Reprezentațional vs ontologic: despre o dilemă fără soluție

Representational vs ontological:

about a solution-less dilemma

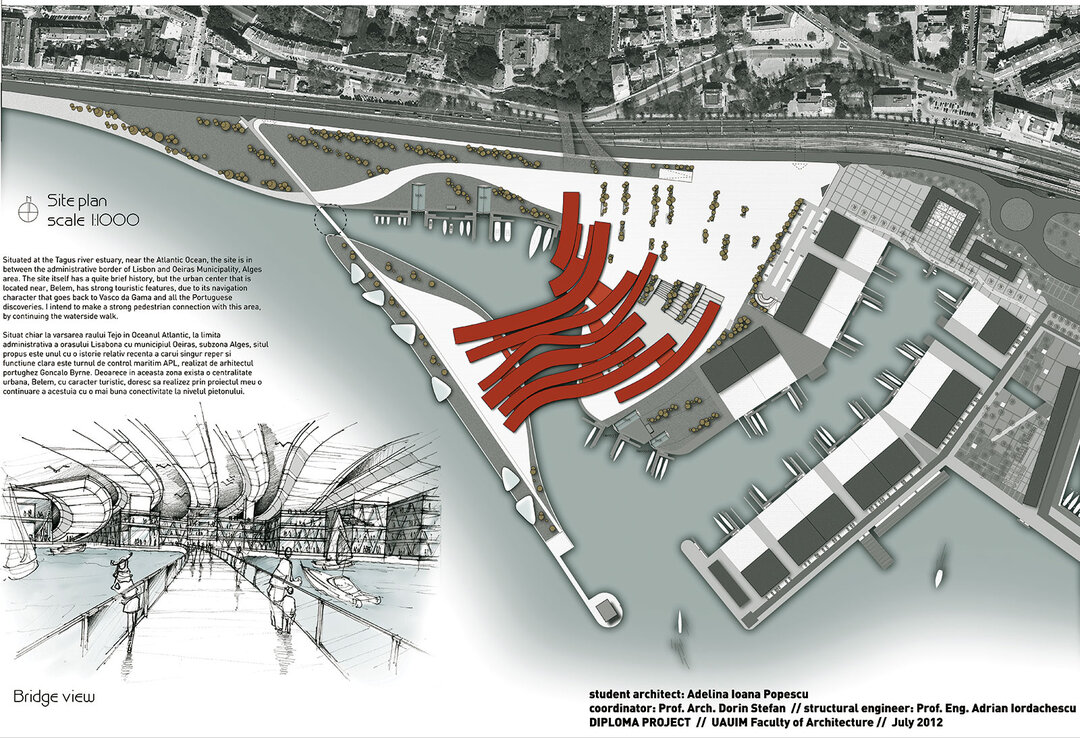

| Profesorul John E. Hancock, de la Universitatea din Cincinnati, Ohio, mi-a fost îndrumător în programul de MSArch pe care l-am terminat în 1993-’94. De data aceasta (2012), m-a luat partener în cadrul atelierului de proiectare de la anul 5 (an terminal la MA în arhitectură: diplome, adică).Am rămas cu mai multe idei interesante de la profesorul meu de-a lungul celor optsprezece ani de când ne cunoaștem și colaborăm. Dar, de data asta, m-a șocat refuzul său de a privi măcar la elevații:

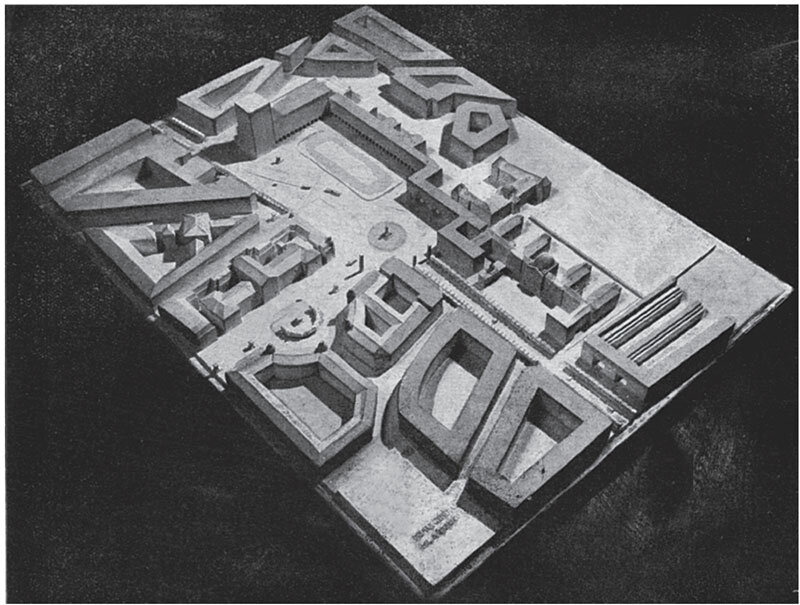

- Elevațiile mint. Aveți nevoie de ele în proiectele tehnice, desigur, dar sunt păgubitoare în procesul de proiectare. Ajutați-vă, când croiți spațiul și obiectul care-l conține și articulează, de machete de lucru, de secțiuni, de perspective virtuale și, dacă se poate, chiar de animație. Dar nu de elevații! |

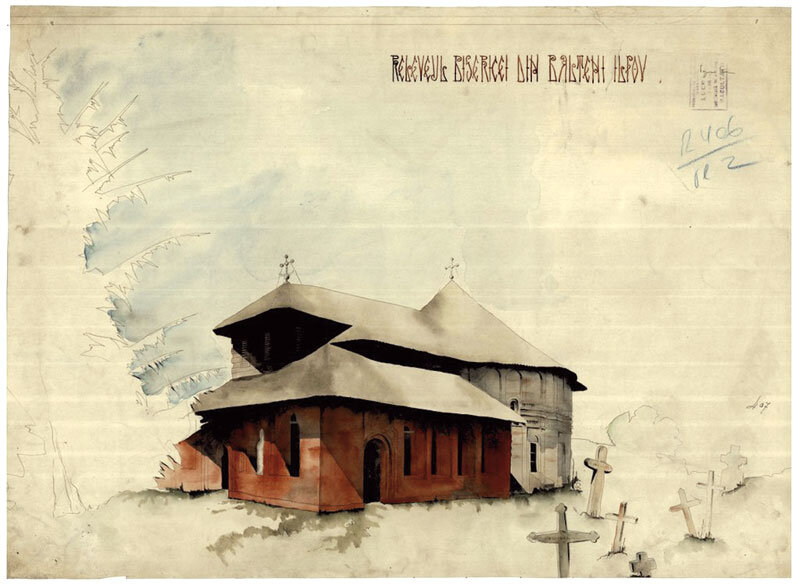

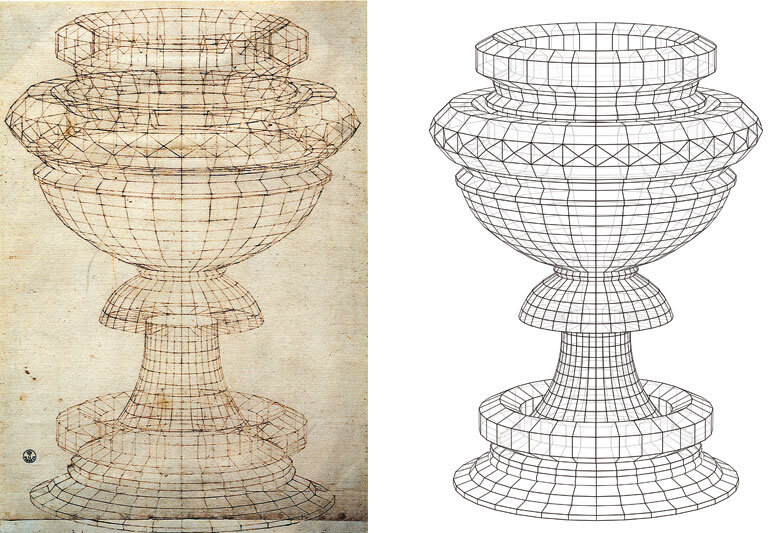

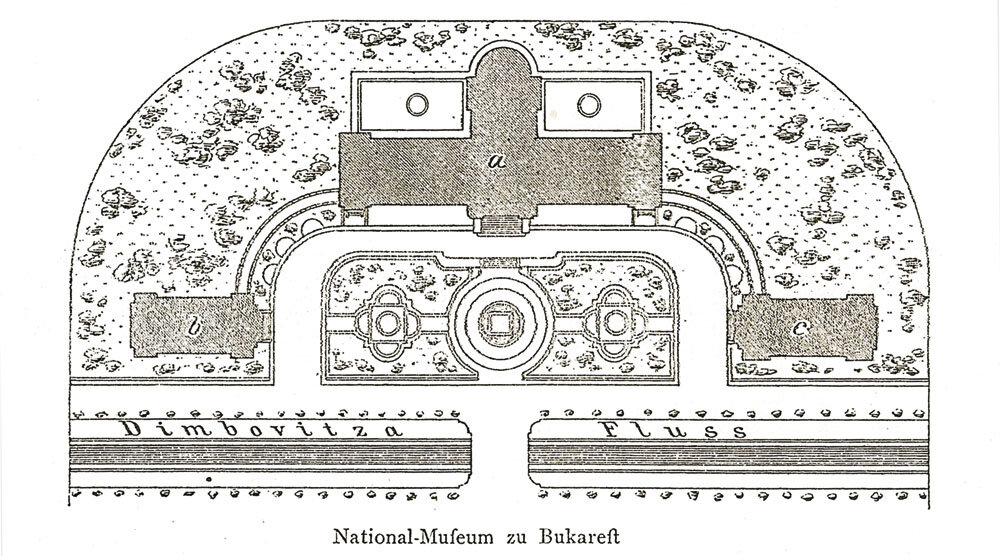

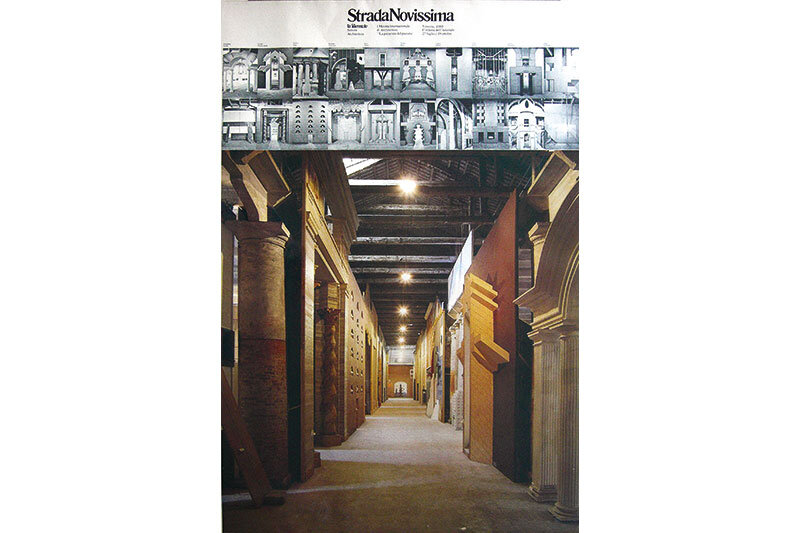

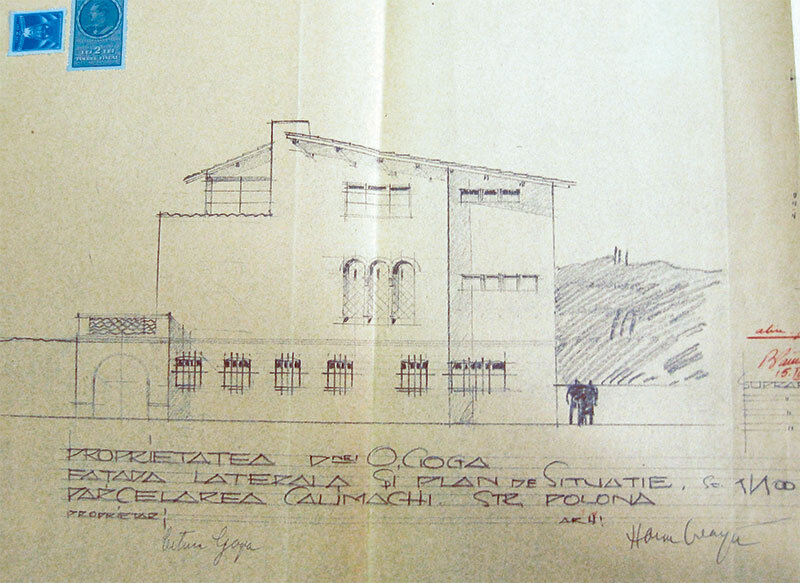

| Pentru a explica refuzul net al profesorului Hancock de a privi măcar elevațiile aduse de diplomații săi, trebuie să ne întoarcem puțin și să privim cu mare atenție la consecințele unui concept care ne vine din filosofie, dar a făcut carieră și în arte, mai ales în arhitectură: conceptul de reprezentare, care este secund în raport cu acela, încă și mai important, de prezență.Mi-am amintit că noi nu am învățat în școală decât despre descompunerea cutiei tridimensionale, cum numea acest procedeu de proiecție Bruno Zevi (dar am aflat despre nume abia când am publicat în colecția Spații Imaginate, a Editurii Paideia, traducerea cărții). Cu alte cuvinte, eram învățați nu să gândim obiecte și spații în concatenarea lor, ci să desenăm reprezentări elegante ale acestora pe pereții unor imaginare planuri de proiecție ortogonale. Ceea ce prezentam la corectură, ceea ce proiectam, erau reprezentări, nicidecum o ipotetică prezență, deocamdată virtuală, a unui obiect arhitectural. Discutam despre eleganța compunerii planurilor și a fațadelor în ortogonal, încredințați fiind că, dacă acestea sunt desăvârșite, cum altfel avea să fie obiectul ale căror reprezentări vor fi fost? În același timp, însă, priveam nedumeriți la planurile unor capodopere, care planuri numai echilibrate și bine compuse nu erau; or, cum era posibil, ne întrebam - nu toți - ca o capodoperă să nu aibă proiecții, reprezentări desăvârșite? La atelier, Alvar Aalto ar fi picat proiectul cu unele din planurile clădirilor sale.

De la edificiile deconstrucției înainte, de la proiectul câștigător la Hong Kong Peak Competition (Zaha Hadid) la casele numerotate ale lui Peter Eisenman, nu mai era, însă, nimic de înțeles nici pentru bieții noștri profesori, necum pentru studenții care eram. Nițică alinare mai găseam în planurile clasicizante ale cutăror edificii postmoderniste, a căror simetrie o pricepeam; dar a căror ironie superioară, bazată pe referințe culturale, ne scăpa, deși știam, de la profesorul nostru de estetică, Cezar Radu, despre opera aperta și „citatul cu funcție estetică”, de vreme ce era traducătorul în română al Tratatului de semiotică al lui Umberto Eco. Cât despre traseele regulatoare ale profesorului A. Gheorghiu, pe care nu l-am prins în viață ca student, le-am bănuit întotdeauna de idealism și de nițică exagerare: același Eco povestește, prin gura unui personaj din Pendulul lui Foucault, cum un excepțional egiptolog, Piazzy Smith, ar fi fost prins pilind colțul unei pietre de piramidă, ca să se încadreze măsurătoare în cutare proporție flatantă… Dar nici nu trebuia să ne ducem atât de departe, întrebările pluteau în aer și pe la noi: „Au cunoscut meșterii lui Constantin Brâncoveanu secretele piramidelor?”, se întreba, chiar în revista Arhitectura, Radu Drăgan. Ele reveneau, știam de la istoria arhitecturii și de la volutele templului Nike Apteros, pe care l-am desenat în anul I, ca multiplicare a unui modul cu referință umană. Știam, de la Vitruvius, că pot reprezenta întregul templu (acesta - pars pro toto - era o imagine a lumii) dacă pot „extrage simetriile” corpului uman (cum frumos spune traducerea românească, încă neegalată din nefericire, a lui Cantacuzino și Gr. Ionescu). Dar, de asemenea, știam că din aceste relații geometrice se nășteau și proiectele lui Richard Meier, pe care le vedeam la American Library, căci țineam cu tot dinadinsul să înțelegem cum se tocmește un proiect și profesorii pe care i-am avut la atelier nu puteau articula o explicație coerentă, sau n-aveau chef. |

| Citiți textul integral în nr 4/2012 al revistei Arhitectura. |

| Bibliografie și sugestii pentru lecturi viitoare

Alexander, Cristopher HOUSES GENERATED BY PATTERNS (with Sanford Hirshen, Sara Ishikawa, Christie Coffin and Shlomo Angel), Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, California, 1969. A PATTERN LANGUAGE WHICH GENERATES MULTI-SERVICE CENTERS (with Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein), Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, California, 1968. Burton, James „Notes from Volume Zero: Luis Kahn and the Language of God” in Perspecta I, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986, p. 69-90. Markus, Thomas A și Cameron, Deborah The words Between the Spaces: Buildings and Language, London/NY: Routledge, 2002. Eckler, James Language of Space and Form: Generative terms for architecture, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2012. Kausel, Lewis C. Design&Intuition: Structures, interios&the mind, Ashurst Lodge, Ashurst, Southhampton, UK: WIT Press, 2012. Ockman, Joan (Ed.) The Pragmatist Imagination: Thinking about „things in the making”, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000. Markus, Thomas A. și Cameron, Deborah The words Between the Spaces: Buildings and Language, London/NY: Routledge, 2002. Mateo, Josep Lluis et alii Iconoclastia: News from a post-iconic world, Architectural Press IV Series, Barcelona: ACTAR, 2009. Pressman, Andrew Desiging Architecture: The elements of process, London, NY: Routledge, 2012. Temple, Nicholas, and Bandyopadhyay, Soumyen (Eds) Thinking Practice: Reflections on architectural research and building work, Black Dog Publishing, 2008. |

| Professor John E. Hancock from Cincinnati University, Ohio, was my tutor during the MS Arch. programme that I completed in 1993-’94. This time (2012), he took me as partner in the 5thyear designing studio (final year in MA in architecture diplomas so to speak).For eighteen years that we know each other work and collaborate I retained a lot of interesting ideas from my teacher. But, this time, I was shocked by his rejection to even look at elevations:

- Elevations are lying. You need them in the technical projects, obviously, but there are misleading in the architectural design process. Whilst you shape the space and the object that contains and articulate it rely and use working models, sections, virtual perspectives and if possible even animations. But not elevations! |

| To explain professor’s Hancock rejection to even look at elevations brought by his diploma’s students we must turn back a little and look carefully at a concept originating from philosophy but that made carrier in the fine arts, mostly in architecture: the concept of representation, that is secondary in relation with the even more important one: that of presence. I remembered that we only learned in school about the tridimensional box unfolding, as Bruno Zevi named this method (but I found out about the name only when I published the book’s translation in the Imagined Spaces collection of PaideiaPrinting House). In other words we were taught not to think objects and spaces in their chaining, but to draw elegant representations of these over the walls of imagined plans belonging to an orthogonal projection. What we were presenting at reviews were representations, no question of hypothetic presence, for that time being a virtual one, of an architectural object. We were discussing on the elegance of plans and elevations composition in orthogonal, being reassured that - if these are well mastered the architectural object would have been alike its representations.Still, in the same time, we looked confused at the plans of some masterpieces that had no equilibrated plans nor well composed; how was it possible, we asked ourselves - not all of us - that a masterpiece has no flawless projections and representations? In the studio, Alvar Aalto would have failed the project with one of the plans of his buildings.

From prior deconstructivism buildings, from winning design in Hong Kong Peak Competition (Zaha Hadid) to the numbered houses of Peter Eisenman, for our poor professors there was nothing left to be understood, neither for us students that we were. Little comfort was to be found in the classic plans of some post-modern buildings, whom symmetry we perceived; but whom superior irony, based on cultural references, we were losing, although we knew, from our esthetic professor, Cezar Radu, about opera aperta and the “quotation with esthetic function”, because he was the Romanian translator of the Semiotics Treatise of Umberto Eco. As for the reglementing traces of professor A. Gheorghiu, that being student I did not catch alive, I always suspected them of idealism and a bit of exaggeration: the same Eco tells, through the voice of a Foucault Pendulum character, that an extraordinary Egyptologist, Piazzy Smith, would have been caught filling a pyramid stone, to conform measurement in such flattering proportion. But we should not have been getting that far, the questions were floating in the air even among us: „were Constantin Brâncoveanu kraftmen knew the secrets of the pyramids?“ was asking Radu Dragan in an Arhitectura issue. They were coming back, we knew from architecture’s history and from the capitel spirals of Nike Apteros temple, which we drew in the 1st year, as multiplication of a human reference module. We were aware, from Vitruvius, that could represent the entire temple (this - pars pro toto - was a world’s image) if they can “extract the symmetries” of human body (as very beautiful says the Romanian translation, yet unfortunately un evened, by Cantacuzino and Gr. Ionescu). But, in the same time, we knew that these geometrical relations were borne from Richard Meier’s projects, which we’ve seen in the American Library, because we wanted stubbornly to understand how a project is negotiated and the professors that we had at studio either could not articulate a coherent explanation or were not in the mood to. |

| Read the full text in the print magazine. |

| Bibliography and suggestions for further readings

Alexander, Cristopher HOUSES GENERATED BY PATTERNS (with Sanford Hirshen, Sara Ishikawa, Christie Coffin and Shlomo Angel), Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, California, 1969. A PATTERN LANGUAGE WHICH GENERATES MULTI-SERVICE CENTERS (with Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein), Center for Environmental Structure, Berkeley, California, 1968. Burton, James „Notes from Volume Zero: Luis Kahn and the Language of God” in Perspecta I, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986, p. 69-90. Markus, Thomas A and Cameron, Deborah The words Between the Spaces: Buildings and Language, London/NY: Routledge, 2002. Eckler, James Language of Space and Form: Generative terms for architecture, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2012. Kausel, Lewis C. Design & Intuition: Structures, interios & the mind, Ashurst Lodge, Ashurst, Southhampton, UK: WIT Press, 2012. Ockman, Joan (Ed.) The Pragmatist Imagination: Thinking about „things in the making”, NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000. Markus, Thomas A. and Cameron, Deborah The words Between the Spaces: Buildings and Language, London/NY: Routledge, 2002. Mateo, Josep Lluis and others Iconoclastia: News from a post-iconic world, Architectural Press IV Series, Barcelona: ACTAR, 2009. Pressman, Andrew Designing Architecture: The elements of process, London, NY: Routledge, 2012. Temple, Nicholas, and Bandyopadhyay, Soumyen (Eds) Thinking Practice: Reflections on architectural research and building work, Black Dog Publishing, 2008. |