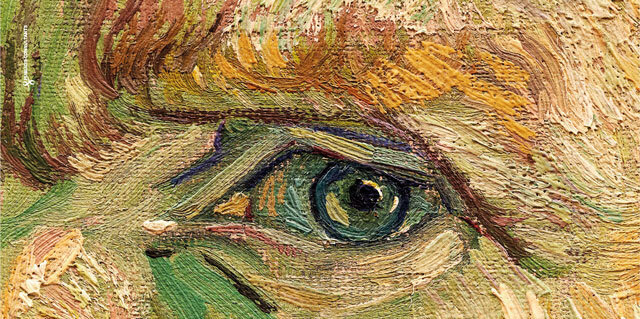

Historical monument and sacredness

The Summer University dedicated to the preservation of historical monuments, organized for several decades in Eger, Hungary, had a seductive theme in 1998: the "multicolored palette of historical heritage". One of that year's distinguished guests, Georgios Prokopiou, made a remarkable contribution entitled "Polychromy in Byzantine Art and Church Ornamentation" 1. After his presentation, reacting to a comment from the floor, the Athenian professor stated in a peremptory tone that for them, the Greeks, "every sliver of marble of the Parthenon is sacred".

Leaving aside the context - the decades-long restoration campaign of perhaps the most famous edifice of Greek classical antiquity was in full swing - the statement is sobering.

First, let us quickly establish that the word "sacred" here is to be understood metaphorically. Although the Parthenon was once sacred architecture, a temple dedicated to the city's patron goddess, by 1998, the cult of Athena Parthenos was no longer practiced by anyone. In other words, today's Parthenon, no longer dedicated to any religious cult, cannot be considered sacred architecture.

This could not be ignored by the man who had just given a lecture on the Byzantine art of Christian churches. The sacredness of the marble fragments from the Parthenon had, and still has, a completely different meaning, rooted in the very complicated mix of values, representations and functions associated with historical monuments. In this sense, we can speak metaphorically of the 'sacredness' of the fragments or component parts of the built heritage, even when it cannot be a question of sacrality in the strict sense of the word, associated with a religious cult.

When, for example in the case of Byzantine Christian churches classified as historical monuments, the religious cult to which the building was originally consecrated is still practiced within its walls today, the sacred character generated by the temple function is intact. This is irrespective of the extent to which the component parts of its mosaics are or are not considered 'sacred' by members of the restricted or wider community who share the values associated with historic monuments, are reflected in their representations and participate in their identity function2.

We can already conclude that there are two distinct registers of architectural sacredness: one in which the sacred character derived from the cult function of an edifice and conditioned by the ritual gesture of consecration is inscribed; the other in which the physical substance of an ancient artifact, identified by a community as having accumulated values specific to a historic monument, is valued as the bearer of these values. The (essentially secular) reverence with which societies regard the historical monuments they recognize as such may confer a kind of 'sacred' character on them.

Secondly, it should be noted that this is not a play on words, but an attempt to decipher architectural meanings with immediate practical effects. To fail to make the essential distinction between the literal and the metaphorical meaning of the architectural sacred in the two cases can lead to errors of judgment when the question of the conservation and restoration of a historic monument is at issue. It is so, and not otherwise: whenever it is damaged or lost (through desecration or just banal construction work), the sacredness of a religious edifice can be fully restored by performing the canonical rite of consecration. On the contrary, no premeditated human gesture will ever be able to restore the 'sacredness' - or authenticity - of a historic monument, diminished or destroyed by inappropriate intervention.

Perhaps this is the key to the fascination of historic monuments. Beyond their specific values, every artifact in this category exudes a sense of uniqueness, a sense that its disappearance would be an irretrievable loss.

These buildings, cherished as the keepers of the memory of modern societies, form a corpus whose scope continues to expand as more and more diverse - and more recent - categories of artifacts are added. "First 'discovered' by Renaissance humanists in the substance of the remains of Greco-Roman antiquity, historical monuments tend to associate, with the passage of time, any building whose stylistic or constructive features place it in a relative past. However close, the past is part of the essence of historical monuments: it takes the passage of time for the collective memory to fix on an artifact and to want to preserve it. There are always reminders of times that recede from the present with each passing second.

Read the full text in issue 2/2012 of Arhitectura magazine.

Notes:

1."The Polychromy in Byzantine Art and Church Decoration - Origin, Form and Technique", in Acts of the 28th Summer University

on Monument Protection, Eger, June 30-July 8, 1998, OMVH, Budapest, 1998, pp. 169-178

2. See Françoise Choay, Alegoria Patrimoniului, Simetria, Bucharest, 1998, especially p.132-133 and Kázmér Kovács, Timpul monumentului istoric, Paideia, Bucharest, 2003, especially p. 43-44.