Living heritage. Why do we bother with (our) monuments?

Monuments torment people, and people torment monuments. We are talking about the Romanian people here, even if other peoples are perhaps experiencing the same dilemma.1 In the collective precept, which has become a law, the monument is an exceptional cultural asset, valuable for the documentary testimony it conveys, hence the obligation to preserve and conserve it.

In order to achieve this goal of saving and conserving it, a professional ecosystem has been created from which there is no shortage of specialists, experts and other specialists and experts, all of whom are divided into clearly defined professional competences and attested by a series of procedures, which are guarantees of professional excellence (in the established field only).

In various projects2 we have witnessed very special associations: the encounter between the ecosystem described above, plus the administration, the monument and the monument owner, an encounter - one might say - almost scandalous, unforeseen and contrary to nature; the relationship between the certified staff, the well-meaning owner and the innocent monument has tragic aspects. The situation becomes even more complicated when, as is very often the case in the Banat area, we are dealing with a Gründerzeitbebauung type of built environment, based on the idea of a cultivated coexistence of the citizens of the town and their ability to manage a common property. At the moment

When the three variables - specialist/owner/monument - are linked, confusions with distant origins begin to take effect. The specialist often comes well equipped with notions that the owner does not understand. The owner, for his part, tormented by the monument in which he has to bring up his children, pay the bills, care for the elderly, often comes with a clear vision of what needs to be done, how it should be done and how much it should cost. On top of that, the administration comes up with a coercive law that doesn't help anyone, and the monument is already there and has been waiting for a long time. The problem for many owners is that they only wanted an apartment, not a monument.

Of course, why they didn't inform themselves at the time of purchase, one may retort, but the fact that the rehabilitation of historic buildings3 does not happen in empty houses should also be of interest because the success and sustainability of the rehabilitation depends to a large extent on that owner, or those owners, and the way in which the special property is understood from the possession.

Unfortunately, at present, absolutely nobody is coming to the aid of these owners.

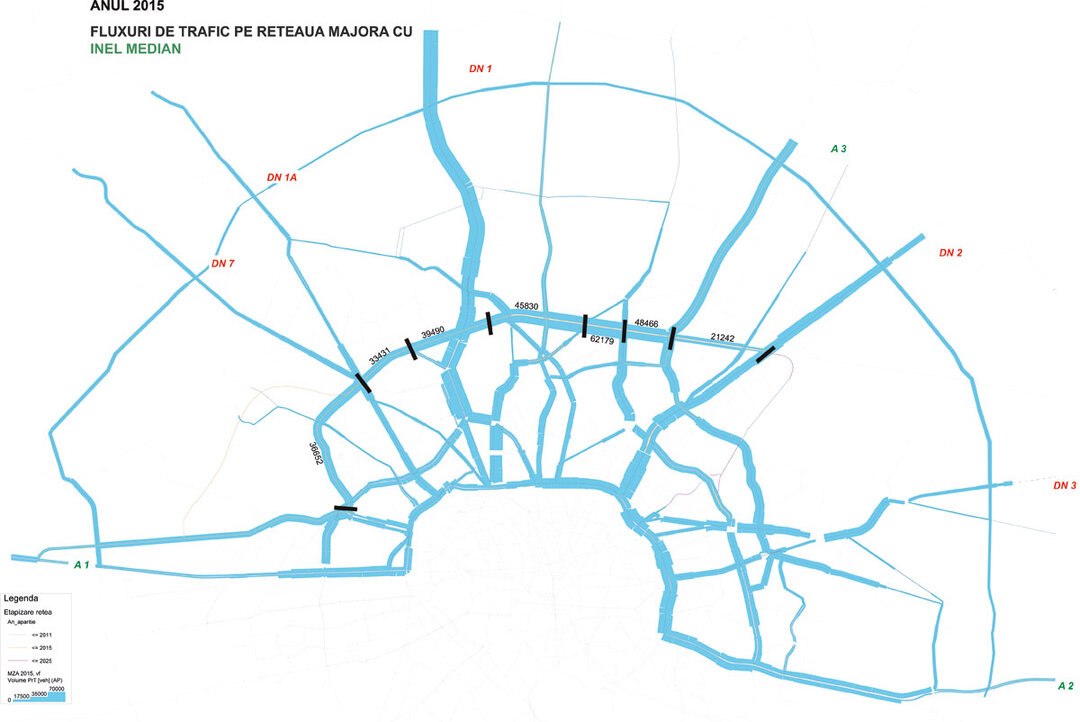

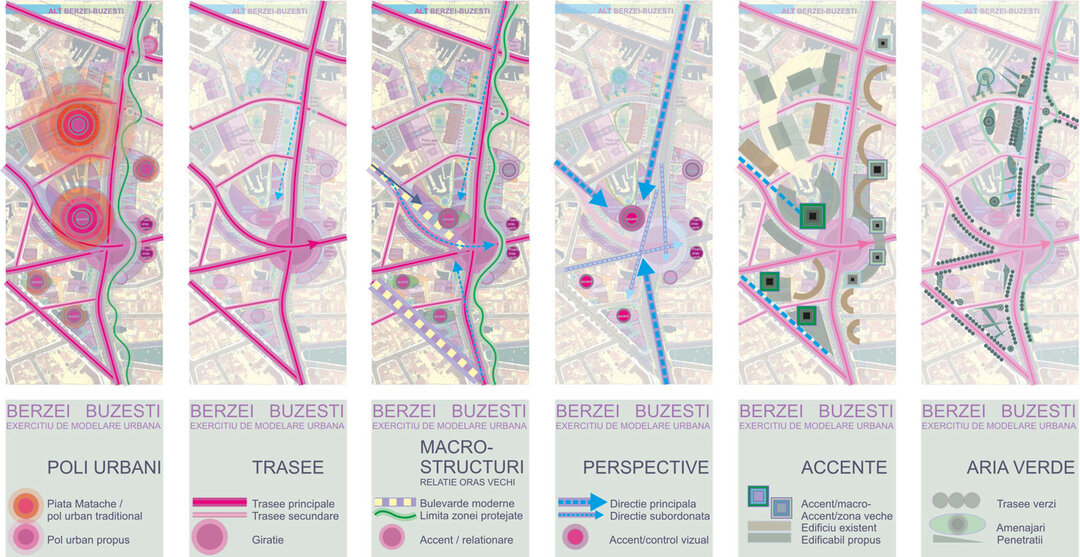

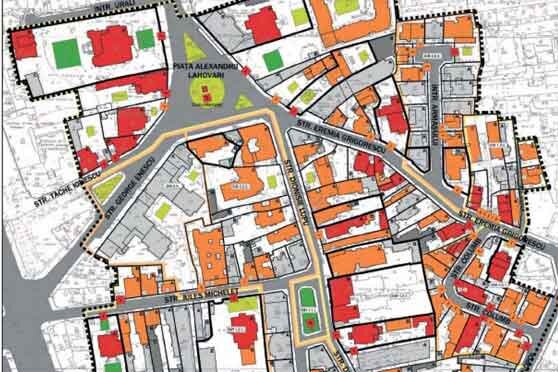

Another confusion: when we talk about monuments, we invariably imagine singular buildings, of major importance for national or local identity, which need to be restored and preserved over a long period of time. But a large proportion of monuments are in fact dwelling houses, forming neighborhoods rather than just ensembles or not just part of sites. Their importance lies not only in their status as historic areas, but also in their urban character given by the structure of the public space and a functional mix motivated by historical evolution and density. The rehabilitation of such areas cannot be approached exclusively from the point of view of the physical rehabilitation of buildings, monuments or ensembles. If the rehabilitation programme is not part of a comprehensive project for the revitalization of the historic area, with components of investment in the public space, public awareness, direct professional advice, non-invasive measures to improve infrastructure4 and economic development of the area concerned, it will have a reduced sustainability.

Our system unfortunately leaves room for many interpretations. Who is responsible for the historic building, a monument? A ministry, the local community, the owner or the expert specialist? And hence the most burning question, who finances the rehabilitation works of a monument? Apparently, the Romanian state has understood the need to preserve the built heritage, and there is a law to this effect. However, it is a law which does not produce the desired effects, which has no support in the legislative framework as a whole and, worst of all, which is not accompanied by funding programs not only for state-owned buildings (in one form or another), but also for the owner as a private person5. This type of financial support has been and is possible in Romania only under the conditions of attracting external funds or as a measure imposed and applied directly by the Romanian state on certain properties, with the owner's consent6. The social unsustainability of such a measure is obvious, given that the owner's entire contribution is his agreement to the rehabilitation. What can Romanian citizens learn from this? He can learn that the state will come periodically, every quarter of a century, to fix the "facade"7. Unless we find a system in which the responsibility for rehabilitation and its financing is shared equitably between the owner and the state, we will not have a lasting solution to the problem.

The practice that, for listed buildings, the responsibility for decisions lies with the Directorates for Culture has also led, over the years, to a total erosion of the local administrations' identification with the historic built heritage, which has been assimilated to the idea of monument, ensemble, site, which is neither correct nor efficient from the perspective of ensuring a living future for historic districts and, by implication, the monuments, ensembles or sites that are part of them. Some administrations8 have tried or are trying different models for financing the rehabilitation process.

Unfortunately, the only successful ones have been those financed by foreign states, in particular Germany, through GTZ, in Sibiu and Timișoara9. This is inadmissible, in fact, as the monuments in question are on the National List of Monuments, even if they are privately owned.

At present, Timisoara is the only city in Romania that implements a financial support program for private owners in historic districts, the main components of which are the granting of subsidized interest loans through the local administration and the provision of technical assistance for design, execution and site management by local and foreign architects/engineers.

But this is only possible because the municipality in turn obtained a grant from KfW10, a German state bank. It is not the details of the program that are of interest now, but the fact that this program is a special case and impossible to replicate in Romania without a major legislative change, with the aim of obtaining mechanisms through which the state, with public money, can subsidize or support the rehabilitation of buildings that it itself has accepted and declared to be of public importance11. Otherwise, the financial responsibility for the rehabilitation of a vast built stock inhabited by a socially and financially heterogeneous population will continue to be assigned exclusively to owners who currently feel no pride in living in the center or in a historic area, gathered in non-functional owners' associations, and this situation will not be remedied in any way in the foreseeable future. This does not, however, in any way mean that we should once again be gripped by pre-decembrist reflexes. It is not the concessioning of facades, not forcible rehabilitation, not (only) fines that are the most effective or appropriate instruments. An intelligent state knows better than to apply the force at its disposal. Nor is 100% subsidization, as applied for the rehabilitation of the facades of Sibiu through the Ministry of Culture, a solution with lasting effects12. The experiences of others have shown that the rehabilitation effort should certainly be supported by the administration, but in such a way as not to undermine the owner's responsibility, because private property in the form of a historic building or monument is always, to a greater or lesser extent, also of public interest and should be treated as such.

The model offered by the project financed by KfW in Timișoara and carried out by the local administration there provides a good start for an approach that would make it possible, at national level, to implement such financial support programs for private owners, which would also include technical assistance during the design and execution phase, in order to guarantee a prudent and technically correct rehabilitation, in relation to both the needs of the inhabitants (comfort and quality of living) and the historical value of the object. In turn, such a programme should be integrated into a broader concept of revitalization of historic districts13 , which should lead to the economic, social and cultural regeneration of historic areas, of which the physical rehabilitation of buildings is only one part.

Notes:

1 In Germany there is currently a dispute about the role of monument commissions. They are becoming instruments of discreet advice and persuasion rather than advisory and control commissions. Silke Gronwald, Stern: Aufbau Rost, 23.04.2003

2. Romanian-German cooperation project "Prudent Rehabilitation and Economic Revitalization of Timisoara" between the Municipality of Timisoara (PMT) and the German Society for Technical Cooperation (GTZ. Now GIZ)

3. I will use this term instead of monument, given its wider range of meanings

4. The case of infrastructure modernizations for the relization of Bd. Uranus in Bucharest does not fall into this category

5. Nor are they possible under the current system, given the impossibility of spending public money on privately owned buildings. Richard Haimann, Die Welt: Finanzamt belohnt wohnent wohnen im Denkmal, 30.05.2009

6. http://arhiva. cultura.ro/News.aspx?ID=604, press release of the Commissioner of the program "Sibiu - European Capital of Culture 2OO7", SIBIU, 08.08.2005

7. We are not discussing the partial nature of the rehabilitation measures in relation to the fundamental problems of the buildings in question

8. Timișoara, Oradea, Sibiu etc.

9. I refer to programs for the revitalization of some historical centers, which also had a component of rehabilitation of the inhabited buildings.

10. http://www.cdep.ro/pls/legis/legis_pck.htp_act?ida=100390; program run by the Municipality of Timișoara and funded by KfW. The technical assistance is provided by SPS Plan Leipzig, sc Vitamin Architects srl, at the request of the public administration and contracted directly by the donor

11. At least as important as the rehabilitation of monuments is the revitalization of historic areas in the form of functional districts important for the identity and economic competitiveness of Romanian cities. Smaller cities in particular can benefit significantly from a properly and functionally rehabilitated historic center

12. The effect of such subsidization is to perpetuate the expectation expressed by many owners that the administration will intervene on their buildings. Intuitively, I would say that in most cases those who have such expectations are those who bought under Law 122, which de facto amounted to a legalization of nationalization without any action program to ensure good management of these buildings. The setting up of owners' associations, for example, was not compulsory before the sale, as was the case in Leipzig, also after 1989

13. See the Integrated Concept of Measures for the Rehabilitation of the Historic Districts of Timișoara or the future INTEGRATED PLAN FOR THE REVITALIZATION OF THE PROTECTED ZONE OF ARAD