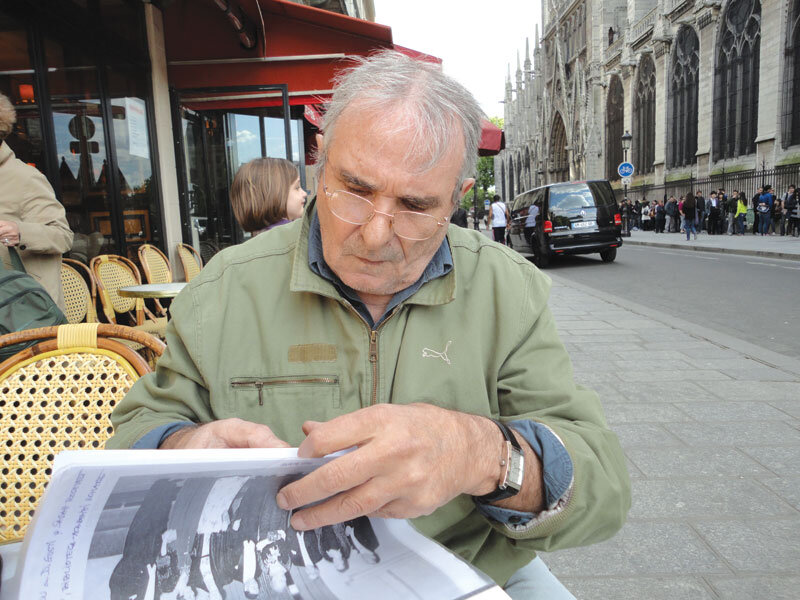

Annotated file Buzești - Berzei - Uranus. Hanna Derer

Adrian BĂLTETEANU interviews specialists involved in the documentation and elaboration of the studies in the project Doubling the North-South Buzești - Berzei - Uranus Diametral

Adrian Bălteanu: In the first issue of this year's magazine we had a "Silent Dossier" with photographs of the Buzești - Berzei area, less about the valuable buildings that have been lost or are in danger of being lost, and more about the atmosphere created by the construction site there. How would you comment on this dossier?

Hanna Derer: If I scroll through the visual or photographic memory of the images of this operation, I notice several things: the presence of cultural values that have remained isolated and therefore vulnerable, and a built heritage that is not always in a very poor physical state to justify replacement. We are often talking about ground-floor or ground-floor and one-storey buildings, but there are also some that have been removed even though they had larger floor areas. Under these circumstances, I wonder whether any study has taken into account the need to increase the built area in this area of Bucharest. In other words, does this need for housing and office buildings really exist? Finally, I ask myself, regardless of whether it is a public, private or public-private partnership investment, is all this effort, ultimately economic, to get rid of buildings that are still capable of standing for decades, justified? The answer may well be that the motive behind the whole operation was not the need for a larger built-up area, but to solve traffic problems. From this point of view, I confess, I find myself in a dilemma: on the one hand, the project manager himself, Prof. dr. dr. arh. Constantin Enache, publicly states that it is imperative to get from Victoriei Square to the Uranus area in 20 minutes by car, while on the other hand, he himself has also stated that the main reason for this urban operation was not traffic problems, but the need to create an area that would inspire security both for the inhabitants (who do not know to what extent they still live or will live here) and for investors. I can also accept the idea that both reasons were important, but I think that for such an effort and for such costs it would have been useful to have a calculation of the real need for the actual amount of built developed area.

A.B.: How do you assess where we are now in the realization of the doubling of the north-south diameter?

H.D.: From my point of view, the current situation on the ground, with the interventions carried out, has gone beyond the point where there would be a way back. The loss of the historic urban fabric is so great, and the work on the realization of the artery is so advanced that I find it hard to imagine that what has been destroyed could be restored, even if Romania were a much richer country than it is. I believe that, at the moment, we are dealing with three stakes, which I am mentioning in the order of the scale of place and in the chronological order in which they should be carried out, and not in order of importance, as I consider them to be practically equivalent in terms of significance. The first stake is the actual saving of those buildings of cultural value that still exist, the second is what will be built around them, and the third is to find ways to prevent such an operation from happening again. We don't want to face this kind of situation again, whether it's about saving the cultural resource or the way in which the north-south duplication of the north-south diameter has been implemented, both in terms of the design and the way in which the series of projects that are aimed at it have been realized.

A.B.: What are the main points of these three stakes?

H.D.: Of the buildings that need to be saved, the first on the list is certainly the Matache Hall, which has proved, following a study, that it is a historic monument, even of national interest, not just of local interest, as it is currently classified. The Hala, unfortunately, being not only 'attractive' from many points of view, but also large and not very easy, but not impossible, to supervise, is, as we can see, subject to permanent despoliation. What is extremely serious is that parts of the original metal structure, dating back to the end of the 19th century, from the first two stages of construction, have started to disappear. In addition to the hall, there are other buildings of cultural value, not necessarily in the front line of the doubling of the diameter, but mainly in the depths of the protected built-up areas crossed by the intervention or its impact zone - and not only historic monuments that have survived demolition thanks to the legal protection regime. These buildings located in the depths of protected built-up areas, even if they are still inhabited, are, in this urban void, just as vulnerable as those on the front line. This brings us to the second of the stakes. For the effective rescue and enhancement of both the isolated historic monuments remaining on the route and these buildings that contribute to the city's cultural resource, it is extremely important what is to surround them.

From this point of view, with regard to the built area proposed by prof. dr. dr. arh. Constantin Enache, from the latest plans that I had the opportunity to see in the public presentation of his Dominion (in February 2011), and I am therefore certain that I am looking at the most recent stage of the project, I understand that, in principle, a ground floor and six storeys in height is desired, which means more than a doubling of the built area that existed before the demolition operations. I can understand that for an artery with a generous prospect the frontages cannot have a low height regime, although there are appreciated examples such as Aviatorilor Road. Perhaps this would not have been the place for a promenading artery, as the Aviatorilor Road was certainly originally conceived, but for a dynamic traffic artery. Consequently, slightly higher frontages are needed in relation to the width of the street, but how high? Who defines this height and how? There were inter-war interventions in the area, P+3 - P+5, but such buildings were the exception. If I had to venture to say, at first glance, what the optimum height would be, I think that a P+3, with a ground floor for public use, and therefore higher, would be sufficient. In addition, this height scheme is perhaps more realistic in relation to the real need for built floor area.

Also, another fundamental aspect with regard to the future context of historic monuments and protected built-up areas is the pace at which the street frontage is developed. I refer again to the Aviatorilor Road, which indicates that an urban artery (disregarding its original promenade character) does not necessarily have to have a continuous frontage. A continuous frontage, even with more generous plots, nevertheless generates a relatively fast pace of reading, a rapid succession of images perceived along the route. In the area of the doubling of the diametral, through historical evolution, the frontages were formed by plots and therefore buildings with a facade length, not reduced, as in Leipzig, but medium. There is a fear that this type of frontage will be replaced by one made up of buildings with very long facades, which will change the rhythm of the frontages and will probably induce a feeling of monotony, as happens on Victoria Socialism, where, in addition, walking along, you have the feeling that you are not moving forward for the simple reason that all the facades look almost the same.

To avoid such situations, which are undesirable in Bucharest, there are, of course, tools available to the designer, who can limit the height and length of facades, and there are, at least in theory, tools that can be used by the landowner who is embroidering the route, in this case the city hall. It is not, I admit, clear to me what exactly the PMB has acquired, I have not had the opportunity to look at the plans in such detail and, in any case, I do not recall having had the opportunity to see a plan relating to the circulation of real estate. I have, however, seen instances where buildings have been half demolished, with the undemolished parts still in use, which leads me to believe that the city may have acquired strictly the space needed for the artery. In which case the question arises, "Where will the continuous G+6+6 frontages proposed by the developer be located?" or "what is the strategy for obtaining building plots along the artery, buildable under what conditions and by whom?". Hoping that these issues have been and are being taken into account, in which case the movement of land will be a clear operation, it is desirable not to produce an excessive height regime in relation to the average one specific to protected built-up areas, nor frontages with an extremely slow pace from one frontage to the next.

A.B.: Please say a few words about the heritage buildings directly affected by the doubling of the diameter, more specifically those that have to clear the site for its realization.

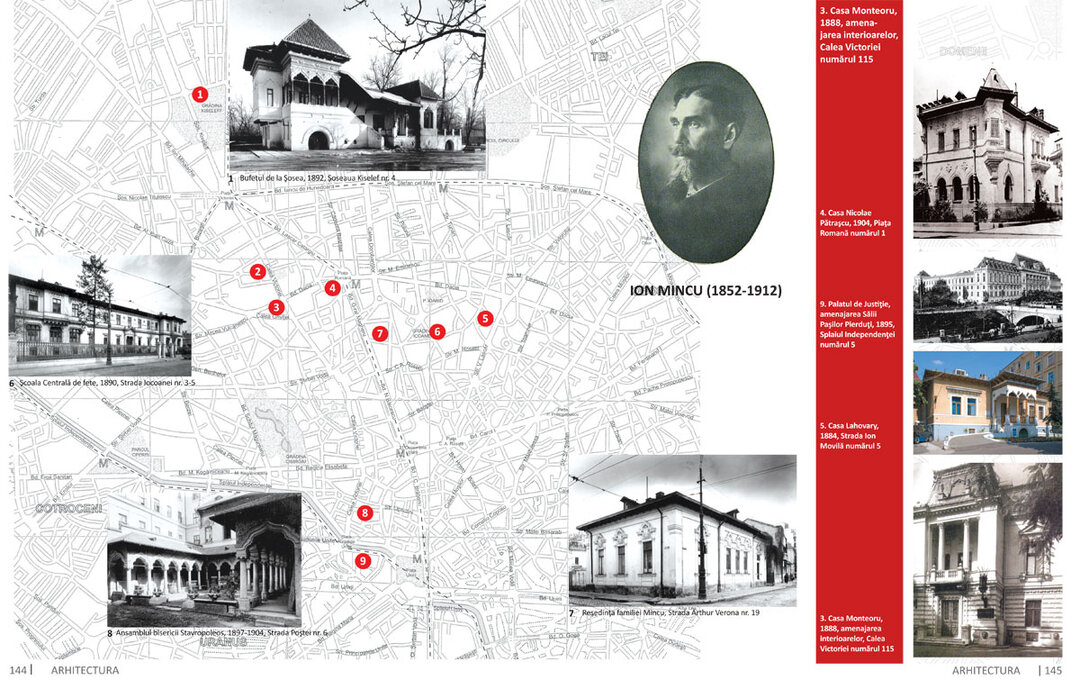

H.D.: At a first glance, one might think that, by pure chance, special buildings have appeared along the same street, a few hundred meters apart, over time. In the case of the three remaining historical monuments on Berzei Street (the Matache Hall has its postal address in Haralambie Botescu Square, but its main facade is part of the Berzei Street route), the research clearly shows that it was not a coincidence. Very briefly (the details and the demonstration are contained in an article that will appear in the next issue of "Revistei Monumentelor Istorici"), after the construction of the North Station, the town hall, aware that this part of the city could not remain one of vineyards and orchards, identified or intuited the commercial ford that had been standing since the first half of the 19th century at the intersection of Berzei and Popa Tatu streets and decided, in 1886, to give it a modern shape. Initially, this space must have been a 'maidan' in the original sense of the word (an unbuilt area used for commercial purposes, but not only.) The city did not therefore make a risky investment, because it was simply exploiting an existing commercial ford and because it was based on an unwritten public-private partnership, avant la lettre, in which the city and the community worked in unison. Proof of this are the other two historic monuments on Berzei, at number 89, about 250 meters south of Hala Matache, and at number 81, another 250 meters from number 89.

The building at 89 Berzei St. was, from the time it was built, a bakery, originally probably an exclusively or predominantly ground-floor building, which, in the Hale Matache's trena, was so successful that it acquired, very soon after the first stage of construction, not only a first floor but also a luxurious form. I am referring not only to the exterior architecture, preserved in situ until a few months ago, of which now, unfortunately, only a few fragments can unfortunately still be seen, but also to the interior architectural elements: door frames, stucco mirrors on the ceilings, etc.; in short, extremely rich architecture. I have never had the opportunity to see such a complex Neo-Baroque doorframe in Bucharest as the one here. It is obvious that only the bakery's financial success could have generated this kind of remodeling. The city hall's one-off initiative to build the Hala Matache attracted small entrepreneurs - like the one located at 89 Rue Berzei - who, capitalizing on the impact of the Hala Matache, have functionally enriched this part of the city. In return, such small entrepreneurs have returned some of the benefits to the area itself. This is also the case of the small bakery under discussion which occupied the vacant niche - it is known and supported by documents that its main function was the meat trade - which was floored and took on a representational architecture.

At number 81 is an equally interesting example of a joint venture, in which a freelance architect, Anton Schückerle - who, among other things, designed the Brewery and the Bragadiru Palace (and is therefore a successful architect) - decides to invest in the area, 12 years after the city council had initially invested in the hall and exactly the year in which it, realizing that the effort in question was worthwhile, completes it in accordance with the standard project. Anton Schückerle, who was then the owner of the plot of land at 81 Rue Berzei, draws up the design submitted for the building permit, proposing a building for the report. He senses that this part of the town will develop as a result of the investment made by the Hala Matache and entrusts his own investment to the area. What's more, Anton Schückerle is not only exploiting the area, he's giving it something in return: the resulting building may not be exactly luxury, but it's not one for raw real estate speculation either - the apartments are not only generous but comfortable, and the quality architecture, which I hope can still be seen on the site, is not to be mentioned. Like the little baker in 89 Rue Berzei, Anton Schückerle, taking advantage of the whole phenomenon of development in this part of the city generated by the intervention of the city hall, feels duty-bound to give something back to the area. That is why I say that this is a public-private partnership, avant la lettre, unwritten, but it worked very well, at a time when there was no public consultation in the current sense of the expression, but when I am convinced that the local authorities had other "antennae" to work with the population, to the benefit of both parties and, consequently, to the benefit of the city.

A.B.: What can you tell us about the other three monuments directly affected by the project, which are in the process of being downgraded?

H.D.: Two are (or were) located on Baldovin Pârcălabu Street, at number 16 and number 18, the third is (or was) located on Cameliei Street at number 24, at the intersection of these two traffic routes. In January-February 2011, when we elaborated the cultural evaluation studies, we found only minute traces of the cultural value that, with certainty, led to their inclusion in the List of Monuments

Monuments List in 1992. In Camellia Street, there is an obvious lack of maintenance of the buildings, which has caused an entire exterior architecture to disappear. I found a few fragments on the south façade of the building on the north side of the plot, but insufficient for any kind of integration/reconstitution/interpretation. The fragments testify to the neo-baroque style, of a different style than that of Berzei 89, somehow, if you like, more Transylvanian. On the body of the building located on the rear boundary of the plot, we found traces of window frames inspired by that variant of Central European Baroque known as

Zopfstil. Another significant aspect is the fact that, at the end of the 19th century, there was a building materials warehouse for sale on the site, whereas previously, in the middle of the same century, bricklayers, carpenters, and therefore craftsmen involved in building activity, lived there. In practice, this building was one of the elements that ensured the continuity of the functional profile of the area, thus making a major contribution to the cohesion of its cultural identity. Unfortunately, the fragments of cultural resources found were too few in number and, consequently, I had to propose declassification.

On Baldovin Pârcălabu, at numbers 16 and 18, we are talking less about lack of maintenance than about improper interventions: removal of the architecture of the facades facing the street, and possibly also of the interior architecture. From what I have been able to reconstruct mentally, the buildings were not initially exceptional, but interesting from various points of view. The building at number 18, for example, had a vertical circulation solution towards the attic and the rear of the building, which testifies to the desire for comfort in a building that was, after all, built with modest means. At number 16, we found in the basement an arch developed over the whole width of the house, over a very large opening for a typical dwelling, which merits archaeological investigation, which was also required at the end of the study. Given that the Borroczin plans of 1846 and 1852 show a building on the site of the present building, it is possible that the cellar dates from the first half of the 19th century and thus bears witness to an occupation of the land other than that typical of an area with vineyards and orchards. It is a significant urban presence and, crucially, a secular urban presence. Unfortunately, also in the case of this building, because the rest had been removed or mutilated by inappropriate interventions, except for the obligatory archaeological investigation, I had to propose declassification.

A.B.: Concerning the relationship between the doubling of the diametral and the protected built-up area, in your presentation a few months ago at the UAUIM, you pointed out that, according to the value analysis, the protected area should have extended much further west than the diametral, which means that the effects of the intervention are greater than those that would result from a first glance at its boundary.

H.D.: The gaps produced by this urban intervention in the urban fabric are to a large extent located on the current western boundary of the protected built-up areas, which became local law by the PUZ adopted in 2000. If we are talking about the preservation of cultural heritage, this legal limit does not correspond to the reality on the ground. Given the size and complexity of the city, the elaboration of the PUZ of Protected Built Zones was inevitably carried out in two stages. The first, completed in 1997, identified large portions of the urban fabric which, in one way or another, incorporated cultural resources. In some cases, all the components of the urban fabric (street grid, plot, built background, relationships between them, etc.) were culturally significant, in others only the street grid or the plot, etc., were significant. In the area of the present diametrical doubling, a number of protected built-up areas were identified, positioned transversely to it, the western boundary of which was, by the conclusions of the phase completed in 1997, indeed situated to the west of it. This conclusion also confirmed the results of the delimitation study of the historic center and the historic area of Bucharest, carried out 20 years earlier, which had used a different research method, also relevant for the preservation of cultural heritage. As early as 1977, therefore, it had already been noted that the cultural value crossed Berzei Street towards V, not, of course, the specific value of the historic center, but the value of the historic area, which, however, should be understood not as a zone of protection of the historic center, but as an area where the process of the cultural values was/is still in progress. Twenty years later, in 1997, it was therefore found that the historic area had indeed "grown" westwards, a sign of a natural evolution of the coagulation of cultural meanings.

The List of Historical Monuments is also in favor of what has been said so far. In 2006, when I had the opportunity to prepare the cultural resource baseline study for the doubling of the Diametrale, I compared the lists from 1992 and 2004 and found that the number of historical monuments of the building type had increased in this part of the city (while, for example, in Leipzig had decreased). In other words, the process of the cultural values' completion was in full progress and that part of the historic area (in the terms of the 1977 study) was on the way to reaching the status of a historic center.

In the second and legally final stage of the PUZ Protected Built-up Areas (adopted in 2000), the boundaries of the protected areas were restricted. Almost everything that crossed Buzești and Berzei Streets to the west in the first stage was withdrawn to the rear boundaries of the eastern lots bordering these streets. It should be noted that, at the same time, the General Urban Plan was being worked on and, as is well known, the idea of this new artery was (and is) included in this document. It can therefore be assumed that the 'withdrawal' of the boundaries to the E was the result of a negotiation between the team that drafted the second stage of the PUZ and the team working on the PUG. It should be emphasized that such negotiations are normally not only normal but desirable. Even the most inveterate specialists in the field of built heritage do not claim to keep absolutely everything. These negotiations are useful not only to decide the optimal balance between conservation and development, but also to clarify the reasons for one position or the other. I have had the opportunity to participate in such negotiations, invited as a drafter of the cultural resource study by the project manager, the town planner, and they can be beneficial for all parties involved, including, of course, the locality. In the case of the doubling of the diametral, I was not asked by the project manager to take part in a discussion. I don't know how the negotiation between the PUZ Protected Built Zones PUZ and the PUG took place, as the Department of Architectural History (of which I was a member) did not participate in the second phase of the PUZ. On the other hand, as far as I understand, there is no guaranteed gain for the city; the project manager of the doubling of the diametral, prof. dr. dr. arh. Constantin Enache, has stated that, for him, the stakes of doubling the Diametrale are to save the Via Victory, but that he cannot offer any guarantees in this regard. The profit of (real) negotiations is, when all parties involved understand what is to be gained in exchange for the losses, not so much a less vehement opposition to the project, but a global rethinking of the project; for example, the cultural heritage specialist, who understands the reasons and the gain for giving up some parts of the cultural resource, may take a different overall view, will look (in the same city) for similar urban structures and may condition those losses by an increased valorization of these other (similar) areas. I have not met a single cultural heritage specialist who wants to suffocate the city, for the simple reason that if the city becomes paralyzed, any ability to protect cultural heritage disappears.

A.B.: What can you tell us about the third stake you have identified, the non-repetition of such an intervention.

H.D.: As I said before, the third challenge is to identify ways to avoid in the future situations similar to the one related to the doubling of the Diametrale. From this point of view, a number of aspects need to be taken into account, where 'best practices' should perhaps be established. Thus, even if no one opposed a proposal contained in the PUG during the public consultation procedure for the PUG, when even a single supporting study for the PUZ reaches conclusions which do not support the operation in question, the aforementioned negotiations between the specialists concerned should be made compulsory. They should also present a single position to the beneficiary or, if this is not possible, the divergent points of view should be brought to the beneficiary's attention in extenso and in good time. Then, fundamentally, the decision-maker should take responsibility for the decision taken and, in addition, this should be made public. From this point of view, the formula of the technical opinions should also be reviewed, at least as regards those issued by the authorities empowered in this respect in the field of cultural heritage preservation. I say this because, at the moment, irrespective of the proposal made by the National Commission of Historical Monuments, the text of the opinion reads as follows: "The documentation was analyzed in the meeting of.... An opinion is issued...', without, therefore, the opinion of the commission being recorded in the document in question and, where appropriate, the fact that - given the consultative nature of the commission - someone else decided on the opinion issued. Last but not least, the consistency of the approval process should (however) be ensured, so that the Technical Committee for Urban Planning no longer gives its opinion in the absence of specialist opinions, such as that of the Ministry of Culture. Also, in the case of large-scale operations, a method should be applied whereby, at any point in the approval process, the complete and updated project as a whole is made available, and not just the various parts that are subject to approval at the time. There would also be a lot to say about the execution, at least as regards the execution consumed for the diametral doubling, but, as I do not know all the details, it is preferable not to comment. I am aware, however, that all these proposals mean more time is needed, which does not necessarily suit a political agenda, but, on the other hand, the quality of a locality cannot be achieved by short cuts. Finally, to return to the 'case study' of the diametral doubling, it would be interesting to find out how much the related processes cost the Bucharest taxpayer.

P.S. Incidentally, between the time when I had the opportunity to have this discussion (May 31 this year) and the time when I had the opportunity to review the transcript, the PUZ dedicated to the doubling of the N-S Diametral of Bucharest was declared illegal by the Bucharest Tribunal on April 12 and on June 16 by the Bucharest Court of Appeal.