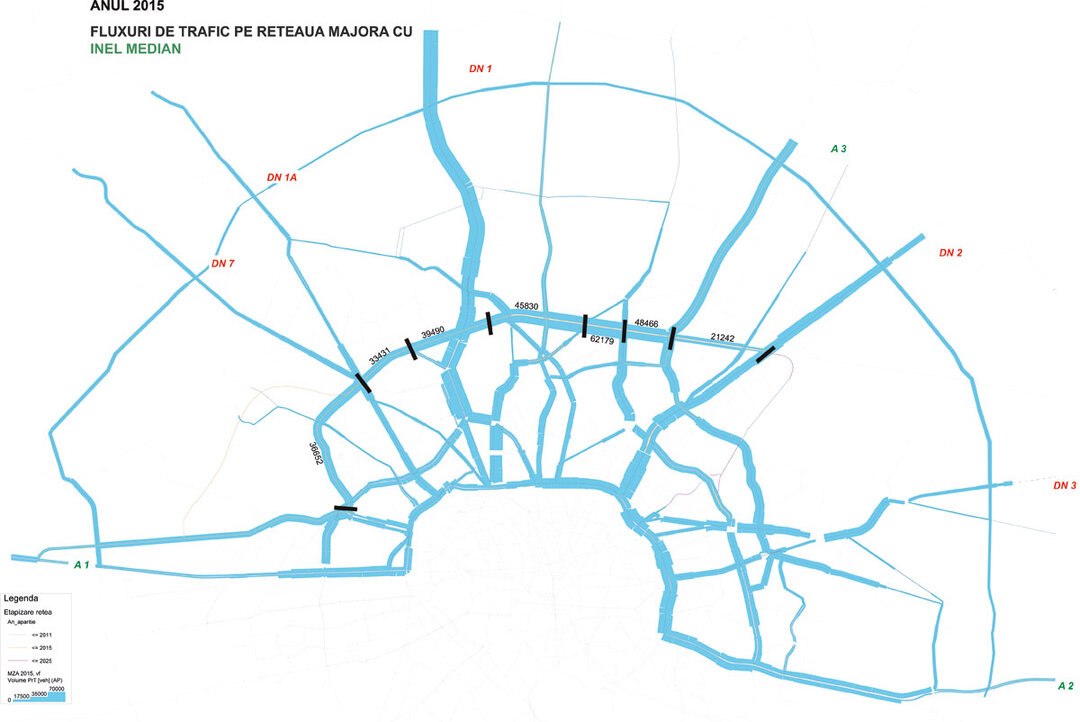

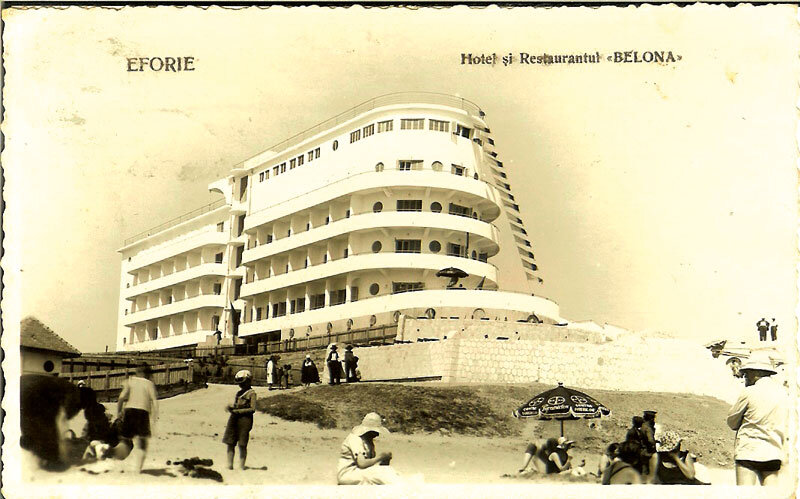

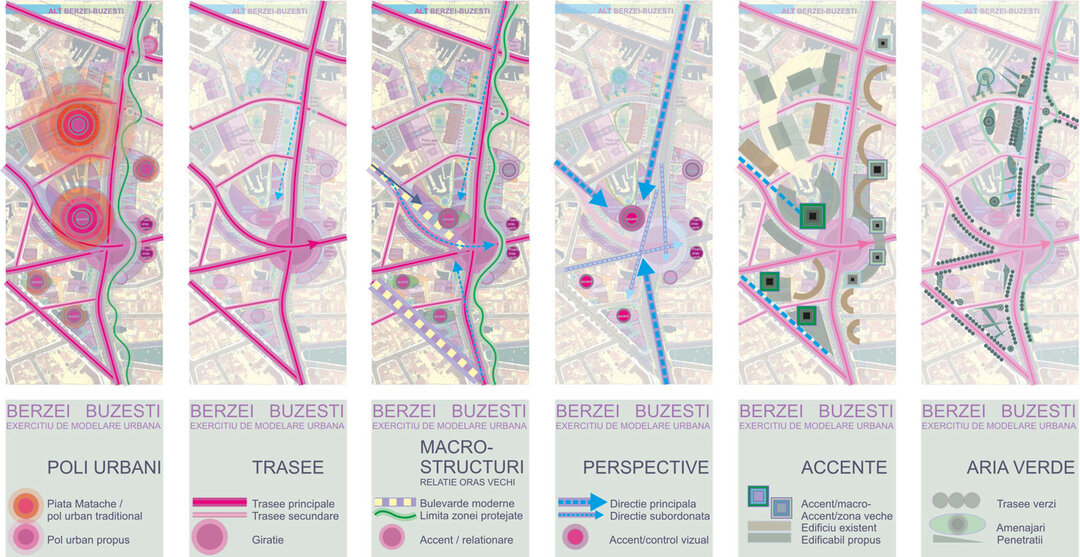

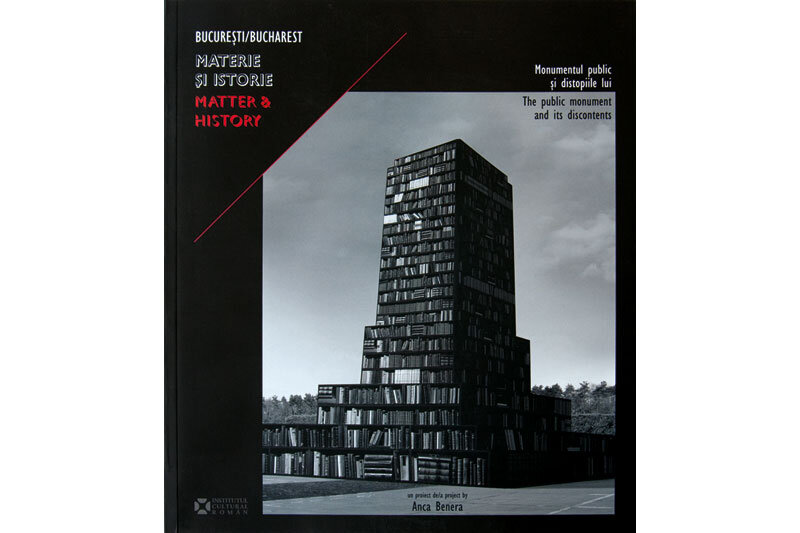

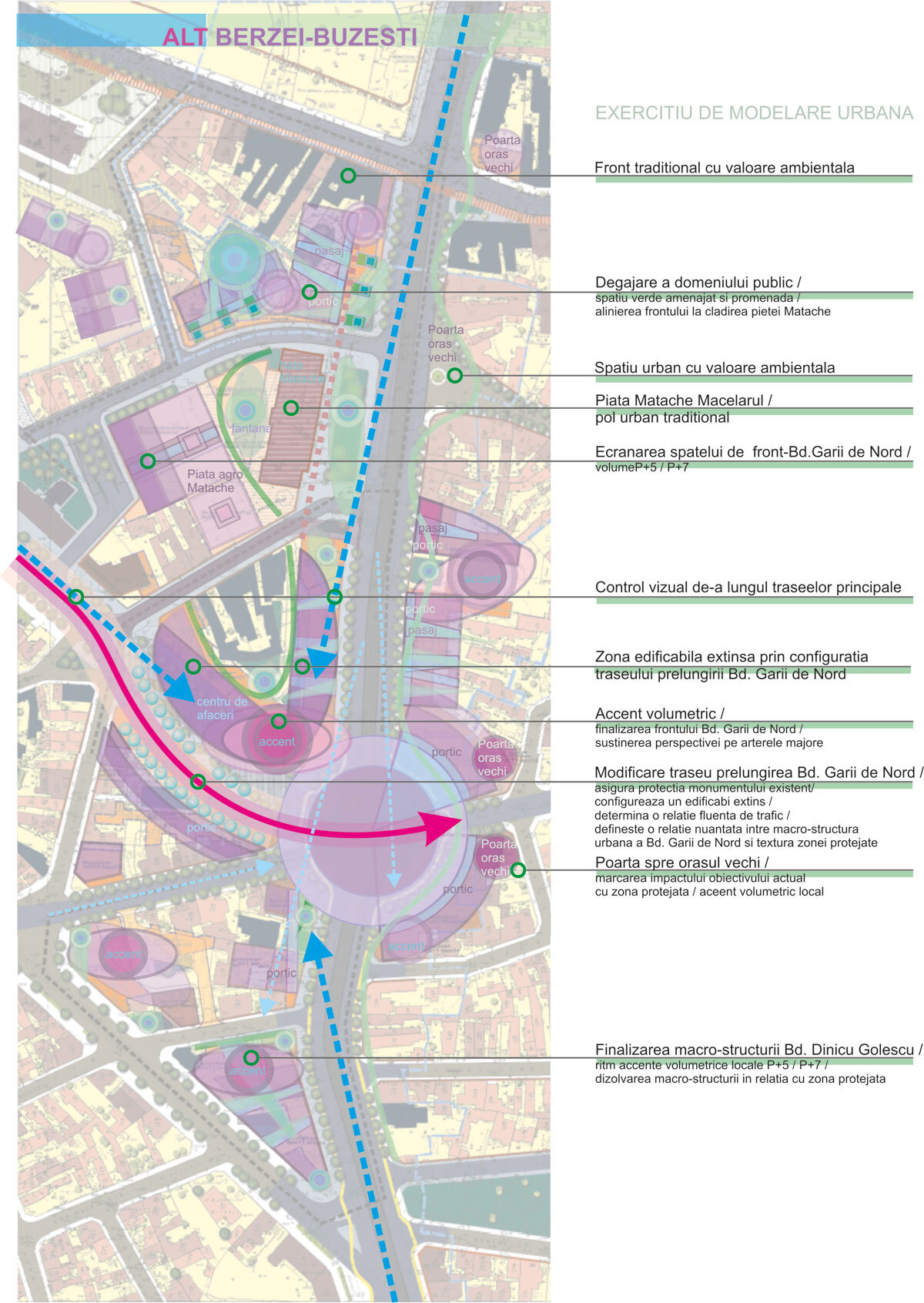

Arhetipul, generator și generic, este el însuși alegoric prezent în istoria orașului, ca o perma-nentă sursă de energie înnoitoare. În această dispoziție, privind spre București, ce vedem? Vedem, mai întâi, nevoia blajină a ciobanului Bucur de a-și adăpa oile. Ce frumos sună „salba de lacuri a Bucureștiului”! Salba frumoasă o vezi numai pe Bing Maps. Cu excepția Lacului Herăstrău și a Parcului Floreasca, avem un ștrand plin de nație romă la Tei-Toboc, sediul Grivco la Străulești, o bază sportivă fără clienți la Lacul Grivița, un rezidual „spontan și eteroclit” la Lacul Fundeni. Doi galbeni și parale de tinichea - o minune de salbă! Dâmbovița, „apă dulce” pe vremuri, când malurile ei erau umbrite de sălcii pletoase, este în prezent un canal navigabil fără navigație, poluat și neamenajat. Un fel de nepotrivire între poten-țial și putință ne aduce în minte fragmentarul hilar al arlechinului. Apoi vedem cum începe să grăiască istoria: Curtea Veche, Centrul Vechi, despre care s-a scris mult și încă se va scrie. Vedem cum din istoria Podului Mogo-șoaiei, a domeniilor boierești și a maidanelor se naște istoria mai nouă, a bulevardelor și a clădirilor decorate, a rezidențialelor opulente. Vedem cum neoromânescul flirtează cu stilul cubist. Vedem cum burghezul bucureștean a știut să ridice și clădiri prestigioase și reședințe confortabile într-o relație reverențioasă cu spațiul public al orașului și cum, uneori, distilează, din cotloane și detalii, un parfum inconfundabil. În imaginea orașului, interbelicul este singurul fragmentar măiestrit, un mozaic prețios și plin de grație. Apoi vedem istoria elanului socialist, despre care abia acum începe să se scrie. Vedem melanco-lia uniformizantă, domestic comercială a marilor cartiere în contrast de-a dreptul arlechines cu propaganda radioasă a „epocii de aur”, cu festi-vismul frust al defilărilor. Apoi vedem cum crește fiara dictaturii, care a devorat din oraș cât a putut. Mai întâi a creat cel mai alienant urbanism - urbanismul bulevardelor de cartier flancate cu blocuri, intersectându-se în girații flancate cu blocuri. A exaltat „la față” bunăstarea la preț redus și a surghiunit „la dos” cultura urbană tradițională. Este epoca rupturii prin excelență, a peticirii ru-șinoase a „vechiului”, mutilat și hărțuit, cu plasturii indecenți ai unei noutăți informe. Încă de pe atunci, arlechinul investit cu puteri arhetipale era prezent. Apoi dezastrul. Bucureștiul trăiește mai mult din traume decât din istoria lui bună. Puterea de nestăvilit a arhetipului creează și re-creează situația care l-a generat. Se pare că arhetipul Bucureștiului s-a configurat recent, la marile de-molări, din moment ce spiritul lor dăinuie. Nu face obiectul demersului meu oportunitatea operației urbane Berzei - Buzești, de ultima actualitate și în detaliu descrisă anterior. Altceva mă preocupă: dublarea diametralei nord-sud, un refren vechi de peste 30 de ani, în ultimii 20 de ani (postdecembrist, adică) a fost tratată ca un proiect de campanie electorală. În ciuda justificării lor structurale, nimeni nu mai credea în operații urbane mari, când cele mai mici, private și în general speculative, se dovedeau mănoase. Iată că apare, ca prin farmec, actorul politic cu poten-țialul acestei realizări. Întrebarea simplă este: ai, ca urbanist, șansa unei mari operații urbane. Așa o rezolvi? În buna tradiție a anilor ’80, care au dat ultima „schiță de sistematizare” a Bucureștiului și alte amintiri de neuitat? Procedeul urbanistic autohton prin excelență este „copy-paste”. Ne copiem narcisic pe noi înșine în ce avem mai prost. Sigur, exigențele de trafic pe noua diametrală la intersecție cu prelungirea Bulevardului Gării de Nord necesită o girație. Dar câte lucruri erau de rezolvat în zona acestei girații, în afara problemei evidente a traficului? Realizatorul PUZ-ului nu prezintă interes - în spatele unui executant sunt mereu consilieri profesionali. Aceasta este opinia Domniilor-Lor referitor la rezolvarea impactului unei intervenții urbane majore cu textura tradițională istorică a Bucureștiului, într-o zonă care implică o lungă listă de criterii și exigențe? Un traseu oblu, pentru economie de efort mental, când o lejeră inflexiune a traseului prelungirii Bd. Gării de Nord ar fi permis o relație mai nuanțată cu traseul de tip tradițional al străzii, ar fi permis controlul perspectivei pe noua arteră, o mai bună organizare a edificabilului și protecția convenabilă a unei case monument. O rezolvare exemplară a fronturilor în girație, roată frumos - nu deschideri de perspectivă, nu compoziție, nu control vizual. Mai interesant este compusă Piața Chibrit. Nu mai este la modă heat-ul „aici ar fi nimerit, pentru susținerea perspectivei, un accent de cel puțin 20 de niveluri”. Acum e la modă să fii la scara locului. Dar de ce și plicticos. Să nu-mi spuneți că plictiseala emană din limbajul sintetic al expresiei urbane, că nu vă cred. Până la arhitectura „de calitate” care să mobileze noile spații urbane, matricea urbanistică propusă, departe de a fi minimalistă, este de-a dreptul săracă. Edificabilul e otova, ocupă cu oroare de vid tot locul, cu lipituri la calcane care vor genera spații sordide, reziduale. Orice analiză de sit, oricât de erudită, se desfășoară pe un canal urban suprapus cu indiferență peste mădularele orașului. Ca Transamazonia prin pădurea virgină. Sperăm că studiul de impact promis post-factum ne va prezenta modul în care toate spațiile riverane cu valențe culturale au șansă de comunicare cu noua diametrală Berzei-Buzești. Nu sunt dintre nostalgici. Am încredere că se poate interveni actual și cu decență pe orice tip de țesut istoric constituit. Cu două condiții: profesionalism și bun-simț. Cu prima parte mulți stau bine, cu a doua stau mai prost. Numeroase clădiri cu o excelentă prezență arhitecturală sunt mastodonți urbani, ignoranți și ne-simtiți. Și mai am o bănuială: că marea excitație patrimonială legată de zona în cauză ascunde prost incapacitatea profesioniștilor de a crea valori actuale, cu un demers cultural mai amplu decât tradiționalul „dă bine”. În istoria lui recentă, Bucureștiul a zămislit o rasă urbană plebee. Vedem, cu regret, cum ea se multiplică fără jenă, cu vigoare primitivă. În locurile și casele care se duc, bucureșteanul sensibil caută un rest de demnitate, fie și mic-burgheză, demnitate care acum i se refuză. Nu din clișee, nu din automatisme și rutină, Genius loci va da naștere unor spații urbane purtătoare de cultură. În 2006, a fost supusă dezbaterii o primă variantă „așezată” a tronsonului nord al diametralei Brezei - Buzești. Soluția era remarcabilă pentru tratarea superficială. Sigur, monumentele de pe traseu erau frumos colorate (cu un negru funerar), iar peste ele trecea inocent diametrala. Nicio schiță de reglementare, nicio soluție alternativă pentru conservarea patrimoniului construit. Nici măcar cât să se poată vedea că sunt preferabile stră-mutările sau reconstrucția. Cineva râde cu poftă de tot ce am scris: arlechinul cu straiul lui indecent și peticit. Arlechinul atotputernic. Atotputernic pentru că știe că va reveni și cu alte ocazii oferite de limba de lemn și creierul de beton. Din 2006 până în 2011, oare nu se puteau aprofunda problemele zonei Berzei - Buzești nici măcar cu o grupă de la Master, cât să nu se preia „copy-paste” schița de sistematizare din anii ’80? Până primesc un răspuns, merg să fac o plimbare. Pornesc prin Parcul Ioanid, trec apoi prin Grădină Icoanei spre scuarul Bisericii Anglica-ne. Mă bucur de fântână cu statuia ei incredibilă, feminină și războinică. Trec agale pe strada Pictor Verona, apoi trec de Ateneu, spre statuia lui Carol I. Pe drum o să cuget de ce la noi teoria susține cu eleganță lucruri bine făcute numai la alții. |

| The spirit of a city reveals itself to us at first sight; a decanted reading, mirrored by skilfully interwoven planes, is required. At other times, an urban reading is merely a tedious exercise for the cognoscenti. The Genius loci sometimes manifests itself with meaning-laden clarity – the splendour of Paris, the liveliness of Barcelona, the refined conventionalism of Vienna. Sometimes it expresses itself diffusely, in a textured, convoluted, almost labyrinthine way – Marseilles, Istanbul, Prague, Alger – giving rise to levels of expression to fit the place that it invokes. |

| In every city an archetypal potential becomes manifest. It generates forms and spaces which, in their diversity and communion together, through their multiplicity and individualisations, constantly, inexhaustibly express the creative power of urban culture, a power without a name or face. Generator and generic, the archetype is itself allegorically present in the history of the city as a constant course of renewing energy.When we look at Bucharest in this mood, what do we see?

First of all we see the placid need of Bucur the shepherd looking for a place to water his sheep. What a wonderful expression: “Bucharest’s necklace of lakes”. You can see the beautiful necklace only on Bing Maps. Apart from Herăstrău Lake and Floreasca Park, we have a lido swarming with lowlife at Tei-Toboc, the Grivco headquarters at Străulești, a deserted sports facility at Grivița Lake, and a “spontaneous and heteroclite” residue at Lake Fundeni. Two gold coins and worthless coppers – what a wonderful necklace! The Dâmbovița, the “sweet water” of olden days, when its banks were shaded by weeping willows, is now a navigable canal without traffic, a polluted and abandoned waterway. The mismatch between the potential and the possible brings to mind the hilarious fragmentariness of the harlequin. Then we see how history begins to speak: the Old Court, the Old Centre, of which so much has been written. We see how from the history of the early days, of the Mogoșoaia Deck and boyar domains, the newer history of the boulevards, ornate buildings and opulent residences is born. We see how the Neo-Romanian style flirts with cubism. We see how the Bucharest bourgeoisie were able to construct prestigious buildings and comfortable residences for themselves in reverent harmony with the city’s public spaces and how in nooks and details they distilled an unmistakable perfume. In the image of the city, the inter-war period is the sole masterly fragment, a precious, graceful mosaic. Then we see the history of socialist élan, whose history is only now beginning to be written. We see the melancholy, uniform drabness of the large housing estates in harlequinesque contrast with the radiant propaganda of the “golden age” and the rudimentary festivity of the parades. Then we see how the monster of the dictatorship grows, devouring as much of the city as it could. Firstly, it created the most alienating urbanism possible: an urbanism of boulevards flanked by housing blocks, intersecting at roundabouts flanked by blocks. It exalted cut-price prosperity “on the face of it” and exiled traditional urban culture “around the back.” It is the epoch of rupture par excellence, of shameful patching of the tattered fabric of the old with the indecent plaster of an amorphous new. Back then, the harlequin imbued with archetypal powers was still present. Then came the disaster. Bucharest feeds on its traumas more than its positive history. The unstoppable power of the archetype creates and recreates the situation that generated it. It seems that Bucharest’s archetype was configured recently, during the great demolitions, given that their spirit persists. My present object is not the opportuneness of the Berzei-Buzești operation, which is of the utmost topicality and has been described in detail previously. What I am concerned with is something else: the north-site through route, a more than thirty-year-old refrain, has in the last twenty years (i.e. since the Revolution) been treated as an electoral campaign project. In spite of their structural justification, nobody believed in major urban projects any longer, when smaller, private and generally speculative investments proved handier. But lo and behold, as if by magic, the politician with the potential to achieve it has appeared. Is this the way to solve things? In the tradition of the 1980s, which gave Bucharest its last “systematisation plan” and other unforgettable memories? The native way of doing urbanism is the “copy-paste” method. We narcissistically copy all that is worst from our past. Obviously, the exigencies of traffic along the new through route at the intersection with the extension of Gara de Nord Boulevard required a roundabout. But how many other problems were there to solve apart from this roundabout, apart from the obvious problem of traffic? It isn’t important who created the Urban Zoning Plan. Behind the executor there are always professional advisers. Is this their opinion with regard to solving the impact of a major urban intervention on the traditional historical fabric of Bucharest, in an area that implies a long list of criteria and exigencies? A straight-line route, to save mental effort, when a slight flexion in the course of the extension of Gara de Nord Boulevard would have allowed a more nuanced relationship with the traditional course of the street; it would have given control over the perspectives of the proposed new thoroughfare, and would have allowed better organisation of the built fabric and protection of historic monuments. An exemplary solution for the frontages in the gyre, a beautiful wheel. There are no openings in the perspectives, no composition, no visual control. Even Piața Chibrit is more interesting. It’s no longer fashionable to say “an accent of at least twenty storeys would have been appropriate here to bolster the perspective”. Nowadays it’s fashionable to be in scale with the site. But why be boring? Don’t tell me that the boredom emanates from the synthetic language of urban expression, because I won’t believe you. As far as “quality” architecture to mobilise new urban spaces is concerned, the proposed urban matrix, far from being minimalist, is downright impoverished. The built fabric is uniform, it fills the entire space with a horror vacui, with patched-up blind walls, which will create wretched, residual spaces No matter how eruditely you analyse the site, it runs along an urban channel nonchalantly superimposed upon the innards of the city, like the Trans-Amazonia through virgin forest. We hope that the promised post-factum impact study will present the way in which all the adjacent spaces of cultural value will be able to communicate with the new Berzei-Buzești through route. I’m not one to be nostalgic. I believe that it is possible within any type of historical built fabric to make interventions that are up-to-date and decent. On two conditions: professionalism and common sense. Many people possess the former but lack the latter. Numerous buildings with an excellent architectural presence are ignorant, boorish urban mastodons. I also suspect that the great heritage excitement linked to the area in question poorly conceals on the part of the professionals the incapacity to create up-to-date values, using a cultural approach wider-ranging than the traditional “it looks good”. In its recent history, Bucharest engendered a plebeian urban species. We see with regret how it multiplies unabashed, with primitive vigour. In the places and buildings that are on the way out, the sensitive resident of Bucharest seeks a remnant of dignity, even if it is a petit-bourgeois dignity, a dignity that is now denied to him. It is not from clichés, automatic reflexes and routine that the Genius loci will give birth to new culture-bearing urban spaces. In 2006, an initial, “settled” version of the northern segment of the Berzei-Buzești through route was presented for debate. The solution was remarkable for its superficiality. Of course, the monuments along the route were nicely coloured in (using funereal black), and above them innocently passed the through route. There was no alternative solution for conservation of the built heritage, not even enough to make it visible whether it was preferable to move or to reconstruct the buildings. Someone is chortling at what I have written here: the harlequin in his garish, patched garments. The all-powerful harlequin. All-powerful because he knows he will be back when other opportunities provided by wooden tongue and concrete brain present themselves. From 2006 to 2011, was it really not possible to study the problems of the Berzei-Buzești area more closely, so as not to copy and paste the systematisation plan of the 1980s? While I’m waiting for an answer, I’m going to take a walk. I set out through Ioanid Park, and then I cross Icoanei Garden, in the direction of the Anglican Church. I stop to admire the fountain with its incredible, feminine, warrior statue. I quickly cross Pictor Verona Street and then head toward the Athenaeum and the statue of Carol I. On the way, I think about how in Romania theory elegantly supports things well done only elsewhere. |