Annotated file Buzești - Berzei - Uranus. Gruia Bădescu

Adrian Bălteanu: Please comment briefly on the articles about the implementation of the N-S Diametral N-S Doubling plan, published in the first issue of "Arhitectura" magazine.

Gruia Bădescu: The statements presented in the material show that, beyond the urban solution itself, the Buzești-Berzei case is problematic for the irregularities that have occurred in the implementation of the project, especially since these abuses come from the public sector. What is being said here highlights a worrying fact, a state in which the public sector abuses. For many years we have been talking about irregularities committed by certain actors in the private sector, breaches of regulations, etc. But now we are talking about the public sector itself, which is supposed to be looking after the public interest and the rule of law. The situation, as it emerges from this, expresses a deeper crisis than a simple urban planning decision - wrong or not - a crisis of the "public", the failure of the social contract based on trust and transparency.

A.B.: You have publicly stated that this intervention is inappropriate from an urban planning point of view. Could you explain this for our readers?

G.B.: The whole urban operation is based on the premise that the new Uranus Boulevard will help decongest traffic in the central area. That premise, however, is in obvious conflict with the axiom of urban transportation - more or wider roads mean more traffic. From the American cities of the 1950s and 1960s to today's Chinese cities, in all cases, the opening or widening of new roads has led to over-congestion. Why? Because a wider road creates an incentive for drivers. At a time interval that depends on the case, the new road will also be congested. I have heard many say that we cannot apply Western models that focus on human-centered urbanism, quality of public spaces and improved conditions for pedestrians and cyclists, because Bucharest does not yet have the infrastructure in place. That the Diametrale project has its origins in the interwar period and that now is the time to finalize it. That Bucharest is "different". That we will manage the situation better. But this is exactly what has been invoked every time, in every city, over the decades, until it has come to be regretted in every case. It is very unfortunate to invoke this 'exceptionalism' in order to pay huge sums of money for road infrastructure works, widening, suspended highways, etc., and then to find that traffic only gets worse. Some have adopted ultra-expensive solutions to escape the mistakes of the past (like Boston's Big Dig project, the most expensive urban project in history).

I am opposed not only to the specific situation of Berzei-Buzești, but to a model that can be repeated in other parts of the city or even in other cities in the country - widening boulevards in the name of traffic fluidity, which entails demolitions that become, by the axiom of urban transportation, unnecessary and avoidable. The names of areas such as Traian are already being bandied about as the next to be "remodeled" for a more car-friendly city.

Even though the Diametrala is not a highway, but is defined as a boulevard, it is nothing more than an artery that will have a lot of road space, which will invite cars. It is a false solution to a real problem in Bucharest, that of an urban mobility that has become difficult. The solution is not to widen roads or create new roads, but to facilitate alternative modes of transportation. Bucharest needs public transport that covers the city much better, that runs more frequently, dedicated bike lanes, pedestrian-friendly connections, and only then will people give up their cars. Just think of the success of tram 41, which comes and goes fast and is preferred by the very people who have a car in that area.

Bucharest has an opportunity now to learn from the mistakes of other cities in the past (or present - see China) and avoid costly investments that not only will not have the desired result, but also create additional problems. Car traffic creates an obstacle for the majority users of the city (let's not forget that only a minority of almost a quarter of Bucharest's population use cars). The stream of cars creates both a physical and a mental obstacle for people, a traffic boulevard becomes somewhat that "edge" that Kevin Lynch talked about in the well-known "The Image of the City".

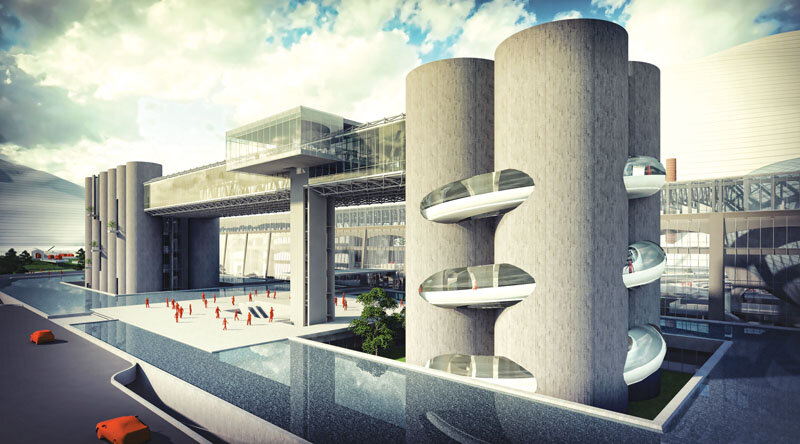

And lining such an avenue with compact fronts of tall buildings creates a second obstacle, a second screen. A new Potemkin village, creating the illusion of modernity while isolating the traditional fabric and built substance left behind. The boulevard and its tall buildings segment and segregate the old neighborhoods, acting as a screen, an obstacle to the natural flows of an area developed on an east-west, not north-south grid. Edging with blocks and screening are the hallmarks of the last communist decades in Bucharest, of the new Moșilor New Way, which hides, behind a row of blocks, traditional areas - Latină, Făinari, Foișorul de Foc - that become almost imperceptible from the radius of the boulevard or, most evocatively, the boulevards of the Civic Center, which hide isolated enclaves of traditional fabric. I wonder if this is the model of the new Bucharest, of a city that segregates, segments and enclaves islands of the old city, while other European cities are going for connectivity and accessibility at the local scale.

The human scale is what is lacking in this intervention, which remains tributary to a perishable mid-20th century urbanism. I think we can do more than that. First of all, we can analyze what theory and practice elsewhere offer us and not deny everything out of an exceptionalism that becomes damaging and repeats the mistakes and then repeats the regrets and the costly attempts to repair them. I have not even mentioned here the other aspects of the intervention - demolitions of heritage buildings, evictions, the resulting pollution and so on. These are all problems that result from a vision of the city that is very damaging and I think that this anachronistic idea of a city built around cars must be attacked, mainly.

A.B.: The need for the ring road was mainly argued by the need to ensure a quick connection between the north and the south of Bucharest, especially between the government and the parliament (in events such as NATO meetings) and by allocating parts of the roadway on streets such as Calea Victoriei, Calea Griviței, Bd. Magheru to pedestrians. How do you comment?

G.B.: The idea of giving pedestrians more space on streets such as Calea Victoriei is commendable, in my view. But so far I have not heard any guarantee that the widening of the sidewalks, for example, will be conditional on the completion of the Buzești-Berzei ring road project. The assumption is that, with the bypass, traffic will be decongested on Calea Victoriei. But, as I pointed out above, the diametral will just create another congested traffic artery next to Calea Victoriei, because it will act as a traffic stimulus. Experience in many cities has shown that if you close an artery or restrict traffic (narrower roadway, congestion charges, etc.), traffic will re-flow by itself, and by providing alternative means (rapid transit, dedicated lanes, bike lanes, pedestrian walkways), it will decrease. Just as an example, Peter Bishop, director of the London Development Agency, recounted how when a central bridge over the Thames was closed to cars, the effects on car traffic were imperceptible, despite initial fears. Drivers either rerouted or changed their mode of transportation. Likewise, I wonder if the Buzești-Berzei closure for the construction site has created that much of a traffic problem in the area these last few months... So I don't see a problem by simply redoing the pedestrian infrastructure of Via Victoriei or Via Griviței, without having to create extra lanes for cars elsewhere.

A.B.: What and how can be fixed now?

G.B.: If an urban project gets off to a bad start, that doesn't mean it has to continue or end badly. A good number of houses have already been expropriated and demolished, but that doesn't mean that the boulevard that will appear there cannot be "tamed", that it cannot have a distribution between the surface area for the roadway - public transport - bicycle lanes - sidewalks that is appropriate for a contemporary European city urban design, with priority for alternative means of transport, or that the new buildings cannot be anything other than monolithic office blocks that will act as a screen. Moreover, the whole area has both the social problems and built heritage that make it an ideal candidate for an integrated urban regeneration program in line with practices in all EU countries. As early as 2000, architecture students under the guidance of Hanna Derer have been thinking about such a regeneration opportunity, starting from the clear role of the Via Grivița as a gateway to the city centre. This is just one possible direction. In the interdisciplinary urban planning workshop București Alternativ, we brought together young architects, urban planners, sociologists and anthropologists to explore possibilities for regenerating the area. The idea was to show that it can be done differently, even in the current situation, with the demolitions already done, and to launch a real debate on the opportunities for regeneration in the area and on alternatives to projects that seem anachronistic to us. And I repeat, we do not only need a debate on Buzești-Berzei, but also on the role of the car in the Romanian city, on the issue of traffic arteries and highways in cities, on the issue of real urban regeneration, on the issue of prioritizing investments for the public good and a coherent and sustainable urban development.

Interview on June 10, 2011

Description

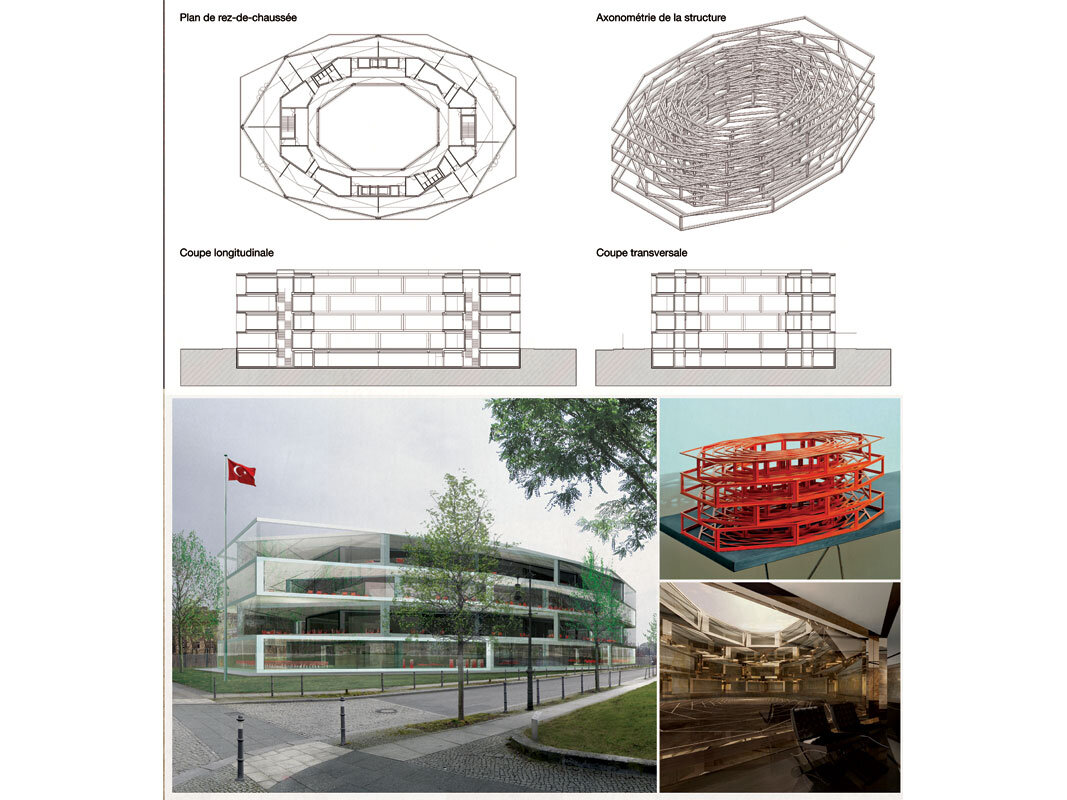

Gruia Bădescu is a graduate of the Masters in Urban Design of the Cities Programme at the London School of Economics and has worked as a practitioner and researcher in the field of urban design, urban regeneration and urban reconstruction in Romania, UK, Spain, Germany, Germany, Turkey, Lebanon, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Beginning with his undergraduate work at Middlebury College (USA) on the reconstruction of German cities after World War II, Bădescu has researched the phenomenon of the car-built city (die autogerechte Stadt), as well as ways of "reclaiming" the city through the reinvigoration of public spaces and human-scale urbanism. In the Romanian space, she has worked with Space Syntax on a series of projects on public space and urban regeneration.