Annotated file Buzești - Berzei - Uranus. Vera Marin

Adrian Bălteanu: Please comment briefly on the material published in the magazine "Arhitectura" no. 1/2011 regarding the Buzești-Uranus Diametral.

Vera Marin: I appreciate the strength of the images. It's important to put together images, data about the intervention and information about its progress. It is essential that people are informed so that they can react. I think that many people, even in the professional environment of architects or urban planners, have not formulated opinions about the Buzești-Berzei case, because they simply don't have enough information.

A.B.: You have publicly stated that the Buzești-Uranus project is not good, please tell me the main arguments in this respect.

V.M.: From my point of view we don't actually have a project. There was no urban planning. An urban planning project is an integrative gesture: in the framework content of a PUZ it is clearly written that the options are made after some analysis (baseline studies). There should also be a set of current urban principles and policies with the European ones, which through their filter integrate the project into the proposed study area. Filtered in this way, those options should be based on the results of some analysis: so there should not be in a PUZ a single perspective, a single theme - reducing the discussion to the theme of traffic flow leads us to a "PUZ for street widening" - a species that has no reason to exist in professional practice, especially when the initiator of this urban planning documentation is the local public authority itself, supposed to be the guarantor of a balanced development of the city.

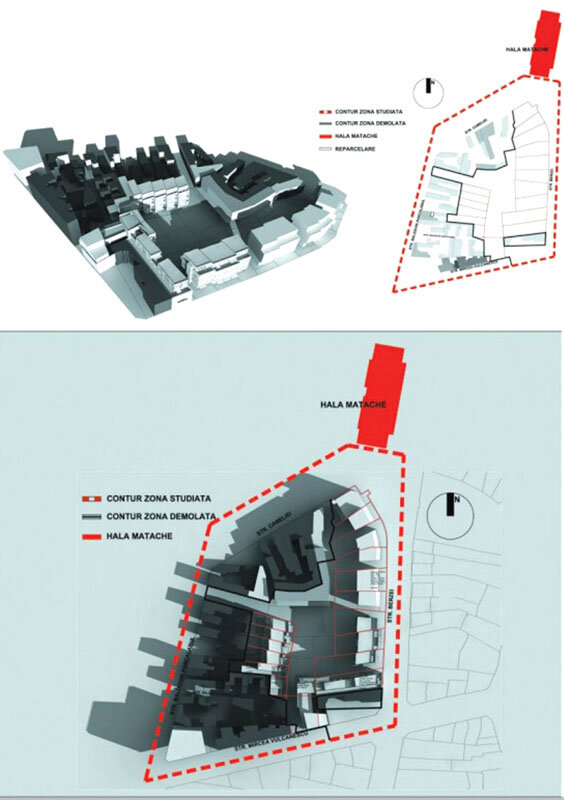

The current solution proposed by the city council, with those three-dimensional simulations that were shown at the Technical Commission for Urban Planning and in the presentations at the Sala Frescelor (UAUIM) and the OAR, is not realistic: that stylistic unity will never be achieved. Therefore, we have no image of what will be there. Apart from the fact that more and faster cars will pass through there, we have no projection about the future of that area. We don't even know how that area would function. Basically, we do not have that integrated urban planning project that I was talking about, but it is a 'legality' approach to cover expropriations, demolitions and some contracts signed with construction companies to work on widening that road. It is completely abnormal to carry out urban planning or urban design when the existing built environment has been massacred. We may find, after the finalization of the three PUZs initiated by the municipality at the end of last year, that those demolitions were not even necessary.

As a matter of principle, I believe that the starting point is wrong: that there is a need for fast movement in the area, in private cars, a transit movement between north and south, a fast link between the government building in Victory Square and the Parliament Palace respectively. The intervention runs counter to the principles of sustainable mobility promoted by professionals and assumed by decision-makers in the rest of Europe. A brief parenthesis. The decision-makers involved in this project should be aware that the Member States of the European Union signed the Toledo Declaration a year ago, which proposes the use of an assessment grid (the Sustainable Cities and Towns Benchmark), according to which an urban development can be checked to see whether or not it is sustainable. The grid is now in the testing phase, we even have three Romanian cities involved in the project - Bucharest, unfortunately, is not among them. The criteria used were not discovered overnight, they are the result of research projects. To close the parenthesis, for Buzești-Uranus, no one has bothered to discuss it in terms of sustainable urban development.

I have an idea that I want to go by car because I didn't have a car in the past and now I have one and I want to go anywhere with it, I repeat a reasoning of the project manager made public in a presentation at UAUIM. Also, the argument that is still being circulated by the authors is that the vision of a boulevard in that place has existed since the 1930s, but it was a time when cities did not have integrated urban principles and policies based on the experience of the last decades, and this meant that such projects could be proposed dictatorially by both the designer and the political factor. Today, this no longer has to happen just because, at the political level, we have signed documents in the European context that regulate differently the requirements of sustainable urban strategy.

A.B.: What do you think the area will look like if things don't change?

V.M.: If the current "project" is put into practice under the current conditions, we will have a street project, and the frontages will remain as they were after the war for a long time to come because, in my opinion, there is not enough financial strength with which to quickly realize the constructions to fill the frontages. And if let's say there will be investment, I have great doubts about the quality of the architecture of those fronts... Assuming that it will be built, certainly, not in five years, maybe in the next ten years, what will be built will be a continuation of what we see now on the segment of Buzești Street from Victoriei Square.

Unfortunately, the demolitions that happened on Berzei would only be the beginning - a dynamic will be set in motion that will bring radical changes to the protected areas neighboring this route. Much of the built heritage there is only of environmental value and is also in poor condition. This building stock will be replaced by buildings of the same type as those to be built on the Berzei, and the chances that the future of the area as a "protected area" will be in the direction of the character now existing there are greatly reduced.

Urban operations are the duty and privilege of public authorities. Choosing the perimeter of intervention, structuring the intervention through major decisions, phasing, budgeting, all these are specific activities of public authorities in connection with any urban project. Of course, the approach should not start from disparate project ideas, but urban projects are the way in which urban policies and programs are implemented, as part of a strategic planning approach. In other words, urban development projects or urban operations must be part of a broader approach to defining both the priorities and the possibilities available to the local public authority.

Local development strategy, public policies in the housing, green space and land use sectors, fiscal policies, public transport policies, public utilities accessibility policies, heritage protection policies, public space planning policies, etc. - all should contain programs and projects that need to be linked to each other. Intervening in a given perimeter means linking with the programs and projects defined in each of these urban policy sectors that have an impact on that perimeter. If urban policies and programmes are missing, urban planning operations that can be carried out in a public-private partnership will also be missing, since, in the absence of more general decisions already taken by the local public authority, there is no basis for legitimizing negotiations between the interests of urban actors (public, private, civil society) for a given individual project.

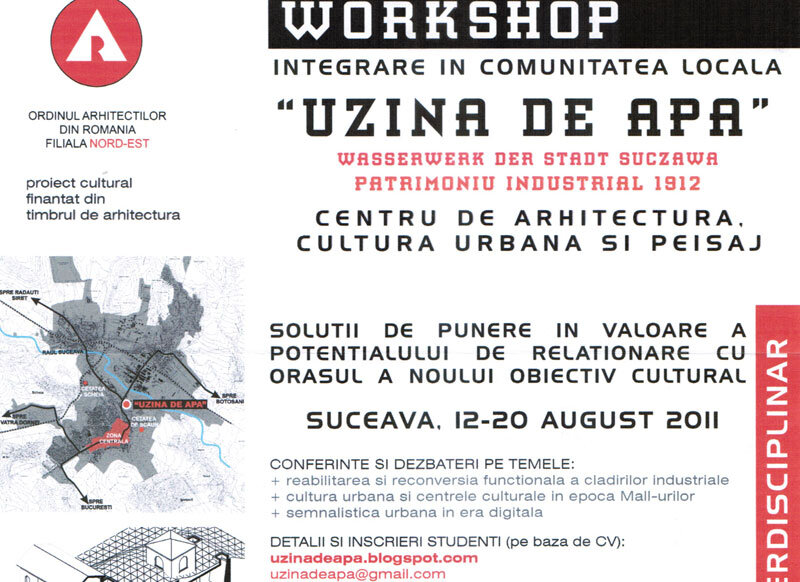

A.B.: What can be fixed? You have organized, with other specialists, an interdisciplinary Workshop to highlight that there are proposals as an alternative to this project for the area. Tell us a few words about the workshop.

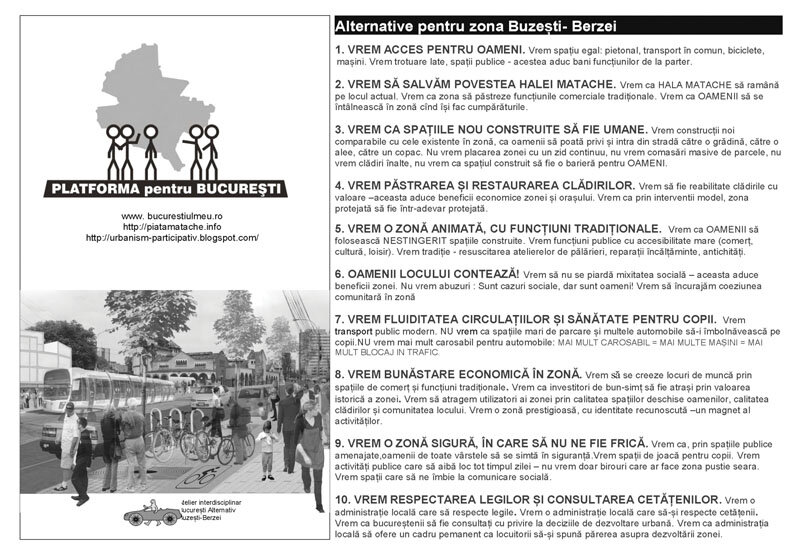

V.M.: I would have preferred not to have needed this Workshop. I would have liked to have been consulted in the process of elaboration of the PUZs commissioned by the local public authority, according to the methodological rules for informing and consulting citizens, launched, after many many years of delay, in January 2011. It is just that, together with the colleagues with whom I have joined, I have come to the conclusion that we cannot sit on our hands: I found the 'PUZ for street widening' far too unconvincing: I did not find any solid arguments for the proposals put forward there. I found the perimeter under discussion far too small. Worse still, the demolitions and the way in which they were carried out this winter were a deep disappointment. I was dismayed to see how far we are from Europe when I compared what was happening in the area with everything I had read on urban projects and with the places I had visited in other countries that were given as examples of public intervention in urban planning. I found that the attitude and gestures of several representatives of the Platform for Bucharest were perfectly justified. I can only welcome the fact that, in the meantime, the courts have already ruled in favour of civil society organizations in several lawsuits brought against Bucharest City Hall. I believe that complying with the procedures required by law is not unimportant. On the contrary: if the mayor does not comply with the law, what signal is he giving to the citizens of the city he administers? The law is not optional. And these procedures are not formalities: they impose filters through which a project must be judged - filters that should protect the public interest.

The workshop was organized by several non-governmental organizations, which have expertise and are also part of the active civil society: ASUB - Bucharest Urban Space Association, GDL - Group for Local Development, ATU - Association for Urban Transition and Anthropoesis Research and Development Centre. Often statements have been made that practically dissociate the professional environment from that of non-governmental organizations. I would like this workshop to be a first step towards a collaboration between the professional environment and the environment of those working for the protection of heritage or the environment, for example. I believe that we all have something to gain from such a collaboration in terms of legitimacy, in terms of getting closer to what is left to chance in Romania and Bucharest today: the public interest.

Through the workshop, we really wanted to bring together participants from the human sciences (sociology, anthropology) with those who come from the professional environment of planning and design, so with professional practice centered on space. We can no longer, in the 21st century, do urban planning only with those whose main training is related to space. The proposed urban form must be grounded in a functioning scenario, user profiles etc.

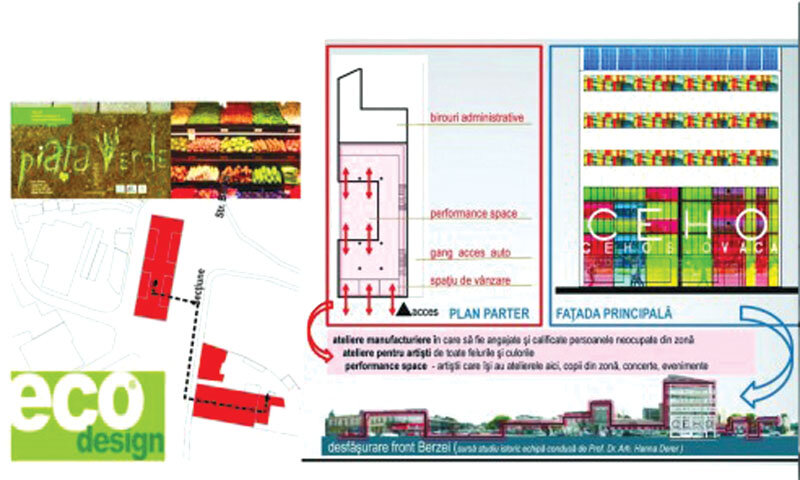

We put out a call for participation on the internet to which 50 applicants responded, from which we selected 25 with whom we formed six teams. We started by making some choices, the objectives of the workshop, namely that we had to discuss: sustainable mobility, heritage enhancement and economic and social development scenarios. The general objective was urban regeneration: to transform an area that is not much appreciated today, but which has remarkable potential, into a lively area, where there is energy, public space, buildings that respect the character of protected areas.

We also started from the principle that each team has to choose a site on this axis, or in the area bordering it, for which to make proposals that are not only about what that perimeter will look like, but also illustrate an operational approach for the implementation of the project (including identification of the necessary responsibilities for urban actors, costs, allocation of certain types of activities, etc.). Each team's project was intended as an opportunity to generate growth effects leading to the revitalization of the whole area.

We did not want to come up with a counter-proposal. What we set out to do was to open the discussion about the possibility of alternatives. Of course, if you change a fundamental premise: it is no longer a project for cars, but for pedestrians, you have an alternative. We wanted the intervention to be no longer at odds with European principles of sustainable urban development.

The workshop was organized without any funding, in the free time of those involved, so we physically did not have the possibility to come up with very elaborate technical details, which would have required collaboration with engineering experts etc. We also did not have the basic information about the legal status of the land. One can find 100 cross-sectional profiles for Berzei, but that is not what we set out to do, we set out to create the opening for the variant study.

We also set out to show that what is happening on Buzești-Berzei is symptomatic of the lack of urban planning instruments. It is the first public urban operation of this scale since 1990. We also want to make those interested in urban planning aware that the PUZ is not a sufficient tool for such an operation. For example, it's useless to give rules if I don't have the land assembly that will lead me to the desired urban composition. I write in the regulation that plots will be commingled, but what makes owners ever commingle their plots? I have no support in enforcing the rule. It is not enough to think about building rules, you also have to think about incentives, incentives, support measures on which the public-private partnership is based.

In other words, if interventions in the city are carried out on the basis of projects that are isolated from each other, then the question arises as to whether the decisions needed to start up and carry out an urban operation are correct: Why there? Why now? Why that measure and not another? Why with those private partners and not others? And if it is not possible to give answers to these questions with solid arguments that correspond to the elements that describe a project, then we cannot speak of a project for which the need has been clearly demonstrated and for which the course of action is the most cost-effective.

The North-South Diametral Twinning project is an illustrative example of the problems that can arise from an approach confined to a specific thematic sector of intervention: the widening of the Buzești-Berzei streets started from arguments of traffic flow. If we admit that the Transport Master Plan of 2008 is the urban policy on mobility in Bucharest and the metropolitan area, it would have been good if the decision to start this project had at least been correlated with the phasing recommendations contained in the Master Plan: first it was recommended to develop the public transport network and, respectively, to close the perimeter ring of the city. Street widenings in the central perimeter were not among the first projects listed in the action plan. In the absence of public policies in the field of heritage protection and in the context of insufficiently clear and strong regulations, it was not - not even for a moment - sufficiently clear, as a basis for decision, what the cost would be to be paid in order to be able to make these widenings in terms of identity values that would have to be sacrificed for the objective of traffic fluidization. Even worse, the streets in question are at the very limit of the area currently being studied under the PIDU - Integrated Urban Development Plan for the Central Area: the decision to intervene was taken before seeing the proposals of this integrated plan, which would certainly have given a clear hierarchy among the possible objectives for this area as part of the Central Area.

Following several decades of experience, Europe's cities see urban projects as precisely a vehicle for integration between the thematic sectors - these themes being as many areas of responsibility for local public authorities following decentralization: balanced development in the territory, accessibility for all categories of citizens to what can be achieved through investment from local, regional, national or European public funds: transport, housing, public spaces, green spaces, leisure, education, health, etc.

The objective of social cohesion (breaking down the spatial segregation of social classes) is an extremely important one in programs funded by national or European programs. In a European capital in the 21st century, it is unacceptable that there is no database of social cases in the area covered by an urban project. Just as the lack of a database of all property owners is unacceptable, not only for the plots directly affected by the street widening, but also for the entire area of influence of the project, which must be defined according to clear criteria.

Basically, if all that existed as a spatialization of this Diametrale project before it was put into action was a quasi-PUZ that only analyzed the widened route of the street, we are in fact talking about a lack of urban planning in the first urban operation after 1990. In order to put things on the track of a legitimate, fair public-private partnership, from which both the city as a whole and the private investors who might be interested stand to gain, it is extremely necessary that the right steps are taken, and that urban planning and design are taken seriously.